apart2013_PART 1 OF 2 greek art short

advertisement

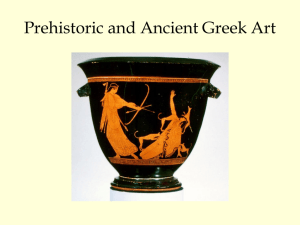

Dr. Schiller: AP History of Art PART 1 OF 2 Greek Art: Gods, Heroes, and Athletes Greek Art: 1200-30 BCE Periods Dark Period: Geometric Period: Orientalizing Period: Archaic Period: Severe Style: Classical Period: Late Classical Period: Hellenistic Period: Dates: 1200-800 BCE 800-700 BCE 700-600 BCE 600-480 BCE 480-450 BCE 450-400 BCE 400-325 BCE 325-30 BCE Greek Art: 1200-30 BCE • This chapter introduces you to the Greek world and its contribution to Western civilization. • For the Greeks the body was the visible means of conveying perfection • We’ll see the figure developed as: --a representation of the humanity of the Greeks --their attempt to gain perfection. • There are 3 big tenets of Greek art: 1. balance 2. harmony 3. symmetry. • These ideals are reflected in architecture as well as sculpture. Greek Art: 1200-30 BCE • A complication peculiar to the study of Greek art is that we have 3 separate and sometimes conflicting sources of information: 1. the works themselves 2. Roman copies of Greek works 3. literary sources Greece Chapter 4: THE RISE OF THE GREEKS, 1000-500 BCE: Introduction: Greece Since water was scarce, the Greeks used olive oil to clean themselves The Greek Dark Period •The Greek “Dark Age” was a period during which Greece and the whole Aegean region were largely isolated from the rest of the world •It began around 1200 BCE It ended around 800 BCE when Phoenician ships began to visit the Aegean Sea, reestablishing contact between Greek and the Middle East Phoenicia Greece Mediterranean Sea • Geometric Period: BCE 800-700 One of the major differences between this early period and its counterpart in the Ancient Near East (remember Assyrian art?) is the fascination the human body had for the Greeks Mesopotamian Greek Geometric Period: BCE 800-700 * Even in the 8th C. BCE, the Greeks were interested in the depiction of anatomy and detail natural movement * We know Geometric Style only from painted pottery and smallscale sculpture: --the two forms are intimately related --pottery was often adorned with figurines just like the forms from sculpture --sculpture was made of clay or bronze—probably learned metal-working from the Mycenaeans Geometric Sculpture • The figure of Hero and Centaur (Herakles and Nessos?) illustrates the sense of volume and natural movement. Stokstad plate 5-6 Hero and centaur (Herakles and Nessos?), ca. 750-730 BCE. Bronze approx. 4 ½ “ high. Geometric Sculpture • • • This bronze sculpture illustrates the anatomy, even though one figure is a mythic creature, centaur The artist represents both figures as naked. A more natural representation of the figures is presented by showing the curving of the anatomy Geometric Sculpture • Note the lower torsos of both figures depict a primitive attempt at showing the form (human figure). Geometric sculpture, continued • • The Greek artist has attempted to show the scene, thought to be the battle between Herakles and Nessos, by aligning the arms of both figures as if in a wrestling match. The elbows of both figures are cocked (i.e. bent) and tense as if in battle. Geometric sculpture, continued • Following the Herakles and Nessos, is the Mantiklos Apollo. [Gardner plate 5-3] Mantiklos Apollo, statuette of a youth dedicated by Mantiklos to Apollo, from Thebes, Greece, ca. 700-680 BCE. Bronze approx. 8“ high. Geometric sculpture, continued • • • • This work continues to illustrate the focus of the Geometric artist with an emphasis on human anatomy. The upper torso is showing more anatomical naturalism, from the shoulders to the stomach, the artist has been engaged in illustrating a more realistic presentation of the human male figure. This figure is naked as well. NOTE: Although some art historians put this work in the Geometric Period, Gardner puts this work in the Orientalizing Period; its pretty much on the cusp between Geometric and Orientalizing • • Geometric art The Geometric artist did not confine his work to the threedimensional medium alone. Greek Dipylon Vase painting reflects the development of figural representation in a two-dimensional format. Stokstad plate 5-5 Geometric krater from the Dipylon cemetery, Athens, Greece, ca. 740 BCE. Approx. 3’ 4½“ high. [mixing bowl for wine and water] • • Geometric art Again the figures on the body of the krater are almost schematic in shape. The important factor in this depiction is the narrative value this vase contains. • Geometric art The funeral of the individual is shown and the mourners are demonstrating their grief by the gestures of raised arms. • • Geometric art Unlike the Egyptians, this is a straightforward depiction of a funeral; no mythic creatures are present. The difference is the representation of a funeral and the absence of gods escorting the deceased along the journey. • • Geometric art Another feature of vase painting is the use of the entire surface of the object as a platform for depiction This can be seen in an oinochoe (wine pitcher) which details the “Shipwreck of Odysseus” “Shipwreck of Odysseus” Late Geometric Oinochoe (wine jug), c. 725 BCE. Neck has scene of shipwreck (Odysseus?). •The neck of the pitcher shows the shipwreck, the crew helter skelter in space •The ship is shown as a series of oar ports •Odysseus, the largest figure, is behind the ship as if the last to leave the sinking vessel • • • • Geometric art The body of the pitcher has a series animals used as decorative motifs that cover the entire body of the pitcher. The vase painter involved the whole surface of the vessel and used figurative as well abstract bands to cover the surface. This is a departure from previous and contemporaneous traditions. The human figure has the place of importance in both of the vessels. Orientalizing Period, continued: • The Orientalizing style (700-600 BCE) was experimental and transitional compared with the Geometric style. • "Orientalizing Style" of Greek painted vases is marked by the imagery of the Near East, including zoomorphic imaginary animals and other designs traditionally identified as originating "east" of Greece. • Orientalizing was inconsistent: partly solid silhouettes, partly in outline, combinations. Orientalizing Period, continued: •Sphinxes and other Mesopotamian or Egyptian designs seen here indicate an "Orientalizing style.