Unit 3 PPT - Coeur d`Alene School District

advertisement

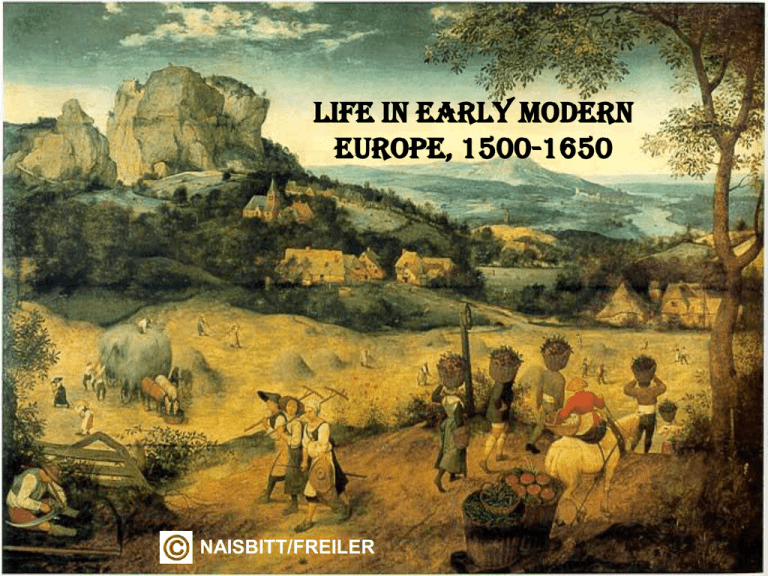

LIFE IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE, 1500-1650 NAISBITT/FREILER INTRO: SETTING THE SCENE • The scene of communal farming is repeated with little variation throughout Europe in the early modern era • With one bed per household, the family was obviously close-knit • There was no running water, no central heat, no bathrooms, and no electricity • A 16th century prince endured greater material hardship than a 20th century welfare recipient • The whole family performed physical labor reminding us that the life of the ordinary people of the early modern era was not romantic EUROPEANS SHARED EXPERIENCES • While there was no typical 16th century European, there were shared experiences • Agriculture increased as more land was cleared and more crops were grown • The century-long population explosion and increase in commodity prices fundamentally altered lives RURAL LIFE THE NORM • In the early modern era, as much as 90% of the European population lived on farms or in small towns where farming was the principal occupation • Villages were small and isolated • They ranged in size from 20-100 families • The village was the bedrock of the 16th century state • The manor, the parish and the rural administrative district were the institutional frameworks PEASANT BUDGET • Manorial rents supported the lifestyle of the nobility; parish tithes supported the Church; local taxes supported the power of the state • Rents, tithes, and taxes absorbed more than half of the wealth produced by the peasant • From the remaining half, the peasant had to make provisions for the present and future Tithes SURVIVAL • To survive, the village had to be self-sufficient • Hard times meant hunger and starvation – both of which were accepted as part of the natural order • One in three harvests was bad; one in five was disastrous • Depending on the soil and crop, between one-fifth and one-half of the grain harvested had to saved as seed for the next year HOUSING • Hunger and cold were constant companions of the average European • Especially in Scandinavia and Muscovy, winter posed as great a threat as starvation • Most homes were made of wood and roofed in thatch • Walls were patched with dry mud and the ground was leaves or straw • The typical home was one large room with a hearth at one end Thatched homes HOME FURNISHINGS • People had few household possessions • The essential piece of furniture was the wooden chest, which was used for storage • A typical family could keep all their possessions in the chest, which could then be buried or carried away in times of danger • The chest could also be used as a table or bench • Most domestic activities, including cooking, eating and sleeping, took place close to the ground, thus sitting, squatting, and kneeling were the usual positions • Most family possessions related to food production • Iron spits and pots were treasured possessions • Most kitchen items were made of wood, including long-handled spoons, trenchers (boards for cutting and eating), cups and bowls • Knives were essential but forks were still a curiosity THE KITCHEN ? ISOLATION For many Europeans, the village was where they were born, lived, and died • Up at dawn, asleep at dusk; long working hours in summer, short ones in winter • For most, the world was bounded by the distance that could be traveled only by foot • Most died never seeing more than a hundred other people or hearing anything louder than a human voice or thunder • Their wisdom was based solely on experience AGRICULTURE – THE PLAINS • Peasant life centered on agriculture • While technology and technique varied little across the continent, there were significant differences depending on climate, soil and the animals they raised • Across the great plain (Low Countries to Poland) the three-crop rotation was the norm • Grain composed 75% of the calories of a typical diet • 1) Winter- wheat • 2) Spring – barley, peas, beans • 3) Fallow (idle) More than 80% of crops grown were consumed on the farm AGRICULTURE – THE MED Olive trees are everywhere in the Mediterranean • The warm and dry climate of the Mediterranean favored a two-crop rotation • With less water and stronger sunlight, half the land had to be left fallow each year to restore the nutrients • Grapes and olives were staple crops as meat was less plentiful AGRICULTURE – THE MOUNTAINS • The mountainous and hilly regions of Europe depended on animal husbandry for subsistence • Sheep were the most common animal raised by Europeans • Sheep provided the raw material for most clothing, their skin was used for parchment and window covers and they were an inexpensive source of meat • Pigs were domesticated in the woodland regions • Cattle were largely “farm animals” utilized