Edward Taylor and the Metaphysical Poets

English 441

September 8, 2010

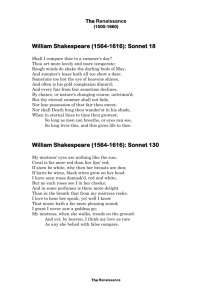

The term "metaphysical poets" designates the work of 17th-century English poets who were using similar methods and who revolted against the romantic conventionalism of

Elizabethan love poetry that was prevalent from ~1550 – 1600. Think Shakespeare’s sonnets!

a penchant for imagery that is novel,

"unpoetical" and sometimes shocking, drawn from the commonplace (actual life) or the remote (erudite sources), including use of the metaphysical conceit

The best metaphysical poetry is honest,

unconventional, and reveals the poet's sense of the complexities and contradictions of life.

It is intellectual, analytical, psychological, and bold; frequently it is absorbed in thoughts of death, physical love, and religious devotion.

In England, John Donne was the acknowledged leader of the metaphysical poets (though they themselves would not have used the term, nor have considered themselves to constitute a "school" of poetry).

We see the influence of these metaphysical poets in early America in the likes of Anne

Bradstreet and Edward Taylor. We talked about Anne Bradstreet’s use of metaphysical conceits last week, specifically her poems

“The Author to Her Book” and “In Reference to Her Children, 23 June 1659.”

But in Edward Taylor, his leanings toward metaphysical poetry are even stronger, specifically his poems “Huswifery” and “A Fig for Thee, Oh! Death”

A far-fetched and ingenious extended comparison used by metaphysical poets to explore all areas of knowledge. It finds telling and unusual analogies for the poet's ideas in the startlingly esoteric or the shockingly commonplace -- not the usual stuff of poetic metaphor.

MARK but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deniest me is;

It suck'd me first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be.

Thou know'st that this cannot be said

A sin, nor shame, nor loss of maidenhead;

Yet this enjoys before it woo,

And pamper'd swells with one blood made of two;

And this, alas ! is more than we would do.

O stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where we almost, yea, more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is.

Though parents grudge, and you, we're met,

And cloister'd in these living walls of jet.

Though use make you apt to kill me,

Let not to that self-murder added be,

And sacrilege, three sins in killing three.

Cruel and sudden, hast thou since

Purpled thy nail in blood of innocence?

Wherein could this flea guilty be,

Except in that drop which it suck'd from thee?

Yet thou triumph'st, and say'st that thou

Find'st not thyself nor me the weaker now.

'Tis true ; then learn how false fears be;

Just so much honour, when thou yield'st to me,

Will waste, as this flea's death took life from thee.

1633

Note the use of domestic imagery in

"Huswifery." Why do you think Taylor chooses imagery taken from the domestic sphere to express his religious sentiments in this poem?

Is it significant that his God is here presented as a housewife rather than, say, a judge or a soldier?

DEATH be not proud, though some have called thee

Mighty and dreadfull, for, thou art not so,

For, those, whom thou think'st, thou dost overthrow,

Die not, poore death, nor yet canst thou kill me.

From rest and sleepe, which but thy pictures bee,

Much pleasure, then from thee, much more must flow,

And soonest our best men with thee doe goe,

Rest of their bones, and soules deliverie.

Thou art slave to Fate, Chance, kings, and desperate men,

And dost with poyson, warre, and sicknesse dwell,

And poppie, or charmes can make us sleepe as well,

And better then thy stroake; why swell'st thou then;

One short sleepe past, wee wake eternally,

And death shall be no more; death, thou shalt die. 1633

How does Taylor’s poem differ from Donne’s?