Unit 7 B - National Union of Teachers

advertisement

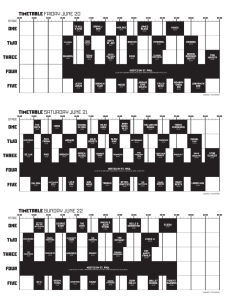

Part 2 Introducing the New Curriculum © Curriculum Foundation 1 a. Leading and managing change There is no shortage of models for the leadership and management of organisational change but, for the purposes of this programme, there is no need to consider the relative merits of different models. John Kotter’s 8 Step Process has been widely used by organisations from the US military to the English National Strategies! 2 Leading Change: John Kotter’s 8 Step Process You are here 3 Strategies for Change These last two units of the Year of the Curriculum programme relate to the final stage, ‘Implementing and Sustaining Change’, the last two of Kotter’s eight steps. Looking back at the previous six steps, it is striking that the process schools in England have followed has necessarily been rushed, with inevitable consequences for thoroughness and attention to detail. Hence there is a need for schools to be all the more careful to ensure the effectiveness of the implementation stage. Kotter’s heading for Step 7 ‘Do not let up’, is an excellent maxim for implementation, and his subsections of this step are: • Plan for and create visible performance improvements • Recognise and reward personnel involved in the improvements • Reinforce the behaviours that have led to the improvements In this unit we shall focus both on these key generic strategies for successful implementation and on specific strategies and issues relating to the curriculum. 4 b. Practicalities and considerations Phasing Once you have designed a new curriculum which is so much better than the one it is to replace, it is natural to be impatient to implement it so that students will benefit as soon as possible. However, the detail of the implementation strategy must wait until decisions have been made about phasing. Any major re-design is likely to involve some shuffling so that certain topics are taught earlier or later than they were. In these circumstances, to avoid some students missing key learning and repeating other topics, ‘big bang’ implementation is inappropriate. So a sensible approach is to phase implementation, often starting with year groups at the beginning of a Key Stage. The next four slides all relate specifically to the National Curriculum in England. Colleagues from other countries may wish to go directly to slide 29. 5 Implementing the NC in England The new National Curriculum in England must be implemented in maintained schools (which are not academies or free schools) in September 2014 ‘for the majority of year groups’. The Framework explains: ‘For pupils in year 2, year 6 and year 10, the new English, mathematics and science programmes of study will be introduced from September 2015; and for pupils in year 11 the programmes of study for these subjects will be introduced from September 2016.’ So phased implementation of the new curriculum is intended but what does this mean in practice? 6 Implementing the NC in England Year Group Year of Implementation English, Maths & Science 1 2014 2 2015 3 2014 4 2014 5 2014 6 2015 7 2014 8 2014 9 2014 10 2015 11 2016 So the guidance suggests implementation should be phased (or not), as follows: Key Stage 1 Lower KS2 Upper KS2 Key Stage 3 Key Stage 4 Yes No* Yes No* Yes Where ‘big bang’* implementation is required, particular care will have to be taken to ensure nothing is lost or repeated as described in slide 24. However there is some ‘wriggle room’. 7 Implementing the NC in England Under the heading ‘School Curriculum’ the guidance for the ‘core’ subjects - English, Maths and Science states that, although the programmes of study are set out year-by-year for key stages 1 and 2 (two yearly in English at KS2), schools are only required to teach the relevant programme of study by the end of the key stage. So schools have the flexibility to introduce content earlier or later within each key stage than set out in the programme of study. There is also the freedom to introduce key stage content during an earlier key stage, if appropriate. Hence what appears to be a rigid, year by year approach actually allows considerable freedom to juggle topics within and across key stages. How can this wriggle room be used creatively as the new curriculum is being implemented to avoid the pitfalls of gaps and repetition? 8 Implementing the NC in England All the content of the previous three slides has referred specifically to English, maths and science. The level of detail in the programmes of study of foundation subjects does not compare and some are very thin indeed. All are set out by key stage. Hence there is considerable scope for teachers to use their own judgement in shaping the curriculum in these subjects. There is no indication of whether the introduction of the new curriculum in these subjects should be phased. The best rationale to adopt in these circumstances must be to do what is in the best interests of learners. There are some particularly significant changes to be taken into account when designing the new curriculum including the switch from ICT to computing, the inclusion of cooking and nutrition in DT, the requirement for languages to be taught in key stage 2, the shift of emphasis in secondary languages and the changes to citizenship. The Framework for the National Curriculum for Key Stages 1 to 4 is available via the DfE website. Please click. 9 Phasing and flexibility The task of re-writing long, medium and short-term plans for a whole subject or year group is time-consuming and can be daunting. However, they do not all have to be complete before day 1 of the new curriculum. In fact it makes sense to stagger the work so that later plans reflect lessons learned along the way. Where implementation is to be phased (see slide 24 onwards), the task can be staggered over a longer period. A key feature of the new curriculum is that it must evolve and adapt in line with our rapidly changing world. One of the reasons for the urgent need for the current review now is the slow pace of curriculum change over several decades. This should be borne in mind as learning plans are re-written. The curriculum must not be set in stone! Obviously, a substantial proportion of the learning plans must be written in time for the new curriculum to be introduced. 