most extensively in Hungary and Bohemia LAND – KEY RESOURCE • Because agriculture was the principal occupation of Europeans, land was the principal resource • Most land was owned by lords who rented it out in various ways • The land was divided into manors, and the manor lord, or seigneur, was responsible for maintaining order, justice, and arbitrating disputes THE MANOR • On a manor there was a village, church, lord's house or castle, and the farmland upon which the people worked • The peasants had requirements they had to fulfill in order to live there which involved farming the lord's land and paying rents with food PEASANTS AND THE LAND • In western Europe, peasants generally owned between one-third and one-half of the land they worked • In eastern Europe peasants owned little if any land • In return for rent, peasants used the land as they saw fit and could hand it down to their children • While rent payment in the form of coin occurred, most often the lord received a fixed amount of the crop yield or labor (labor service called the robot in eastern Europe and the corvee in France) • German and Hungarian peasants owed 2-3 days per week, while Polish peasants owed as much as 4 days of labor FARM WORK • Farm work was ceaseless toil • The draught animals were critical elements of any farm and the birth of foals and calves were celebrated more than the birth of a child and the death of an ox or horse was a catastrophe THE RHYTHM OF THE DAY • Men and women worked to the natural rhythm of the day • Up at dawn, at work in the cooler hours, at rest in the hotter hours • Rain kept them idle, sun busy • In the summer the laborers met at 4 a.m. and in the winter 7a.m. • Wages were paid by the hours worked: 7 in winter and as many as 16 in the summer GUILDS ORGANIZE LABOR • In all towns there was an official guild structure that organized and regulated labor • Rules laid down the requirements for training, standards for quality, and the conditions for exchange • Only those officially sanctioned could work in trades, and each trade could perform only specific tasks ACUTE POVERTY • Urban poverty was endemic and grew worse as the century wore on • In most towns, as much as a quarter of the entire population might by destitute, living on day labor, charity, or crime • In the countryside conditions could be worse as no formal agencies for relief existed • The urban poor more often suffered from disease than starvation LARGE TOWN VS. SMALL TOWN • In larger towns a greater variety of occupations and a greater reliance of wage earnings set it apart from smaller towns • Occupations were usually organized geographically, with metal or glass working in one quarter of town, brewing or baking in another • There was a strong family and kin network to the occupations, which were handed down from parents to children WOMEN’S OCCUPATIONS • Women in larger towns had more job options than their country counterparts • Being mid-wives or nurses were two options available to women in larger towns • Prostitution was officially sanctioned in most large towns in the modern era • Brothels were subject to taxation and governmental control MAJORITY: UNSKILLED LABORERS • Most town dwellers were unskilled laborers • Day laborers, hauling or lifting goods on carts or boats, stacking materials at building sites, or delivering food or water were the main day-laboring jobs • As the century progressed the number of laborers exceeded the number of jobs and many sought servant jobs DOMESTIC LABOR • Domestic labor was a critical source of household labor • Even those families of marginal means employed servants to help in the numerous household tasks • Commonly, household servants did not advance in status and frequently changed employers in hope of better conditions IMPORTING GRAIN • Towns often survived by importing grain from rural communities • All towns had municipal storehouses of grain to preserve their inhabitants in time of famine • Grain prices were strictly regulated and subsidized • The average laborer’s diet consisted of meat, soup, vegetables, wine and beer th 16 CENTURY POPULATION INCREASE • During the 16th century, the European population increased by about a third (from 80 million to 105 million) • Western European growth was especially significant in the first half of the century while eastern European growth was steady throughout the century • Europe had finally recovered from the plague and by 1600 its population was at a high point • Fifteen cities more than doubled their populations, with London increasing 400% EFFECT OF POPULATION GROWTH - POSITIVE • Early in the century, the growth brought prosperity as the land was not farmed to capacity, and the extra hands increased production • As the rural areas filed the spillover went to small towns and cities Initially, land was available in the