Funding Schools: What Pennsylvania Can Learn From Other States

advertisement

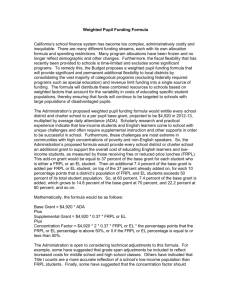

Funding Schools: What Pennsylvania Can Learn From Other States ROB KNOEPPEL CLEMSON UNIVERSITY Goals of Education Finance Distribution Systems Accounting for differences in the costs of achieving equal educational opportunity across schools and districts. Accounting for differences in the ability of local public school districts to cover those costs. State Education Finance Survey Three questions guided the development of the survey: How do states pay for public elementary and secondary schools? What are the key methods they use? How are special needs supported? Key Methods for Funding Public Education Foundation Programs (37 states)—Provides a uniform state guarantee per pupil, with state and local district funding. District Power Equalization Systems (2 states)—Provides funding that varies based on tax rates. Full State Funding (1 state)—All funding is collected and distributed by the state. Flat Grants (1 state)—Provides a uniform amount per pupil from state funds; localities can add funding to this amount. Combination Systems (9 states)—These combine several funding plans (listed earlier). School Finance Formulae by State Foundation Program (37) AK, AL, AZ, AR, CA, CT, CO, DE, FL, ID, IN, IA, KS, ME, MA, MI, MN, MS, MO, NE, NV, NH, NJ, NM, NY, ND, OH, OR, PA, RI, SC, SD, TN, VA, WA, WV, WY VT, WI District Power Equalization (2) Full State HI Funding (1) Flat Grants (1) NC Combination GA, IL, KY, LA, MT, MD, OK, TX, UT Approach (9) Foundation Programs In a foundation, the state sets a guarantee of funding per pupil. Localities contribute to the foundation with a defined uniform tax rate through a percentage based on local ability to pay. The local contribution is typically generated through the property tax. State aid is the difference between the foundation and the local contribution; this is known as equalization. Foundation Considerations State Guarantee Amount Local Contribution Allocation Unit Wide variation in the base student amount Either a required tax or a percentage of the foundation Student Units – either ADA, ADM, WPU Based on notions of equity or adequacy South Carolina = minimally adequate Maine = adequacy based Missouri = adequacy target SC - $1630 in 2011; AZ $3267 in WPU in 2011; AR $6023 in ADM in 2011; PA $8950 in 2011 Teacher Allocation (Alabama, Tennessee) District Power Equalization The focus here is taxpayer equity in the form of equal yield. In DPE, a uniform tax base is set for the entire state and localities are permitted to determine the tax rate. The local contribution is equal to the tax rate multiplied by the local tax base. State aid is calculated to be the difference between the yield of the guaranteed tax base and the local yield. These systems are quickly becoming obsolete likely because they permit different funding across districts. Other Funding Mechanisms In full state funding, the state distributes the entire cost of education to each district. Local funds are not part of the funding formula although local contributions are permitted. Flat grants were originally used by states as a means of providing assistance to districts but have been abandoned because they provide low levels of aid and create inequities. Considerations When Choosing a Funding Formula The key issue related to the funding formula in each respective state appears to be whether the focus is on equity or adequacy. Does the funding formula provide equal opportunity for all students to learn regardless of circumstance? Is the funding sufficient to teach all children to established standards? Further, the definition of the adequacy target is of importance. Is it a minimum standard? Is it a quality education? The determination of the basic aid is of importance; states appear to be moving toward the use of a rational basis of determining the base student cost rather than relying on residual budgeting. Student Need and District Characteristics Adjustments have been made to the base student cost to acknowledge the additional costs of providing equality of educational opportunity. These include: Enrollment Geography Labor market characteristics Student demographics These adjustments are made in the form of weights; they may also be done through the use of categorical aid. Measuring Equity Scholars have used multiple methods to determine the equity of finance formulae Range Coefficient of Variance McLoone Index Verstegen Index It is generally accepted that state education distribution models that include a greater percentage of aid that is distributed by the state are more equitable; those systems are less reliant on local measures of wealth. Variation that is attributed to differences in student need has been termed “the right kind of inequity.” More recently, the focus of equity studies are focused on the alignment of resources and resource allocation patterns with measures of student achievement – equal outcomes. The primary area of focus is sufficiency of resources. Summary A total of 46 states use a foundation program or a foundation program coupled with another funding mechanism. The trend is an increase in adjustments to the foundation to pay for high cost students; these adjustments are made through weighted funding, categorical aid, or block grants. The range in funding is largely seen based on the goal of the system – equity or adequacy. More states are beginning to