“ Orientalizing Period, continued: The Blinding of Polyphemus and Gorgons, on an Orientalizing (proto-Attic) vase, “Eleusis Amphora”, c.675-650BCE, Ht. 56” [an amphora was a storage jar] Orientalizing Period, continued: • The Orientalizing style reflects powerful influences form Egypt and the Near East, stimulated by increasing trade with these regions • The change is very clear in the Eleusis Amphora, if you compare it with the Dipylon Krater from 100 years earlier Orientalizing Period, continued: Orientalizing Period, continued: •Geometric ornament has not disappeared from this vase altogether, but it is confined to the peripheral zones: the foot, the handles, and the lip Orientalizing Period, continued: •Geometric ornament has not disappeared from this vase altogether, but it is confined to the peripheral zones: the foot, the handles, and the lip •New curvilinear motifs—such as spirals, interlacing bands, palmettes, and rosettes—are conspicuous everywhere. Orientalizing Period, continued: • On the shoulder we see a frieze of fighting animals, derived from the repertory of Near Eastern art. • The major areas, however, are given over to narrative, which has become the dominant element Orientalizing Period, continued: • On the shoulder we see a frieze of fighting animals, derived from the repertory of Near Eastern art. • The major areas, however, are given over to narrative, which has become the dominant element • This is the blinding of the giant one-eyed cyclops Polyphemus, by Odysseus and his companions, whom Polyphemus had imprisoned Orientalizing Period, continued: • On the shoulder we see a frieze of fighting animals, derived from the repertory of Near Eastern art. • The major areas, however, are given over to narrative, which has become the dominant element • This is the blinding of the giant one-eyed cyclops Polyphemus, by Odysseus and his companions, whom Polyphemus had imprisoned • Center register: Gorgons chase Perseus who has just decapitated Medusa Orientalizing Period, continued: • On the shoulder we see a frieze of fighting animals, derived from the repertory of Near Eastern art. • The major areas, however, are given over to narrative, which has become the dominant element • This is the blinding of the giant one-eyed cyclops Polyphemus, by Odysseus and his companions, whom Polyphemus had imprisoned • It is memorably direct and dramatically forceful on this vase. • Their movements have an expressive vigor that makes them seem thoroughly alive. Orientalizing Period, continued: • This olpe (an earthenware vase or pitcher without a spout) is similar to plate 5-4 in Gardner Stokstad plate 5-8 Pitcher (olpe) from Corinth, Greece, ca. 600 BCE. Approx. 1’ high. Ceramic with black-figure decoration Orientalizing Period, continued: • This olpe (an earthenware vase or pitcher without a spout) is similar to plate 5-4 in Gardner • Compare with the Ishtar Gate from earlier Mesopotamian Art and notice the Mesopotamian Art influences: Neo-Babylonian, 6th century BCE Greek, 7th century BCE Archaic Period: 600-480 BCE • The Archaic style emerged around 600 BCE and was dominant until 480 BCE (the time of the Greek victories over Persia). • Big difference was a new sense of artistic discipline of the latter, compared with the inconsistencies of the Orientalizing Style • Three categories of artwork in the Archaic Period: 1. sculpture 2. architecture 3. vase painting • Many people view this period as the most vital phase in Greek art, because of its vitality and freshness. Archaic Period: 600-480 BCE Archaic Sculpture: • We know that Greece imported ivory carvings and metalwork that was Phoenician or Syrian, also Egyptian. • But how do we explain the rise of monumental sculpture around 650 BCE? • Had to have gone to Egypt! • There were small colonies of Greeks in Egypt then • Who knows for sure; but oldest surviving Greek stone sculpture and architecture show that Egyptian tradition had already been assimilated and Hellenized. Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore: • large figures of standing male nudes and slightly smaller statues of clothed maidens • began to appear as dedications in religious sanctuaries and as grave markers • form of kouros: Stokstad plate 5-17 Kouros, ca. 600 BCE. Marble, approx. 