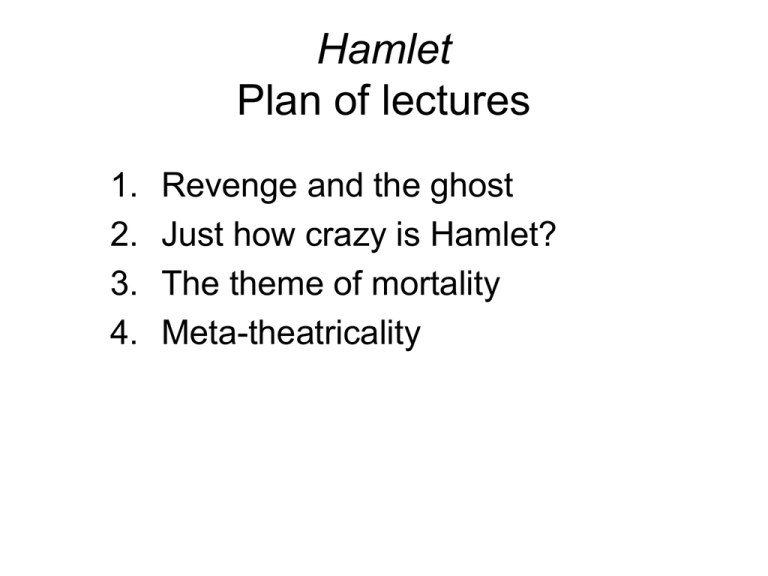

Hamlet Plan of lectures

advertisement

Hamlet Plan of lectures 1. 2. 3. 4. Revenge and the ghost Just how crazy is Hamlet? The theme of mortality Meta-theatricality Preliminaries: first, the strange text of Hamlet • Our edition (Pelican), edited from the second quarto (Q2), is approximately 3,674 lines long. • Far too long to play (four hours if played). (Elizabethan plays took two to two and a half hours to play.) • Probably Q2 is Shakespeare’s early draft of the play. • The Folio version (F) is 3,535 lines long, still far to long to play. • Probably F is a revised version of the play; it lacks much of IV.4, including H’s soliloquy there. • Some scholars think F is a clearer version of the play, suggesting revision. • The first quarto (Q1) is much shorter, 2,154, and looks like a playing version of the play. • Some scenes are in a different (maybe better) order. • But Q1 gives us a weird version of the text, certainly not Shakespeare’s actual language. • Q1 derives from an actor’s version of the play from memory – only Marcellus’ lines are accurate. The puzzling text (continued) • So a modern production needs to decide which text, Q2 or F, to use, then how to cut about a third of the text. • Earlier editions gave us a Hamlet that was conflated from Q2 and F – an even longer play. • Branagh’s film of the “uncut Hamlet” is interesting, but something that was almost certainly never played in Shakespeare’s time. • But what was played? • What we’re reading in the Pelican text is probably Shakespeare’s early complete draft. • Which he had to cut for playing. • Look for extra F passages on pp. li-lv of Pelican if you’re missing some familiar passages. Second, five “open questions” in Hamlet • Is Hamlet mad or not? He says he will play mad (put on an “antic disposition,” 1.5.171-72), but then later tells Laertes that it was his “madness” that killed Polonius, not Hamlet (5.2.231-240). • Does Gertrude know about the murder of Hamlet’s father? Hamlet thinks she does, but she seems shocked at his accusation (3.4.29-31). • Did Ophelia really commit suicide? Gertrude’s account indicates it was an accident (4.7.166-184). The coroner rules it “Christian burial.” But the gravediggers have their doubts (5.1.1-30), and the priest says the death was “doubtful,” and the funeral rites are truncated (5.1.228236). • Why did she go mad? The death of her father? Or Hamlet’s rejection of her? • Does the “play-within-the-play” evoke Claudius’ guilt? Or is it Hamlet’s commentary (3.2.267-70). Third, R.I. P. “tragic flaw” • Aristotle invented the tragic flaw: hamartia. • But was it part of current discourse in 1590s? • Here’s what Olivier did with tragic flaw in his 1948 film (clip). • Admittedly Shakespeare seems to bring up the issue at I, 4, 23ff. • But how much does “tragic flaw” ever tell us? Othello is jealous, Macbeth is ambitious, Lear is old and losing his mind, Romeo loves too rashly? • And Hamlet does make up his mind at III, 3, 73ff – maybe that’s the problem. Now, the lecture: that damned ghost – or is he? • Hamlet a revenge play, a popular dramatic genre. • Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy (1592), Marston’s Antonio’s Revenge (1600), Middleton’s Revenger’s Tragedy (p. 1607), Chapman’s Bussy D’Ambois (1604), Shakespeare’s own earlyTitus Andronicus (p. 1594). • Elements of revenge plays: ghost demanding vengeance, real or feigned madness, playswithin-plays, scenes of carnage and mutilation, ingenious ways to accomplish vengeance. Hamlet as revenge play • Horatio’s conclusion: V, 2, 380-87: “So shall you hear of carnal, bloody, and unnatural acts . . .” • But atypical in its psychological complexity – and length. • Ghost kept off stage for four scenes – a half hour of playing time? • Issue of revenge kept in suspense. • The strange character of this ghost: where from? What to make of him? Film clip of ghost’s appearance The ghost of Hamlet Sr. • The ghost is real: on stage this must be a very solid, opaque ghost, no see-though or imaginary figure. • Is the ghost from Purgatory? • Purgatory a hot-button issue in Elizabethan England. • Ghost asserts Purgatory as its origin: I.5, 3-4, 913. • This puts it among the saved, “a spirit of