use a rational basis formula to determine the cost of the foundation. Issues to Consider: Stable Source of Revenue The ability to budget (and therefore provide a system of public education) is contingent upon a stable source of revenue. Economists have estimated that the elasticity of a tax must be equal or greater to 1 to provide a stable source of revenue for education. Kent and Sowards (2009) and McGuire and Papke (2008) have estimated that property taxes account for over 80 percent of all local sources of revenue for public schools. Despite the historical reliance on this revenue source to fund education and other services, the property tax is perhaps the most unpopular tax in the United States. According to Dornfest (2003), “the public continues to express resentment toward this tax and politically empowered groups whittle it away through demand for exemption or other favored treatment” (p. 34). Revenue Stability: Lessons from South Carolina Passed in 2006, Act 388 exempted owner-occupied residential property from school operating taxes beginning in tax year 2007; Concurrently, the state sales tax was increased from 5% to 6%. Revenue from the increased sales tax was placed in a Homestead Fund and was dedicated to offset lost property taxes and paid to school districts; School districts received additional state aid from the Homestead Fund beginning in fiscal year 2007-2008. Coincided with the financial crisis of 2007-09. The only tax revenue that matched projections was property tax; the only tax with an elasticity of at least 1 was the property tax. Resulted in cuts to education in the base student cost of over one-third. Issues to Consider: Hold Harmless Hold harmless provisions take many forms: Ceilings and Floors to changes in the foundation amount Allocations to schools with declining enrollments Use of past enrollment for the foundation amount The basic premise is that no district should receive either less state aid or less in total funding than it received in some baseline comparison year. Nearly every state has a hold harmless provision. Multiple scholars have postulated that hold harmless provisions can have the unintended consequence of increasing inequity in funding distribution models, especially if these allocations are not made based on a rational cost basis. Hold Harmless: Lessons from Indiana, Rhode Island, Illinois, and Mississippi “What many may not recognize is the degree to which hold-harmless provisions lock-in past aid distributions and create current aid distributions that differ dramatically from those that would result from literal application of aid formulae” (Downes & Pogue, 2002). The literature suggests that phasing out hold harmless provisions gives districts the opportunity to adjust to funding cuts. Hold Harmless provisions hurt districts when the decline in marginal revenues exceeds the decline in marginal costs – (Indiana Study 2007). Rhode Island (10 years) and Illinois (10 to 12 years) have adopted plans to phase out hold harmless provisions. Mississippi has adopted a 4 year phase out plan as they implement a new formula based on adequacy. Issues to Consider: Funding to Charters A variety of funding models exist to support charter schools across the states and the District of Columbia; in general, the funding is similar to that of public schools where there is a local and a state share paid. Three strategies for funding charters exist: Per pupil revenues based on the district where the child resides; under this provision, the district passes on a portion of the funding for students – Used in 8 states Per pupil revenues based on the authorizers’ districts – similar to the previous, but the per pupil revenue is based on the district where the charter is located – used in 29 states A state charter per pupil allocation – 5 states and the District of Columbia. The main question is what level of funding should a charter receive as compared to a traditional school. Not much research exists on this, but a recent study (2014) reveals that, on average, charters receive 19 percent less than traditional schools; this equaled $2,247 per pupil. Charter School Funding: Lessons from Massachusetts Possible reasons for decreased charter funding include: Fixed district costs cannot be transferred to a charter – for example building costs Schools have differential funding based on student need Charter schools may not provide costly services such as special education, lunch, and transportation. Massachusetts includes a hold harmless provision for charter schools that is phased out over a six year period. Research is sparse on funding requirements for charter schools. Concluding Thoughts The funding formula needs to be based on a rational cost basis and allocated based on student units and linked to student performance goals. Some states, such as Virginia and Tennessee, have articulated resources that must be included in schools. In Virginia, these resources are called The Standards of Quality. They include items such as student-teacher ratio, number of administrators, number of school counselors, length of the school day, length of the school year, computers, books in the library, etc. There is a regional cost to the Standards of Quality – that serves as the foundation amount for the state. In Tennessee, state funding is tied to teacher allocations based on specified student-teacher ratios. A provision to re-examine the cost of the foundation over time is used in Georgia.