6’½ “ high Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore: • large figures of standing male nudes and slightly smaller statues of clothed maidens • began to appear as dedications in religious sanctuaries and as grave markers • form of kouros: --standing with one leg forward Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore: • large figures of standing male nudes and slightly smaller statues of clothed maidens • began to appear as dedications in religious sanctuaries and as grave markers • form of kouros: --standing with one leg forward --arms held down to the side Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore: • large figures of standing male nudes and slightly smaller statues of clothed maidens • began to appear as dedications in religious sanctuaries and as grave markers • form of kouros: --standing with one leg forward --arms held down to the side --firsts clenched Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore: • large figures of standing male nudes and slightly smaller statues of clothed maidens • began to appear as dedications in religious sanctuaries and as grave markers • form of kouros: --standing with one leg forward --arms held down to the side --firsts clenched --looking rigidly ahead Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore: • large figures of standing male nudes and slightly smaller statues of clothed maidens • began to appear as dedications in religious sanctuaries and as grave markers • form of kouros: --standing with one leg forward --arms held down to the side --firsts clenched --looking rigidly ahead • probably inspired by Egyptian Sculpture: stances and proportions very similar Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore, continued: • notice in the Egyptian statue, spaces between arms and sides are filled by stone block and figure adheres to stone slab behind him—conveys sense of permanence • however, Egypt one seems more lifelike Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore, continued: • at this point, Greek sculptor is more interested in pattern than appearance: --face of kouros is play of contrasting curves that can be traced in eyebrow, too-large eyes, lips, wig --regular series of rolled forms, textured to contrast with smoothness of skin --Muscles represented by triangular shapes, more decorative than anatomical Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore, continued: • but kouros is separated form the block—fully in the round and more capable of movement Archaic Sculpture, continued Kouros and Kore, continued: • the kouros tight silhouette is less fleshy, more energetic and alert. • seems lively and eager to move, only incapable of doing so because muscles are decorative, not functional, and body is trapped in rigid stance Kroisos: Archaic Sculpture, continued Stokstad plate 5-18 Kroisos, from Anavysos, Greece, ca. 530 BCE. Marble, approx. 6’ 4” high. Kroisos: Archaic Sculpture, continued • identified on base as funerary statue of Kroisos, who had died a hero’s death in the front of line of battle Kroisos: Archaic Sculpture, continued • identified on base as funerary statue of Kroisos, who had died a hero’s death in the front of line of battle • originally painted (can still see traces of color) Kroisos: Archaic Sculpture, continued • identified on base as funerary statue of Kroisos, who had died a hero’s death in the front o line of battle • originally painted (can still see traces of color) • now swelling curves, greater awareness of massive volume, also new elasticity, more anatomically correct Kroisos: Archaic Sculpture, continued • identified on base as funerary statue of Kroisos, who had died a hero’s death in the front o line of battle • originally painted (can still see traces of color) • now swelling curves, greater awareness of massive volume, also new elasticity, more anatomically correct • like the transition from black-figured to red-figured pottery , which we’ll see later Calf-bearer: Archaic Sculpture, continued Stokstad plate 5-22 Calf Bearer (Moschophorus), dedicated by Rhonbos on the Acropolis, Athens, Greece, ca. 560 BCE. Marble, restored height approx. 5’ 5”. Calf-bearer: Archaic Sculpture, continued • votive figure of donor with the calf he is offering to Athena • thin cloak fits like second skin Calf-bearer: Archaic Sculpture, continued • votive figure of donor with the calf he is offering to Athena • thin cloak fits like second skin • face more realistic • lips draw up in a smile (“Archaic smile”)— same radiant expression occurs throughout 6th c. BCE Greek sculpture, even on Kroisos Calf-bearer: Archaic Sculpture, continued • lips draw up in a smile (“Archaic smile”)— same radiant expression occurs throughout 6th c. BCE Greek sculpture, even on Kroisos • The significance of the convention is not known, although it is often assumed that for the Greeks this kind of smile reflected a state of ideal health and well-being. It has also been suggested that it is simply the result of a technical difficulty in fitting the curved shape of the mouth to the somewhat blocklike head typical of Archaic sculpture. Rampin Head: Archaic Sculpture, continued Rampin Head from the Athenian Acropolis, Archaic Style, Greek, c.550 BCE Rampin Head: Archaic Sculpture, continued • Archaic smile more famous here Rampin Head: Archaic Sculpture, continued • Archaic smile more famous here • probably belonged to body of horseman Rampin Head: Archaic Sculpture, continued • Archaic smile more famous here • probably belonged to body of horseman • eyes are also smiling • to give it expression Archaic Sculpture, continued Kores: • female: kore [Gardner plate 5-7] Lady of Auxerre, statue of a goddess or kore, ca. 650-625 BCE. Limestone, approx. 2’ 1½“ high. Archaic Sculpture, continued Kores: • female: kore • kore type more variable –had to deal with how to relate figure and drapery • also reflected changing habits or local differences in dress. Archaic Sculpture, continued Kore in Peplos: Stokstad plate 5-20 Peplos Kore, from the Acropolis, Athens, Greece, ca. 530 BCE, Marble, approx. 