acquired brain injury as a result of unregulated stress

advertisement

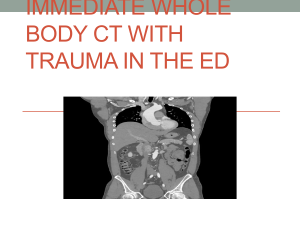

Understanding Trauma (1) About trauma Trauma means injury In the context of recent research on brain function, trauma has a specialised meaning – it means acquired brain injury as a result of unregulated stress Usually stress is good for us – when we can regulate stress, it enables us to function at our best But when for some reason we are not able to regulate stress we receive an overdose of stress hormones that is toxic to the brain – traumatic stress Changed blood supply to key brain areas then leads to lasting injuries, from which we will need to recover Trauma is a normal part of human life © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (2) The impact of trauma Traumatised people may find it difficult to: Self-regulate – stress, mood, impulses Process information accurately – make sense of the world around them and of their inner world of feelings Make and maintain relationships – understand and be interested in the inner world of others These difficulties have an impact on everyone involved In addition, those who live and work with the traumatised person may be affected by secondary trauma Attitudes and behaviour may change The network around the victim of trauma may disintegrate © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (3) What leads to unregulated stress? Two key factors The extent of the stress Our vulnerability – how able we are to self-regulate Some stress is so great that anyone would be injured by it Some people are so vulnerable that any stress may injure them Everyone is vulnerable to trauma Resilience and vulnerability change constantly © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (4) What makes us vulnerable? Being physically or emotionally depleted Health Grief and loss Other external stresses Lacking resilience Chronic depletion – health, prolonged duress, multiple losses Previous trauma Unmet attachment needs from early childhood © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (5) Attachment and resilience to trauma Humans are not born with the ability to regulate stress Babies 'catch ' this ability from their carers by patterning Attunement between the baby and the carer is the key to developing stress regulation When the baby is stressed the baby cries This causes stress in the carer As the adult soothes the baby their own acquired stress modifies The attuned baby follows the change in physiology in the adult This creates a brain pattern linking soothing with relaxation This is the basis for stress regulation for life © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (6) Vulnerable people .. .. may be less able to self-regulate stress They may quickly become hyperaroused They may dissociate and be switched off They may alternate between these extremes They may be driven by unmet baby needs to generate stress in others around them, especially those with whom they have an attachment relationship .. are more likely to be traumatised Being unable to self-regulate they can be injured by stresses that would not injure someone more resilient They may be driven to seek out high-risk situations They may be targeted by perpetrators of harm © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (7) The impact of being traumatised Regulatory disorders – challenging behaviour Stress – hyperarousal and dissociation Impulse – inability to manage or account for behaviour Shame – hypersensitivity to criticism or apparent lack of remorse © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (8) The impact of being traumatised Processing disorders – impaired understanding of: The world around them – difficulty making sense of sensory information Their inner world – difficulty making sense of feelings © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (9) The impact of being traumatised Social function disorders – social exclusion Understanding others – difficulty with empathy Feelings of worthlessness – difficulty with self-esteem Anhedonia – loss of the capacity for joy © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (10) Recovery phase one: Stabilisation Three levels of intervention to promote stabilisation Physiological: establishing safety Cognitive: teaching about trauma Emotional: teaching words for feelings © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (11) Recovery phase two: Integration Three levels of intervention to promote integration Physiological: teaching physiological self-management Cognitive: enabling cognitive restructuring Emotional: Enabling emotional processing © Kate Cairns Associates 2011 (12) Recovery phase three: Adaptation Three levels of intervention to promote adaptation Physiological: teaching social responsiveness Cognitive: building self-esteem Emotional: enabling the development of the capacity for joy © Kate Cairns Associates 2011

![The mysterious Benedict society[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005310565_1-e9948b5ddd1c202ee3a03036ea446d49-300x300.png)