early 16th century EFFECT OF POPULATION GROWTH - NEGATIVE • There is a natural limit to the number of people that could profit from a given industry, and by midcentury Europeans were experiencing saturation in many industries • Most apprenticeships were limited and guilds enforced restrictions on new entrants • By mid-century a glut in the workforce forced real wages (purchasing power) to fall PRICE REVOLUTION • The fall of real wages took place during a period of inflation known as the Price Revolution • For example, between 1500-1650 cereal prices increased 5 times and manufactured goods doubled in price • Most of the increase took place in the second half of the 16th century as a result of population increase and the import of gold and silver from the New World • The Price Revolution impacted government finances and trade throughout the continent IMPACT OF PRICE REVOLUTION • As a result of the steep rise in prices, some people became destitute; others became rich • Towns were especially hard hit due to the enormous increase in grain • Those who grew their own food were more insulated from the effects, while those who counted on their subsistence from labor were in greater peril CYCLE NOW TURNS VICIOUS • Those who had sold and left their land to seek prosperity in towns were forced to return to the land as agrarian laborers • In western Europe, they became landless poor, seasonal migrants without the safety net of communal living – by 1600 many were starving • In eastern Europe, the landed nobility solidified their position SOCIAL LIFE • In the early modern era, the group rather than the individual was the predominant unit in society • The first level of the social order was the family and the household • Next, was the village or town community • Finally, the gradations of ranks in society at large; each group had its own place and performed its own functions HIERARCHY • Hierarchy was the dominant principle of social organization in the early modern era • Hierarchy at every level existed; lords & commoners, master & apprentice, government official & citizen, landholder & landless, husband & wife, parent & child SOCIAL STATUS • Status, not wealth, determined hierarchy in society • Status was apparent everywhere • It involved bowing and hat doffing, clothing, and food • Status was significant in titles including nobles, goodmen and goodwives, squires, and ladies • The acceptance of status was an uncomplicated, unreflective act, similar to stopping at a red light • Inequality was a fact of European social life that was unquestioned GREAT CHAIN OF BEING • To reinforce the social hierarchy, images such as The Great Chain of Being were perpetuated • The Great Chain of Being was a description of the universe in which everything had a place, from God to rocks THE BODY POLITIC • Another metaphor used to reinforce societal hierarchy was the idea of the Body Politic • In this “body” the head ruled, the arms protected, the stomach nourished, and the feet labored • The image depicted a small community as well as a large state • The king was the head, the Church the soul, the nobles the arms, the artisans the hands, and the peasants the feet • Each performed its own vital function • Both the Great Chain and the Body Politic were conservative concepts of social organization designed to maintain the status quo NOBLES Arms of Hughes of Tipperary • Nobility was a legal status that conferred certain privileges to its holders • Rank and title provided a well-defined place at the top of the social order that was passed from generation to generation • The escutcheon – coat of arms – was a universally recognized symbol of rank and family connection whether you were a prince, duke, earl, count, or baron POLITICAL CLOUT • Among the most important privileges held by nobles involved political influence • In most countries the highest offices of the state and military were reserved for members of the nobility • In Europe, various diets and political bodies were often composed strictly of nobles ECONOMIC CLOUT • Additionally, nobles enjoyed economic privileges as a result of their rank and role as lords of their land • In almost every nation, nobles were exempt from taxation • The nobles of eastern and central Europe benefited greatly from these exemptions MILITARY OBLIGATIONS • Initially, nobles were considered a warrior class that was expected to raise, equip, and lead troops into battle • By the 16th century, military needs of the state surpassed the nobles ability to provide it • Warfare had become a national enterprise that required central coordination • Nobles had become administrators as a new “service” nobility emerged GOVERNMENT OBLIGATIONS • Nobles also had the obligation of governing at both the local and national level • At the discretion of the ruler, a noble could be called