4’ high. Archaic Sculpture, continued Kore in Peplos: • more of a linear descendant of first kore, though carved a full century later Archaic Sculpture, continued Kore in Peplos: • more of a linear descendant of first kore, though carved a full century later • blocklike rather than columnar, with strongly accented waist • new organic treatment of hair • full, round face with softer more natural smile • kind of like Kroisos Hera of Samos: Archaic Sculpture, continued Kore Figure Dedicated by Cheramyes to Hera, from the Sanctuary of Hera, Samos, circa 570560 BCE. Marble, 6 ft. 3 ½ in Hera of Samos: Archaic Sculpture, continued • found in temple of Hera on Island of Samos • May have been image of goddess because of great size and extraordinary dignity (she’s more than 6 feet tall, and that’s without a head!) • like a column come to life • smooth, continuous flow of lines uniting limbs and body • blossoms forth into swelling softness of a living body • several separate layers of garments Hera of Samos: • drapery is architectonic* up to knee regions, turns into second skin as in Calf-bearer *having qualities, like design and structure, that are characteristic of architecture Archaic Period: 600-480 BCE Archaic Architectural Sculpture: • Egyptian relief was shallow carvings that didn’t disturb the continuity of the wall surface; no weight or volume of their own interchangeable with Egyptian wall paintings Archaic Period: 600-480 BCE Archaic Architecture Sculpture: • But the Mycenaeans, possibly influenced by the Mesopotamians, brought in something new: --The Mycenaean lion gate sculpture is carved on a thin, light slab, not like the heavy, Cyclopean blocks around it Archaic Period: 600-480 BCE Archaic Architecture Sculpture: --they filled the hole-- Hittite lions gate Archaic Period: 600-480 BCE Archaic Architecture Sculpture: --they filled the hole--with a light weight triangular relief panel •this was something new--a sculpture that was integrated with the structure yet also a separate entity, rather than a modified wall surface or block Archaic Architectural Sculpture • The earliest pediment—Archaic Temple of Artemis, erected soon after 600 BCE on the island of Corfu Stokstad plate 5-11 Greece Island of Corfu Archaic Architectural Sculpture • The earliest pediment—Archaic Temple of Artemis, erected soon after 600 BCE on the island of Corfu • a pediment is the triangle between the horizontal ceiling and the sloping sides of the roof. To protect the wooden rafters behind it from moisture; later to take some weight off the door frame pediment Archaic Architectural Sculpture • The earliest pediment—Archaic Temple of Artemis, erected soon after 600 BCE on the island of Corfu • a pediment is the triangle between the horizontal ceiling and the sloping sides of the roof. To protect the wooden rafters behind it from moisture; later to take some weight off the door frame • related to Mycenaean Lion’s gate because here, sculpture is also confined to a zone that is framed by structural members but is itself structurally empty Stokstad plate 5-12 West pediment from the Temple of Artemis, Corfu, Greece, ca. 600-580 BCE. Limestone, greatest height approx. 9’ 4” . Archaic Architectural Sculpture • The pediment here is in high relief, but the bodies are strongly undercut so as to detach them from the background • purpose—the Greek sculptor wanted to assert the independence of his figures from their architectural setting Archaic Architectural Sculpture • The pediment here is in high relief, but the bodies are strongly undercut so as to detach them from the background • purpose—the Greek sculptor wanted to assert the independence of his figures from their architectural setting • The head of the central figure actually overlaps the frame Archaic Architectural Sculpture • central figure is a Gorgon: Archaic Architectural Sculpture • central figure is a Gorgon: --any of the three hideous sisters in Greek legend --including Medusa whose face turned beholders to stone • to serve as guardian, along with 2 huge lions/panthers Archaic Architectural Sculpture • central figure is a Gorgon: --any of the three hideous sisters in Gk. legend --including Medusa whose face turned beholders to stone • to serve as guardian, along with 2 huge lions • to ward off evil from the temple and the sacred image of the goddess within • an extraordinarily monumental and frightening hex sign— smile is hideous grin Archaic Architectural Sculpture • represented running or flying in a pinwheel stance that conveys movement without locomotion to emphasize how alive and real she is Archaic Architectural Sculpture • represented running or flying in a pinwheel stance that conveys movement without locomotion to emphasize how alive and real she is Archaic Architectural Sculpture • represented running or flying in a pinwheel stance that conveys movement without locomotion to emphasize how alive and real she is • also, number of smaller figures in spaces left between or behind huge main group (some sort of narrative) Archaic Architectural Sculpture • the design of the whole shows two conflicting purposes in uneasy balance: 1) the heraldic arrangement Archaic Architectural Sculpture • the design of the whole shows two conflicting purposes in uneasy balance: 1) the heraldic arrangement 2) juxtaposed with narrative arrangement. Archaic Architectural Sculpture Besides the pediment, the Greeks put architectural sculptures of free-standing figures (often of terra-cotta): 1. above the ends and center of pediment to break the severity of its outline Archaic Architectural Sculpture Besides the pediment, the Greeks put architectural sculptures of free-standing figures (often of terra-cotta): 1. above the ends and center of pediment to break the severity of its outline 2. in the zone immediately below the pediment Archaic Architectural Sculpture Besides the pediment, the Greeks put architectural sculptures of free-standing figures (often of terra-cotta): 1. above the ends and center of pediment to break the severity