Sociolinguistics

Gender

Dr Emma Moore

1

Contents

2

What is gender?

When did linguists start thinking about

gender?

What have variationist sociolinguists found

out about gender?

What have interactional sociolinguists found

out about gender?

What is gender?

3

Sex = a biological

category

Gender = a social and

cultural concept

Is the way we behave (our gender)

determined/constrained by our biology (our sex)?

How Are We Gendered?

4

At birth:

How Are We Gendered?

5

In childhood:

How Are We Gendered?

6

In adulthood:

Early Linguists’ Views

Women’s language requires explanation

–

Jesperson (1922): “The Woman”

7

Women talk more than men: “The volubility of women

has been the subject of innumerable jests”

Women make excessive use of descriptive forms: “the

fondness of women for hyperbole will very often lead the

fashion with regard to adverbs of intensity”

Women are conservative speakers: “as a rule women

are more conservative than men … while innovations

are due to the initiative of men”

Types of research

Variationist sociolinguistics

–

Interactional sociolinguistics

–

8

Quantitative

Qualitative

Variationist Studies of Gender

Early survey studies found differences in

male/female use of language

–

9

Labov (1966), Trudgill (1974): When all other

social factors are held constant, women use more

standard variants than do men

Is this a universal?

The Sex/Prestige Pattern (Hudson 1996: 195)

In any society where males and females have equal access to

the standard form, females use standard variants of any stable

variable which is socially stratified for both sexes more often

than males do.

10

Labov (1966, 1972): NYC, USA

Wolfram (1969): Detroit, USA

Trudgill (1974): Norwich, UK

Macauley (1978): Glasgow, UK

Cheshire (1982): Reading, UK

Explaining the sex/prestige pattern

Status and prestige

–

Socialisation

–

11

Women are more sensitive to “overt

sociolinguistic values” (Labov 1972: 243)

Sex differences occur as a consequence

of gender norms (Labov 1972: 304)

Evidence: Trudgill (1974)’s data on

self-reporting

Trudgill (1974): variation in ear, here

–

1. /ɪə/ 2. /ε:/

% informants

12

Total

Male

Female

Over-reporting

43

22

68

Under-reporting

33

50

14

Accurate

23

28

18

Men under-report use

of the standard form

Women over-report use

of the standard form

Different pressures exerted on men

and women

Men: affected by the covert prestige of

vernacular variants

–

Associations with masculinity

“… WC speech, like many aspects of WC culture,

has, in our society, connotations of masculinity,

since it is associated with the roughness and

toughness supposedly characteristics of WC life,

which are, to a certain extent, considered to be

desireable masculine attributes” (Trudgill 1974).

13

Different pressures exerted on men

and women

Women: affected by the overt prestige of

standard variants

–

14

Associations with social status & power

“The social position of women in our society is less secure than

that of men … It is therefore necessary for women to secure and

signal their social status linguistically and in other ways, and they

are more aware of the importance of this type of signal … Since

[women] cannot be rated socially by their occupation, by what

other people know about what they do in life, other signals of

status, including speech, are correspondingly more important”

(Trudgill 1974).

Language, gender and employment

15

Employment: Sankoff et al. (1989): women are

“technicians of language”

More evidence: Gal (1978, 1998)

“Peasant Men Can’t Get Wives”

–

–

Ethnographic study of Austrian village, Oberwart

Languages: Hungarian (traditional); German

(language of incomers)

–

Different networks:

16

Women leading the shift to German

Peasant (traditional farming)

Non-peasant (commercial)

Gal (1978, 1998): Male data

Shaded boxes

= peasant

networks

Unshaded

boxes = nonpeasant

networks

17

For men, use of German increases

with:

YOUTH, NON-PEASANT NETWORKS

Gal (1978, 1998): Female data

18

For women, use of German increases with:

Oldest category: no non-peasant networks

Middle category: NON-PEASANT NETWORKS

Youngest category: More German than any other category, irrespective of

network

Gender, status and language use in

Oberwart

Access to different forms of status in the

community

–

Peasantry:

–

men control/inherit land women do

housework/agricultural work

Non-peasant networks:

