Influencing Government: Food Lobbies and lobbyists

advertisement

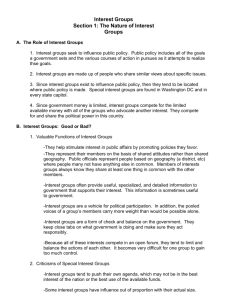

From Food Politics: How the Industry Influences Nutrition and Health Marion Nestle To understand how food companies are able to exert disproportionate influence on government agricultural and nutritional policy Any legal attempt by individuals or groups to influence government policy or action Promoting views of special-interest groups Attempting to influence government laws, rules or policies that might affect those groups Communicating with government officials or their representatives about laws, rules, or policies of interest Provide federal officials with well-researched technical advice about proposed legislation, regulation, and public education. Establish personal contacts through meetings and social occasions Arrange campaign contributions Stage media events Organize public demonstrations Harass critics Encourage lawsuits 1787—James Madison concerned about “mischiefs” caused by special-interest groups 1911—lobbying made legal. Lobbyists must register and disclose sources of funds. BUT Unenforceable 1995 –lobbyists defined as people who spend at least 20% of their time lobbying, have contact with government officials or staff, and are paid more than $5,000 in a six month period for this work. BUT all three criteria had to be met In 1995, House rules: barred lobbyists from buying meals for members or aides (with an exception) small gift items still acceptable. Senate rules: cannot accept paid travel to recreational events or gifts and meals worth more than $100 from any one individual in a year In 1998, an estimated $1.42 billion spent on lobbying… Each of the 100 senators and 435 representatives contacted by 38 paid lobbyists spending $2.7 million on each legislator to do so. After WWII food producers, USDA officials and members of the House and Senate Agricultural Committees closely united 1970s—system begins to break down as new constituencies demanded influence Consumers Large processing and marketing companies Advocates for the poor In 1970s Congress expanded jurisdiction of agricultural committees Not only: agricultural production, marketing, research and development But also: rural development, forestry, domestic food assistance, aspects of foreign trade, international relations, market regulation, taxes, and nutrition advice to public. Resulted in huge upswing in lobbying activities 1950s—25 groups of food producers dominate agricultural lobbying Mid-1980s –84 groups Late-1990s—1000s of groups, including businesses, associations, law firms, and individuals Frequent job exchanges between lobbyists and federal officials (revolving door) Transfer of funds from lobbyists to federal officials through donations of ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ money as well as gifts Job exchanges between lobbyists and USDA, FDA common The curious case of Mr. Taylor Presents dilemma: Valuable expertise or conflict of interest? “Hard Money” Governed by legislation (Election Campaign Act) Limits amount of individual contribution to $1000 and PACs to $5000 Does not restrict number of candidates, nor number of PACs to which individuals may contribute Political Action Committees (PACs) Collect “voluntary” contributions from members for donation to political campaigns Most do not contribute equally to parties (Republicans receive more) Funds go where they will benefit the donors (House and Senate Agriculture committees) “Soft Money” Election Campaign Act only restricts contributions for federal elections, neglecting to mention state and national political organizations. This loophole allows contributions to support campaigns indirectly, come from any source, be in any amount, and do not need to be disclosed. In the ‘97/98 election cycle agribusiness corporations made soft-money donations of $1.3 million to Democrats and $1.4 million to Republicans Research suggests a strong correlation between contributions and desired outcomes Case study: Sugar Largest contributions from sugar PACs went to members who voted for subsidies; the larger the PAC contribution, the more likely members were to support industry positions In 1991 42% of sugar subsidies went to 1% of growers Fanjul Family Controls 1/3 of Florida’s sugar-cane production Collects $60 million annually in subsidies Contributed more than $350,000 to political parties in ‘97/98 Political Influence: As seen in the Starr Report The job of food lobbyists: Ensure that the government does nothing to impede clients from selling more of their products Do as much as possible to create a supportive sales environment