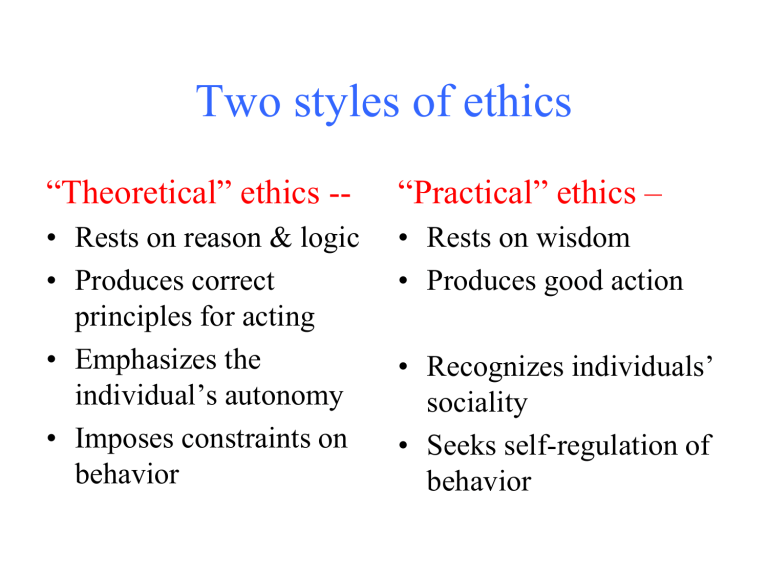

Two styles of ethics

Two styles of ethics

“Theoretical” ethics --

• Rests on reason & logic

• Produces correct principles for acting

• Emphasizes the individual’s autonomy

• Imposes constraints on behavior

“Practical” ethics –

• Rests on wisdom

• Produces good action

• Recognizes individuals’ sociality

• Seeks self-regulation of behavior

“Theoretical” ethics

For example, Kant --

• Find correct maxims for behavior

• Accomplished by applying a logical test – the “rational” conceivability (reversibility and universalizability) of the maxim

• Done in “splendid” isolation

• Constrains us to act in ways we ordinarily might not, e.g., against our self-interest

“Theoretical” ethics

For example, Utilitarianism --

• Find correct action in a particular situation

• Accomplished by making a rational calculation – the best balance of benefits vs. costs (understood broadly to involve more than actual dollars)

• Done in “splendid” isolation

• Constrains us to act in ways we ordinarily might not, e.g., against our self-interest

Simple example

“Theoretical” ethics –

• Drive below posted maximum speed

• Drive above posted minimum speed, if any

• Observe variable speed zones

• Etc.

“Practical” ethics –

• “Drive at a speed reasonable and proper”

Less simple example

Old Testament Ethics

• Do the things on this list

• Don’t do the things on this other list

• Do what it says in that big stack of books

New Testament Ethics

• “Love the Lord your God with all your heart…soul…strength… and mind, and love your neighbor as yourself”

(Luke 10:27)

Aspects of “practical” ethics --

Community

• Our reality is essentially social – individuals exist only in communities, and communities themselves are built of other communities

• Our well-being is dependent on the wellbeing of the interlocking communities of which we are a part – including the businesses for which we work

Aspects of “practical” ethics --

Excellence

• Being “ethical” is acting “virtuously”

• Virtue (or being virtuous) is a matter of actively seeking excellence in our lived reality, rather than passively adhering to imposed standards

Aspects of “practical” ethics –

Role Identity

• Ethics is contextual, in the sense that at every moment and in every ethical decision we have multiple sets of roles and responsibilities within our intersecting communities

• Simple, absolute principles will always miss the ethical mark

Aspects of “practical” ethics --

Integrity

• The situational character of our ethical decisions means that different virtues will take precedence in different cases

• Integrity thus becomes the “linchpin” virtue

Aspects of “practical” ethics --

Judgment

• A mechanical application of simple rules will not work

• Broad judgment, wisdom, “moral imagination” is necessary

Aspects of “practical” ethics --

Holism

• Just as we must ethically integrate ourselves into our communities, we must integrate ourselves.

• Good character yielding “naturally” good behavior, rather than disjoint, piecemeal ethics

For example, Aristotle’s

“practical” ethics

• Virtues are a balance point between two extremes

– for example, courage lies between cowardice and foolhardiness

• The particular balance point depends on us and our individual situations, and our judgment enables us to determine what it is

• We ingrain a virtue and help make it “second nature” every time we act virtuously – for example, we become courageous by acting courageously

Being ethical Aristotle’s way

• Adopt the ideals for behavior that are embodied in the virtues – honesty, loyalty, courage, benevolence, civility, tolerance, wit, magnanimity, etc.

• Develop good character by practicing these virtues.

• Use the wisdom you have gained from this practice to “blend” the virtues appropriately for the differing situations of your life.

• Virtuous action will then flow from you as your second nature