10 Activity 3 • You have developed new planning templates. How will they be implemented? Which year groups will start when? • How regularly will you review and update the curriculum? 11 The timetable is too often cited as an insurmountable barrier to change (more so in secondary than primary schools). When a school has committed so much time and energy to curriculum redesign, with a vision of the potential impact on learners’ outcomes, it would clearly be a travesty for the timetable to stand in the way of progress. The timetable ‘tail’ should never be allowed to wag the curriculum ‘dog’. A comprehensive curriculum review provides an opportunity for a re-think of some long-established but hard to justify norms such as the metronomic timetable with all subjects being taught in identical chunks of time or withdrawal of pupils who are struggling to keep up into ‘catch up’ classes where the pace is slower. Schools will have to monitor carefully how well the timetable serves learning in the new curriculum and ask searching questions about what needs to change. It makes sense to scrutinise and rethink the timetable at a time of change. If it is postponed, it may never happen. 12 Getting the balance right If you have followed the design process in this programme you will no doubt have built your curriculum on the principle that it is so much more than subjects. Obviously it is essential this key principle is not watered down at the implementation stage. Most of the English framework consists of subject programmes of study but tucked away in section 2.2 at the start are two sentences with powerful implications but which could easily be overlooked…. 13 Getting the balance right School Curriculum 2.2 The school curriculum comprises all the learning and other experiences that each school plans for its pupils. The national curriculum forms one part of the school curriculum. National Curriculum An over-loaded curriculum is a familiar problem in many countries 14 Curriculum Inflation We considered the issue of the distinction between the school curriculum and the national curriculum in unit 1 and your design should have ensured that the balance is right with enough time devoted to the former. Schools have suffered from creeping curriculum inflation for generations as additions always seem to far outweigh content reduction. Implementation is clearly a key time for ensuring school curriculum priorities are firmly established and routinely reflected in practice. The principle of overload avoidance has to be clear at the outset and curriculum inflation has to be guarded against in future revisions. How will you achieve this? How will you build in checks and balances? 15 c. Securing Commitment and Quality If you have taken a collaborative approach to curriculum development and design, much of the work of securing the commitment of the staff team will already be done. A significant advantage in securing commitment is the fact that teachers have a natural affinity with a learner-centred curriculum. The vast majority of teachers were motivated to join the profession by ideals relating to giving young people the best start in life rather than putting them through an endurance test. ‘Preparing learners for the test of life and not a life of tests’ Ministry of Education, Singapore As Kotter suggests, recognising and rewarding personnel involved in the improvements will be important in securing continuing commitment. As this curriculum change is (for most) a school-wide paradigm shift, the strategy must draw in and reward all colleagues for their engagement and ensure all contribute to ongoing improvements. 16 A Win-win curriculum We can be confident that, as long as it is implemented effectively, the new curriculum with its relentless focus on deep learning will ultimately lead to improved outcomes for our young people. However, the wait for the ‘deferred gratification’ of national test outcomes means that schools need to generate interim ‘visible rewards’ that will regularly provide motivation and energise teachers and learners to strive for continuing improvement. There are many potential strategies schools could adopt for doing this. It would clearly be sensible both to accentuate the positive in terms of learning gains (reinforcing the behaviours that have led to the improvement) and, at the same time, as with any new initiative, to ensure that feedback is used to improve effectiveness and drive improvement. In this way, a virtuous circle is created and the ‘win win’ nature of the new curriculum can be secured. Strategies for further improvement Improved motivation Improved curriculum Visible improvements to learning 17 Monitoring for quality and Impact The previous slide related to what might be described as ‘cheerleader’ monitoring: strategically looking for the positive and using it to strengthen the team ethos and boost the impetus for change. However, all schools have existing monitoring systems and these must be adapted to align with the new curriculum aims. As with all the school’s other systems, monitoring of teaching and learning must support the change the school is trying to bring about. This monitoring will provide the evidence of both what is working well and areas for improvement and hence will inform improvement strategies as new practice develops. Schools have developed considerable expertise in monitoring to ensure that all groups of young people are well served and that none are disadvantaged. With such major change to the curriculum, it will be important to explore whether any such unforeseen issues arise that need to be addressed. 18 Professional Development As with every new initiative, it is essential that professionals have access to appropriate, high quality development and training if they are to optimise their performance as leaders of learning of the new curriculum. The pedagogy associated with the new curriculum may require teachers to adapt their practice, particularly those whose training and experience has been more focused upon traditional teacher-led approaches. In the early stages of implementation there will clearly be a need for whole staff CPD to address the challenges associated with teaching and learning of skills, attitudes and competencies and using these to accelerate progress in terms of knowledge. As experience grows and feedback from routine monitoring provides valuable evidence, CPD can be tailored to target identified areas of need. 19