upon to engage in any governmental occupation • Additionally, they expected to provide for the needy and maintain good relationships with the peasants that worked their land THE TOWN ELITE The urban elite was largely a western European phenomenon • Over the course of the 16th century, a new urban elite emerged • They enjoyed many of the same political and economic privileges of the rural nobles • However, many members of this new social class were caught between the nobles and the commoners – despised from above and envied from below THE GENTRY • As the century progressed the accumulation of large estates by non-nobles increased • They received rents and dues, administered their estates, and provided for their peasants – all without the traditional “rank” • In England, the group came to be known as the gentry, and there were parallel groups in Spain, France and the Empire In England, the gentry had the right to a coat of arms and could be knighted, but the position was not hereditary and the gentry could not belong to the House of Lords CITIZENS VS. NON-CITIZENS • The order of rank below the town elite, pertained to the type of work that one performed • Citizenship was restricted to membership in certain occupations and guilds • While it could be purchased, most citizenship status was earned through mastering a profession after a period of apprenticeship • Only males could become citizens The New Rich: • During the early modern period, traditional social hierarchy changed • Why? Population increase meant more governors to perform military, political and social functions of the state • Second, opportunities to accumulate wealth increased dramatically during the Price Revolution – individuals could rapidly increase their economic position via gold, silver, or selling commodities • Profits from state service (tax collection, officeholding, law) proved lucrative, too TRANSFORMATION OF THE TRADITIONAL SOCIAL HIERARCHY TRANSFORMATION OF THE TRADITIONAL SOCIAL HIERARCHY Beggars soon became separated into the “deserving poor” and the so-called “sturdy beggars” The New Poor: • Social change was equally apparent at the bottom of the social scale • Population increase created a group of landless poor who squatted in villages and clogged the streets of towns and cities • As many as one in four Europeans were destitute • Traditionally, local communities (especially the Church) cared for the poor • As the century progressed, local efforts at poor relief were overwhelmed by the sheer numbers of needy • Crime increased throughout the modern era as well PEASANT REVOLT • One consequence of the economic and social changes of the 16th century was an increase in violent confrontations between peasants and their lords • Most revolts involved peasant leaders, petitions, and an organized rank and file with moderate political demands • Peasant revolts were viewed as such a threat to social order that they were put down with the severest repression and brutally Peasant revolts were usually organized and well-planned, but always met with disaster GERMAN PEASANTS’ WAR • By far the most widespread peasant revolt of the 16th century, the German Peasants’ War involved tens of thousands of peasants and combined a series of agrarian grievances with an awareness of Luther’s new religious spirit • Although he had a large following among peasants, Luther advised them to passively accept their fate • The peasants disregarded his advice and organized large armies led by experienced soldiers AGRARIAN CHANGES Nobles wanted the forest for their wild game, while the peasants objected to the game eating their crops • Peasant frustration was not typically aimed at their lords, rather their anger was a product of agrarian changes brought on by population increase and market production • Many of the traditional rights and obligations of the lords and peasants gave way to the need for more land and crops • One important example was forest rights • As land became more scarce, lords and peasants battled over common forest land and wild game ENCLOSURES THREATEN TRADITION • Another conflict arose over the enclosure of crops • Enclosure meant a fence or hedge that separated one parcel of land from another • The enclosure movement destroyed the tradition of communal farming • It was yet another aspect of tradition losing out to economic progress (in this case private enclosed estate farming) • Enclosures were a source of resentment for the poorer peasants GERMAN PEASANTS CRUSHED • Some of the demands of the peasants included; a share of the woodlands, more freedom for the peasant (serf in some cases), stable rents fixed at fair rates, and a return to the ancient customs that had long governed lords and peasants • The demands of the peasants reflected a traditional order that no longer existed • They were caught between