of its outline 2. in the zone immediately below the pediment 3. in metopes Archaic Architectural Sculpture Besides the pediment, the Greeks put architectural sculptures of free-standing figures (often of terra-cotta): 1. above the ends and center of pediment to break the severity of its outline 2. in the zone immediately below the pediment 3. in metopes 4. into columns by elaborating the columns into female statues (reminiscent of the columnar Hera Kore). Greek friezes: they evolved into a “frieze”-a continuous band of painted or sculpted decoration Archaic Architectural Sculpture Doric friezes: • a Doric frieze consists of alternating triglyphs* and metopes, ,the latter often sculpted Dipteral colonnade: the term used to describe the architectural feature of double colonnades around Greek temples. *The space between triglyphs in a Doric frieze. *An ornament in a Doric frieze, consisting of a projecting block having on its face three protruding vertical bars and two half grooves on either vertical end. Archaic Architectural Sculpture • an Ionic frieze is usually decorated with continuous relief sculpture Archaic Architectural Sculpture Stokstad plate 5-13. Reconstruction of the façade of the Treasury of the Siphnians in the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. c. 530 BCE • Temple for storing votive gifts Archaic Architectural Sculpture Reconstruction of the façade of the Treasury of the Siphnians in the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. • On the north frieze, Battle of Gods and Giants • Erected by the Ionians, just before 525 BCE Stokstad plate 5-14 Battle between the Gods and the Giants (Gigantomachy), from the north frieze of the Treasury of the Siphnians, Delphi, c.530-525 BCE, Marble, ht 26” Archaic Architectural Sculpture Reconstruction of the façade of the Treasury of the Siphnians in the Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi. • Here we see part of battle of the Greek gods (without armor) against the giants (with armor) Archaic Architectural Sculpture • 2 lions pull chariot of Cybele and are tearing apart an anguished giant Archaic Architectural Sculpture • 2 lions pull chariot of Cybele and are tearing apart an anguished giant Archaic Architectural Sculpture • 2 lions pull chariot of Cybele and are tearing apart an anguished giant Archaic Architectural Sculpture • on left, 2 lions pull chariot of Cybele and are tearing apart an anguished giant • In front of them, Apollo and Artemis advance together, shooting arrows Archaic Architectural Sculpture • on left, 2 lions pull chariot of Cybele and are tearing apart an anguished giant • In front of them, Apollo and Artemis advance together, shooting arrows • A dead giant, despoiled of his armor, lies at their feet while 3 others enter form the right Archaic Architectural Sculpture • on left, 2 lions pull chariot of Cybele and are tearing apart an anguished giant • In front of them, Apollo and Artemis advance together, shooting arrows • A dead giant, despoiled of his armor, lies at their feet while 3 others enter from the right Archaic Architectural Sculpture High relief with deep undercutting, like Corfu pediment, but this one takes full advantage of the spatial possibilities offered by this technique: • Projecting ledge at bottom of frieze is used as a stage to place figures in depth. • In nearest layer, arms and legs completely in round Archaic Architectural Sculpture High relief with deep undercutting, like Corfu pediment, but this one takes full advantage of the spatial possibilities offered by this technique: • Projecting ledge at bottom of frieze is used as a stage to place figures in depth. • In nearest layer, arms and legs completely in round • in second and third layers, forms more shallow, but never merge with background Archaic Architectural Sculpture High relief with deep undercutting, like Corfu pediment, but this one takes full advantage of the spatial possibilities offered by this technique: • Projecting ledge at bottom of frieze is used as a stage to place figures in depth. • In nearest layer, arms and legs completely in round • in second and third layers, forms more shallow, but never merge with background • Result: limited and condensed by convincing space that permits a dramatic relationship between the figures that we’ve never seen before in narrative reliefs New dimension in physical and expressive sense! Transition to the Classical Period By the time we get to the Temple of Aphaia (40 years later), • relief has been abandoned Transition to the Classical Period By the time we get to the Temple of Aphaia (40 years later), • relief has been abandoned • separate statues are placed side by side in complex dramatic sequences designed to fit the triangular frame. Transition to the Classical Period • West pediment: ca. 500-490 BCE; East pediment: 490 BCE Stokstad plate 5-15 (Bottom one) Transition to the Classical Period • West pediment: ca. 500-490 BCE; East pediment: 490 BCE • Height but not scale varies with sloping sides of the triangle Transition to the Classical Period • West pediment: ca. 500-490 BCE; East pediment: 490 BCE • Height but not scale varies with sloping sides of the triangle • center accented by standing symmetrically diminishing fashion Transition to the Classical Period • West pediment: ca. 500-490 BCE; East pediment: 490 BCE • Height but not scale varies with sloping sides of the triangle • center accented by standing symmetrically diminishing fashion • balance and order from corresponding poses of the fighters on the two halves. Transition to the Classical Period • West pediment: ca. 500-490 BCE; East pediment: 490 BCE • Height but not scale varies with sloping sides of the triangle • center accented by standing symmetrically diminishing fashion • balance and order from corresponding poses of the fighters on the two halves. • forces us to see the statues as elements in an ornamental pattern and robs them of individuality Transition to the Classical Period • more individual one by one, e.g. Dying warrior Stokstad plate 5-16 Dying warrior, from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia, ca. 490-480 BCE. Marble, approx. 