Chapter_08_Micro_online_14e

advertisement

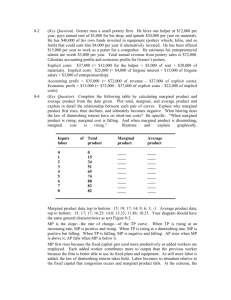

Micro Chapter 8 Costs and the Supply of Goods 7 Learning Goals: 1) Bring out the role costs play in making economic decisions 2) Define and differentiate between a short-run time period and a long-run time period 3) Define and calculate costs used to make decisions 4) Relate costs to output decisions in the short run 5) Relate costs to output decisions in the long run 6) Explore the factors that cause shifts in the cost curves 7) Explain how past, present, and future costs influence production decisions “From the standpoint of society as a whole, the “cost” of anything is the value that it has in alternative uses.” Thomas Sowell The Economic Role of Costs The demand for a product represents the voice of consumers instructing firms to produce the good. On the other hand, a firm’s costs represent the desire of consumers not to sacrifice goods that could be produced if the same resources were employed elsewhere. Economic profit ≠ Accounting profit Accounting profit = total revenue – total out-of-pocket costs Economic profit = total revenue – total outof-pocket costs – opportunity costs Zero economic profit referred to as normal profit rate Q8.1 The costs of a firm indicate the desire of consumers for 1. the product produced by the firm. 2. other goods that might have been produced with the same resources. 3. goods that can be easily substituted for the good produced by the firm. 4. goods that are complementary with the good produced by the firm. Q8.2 (MA) When a firm is earning economic profit, which of the following are necessarily false? 1. 2. 3. 4. The firm is increasing the value of the resources that it is using. The firm is reducing the value of the resources that it is using. The firm is supplying the market with a low quality product. The firm is creating less value for consumers than another firm that is currently earning losses. Short Run and Long Run Time Periods You must know these 2 definitions: Short Run (SR) – a period of time in which at least one input is fixed Long Run (LR) – a period of time in which all inputs are variable; i.e. none of the inputs are fixed Q8.3 The short run is a time period such that 1. 2. 3. 4. the existing firms in the market do not have sufficient time to change the amounts of any of the inputs that they employ. the existing firms in the market do not have sufficient time to either increase or decrease their current rate of output. the existing firms in the market do not have sufficient time to increase the size of their existing plant or build a new factory. new firms may build plants and enter the industry. Q8.4 The long run is a period of 1. 2. 3. 4. at least one year. sufficient length to allow a firm to expand output by hiring additional workers. sufficient length to allow a firm to alter its plant size and capacity and all other factors of production. sufficient length to allow a firm to transform economic losses into economic profits by hiring better workers. Categories of Costs Some costs are fixed – they don’t vary with quantity Some costs are variable – they vary with quantity Average costs are per unit costs Marginal cost is the change in total cost Output and Costs In the Short Run Watch video: Modern Times- Charlie Chaplin productivity Read and reread this section carefully. The ability of a firm to make stuff (its production) is intimately tied to costs You must understand why the cost curves look like they do, AND How they are related to production Here is the graph you need to know: Watch content video: Micro Chapter 08short run costs Why does MC first fall and then rise rapidly? MC initially falls for two reasons: (1) Increasing marginal returns- each additional input adds more to total output than the previous input (2) learning by doing Watch video: Groundhog Day-learning by doing Why does MC first fall and then rise rapidly? MC rises because of diminishing marginal returns At some point, each additional input adds less to total output than the previous input Since more and more input is required, marginal cost rises rapidly I left a stack of handouts containing a problem set by the door to the classroom today. Each student was supposed to pick one up. The problem was that, in the last three minutes before class started, the line of students waiting to pick up the handouts and walk through the entryway to the classroom was getting longer and longer. I had a brilliant idea- make two piles- and I did that. More students per minute were able to pick up the handout and walk into the classroom. With the addition of more of the variable input (piles of handouts), the output (students walking into class) increased. But despite my doubling the number of stacks, the number of students walking into class each minute didn’t double. The reason is that there was a fixed input- the size of the entryway into the room. If I had added a third pile, the output might have increased further, but not by very much. Even in distributing handouts before class, the principle of diminishing marginal productivity seems to work. Q: This story is similar to you leaving class. How could we increase the marginal return of getting students out of class? That is, how could we get more students out the doors in the same amount of time? What’s the relationship between MC and ATC? Just before