the jaws of an expanding state and a changing economy • More than 100,000 peasants were slaughtered during and after the war – the jaws had snapped shut PRIVATE AND COMMUNITY LIFE While the great events of the 16th century dominate the headlines, perhaps the key to understanding Europeans is to look at their family and community life • The great events of the 16th century (New World discovery, consolidation of states, increased ferocity of wars, religious reform) did impact the lives of the common European • However, the lives of most Europeans centered on births and deaths, the harvest, festivals, and social relations in the family and community • Their strongest loyalties were to family and community rather than church or state THE FAMILY • Sixteen-century life centered on the family • European families were primarily nuclear, especially in western Europe • In Hungary and Muscovy, for example, taxation was based on households and thus encouraged extended families • The concept of family and family lineage created a sense of stability and longevity in a world in which individual life was short FAMILY AS ECONOMIC UNIT Van Gogh’s take on a peasant couple going to work the field, 1890 • The family was also an economic unit; the basic unit for production, accumulation, and transmission of wealth • Every member of the family had his or her own functions that were essential • Tasks were divided by gender and age, but there was far more intermixture than is traditionally assumed FAMILY AS SOCIAL UNIT • The family was also the primary unit of social organization • In the family, children were educated and the social values of hierarchy and discipline were taught • At the top of the family was the father – the head of household who ruled his wife, children and servants • Next, the mother – who ruled the children who owed obedience to both parents • The wife also had authority over male apprentices FAMILY SIZE AND MARRIAGE AGE • Though the population was increasing, the typical family size remained at 3-4 children • Late marriages and breastfeeding helped control family size • Women married around age 25; men slightly later • A woman could expect about 15 fertile years and 78 pregnancies with 3-4 children surviving beyond age 10 Peasant Mother and Child by Mary Cassatt WOMEN IN THE ERA Breton Peasant Women by Paul Gauguin • Constant pregnancy and child care help explain some of the narrow gender roles of the era • Biblical injunctions and traditional stereotypes help explain others • The woman’s sphere was the household • On the farm she was in charge of food, domestic animals, children’s care and education, clothes • In towns, women supervised the shop that was part of the household, sold goods, kept accounts, and directed the work of apprentices MEN IN THE ERA • The man’s sphere was the public – the fields in rural areas, the streets in towns • Men plowed, planted, and did the heavy farming • They made and maintained the farm equipment, took charge of the large farm animals, and made farm purchases • Men attended court proceedings and other affairs of the village • Only men could be citizens of the towns, full members of most guilds, and participate in civic governments Man Smoking, Room XIII by Van Gogh 1888, oil on canvas Pieter Brueghel - Peasant (aka Village) Wedding Feast • On the farm, the community was the village; in the town, it was the ward, quarter, or parish • The community was not a idyllic haven of love and charity – violence and feuds were common on the farm or in the town • The community provided the culture and identity for the European LORD’S ROLE • The two basic forces in the rural community were the lord and the priest • The lord set the conditions for work and property arrangements • However, use of common lands, rotation of labor service, and the form in which rents were paid were all collective decisions made by village headmen and elders in conjunction with a lord’s agent PRIEST’S ROLE The priests served as a conduit for all the news of the community and the focal point for the village festive life • The parish priest or minister attended all the important events of life – birth, marriage, and death • The church was the only common building of the community; it was the only space not owned by the lord or an individual family • In rural communities the church was the only organization to which people belonged • Social ceremonies bound the community together • For example, the annual perambulation involved a walk around the village fields before planting began • The priest would lead the walk and then bless the fields • Individuals reaffirmed their shared identity through ceremonies like the perambulation WEDDINGS • The most common ceremony was the wedding • The wedding was a combination of a religious event and a community procession with feasting and