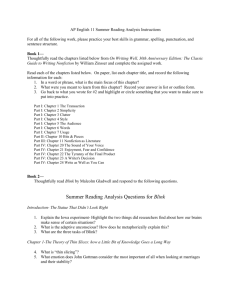

Claims, Reasons, Evidence & Warrants from Blink part 2

Claims, Reasons, Evidence & Warrants from

Blink part 2

• In this review, I go over the main stories that Gladwell talks about in the second part of the book (Chapters 5, 6 and conclusion) This time, however, I try to see the stories in terms of claims, reasons, evidence and warrants. I take the position that each chapter is an argument in itself, and each story is evidence which constructs the argument.

•

Not all of the arguments Gladwell makes contain all the elements, however, and remember that often these elements are implicit – that is, they are not stated directly.

• Remember that each story is used as evidence for a main claim, and often supports a sub-claim that is part of the main claim. So it isn`t always simple

•

As for acknowledgement, I think we can agree that Gladwell is not strong on this component of argument – His book would be stronger if he thought about potential criticisms of his views.

Chapter 5: Kenna`s dilemma

• Claim: Experts have special knowledge in their fields that permit them to exercise Blink thinking, but they need to do the « thin slicing » within a context. We can find the main claim for Chapter 5 on p 179 &

183

• Reason: Because experts spend a great deal of effort and time and thought on this field, they naturally have more developed ways of understanding the field, but they still need the context to pick up on the signals that others might miss.

• Warrant: A general principle like: Sometimes life doesn’t turn out the way you might expect it, because other unexpected factors affect the situation . Notice that this principle applies on all of the examples in

Chapter 5

Evidence for Chapter 5

Evidence 1

People who play and know music really like Kenna, but he can’t reach the success he would like because non-expert “focus groups” hearing the music out of context don’t permit him to get the airplay he needs.

(Note: We could counter-argue that Gladwell uses another example in the conclusion that contradicts this need for context – the woman behind the screen plays the trombone the best. With no context. )

Evidence for Chapter 5

A Second Look at First Impressions

• Evidence 2:

Bill Clinton was one of the first politicians to apply market research to the project of getting elected. But what does this kind of information from people tell us?

• By using an unpopular concept (political polling instead of using principle) Gladwell creates the unstable situation that he promises to render stable. Most of us don’t like politicians who act according to the polls, and don’t think our thoughts reflect the polls.

So the warrant is established here: that things are not always what they seem. This is a general principle that we can all understand and agree with

Evidence for Chapter 5:

Pepsi’s Challenge

• Evidence 3:

Coke made the mistake of imitating Pepsi, and it was a mistake because the taste test favors a certain kind of decontextualized reaction, which has little to do with how people drink Coke. Knowing how people react to

Coke requires a little important context, including the packaging, like other products such as margarine and brandy.

Evidence for Chapter 5

The Chair of Death

• Evidence 4:

the Aeron chair shows that sometimes average people don’t really understand their own reactions.

In this case, the chair was NEW, not ugly, in the minds of the people, but market research didn’t pick up on this difference, as it didn’t for some famous TV shows, and perhaps for Kenna the musician.

• This example furthers the claim that non-experts often don’t accurately describe their reactions.

Evidence for Chapter 5

the Gift of Expertise

• Evidence 5:

The professional tasters have a vocabulary and an ability to think about what they are tasting, while they are tasting. Non-experts actually get more confused when talking about things that are subconscious.

•

The jam tasters example shows that people can taste jam as well as experts, but when they try to talk about why they like the jam, they fail miserably

• Gladwell then goes back to his original examples (the tennis coach) and makes the distinction between being an expert at solving a problem, and knowing your own mind. To me, this is a weakness in his argument because Braden was supposed to be an expert in the beginning. But I do agree with G’s last statement of his claim in this chapter on p 184 “Whenever we have something that we are good at – something we care about, that experience and passion fundamentally change the nature of our first impressions ”.

Chapter 6

Seven Seconds in the Bronx

• Claim:

G makes his claim on page 232 when he says, “I think that we become temporarily autistic also in situations when we run out of time”. In other words, we are normally good at understanding each others emotions and intentions, but in panic situations, we lose this

“blink” ability because of our primitive reaction to a lack of time.

•

Reason:

Because we are in primitive survival mode, our ability to think with any complexity is affected.

• Warrant:

I think the warrant here is the general principle “We all will do whatever it takes to survive, because nature has made us instinctive self-defenders. (If we have any sympathy for the police officers, it is because they appear to truly fear for their lives.)

Evidence for Chapter 5

The case of Amadou Diallo:

• Four police officers make a terrible mistake (perhaps based on racism) and in their fear, kill an innocent man because they think he is drawing a gun. Because of the lack of time

(white space) they totally misjudge Diallo. (mind reading failure)

Evidence for Chapter 6

Paul Ekman and Face Reading

• Ekman became an expert on reading facial expressions and created a list of the involuntary facial expressions that we make every day. In normal situations we subconsciously use these expressions to read the minds of people.

• G. makes this sub-claim on page 213: “What Ekman is describing, in a very real sense, is the physiological basis of how we thin-slice other people”

Evidence for Chapter 6

The Case of Peter

• Peter, an autistic man, is “mind-blind” – he cannot understand people’s intentions from their expressions or gestures. Gladwell spends some time on this piece of evidence because he needs to convince us of the similarity between chronic autism and temporary autism – what he thinks the police officers had when they killed Amadou

Diallo. He proposes this claim as a question on p 221.

Evidence for Chapter 6

Arguing with a Dog

• The title here suggests that when we are in an extreme state of arousal because of danger, and our heart rate goes over

145, we become more like an animal because we start using the more animal-like part of our brain. G describes many police situations such as high-speed chases where officers simply lose control.

• G makes this claim in a very short sentence on page 229:

“Arousal leaves us mind-blind”.

Evidence for Chapter 6

Running out of White Space

• Gladwell makes the point here that a lack of time pressures people (security and police in particular) so that they can’t think clearly. He describes two assassination attempts and various police situations to suggest that slowing down the situation allows for more complex thought.

• Note: At this point, you might be wondering “But I thought Blink was lightning-fast thought ! Now Gladwell wants to slow it down” ? I think

Gladwell would strengthen his argument here by acknowledging this natural criticism of his argument. But there is no acknowledgment.

Can you sense this weakness in his writing?

Evidence for Chapter 6

Something told me not to shoot

• In this section, Gladwell makes the point that Blink thinking in periods of high stress can be trained. Security people can be trained to control their primitive reactions.

• This sub-claim is stated directly on page 238: “Mindreading, as well, is an ability that improves with practice.”

• Gladwell then moves back to the Diallo story, and by redescribing it, concludes the claim that in this particular case, and therefore in other cases, a primitive response and lack of time lead to mind-blindness.

Conclusion

Listening with your Eyes

• Claim:

Our prejudices can affect our rapid cognition, but when they are taken away, we are capable of great “Blink power”

• Reason:

This is true because people have prejudices and use them to make decisions

• Warrant:

A general principle such as: Life is not always fair

• Evidence:

when Abbie Conant played the trombone behind the screen, the experts immediately recognized her as the best. But when she emerged from behind the screen and they saw she was a woman, they came face to face with their Blink ability versus their prejudices.