class, my economics major students were laughing at a conversation they overheard between the instructor of the previous class and her student. The student said, “I really need a good grade in this class ‘cause my GPA has to be high for me to get into grad school.” My students were laughing because the grade in that particular class could not have had much of an effect on the senior’s GPA. The student (it wasn’t an economics class, thank goodness) did not distinguish marginal from average. The same thing happens among my intro students at least once a year. Someone tells me that unless he or she gets a B in my class, his or her GPA will be so low that he or she will be thrown out of the university. These students also don’t seem to know marginal from average. Their average is low because of their previous bad grades. The marginal grade- what they get in my class- is not going to affect their GPAs very much. What’s the relationship between MC and ATC? Illustration: your GPA Let’s say you’re a sophomore with a 3.0 cumulative GPA (analogous to ATC) Suppose this semester’s GPA (analogous to MC) is 3.5 – Your new cumulative would be higher (ATC rises) Now suppose this semester’s GPA (MC) is 2.0 – Your new cumulative would be lower (ATC falls) Then, next semester’s GPA (MC) is 2.5 – Your new cumulative would still be lower (ATC still falls) Catch phrase: “the average chases the margin” Q8.5 As output is expanded, if MC is more than ATC, 1. 2. 3. 4. ATC must be at its minimum. ATC must be at its maximum. ATC must be increasing. the firm must be earning economic profit. Q8.6 The short run average total cost (ATC) curve of a firm will tend to be U-shaped because 1. 2. 3. 4. larger firms always have lower per unit costs than smaller firms. at small output rates, AFC will be high while at large output rates MC will be high as the result of diminishing returns. diminishing returns will be present when output is small while high AFC will push per unit cost to high levels when output is large. increasing marginal returns will be present at both small and large output rates. Output and Costs In the Long Run Graph of LR Costs: Watch content video: Micro Chapter 08long run costs Why does LR ATC look like this? Because in order to produce larger quantities, the firm will need to “get bigger.” That is, they will need to increase their capital. These are typically expensive so capital costs become large which drives up LRATC. Economies of scale is the benefit to the firm from becoming larger. Economies of scale means the benefit is getting bigger (ATC is falling) – Also referred to as Increasing Returns to Scale Diseconomies of scale means the benefit is negative (ATC is rising) – Also referred to as Decreasing Returns to Scale What’s an efficient size for a church or synagogue? If there were economies of scale throughout, with all the Baptists in a big Texas city such as Austin, we’d see just one giant Baptist church. With 10,000 Jews in Austin, we’d see just one big synagogue. We don’t: There are many churches in each denomination, as well as many synagogues. As the city has expanded, more and more different kinds of Baptist churches, Jewish synagogues, and other churches have been organized. It’s not just that each one serves a local area. People drive a long way to the church or synagogue of their choice even when another one is closer. They like the peculiarities of a leader’s ministry, the type of service, and even the particular social interactions of a congregation. With one big house of worship, these choices would be lost. Statistical studies of the long-run average cost curves of churches suggest that this is true: There are economies of scale up to some size, but as the church or synagogue begins growing beyond a certain size, diseconomies of scale set in- it becomes less efficient. Q: List some of the cost and production factors that would create economies of scale then some factors that would create diseconomies of scale. Q 8.7 A downward-sloping portion of a longrun average total cost curve is the result of 1. 2. 3. 4. economies of scale. diseconomies of scale. diminishing returns. the existence of fixed resources. Q8.8 In the long run, a firm might experience rising per unit costs due to 1. 2. 3. 4. economies of scale. diseconomies of scale. the law of supply. the law of diminishing marginal returns. Summary: In the SR, diminishing returns determine the shape of the cost curves In the LR, economies of scale determine the shape of the cost curves What Factors Cause Cost Curves to Shift? Cost curves shift up and down Higher costs shift curves up: 1) Resources become more expensive 2) Higher taxes 3) More, or stricter, regulations 4) Older technology Lower costs shift curves down: 1) Resources become less expensive 2) Lower taxes 3) Less regulation 4) Newer technology Cost curves impact supply curves When cost curves shift up, supply shifts left When cost curves shift down, supply shifts right The Economic Way of Thinking about Costs Some costs should be ignored Sunk costs cannot be reversed or recovered Therefore they should be ignored (but not forgotten) when making decisions about the future Keep thinking on the margin: Continue to engage in an activity as long as the marginal benefit is greater than the marginal cost Question Answers: 8.1 = 2 8.2 = 2 & 4 8.3 = 3 8.4 = 3 8.5 = 3 8.6 = 2 8.7 = 1 8.8 = 2