6’ 1” long. Transition to the Classical Period • more individual one by one, e.g. Dying warrior • on left, fallen warrior, on right, Kneeling Herakles who once held bronze now Transition to the Classical Period • more individual one by one, e.g. Dying warrior • on left, fallen warrior, Kneeling Herakles who once held bronze now • Both lean, muscular, bodies very functional and organize, very firm shapes Transition to the Classical Period • more individual one by one, e.g. Dying warrior • on left, fallen warrior, Kneeling Herakles who once held bronze now • Both lean, muscular, bodies very functional and organize, very firm shapes • really move us: nobility of spirit: they are suffering or carrying out what fate has decreed with tremendous dignity and resolve Archaic Period: 600-480 BCE Archaic Vase Painting: • The unique quality of Archaic vase painting is the quality of the painting—they are truly works of art • Archaic vases were smaller than their predecessors because they no longer used pottery for grave monuments (they switched to stone for that) • Black-figured vase painting technique • Then red-figured vase painting technique Archaic Vase Painting, continued: • After the middle of the 6th c. BCE, the finest vases bore the signatures of the artists who made them • shows that individual potters and painters took pride, and also that they could become famous, e.g. : --Exekias (black-figured) Archaic Vase Painting, continued: • After the middle of the 6th c. BCE, the finest vases bore the signatures of the artists who made them • shows that individual potters and painters took pride, and also that they could become famous, e.g. : --Exekias (black-figured) --Psiax (black-figured) Archaic Vase Painting, continued: • After the middle of the 6th c. BCE, the finest vases bore the signatures of the artists who made them • shows that individual potters and painters took pride, and also that they could become famous, e.g. : --Exekias (black-figured) --Psiax (black-figured) --Douris (red-figured) • • • • • • Archaic Vase Painting, continued: After the middle of the 6th c. BCE, the finest vases bore the signatures of the artists who made them shows that individual potters and painters took pride, and also that they could become famous, e.g. : --Exekias (black-figured) --Psiax (black-figured) --Douris (red-figured) Other kinds of Archaic Greek painting were murals and panels. Like the vases, all Archaic Greek paintings were essentially drawing filled in with solid, flat color According to literary sources, Greek wall painting came into its own around 475-450 BCE After the Persian wars, there was a gradual discovery of modeling and spatial depth, and the importance of vase painting declined Archaic Vase Painting, continued: kylix Archaic Vase Painting, continued: Black-figured Style First developed was the “black-figured style”: • entire design is silhouetted in black against the reddish clay • internal details incised with a needle • sometimes white or purple added on top of the black Virtue of this style was a decorative, two-dimensional effect Black-figured Style, continued: Nessos Painter, Nessos Amphora, Attic black figure Amphora, last quarter of the seventh century B.C.E. • early black-figure attic amphora • the neck of the vase bears the representation of Herakles killing the Centaur Nessos. • on the belly, two fearsome Gorgons are depicted running to the right and behind them the mythical Medusa, decapitated by Perseus Black-figured Style, continued: Nessos Painter, Nessos Amphora, Attic black figure Amphora, last quarter of the seventh century B.C. • early black-figure attic amphora • the neck of the vase bears the representation of Herakles killing the Centaur Nessos. • on the belly, two fearsome Gorgons are depicted running to the right and behind them the mythical Medusa, decapitated by Perseus • It was found in Athens and is most characteristic work of the Nessos Painter. Dated to ca. 620 BCE. Black-figured Style, continued: Exekias, Dionysus in a Boat, interior of Attic black-figured kylix, c.540 BCE, ceramic, diameter 12”. Black-figured Style, continued: Exekias, Dionysus in a Boat, interior of Attic black-figured kylix, c.540 BCE, ceramic, diameter 12”. • slender, sharp-edged forms have a lacelike delicacy, yet also resilience and strength • the composition adapts itself to the circular surface without becoming mere ornament • sail was once entirely white • boat moves with the same ease as the dolphins, whose lithe forms are counterbalanced by the heavy clusters of grapes According to a Homeric hymn: --Dionysus the god of wine was once abducted by pirates --he caused vines to grow all over the ship --the frightened captors jumped overboard and were turned into dolphins seven dolphins and seven bunches of grapes for good luck spare elegance is reminiscent of Geometric style Black-figured Style, continued: [Gardner plate 5-19] Exekias, Achilles and Ajax playing a dice game (detail form an Athenian black-figure amphora), ca. 540-530 BCE. Whole vessel approx. 