health,” as H. says (I, 4, 40). • But can it then ask for vengeance? If the ghost simply wants justice. . . • . . . how should it ask for vengeance? • Can Hamlet be simply an instrument of God’s justice? • If he can, how should the crime and the punishment be presented? • At the end of the speech: “But howsomever thou pursues this act,/ Taint not thy mind, nor let thy soul contrive/ Against thy mother aught. Leave her to heaven/ And to those thorns that in her bosom lodge/ To prick and sting her.” (I, 5, 84-88). • Hamlet must become like the executioner, who is disengaged from the act of taking life. But the rhetoric of the ghost’s speech cuts against this: • • • • • The horror of his “prison house”: I, 5, 12ff. Rhetoric of bitterness: I, 5, 42ff. Rhetoric of betrayal. Highly physiological description of crime. Everything in the speech seems designed to elicit an extreme emotional reaction from Hamlet. • Line 80: “O, horrible, O horrible, most horrible!” • Then the strange coda: don’t taint your mind or harm your mother. Can one take a life without tainting his mind? • • • • • The public executioner. Anonymous, hooded. Asked forgiveness of his “client.” Acted simply on behalf of the state. Maintained his own disinvolvement with the act of taking life. • Can Hamlet attain this state of moral neutrality? The nature of the ghost’s charge to Hamlet • Kill your uncle, your father’s cold-blooded killer . . . • . . . who led your mother to adulterous betrayal of your father . . . • . . . who killed me in a particularly horrible way . . . • . . . and left your father no time for a proper death (confession, communion) . . . • BUT don’t taint your mind, or harm your mother (while killing her current husband). • Can any of this be done? The effect on Hamlet? • His invocation of heaven and earth (I.5.92ff) – and what else, hell? “Oh fie!” seems to reject hell. • He’ll forget everything except the ghost’s command. • Is Hamlet a bit mad when he rejoins his companions? • Horatio: “These are but wild and whirling words, my lord.” • Hamlet driven to extremity by the ghost? Hamlet tests the ghost • II.2.537ff. Admits the ghost may be a devil sent to trick him to damnation. • So “the play’s the thing/ Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the king!” • The “Mousetrap” indeed appears to catch the king’s conscience. • Horatio seems to agree that Claudius’s guilt is apparent. • Having tested the ghost, Hamlet now morally bound to act? • But see the divided rhetoric of III, 2, 381ff. “I will speak daggers, but use none.” The scene that indicates Hamlet’s seeming readiness to act • The time and place of III, 3, 36ff: Claudius appears to be praying. • The perfect moment for execution? • “Enter Hamlet” ready to act the executioner. • But he decides not to execute Claudius. Why? • How does he now conceive of his revenge? • Does he taint his mind in this redefining of vengeance? • Given this motivation, is not acting worse than acting at this point? The “closet scene” with Gertrude • The decisive moment when Hamlet, previously agent of vengeance, turns murderer himself. • Line 21 indicates Hamlet seems to threaten violence to Gertrude. • Accuses her of murder of Hamlet Sr. • Insists on the comparison of her two husbands, ll. 53ff. • His insistence on her corruption, 91ff, 96ff. Return of the ghost: “To whet thy almost blunted purpose” • Hamlet seems to admit his having failed to act at the right moment: ll. 106ff. • “Amazement on thy mother sits./ O step between her and her fighting soul!” • The second part of the ghost’s command: “nor let thy soul contrive against thy mother aught.” • Has he offended against this too? • His seeming obsession with his mother’s corruption: ll. 181ff. The impossibility of Hamlet’s position • The ghost whips him to an emotional fury against both Claudius and Gertrude. • Then tells him not to taint his mind or harm his mother. • He’s to kill his uncle, who has killed his father in cold blood, but not “taint” his mind with passion or anger. • He’s to murder his mother’s husband, but not “contrive” against her. • These two scenes the turning point of the play? • Now the Polonius family have precisely the same motive of vengeance against Hamlet as he has against Claudius.