festivity • The wedding was celebrated as the moment when the couple entered fully into the community • Parents were a central feature of the event as they approved the union and planned the dowry and inheritance PROPERTY AND WEDDINGS • Traditional weddings involved the formal transfer of property • The bridal dowry and the groom’s inheritance were formally exchanged during the wedding • The public procession – “the marriage in the streets” – was as important as the religious service • It was followed by a feast as abundant as the bride and groom could afford SEXUAL LEGITIMACY • Weddings also legitimated sexual relations • Many of the dances and ceremonies that followed the feast symbolized the sexual congress • Bridal beds were often passed from mothers to daughters • Consummation was a vital part of the wedding, for without it the union could be annulled • Finally, the wedding served to elevate the couple to full status as adults in the community SEASONAL FESTIVALS • In town and country, the year was divided by a number of festivals that defined the rhythm of toil and rest • They coincided with both agricultural life and the Christian calendar • Christmas and Easter were the two most widely observed Christian holidays • Carnival, which preceded Lent, was a rowdy series of feasts and parties • Others included, The Rites of May and All Hallows Eve Battle of Carnival and Lent, Brueghel, Pieter the Elder PURPOSE OF FESTIVALS • Festivals helped maintain the sense of community that might have been weakened during the long months of work • They were first and foremost celebrations in which feasting, dancing and play were central • But they also served as safety valves for the pressure and conflicts built up over the year • They served to reinforce social hierarchy and deference and community mores The stress of a bad harvest, famine or any number of other maladies, was released during the various festivals PUNISHMENT AND FESTIVALS • Festivals also served to publicly punish various offenders • For example, a promiscuous men or women by placing horns on their head • Or a man who had failed to control his wife might be force to ride backwards on a horse to symbolize the backwardness in the family • Such forms of community shaming rituals worked not only to punish offenders but also to reinforce the social and sexual values of a village as a whole • In this preliterate society, the people’s beliefs blended Christian teaching and folk wisdom with a strong strain of magic • Popular belief in magic was prevalent all over Europe and operated in much the same way as science does today • Only skilled practitioners could perform magic and they had their own language • Some focused on herbs and plants, others on diseases of the body MAGICAL BELIEFS Alchemists (above), worked with rocks and minerals, astrologers with the movement of stars PURPOSE OF MAGIC • The wealthy favored astrology and paid for advice on the best day to marry or invest • Poorer villagers sought the help of herbalists to help control the aches and pains of daily life • Sorcerers and wizards were called upon in more extreme situations such as bad harvest or matters of life and death VILLAGE MAGICIANS • Most village magicians were women because it was believed that women had the unique knowledge and understanding of the body and “magical” herbs • Magicians also advised the lovesick on potions and spells that would gain them the object of their desires • Magic was believed to have the power to alter nature, and it could be used for good or evil THE WITCH CRAZE • Magic for evil was black magic, or witchcraft • Witches were believed to possess special powers that put them in contact with the devil and the forces of evil • This belief in the presence of good and evil was Christian as well as magical • Beginning in the late 15th century, Church authorities began to prosecute large numbers of suspected witches • By the end of the 16th century there was a continentwide witchcraze WOMEN PERSECUTED • Unmarried or widowed women were usually targeted for persecution as witches (80%) • A fear of those not under male control was evident from the above figures • The sexual element of union between a women and a devil serves as one possible explanation • More likely, women’s unequal status in society played a larger role – they were an easy target • Misfortunes that occurred were blamed on the activities of witches Women’s role as healers led in part to their persecution WESTERN EUROPE: HOTBED FOR PERSECUTION • Because there was such widespread belief in the presence of diabolical spirits and in the capabilities of witches to control them, Protestant and Catholic church courts easily found witnesses to testify against suspected witches • Interestingly, Calvinist Scotland had more trials for witchcraft than Spain and France combined