2’ high • • • • Black-figured Style, continued: Exekias master of black-figure his vases were widely exported and copied Exekias signed this one as both painter and potter one single large framed panel is peopled by figures of monumental stature • • • • • • Black-figured Style, continued: Exekias master of black-figure his vases were widely exported and copied Exekias signed this one as both painter and potter one single large framed panel is peopled by figures of monumental stature at left, Achilles, fully armed plays dice game with his friend Ajax. • • • • • • • Black-figured Style, continued: Exekias master of black-figure his vases were widely exported and copied Exekias signed this one as both painter and potter one single large framed panel is peopled by figures of monumental stature at left, Achilles, fully armed plays dice game with his friend Ajax. classic case of “calm before the storm” • • • • • • • • Black-figured Style, continued: Exekias master of black-figure his vases were widely exported and copied Exekias signed this one as both painter and potter one single large framed panel is peopled by figures of monumental stature at left, Achilles, fully armed plays dice game with his friend Ajax. classic case of “calm before the storm” Exekias has no equal as a black-figure painter-extraordinarily intricate engraving of the patterns of the heroes’ cloaks (highlighted with delicate touches of white) and in the brilliant composition Black-figured Style, continued: • the arch formed by the backs of the two warriors echoes the shape of the rounded shoulders of the amphora • vessel’s shape is echoed again in the void between the heads and spears of Achilles and Ajax Black-figured Style, continued: • the arch formed by the backs of the two warriors echoes the shape of the rounded shoulders of the amphora • vessel’s shape is echoed again in the void between the heads and spears of Achilles and Ajax • Exekias used the spears to lead the viewer’s eyes toward the thrown dice, where the heroes’ eyes are fixed • the eyes don’t really look down as but stare out from the profile heads in the old manner Black-figured Style, continued: Stokstad plate 5-24 "François Vase", volute krater signed by Kleitias as painter and Ergotimos as potter, 570 BCE. Approx. 2’2” high. Black-figured Style, continued: "François Vase”: • Athenians learned the black-figure technique from the Corinthians, then became known for and exported blackfigured vases • It’s actually signed by both the painter and potter 9twice!) • More than 200 figures in 6 registers • Only one band is Orientalizing repertoire of animals and sphinxes • The rest constitutes a selective encyclopedia of Greek mythology, especially Peleus and his son Achilles and Theseus Black-figured Style, continued: Stokstad plate 5-24 "François Vase“: detail of Lapith and centaur, • Here, Lapiths (a northern Greek tribe) and centaurs battle (centauromachy) after a wedding celebration where the centaurs (who were invited) got drunk and tried to abduct the Lapith maidens and young boys • Theseus was one of the centaurs’ Greek adversaries • His heroes conforms to the age-old composite type (profile heads with frontal eyes frontal torsos, and profile legs and arms Black-figured Style, continued: "François Vase“: detail of Lapith and centaur, Gardner plate 5-18 • The centaurs are much more believable • Notice his centaurs are top/bottom rather than front/back Black-figured Style, continued: Psiax, Herakles Strangling the Nemean Lion, on a black-figured amphora, c.525 BCE, ht 19½“ Black-figured Style, continued: Psiax, Herakles Strangling the Nemean Lion, on a black-figured amphora, c.525 BCE, ht 19½” • Psiax’ work was the direct artistic outgrowth of the Orientalizing style of the Blinding of Polyphemus on the Eleusis Amphora Black-figured Style, continued: Psiax, Herakles Strangling the Nemean Lion, on a black-figured amphora, c.525 BCE, ht 19½” • Psiax’ work was the direct artistic outgrowth of the Orientalizing style of the Blinding of Polyphemus on the Eleusis Amphora • Like the sound box of the harp from Ur, it shows a hero facing the unknown forces of life embodied by terrifying mythical creatures Black-figured Style, continued: Psiax, Herakles Strangling the Nemean Lion, on a black-figured amphora, c.525 BCE, ht 19½” • Psiax’ work was the direct artistic outgrowth of the Orientalizing style of the Blinding of Polyphemus on the Eleusis Amphora • Like the sound box of the harp from Ur, it shows a hero facing the unknown forces of life embodied by terrifying mythical creatures • Lion also underscored hero’s might and courage against demonic forces Black-figured Style, continued: Psiax, Herakles Strangling the Nemean Lion, on a black-figured amphora, c.525 BCE, ht 19½” • Psiax’ work was the direct artistic outgrowth of the Orientalizing style of the Blinding of Polyphemus on the Eleusis Amphora • Like the sound box of the harp from Ur, it shows a hero facing the unknown forces of life embodied by terrifying mythical creatures • Lion also underscored hero’s might and courage against demonic forces • Scene is grim and violent • The 2 heavy bodies are truly locked in combat, so they almost grow together into a single, compact unit Black-figured Style, continued: Psiax, Herakles Strangling the Nemean Lion, on a black-figured amphora, c.525 BCE, ht 19½” • incised lines and subsidiary colors added with utmost economy to avoid breaking up the massive expanse of black • figures show wealth of knowledge of anatomical structure and skillful use of foreshortening—gives amazing illusion of existing in the round • note the abdomen and shoulders of Herakles Black-figured Style, continued: Psiax, Herakles Strangling the Nemean Lion, on a black-figured amphora, c.525 BCE, ht 19½” • incised lines and subsidiary colors added with utmost economy to avoid breaking up the