Chapter 17

advertisement

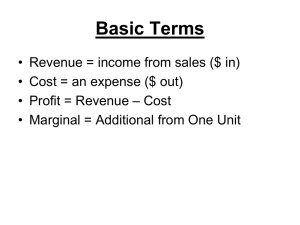

© 2013 Pearson Which cell phone? © 2013 Pearson 17 Monopolistic Competition CHAPTER CHECKLIST When you have completed your study of this chapter, you will be able to 1 Describe and identify monopolistic competition. 2 Explain how a firm in monopolistic competition determines its output and price in the short run and the long run. 3 Explain why advertising costs are high and why firms use brand names in monopolistic competition. © 2013 Pearson 17.1 WHAT IS MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION? Monopolistic competition is a market structure in which • A large number of firms compete. • Each firm produces a differentiated product. • Firms compete on price, product quality, and marketing. • Firms are free to enter and exit. © 2013 Pearson 17.1 WHAT IS MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION? Large Number of Firms Like perfect competition, the market has a large number of firms. Three implications are • Small market share • No market dominance • Collusion impossible © 2013 Pearson 17.1 WHAT IS MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION? Product Differentation Product differentiation is making a product that is slightly different from the products of competing firms. A differentiated product has close substitutes but it does not have perfect substitutes. When the price of one firm’s product rises, the quantity demanded of that firm’s product decreases. © 2013 Pearson 17.1 WHAT IS MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION? Competing on Quality, Price, and Marketing Quality Design, reliability, after-sales service, and buyer’s ease of access to the product. Price Because of product differentiation, the demand curve for the firms’ product is downward sloping. Marketing Marketing has two main forms: Advertising and packaging. © 2013 Pearson 17.1 WHAT IS MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION? Entry and Exit No barriers to entry. So the firm cannot make economic profit in the long run. Identifying Monopolistic Competition Two indexes: • The four-firm concentration ratio • The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index © 2013 Pearson 17.1 WHAT IS MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION? The Four-Firm Concentration Ratio The four-firm concentration ratio is the percentage of the value of sales accounted for by the four largest firms in the industry. The range of concentration ratio is from almost zero for perfect competition to 100 percent for monopoly. • A ratio that exceeds 60 percent is an indication of oligopoly. • A ratio of less than 40 percent is an indication of a competitive market—monopolistic competition. © 2013 Pearson 17.1 WHAT IS MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION? The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is the square of the percentage market share of each firm summed over the largest 50 firms in a market. For example, if four firms have market shares of 50 percent, 25 percent, 15 percent, and 10 percent, then HHI = 502 + 252 + 152 + 102 = 3,450. A market with an HHI of less than 1,000 is regarded as competitive and between 1,000 and 1,800 is moderately competitive. © 2013 Pearson 17.1 WHAT IS MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION? Limitations of Concentration Measures The two main limitations of concentration measures alone as determinants of market structure are their failure to take proper account of • The geographical scope of a market • Barriers to entry and firm turnover © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS How, given its costs and the demand for its jeans, does Tommy Hilfiger decide the quantity of jeans to produce and the price at which to sell them? The Firm’s Profit-Maximizing Decision The firm in monopolistic competition makes its output and price decision just like a monopoly firm does. Figure 17.1 on the next slide illustrates this decision. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS 1. Profit is maximized when MR = MC. 2. The profit-maximizing output is 125 pairs of Tommy jeans per day. 3. The profit-maximizing price is $75 per pair. ATC is $25 per pair, so 4. The firm makes an economic profit of $6,250 a day. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS Profit Maximizing Might Be Loss Minimizing Some firms in monopolistic competition have a tough time making a profit. A burst of entry into an industry can limit the demand for each firm’s own product. Figure 17.2 on the next slide illustrates a firm incurring a loss in the short run. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS 1. Loss is minimized when MC = MR. 2. The loss-minimizing output is 40,000 customers and 3. The price is $40 per month, which is less than ATC. 4. The firm incurs an economic loss. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS Long Run: Zero Economic Profit Economic profit induces entry and economic loss induces exit, as in perfect competition. Entry decreases the demand for the product of each firm. Exit increases the demand for the product of each firm. In the long run, economic profit is competed away and firms make zero economic profit. Figure 17.3 on the next slide illustrates long-run equilibrium. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS 1. The output that maximizes profit is 75 pairs of Tommy jeans a day. 2. The price is $50 per pair. Average total cost is also $50 per pair. 3. Economic profit is zero. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS Monopolistic Competition and Perfect Competition The two key differences between monopolistic competition and perfect competition are that in monopolistic competition, there is • Excess capacity • A markup of price over marginal cost © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS Excess Capacity A firm has excess capacity if the quantity it produces is less that the quantity at which average total cost is a minimum. A firm’s efficient scale is the quantity of production at which average total cost is a minimum. Markup A firm’s markup is the amount by which price exceeds marginal cost. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS 1. The efficient scale is 100 pairs of Tommy jeans a day. 2. The firm produces less than the efficient scale and has excess capacity. 3. Price exceeds 4. marginal cost by the amount of 5. the markup. 6. Deadweight loss arise. