Power Point - Department of Psychology

advertisement

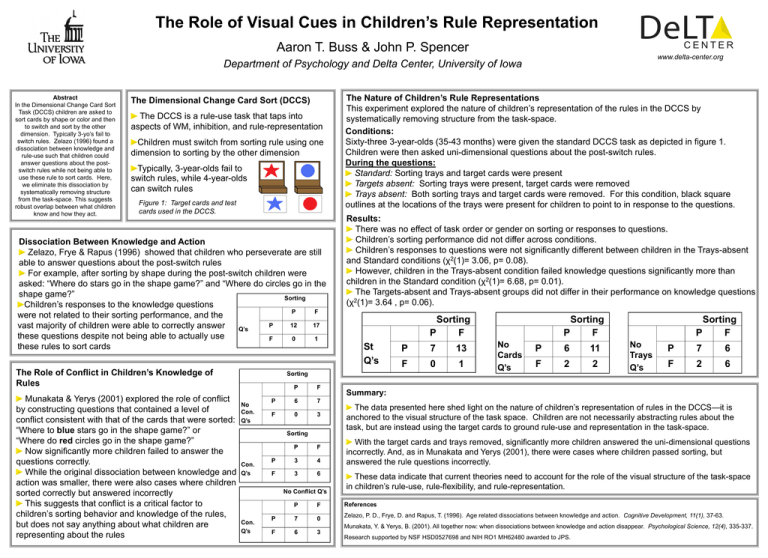

The Role of Visual Cues in Children’s Rule Representation Aaron T. Buss & John P. Spencer www.delta-center.org Department of Psychology and Delta Center, University of Iowa Abstract In the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task (DCCS) children are asked to sort cards by shape or color and then to switch and sort by the other dimension. Typically 3-yo’s fail to switch rules. Zelazo (1996) found a dissociation between knowledge and rule-use such that children could answer questions about the postswitch rules while not being able to use these rule to sort cards. Here, we eliminate this dissociation by systematically removing structure from the task-space. This suggests robust overlap between what children know and how they act. The Dimensional Change Card Sort (DCCS) The DCCS is a rule-use task that taps into aspects of WM, inhibition, and rule-representation Children must switch from sorting rule using one dimension to sorting by the other dimension Typically, 3-year-olds fail to switch rules, while 4-year-olds can switch rules Figure 1: Target cards and test cards used in the DCCS. Dissociation Between Knowledge and Action Zelazo, Frye & Rapus (1996) showed that children who perseverate are still able to answer questions about the post-switch rules For example, after sorting by shape during the post-switch children were asked: “Where do stars go in the shape game?” and “Where do circles go in the shape game?” Sorting Children’s responses to the knowledge questions P F were not related to their sorting performance, and the P 12 17 vast majority of children were able to correctly answer Q’s these questions despite not being able to actually use F 0 1 these rules to sort cards The Role of Conflict in Children’s Knowledge of Rules Munakata & Yerys (2001) explored the role of conflict by constructing questions that contained a level of conflict consistent with that of the cards that were sorted: “Where to blue stars go in the shape game?” or “Where do red circles go in the shape game?” Now significantly more children failed to answer the questions correctly. While the original dissociation between knowledge and action was smaller, there were also cases where children sorted correctly but answered incorrectly This suggests that conflict is a critical factor to children’s sorting behavior and knowledge of the rules, but does not say anything about what children are representing about the rules The Nature of Children’s Rule Representations This experiment explored the nature of children’s representation of the rules in the DCCS by systematically removing structure from the task-space. Conditions: Sixty-three 3-year-olds (35-43 months) were given the standard DCCS task as depicted in figure 1. Children were then asked uni-dimensional questions about the post-switch rules. During the questions: Standard: Sorting trays and target cards were present Targets absent: Sorting trays were present, target cards were removed Trays absent: Both sorting trays and target cards were removed. For this condition, black square outlines at the locations of the trays were present for children to point to in response to the questions. Results: There was no effect of task order or gender on sorting or responses to questions. Children’s sorting performance did not differ across conditions. Children’s responses to questions were not significantly different between children in the Trays-absent and Standard conditions (χ2(1)= 3.06, p= 0.08). However, children in the Trays-absent condition failed knowledge questions significantly more than children in the Standard condition (χ2(1)= 6.68, p= 0.01). The Targets-absent and Trays-absent groups did not differ in their performance on knowledge questions (χ2(1)= 3.64 , p= 0.06). Sorting P F St Q’s Sorting No Con. Q’s P F P 6 7 F 0 3 Sorting Con. Q’s P F P 3 4 F 3 6 No Conflict Q’s Con. Q’s P P F 7 0 P 7 13 F 0 1 Sorting P F No Cards Q’s P 6 11 F 2 2 Sorting P F No Trays Q’s P 7 6 F 2 6 Summary: The data presented here shed light on the nature of children’s representation of rules in the DCCS—it is anchored to the visual structure of the task space. Children are not necessarily abstracting rules about the task, but are instead using the target cards to ground rule-use and representation in the task-space. With the target cards and trays removed, significantly more children answered the uni-dimensional questions incorrectly. And, as in Munakata and Yerys (2001), there were cases where children passed sorting, but answered the rule questions incorrectly. These data indicate that current theories need to account for the role of the visual structure of the task-space in children’s rule-use, rule-flexibility, and rule-representation. References Zelazo, P. D., Frye, D. and Rapus, T. (1996). Age related dissociations between knowledge and action. Cognitive Development, 11(1), 37-63. Munakata, Y. & Yerys, B. (2001). All together now: when dissociations between knowledge and action disappear. Psychological Science, 12(4), 335-337. F 6 3 Research supported by NSF HSD0527698 and NIH RO1 MH62480 awarded to JPS.