Enable women to gain financial/social independence

–

19

Women pursue jobs and husbands in this network thus

use more German to enable access to this network

irrespective of their background

Status and gender

These studies suggest that different pressure

operate on men and women

–

–

–

20

Status

Prestige

Opportunities and social contexts

And these pressure affect language use

More recent variationist studies…

Finding ways to analyse different settings

–

Milroy’s (1980) network study

–

Eckert’s (2000) community of practice

21

Network involvement not just gender

Social practice not just gender

Interactional studies of gender

Early studies explored differences in

male/female discourse styles

–

22

Not just differences in the kind of variants but also

differences in whole conversational styles

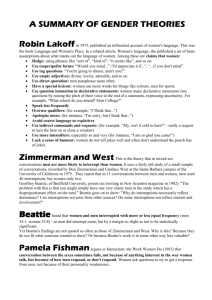

Lakoff ([1975] 2004): Language and

Woman’s Place

‘women’s language’ – meaning both language

restricted in its use to women and language

descriptive of women alone.

(Lakoff [1975] 2004: 42).

Elements of ‘women’s language’

according to Lakoff (1975)

Women use more expressive lexis e.g.

–

–

W:

The weather’s awful, isn’t it?

Women’s language

reflects ‘weakness’/

lack of assertion

Women are indirect

–

–

23

The wall is mauve

The wall is pink

Women use tag questions

–

W:

M:

A:

B:

Can you meet me at 6?

Well, I have a doctor’s appointment at

5.45.

Explanations of gender differences

Deficit?

–

Women’s language as inadequate

Dominance?

–

“I think that the decisive factor is less purely gender than

power in the real world. But it happens that, as a result of

natural gender, a woman tends to have, and certainly tends

to feel she has, little real-world power compared with a man;

so generally a woman will be more apt to have these uses

than a man will” (Lakoff [1975] 2004: 82).

24

Women’s language use a consequence of their lack of power

Explanations of gender differences

Difference?

–

25

“If a little girl “talks rough” like a boy, she will

normally be ostracized, scolded, or made fun

of. In this way society, in the form of a child’s

parents and friends, keeps her in line, in her

place. This socializing process is, in most of its

aspects, harmless and often necessary, but in

this particular instance – the teaching of

special linguistic uses to little girls – it raises

serious problems, though the teachers may

well be unaware of this” (Lakoff [1975] 2004:

40).

Studies…

Fishman (1983): Who does the most conversational

work in heterosexual partnerships?

–

–

Goodwin (1980): How do boys and girls use

language to negotiate play?

–

–

26

Men control the conversational floor

Women as conversational ‘shit-workers’ (questions, support

etc.)

Boys hierarchical

Girls collaborative

Summing up…

Variationist sociolinguists have found very consistent

patterns of gender differences

–

Interactional sociolinguists have also noted

differences in male/female discourse styles

Both types of study provide similar explanations for

gender differences

–

–

–

27

Women tend to use more standard variants than men

Theories about status & class associations

Theories about power

Theories about socialisation

References and Reading

Coates, Jennifer (2004) Women, Men and Language, Third Edition. Routledge:

London.

Eckert, Penelope (1998) “Gender and sociolinguistic variation”. In: Jennifer

Coates (ed.), Language and Gender: A Reader, 64-75. Oxford: Blackwell.

Fishman, Pamela (1983) “Interaction: The work women do”. In: Barrie Thorne,

Cheris Kramarae and Nancy Henley (eds.), Language, Gender and Society, 89101. Cambridge: Newbury House Publishers.

Jesperson, Otto (1922) “The woman”. In: Language: Its Nature, Development

and Origin. London: Allen & Unwin. [Reprinted in: Cameron, Deborah (ed.)

(1990) The Feminist Critique of Language: A Reader, 201-220. London:

Routledge.]

Lakoff, Robin ([1975] 2004) Language and Woman’s Place: Text and

Commentaries. Revised edition (edited by Mary Bucholtz). Oxford: OUP

Tannen, Deborah (1990) You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in

Conversation. London: Virago Press.

Required Reading: Meyerhoff (2006: Chapter 10)

28