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS In perfect competition, 1. The efficient quantity is produced and 2. Price equals marginal cost. © 2013 Pearson 17.2 OUTPUT AND PRICE DECISIONS Is Monopolistic Competition Efficient? Deadweight Loss Because price exceeds marginal cost, monopolistic competition creates deadweight loss—an indicator of inefficiency. Making the Relevant Comparison Price exceeds marginal cost because of product differentiation. But product variety is valued. The Bottom Line Product variety is both valued and costly. But compared to the alternative, monopolistic competition looks efficient. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Product Development Wherever economic profits are earned, imitators emerge. To maintain economic profit, a firm must seek out new products. Profit-Maximizing Product Development When the marginal cost of a better product equals the marginal revenue from a better product, the firm is doing the profit-maximizing amount of product development. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Efficiency and Product Development Regardless of whether a product improvement is real or imagined, its value to the consumer is its marginal benefit, which equals the amount the consumer is willing to pay. The marginal benefit to the producer is the marginal revenue, which in equilibrium equals marginal cost. Because price exceeds marginal cost, product improvement is not pushed to its efficient level. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Marketing Firms in monopolistic competition spend a large amount on advertising and packaging their products. Marketing Expenditures A large proportion of the prices that we pay cover the cost of selling a good. Eye On Your Life shows the selling costs that you pay when you buy a new pair of running shoes. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Selling Costs and Total Costs Advertising expenditures increase the costs of a monopolistically competitive firm above those of a perfectly competitive firm or a monopoly. Advertising costs are fixed costs. Advertising costs per unit decrease as production increases. Figure 17.5 on the next slide illustrates the effects of selling costs on total cost. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING 1. When advertising costs are added to 2. The average total cost of production, 3. Average total cost increases by a greater amount at small outputs than at large outputs. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING 4. If advertising enables sales to increase from 25 pairs of jeans a day to 100 pairs a day, the average total cost falls from $60 a pair to $40 a pair. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Selling Costs and Demand Advertising and other selling efforts change the demand for a firm’s product. The effects are complex: • A firm’s own advertising increases the demand for its product. • Advertising by all firms might decrease the demand for any one firm’s product and might make demand more elastic. The price and markup might fall. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Figure 17.6 shows the possible effect of advertising. 1. With no advertising, demand is low but 2. The markup is large. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING With advertising, average total cost increases. If advertising enables more firms to survive, new firms might be encouraged to enter the market. The number of firms in the market might increase. The demand for any one firm’s product decreases. If all firms advertise, the demand for any one firm’s product becomes more elastic. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING With advertising, average total cost increases and the ATC curve becomes ATC1. If all firms advertise, demand for one firm’s product decreases and becomes more elastic. Profit-maximizing output increases, the price falls, and the markup shrinks. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Using Advertising to Signal Quality Some advertising is very costly and has almost no information content about the item being advertised. Such advertising is used to signal high quality. A signal is an action taken by an informed person or firm to send a message to uninformed people. Signaling works because it is profitable to signal high quality and deliver it but unprofitable to signal a high quality product and not deliver it. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Brand Names Brand names are also used to provide information about the quality of a product. It is costly to establish a widely recognized brand name. Like costly advertising, a brand name signals high quality. Brand names work because it is unprofitable to incur the cost of creating a brand name and then deliver a low quality product. © 2013 Pearson 17.3 PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND MARKETING Efficiency of Advertising and Brand Names Advertising and brand names that provide information about the quality of products enable buyers to make better choices. Advertising and brand name can be efficient if the marginal cost of the information equals its marginal benefit. The final verdict on the efficiency of monopolistic competition is ambiguous. © 2013 Pearson Which Cell Phone? There is a lot of product differentiation in cell phones: Nokia makes 143; versions; Samsung makes 103; and Sony Ericsson makes 100. In the three months from April through June 2011, hundreds of new varieties of cell phones were announced by the top 20 firms in this market. Why is there so much variety in cell phones? The answer is that preferences are diverse and the cost of matching the diversity of preference is low. © 2013 Pearson Which Cell Phone? Think about the ways in which cell phones differ. Just a few of them are its dimensions, weight, navigation tools, talk time, standby time, screen, camera features, audio features, memory, connectivity, processor speed, storage, and network capability. Each one of these features comes in dozens of varieties. How many possible designs? For example, if a phone had 10 features and each feature comes in 6 varieties, there are 1 million different possible designs. © 2013 Pearson Which Cell Phone? Firms produce variety only when the marginal cost of doing so is less than the marginal benefit. The marginal cost of some cell-phone variety is not large. But a new way of adding variety that has almost no cost will bring product differentiation that makes each cell phone unique to the preferences of each individual. This new way is the cell-phone application. Apple has only two versions of the iPhone, but each iPhone owner can load their phone with exactly the program applications they want. © 2013 Pearson Which Cell Phone? In the long run, entry and innovation by each producer will drive the economic profit toward zero. The pursuit of economic profit will spur ever more innovation. Consumers will be confronted with ever wider choice. © 2013 Pearson