NSERC Evaluation

advertisement

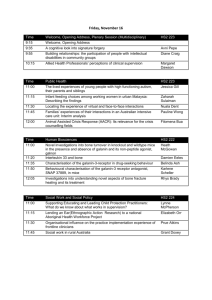

NSERC Evaluation How do I improve my grant? Scott McIndoe Chemistry EG 2010-2013 F100 Follow the rules: use the standard headings AS A GUIDE. Not mandatory. Number your references, but if you need the room, be selective, i.e. 23. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 21. Inorg. Chem. is probably just as good as: 23. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 22. Austr. J. Chem. 21. Inorg. Chem. A paragraph for HQP is not good enough. Are the titles of your student’s 20 poster presentations important? No. Is the fact that your students have presented 20 posters at conferences important? Yes! Budget justification Keep it short. Demonstrate that you’ve thought about the budget; include all the important categories, but don’t make it super-detailed. Basically, you want the reviewers to skim this section and check that you’ve done due diligence. There is no cost-of-research determination; all programs are assumed to have a “normal” cost. DO make sure you err on the high side. If you ask for $70k, and are put in a bin that gives you $80k, you will get $70k only. Exception: DAS. Relationship to other support Keep it short and clear. Explain the conceptual differences between your DG and other funding. Excellence of the researcher Publish a lot in good journals. (Awards, citations, h-index (last 6 years), patents, funding, special considerations, invitations to speak, reputation, collaborations, reviews/books/chapters, service, refereeing, etc. all help, but are less determinative) Merit of the proposal Start by saying what your program is, why it matters, and how it is original. Don’t repeat yourself. If you’ve highlighted past work in your F100, don’t repeat it in your F101. Just enough past work to provide context on what you’re planning. Include strong continuation work AND high risk/high reward ideas. Eliminate all trivial errors (typos, spelling mistakes, grammatical errors, unfinished sentences, misnumbered references). These don’t affect the scientific case but they make you look sloppy. Don’t get fancy with font choices, font colour, text formatting, etc. Your stylistic choices might impress you but will likely irritate the reviewers. Bolding key statements is a good idea, but don’t overdo it. Make sure your proposal is readable, i.e. include white space. A break does not need to be a full line in thickness to improve readability. Use colour figures, but ensure that they are readable in black and white. Try and hit a balance between readability and density. “Ahhh…” “Arghh…” Why is your work important? You need to be self-critical here, and ask people other than experts to be brutally honest when evaluating your proposal on this basis. Too many applicants are excited about their research, and assume that everyone else knows about the driving forces for conducting it. That’s a dangerous assumption, and you’re relying on others (EG, referees) to do the job for you. The committee is not, for the most part, experts in your area. Generally, most of your reviewers are. Finding the balance between your audiences is tricky, but too general and too wonky are both mistakes. Don’t stay in the shallows; don’t jump in at the deep end; move from one to the other. Include at least one credible idea, which if it works, the results will end up in a very high impact journal. Sound positive, no matter how dire your circumstances. Don’t whine: everyone faces challenges. Explain how you made the best of it. The committee does pro rate leaves of absence, lab disasters etc, but they need hard numbers to do this. 6 weeks of sick leave over 6 years is nothing. 12 months of maternity leave is something. However, the pro-rating will often not move someone up a level – each rank (Strong, Very Strong, etc) is quite wide. Use the lay summary well. It gets read. It shouldn’t be a repeat of your proposal introduction or conclusions. Write it now. Go back to it. Get other people to read it. Rewrite it. Find a non-chemist, and read it to them. Write it again. Don’t leave it to the end. Don’t repeat yourself. Annoying, isn’t it? Your application is not a paper – it doesn’t need an abstract, introduction, discussion and conclusions. References (now 2 pages) Don’t play games with fonts, spacing, weird abbreviations etc. Don’t reference your own work again. Just cross-reference your F100. Do cite the work of others in the field, and be positive about their work. Two pages is probably more than you need, but you should use it all. Flatter potential reviewers by citing them (only if appropriate, of course!). Use footnotes to clarify a point or claim that otherwise disrupts the flow of your proposal. Citing current, high-impact work makes your work appear more important and relevant. Proposals that get most heavily bashed by reviewers are those that reveal a lack of awareness of the state-of-the-art. Do your homework! At the very least, run searches on your proposal title… your reviewers will. Good HQP arguments Sound passionate about teaching and mentoring your graduate students. The most persuasive arguments were made by people who sounded like they are strongly engaged with their students: this doesn’t mean micromanagement, but rather equipping students with the tools needed for success in their field. Explain why your training is unique. What do you give your students that no one else in Canada can provide? Explain why your training is important. What jobs are your students going to that Canada desperately needs filling? Explain why your training provides your students with opportunities. Conferences, travel, collaboration, interaction with industry, training other than in your laboratory/department. Explain why your training provides your students with great outcomes. If your students go on to do well, talk about it. Make it clear you know who your students are. Name names. Know what they’re doing now. “Unknown”, “Name withheld” both look bad. New page for HQP The F101 now has a separate page for HQP, which probably lessens the need to integrate your HQP account into the proposal. However, the committee still wants to hear what it is your students will be doing. If you have the same individual listed multiple times, explain why this scenario was advantageous for the HQP in question. Do NOT repeat the HQP section from your F100! Verbatim is verboten, and rehashing the same material looks lazy. I recommend focusing on HQP outcomes in your F100 (the past), and on training philosophy and plans in the F101 (the future). Groups that are grad student-heavy tend to score highest. PhD > MSc > postdoc > undergraduate > research assistant/technician (partly a function of time-ingroup, but more “extent-to-which-you’re-responsible-for-this-person’s-training”). As far as outcomes for undergrads: jobs and grad school are seen as positives. Professional programs are seen as neutral. “Unknown” and “name withheld” are seen to indicate a lack of interest. Unemployed HQP are seen negatively. Reviewers The most influential reviewers tend to be successful, conscientious, mid-career researchers. The best reviews are balanced: they highlight the strong points and the weaknesses of the proposal. People who like you but are blandly positive without explaining why are ignored. People who dislike you but are negative without explaining why are ignored. Don’t pick reviewers who are in the EG! Do pick Canadian, DG-funded reviewers, unless you know an international person who understands the NSERC system. Try to avoid reviewers who are up for DG renewal in the same year as you. Suggested reviewers get used a LOT (especially ex-EG members)… … but remember each person can only do 3 DGs maximum. Being a reviewer… Your expertise and reliability is being gauged by the committee every time you act as a reviewer. People who write prompt, well-researched, succinct and frank appraisals get a good reputation.