massive expanse of black • figures show wealth of knowledge of anatomical structure and skillful use of foreshortening—gives amazing illusion of existing in the round • note the abdomen and shoulders of Herakles • Only in the eye of Herakles do we still find the traditional combination of front and profile view Black-figured Style, continued: “Bilingual Painting”: • created by the Andokides Painter (the anonymous painter who decorated the vases signed by the potter Andokides) • Same composition on both sides: --one in black-figured technique Black-figured Style, continued: “Bilingual Painting”: • created by the Andokides Painter (the anonymous painter who decorated the vases signed by the potter Andokides) • Same composition on both sides: --one in black-figured technique --one in red-figured technique Black-figured Style, continued: “Bilingual Painting”: • created by the Andokides Painter (the anonymous painter who decorated the vases signed by the potter Andokides) • Same composition on both sides: --one in black-figured technique --one in red-figured technique • bilingual style didn’t last long—people moved to redfigured Archaic Vase Painting, continued: Red-figured Style • next developed was the “red-figured style” • the figures are left red and the background is filled in with black • details on figures painted in with a brush • this style gradually replaced the black-figured style toward 500 BCE • “red-figure” works look more 3-d to us—close to the way we see light than black-figured, which looks more like a photographic negative Red-figured Style, continued: • Attic red figure kylix. A warrior about ready to leave home. 5th century BCE, British Museum. • [The “white” part is red in real life; this is a black and white photo—sorry!] Red-figured Style, continued: • Attic red figure kylix. A warrior about ready to leave home. 5th century BC, British Museum. • Details are now freely drawn in with the brush, rather than laboriously incised • now we have more details of costume, facial expression • figure almost seems to burst from the circular form Foundry Painter, Pankratiasts, boxers and other athletes, redfigured cup, Greek, about 500-475 BCE Made in Athens, Greece; found at Vulci (now in Lazio, Italy) Stokstad plate 5-29 Foundry Painter, Pankratiasts, boxers and other athletes, redfigured cup, Greek, about 500-475 BC Made in Athens, Greece; found at Vulci (now in Lazio, Italy) • Athletic achievement was highly valued in ancient Greek society Foundry Painter, Pankratiasts, boxers and other athletes, redfigured cup, Greek, about 500-475 BC Made in Athens, Greece; found at Vulci (now in Lazio, Italy) • Athletic achievement was highly valued in ancient Greek society •Physical fitness was important, as all adult males had to be prepared to serve in the army if required. •Sports of all types were a major part of Greek education, and athletic competitions took place at many of the major festivals. •The most famous games were held at Olympia, and the pankration, illustrated here, was an Olympic sport •It was a type of all-in wrestling in which practically anything, including kicking or trying to strangle your opponent, was allowed Foundry Painter, Pankratiasts •The only activities that were banned were biting and trying to gouge out your opponent's eyes. •The right-hand pankratiast in this group appears to be committing both kinds of foul, and the trainer behind him is about to bring his stick down hard upon the his back. •To the left of the pankratiasts are a pair of boxers •on the other side of the cup are a youth preparing to race in armor, more boxers and a trainer, and a youth stretching a thong of the type boxers wrapped around their hands and wrists. Red-figured Style, continued: Euphronios (painter) and Euxitheos (potter), Death of Sarpedon, c.515 BCE, Red-figure decoration on a calyx krater. Ceramic, nt. 18” Stokstad plate 5-28 • Euphronios—well known red-figure artist who was praised especially for his study of human anatomy According to Homer's Iliad: • Sarpedon--a son of Zeus and a mortal woman • was killed by the Greek warrior Patroclus while fighting for the Trojans. Red-figured Style, continued: Euphronios shows: • the winged figures of Hypnos (Sleep) and Thanatos (Death) carrying the dead warrior from the battlefield Red-figured Style, continued: • Watching over the scene is Hermes, the messenger of the gods— --identified by his winged hat and caduceus, a staff with coiled snakes (caduceus--now used as a medical symbol) --Hermes is there in another important role, as the guide who leads the dead to the netherworld. Red-figured Style, continued: Euthymides, Three Revelers (Attic red-figure amphora), ca. 510 BCE, approx. 2’ high Gardner plate 5-22 • Euthymides was a contemporary and competitor of Euphronios • subject appropriate for a wine storage jar—three tipsy revelers • theme was little more than an excuse for the artist to experiment with the representation of unusual positions of the human form Red-figured Style, continued: [Gardner plate 5-22] Euthymides, Three Revelers (Attic red-figure amphora), ca. 510 BCE, approx. 2’ high • Euthymides was a contemporary and competitor of Euphronios • subject appropriate for a wine storage jar—three tipsy revelers • theme was little more than an excuse for the artist to experiment with the representation of unusual positions of the human form • no coincidence that the bodies do not overlap, because each is an independent figure study Red-figured Style, continued: Euthymides, Three Revelers • Euthymides rejected the conventional frontal and profile composite views Red-figured Style, continued: Euthymides, Three Revelers • Euthymides rejected the conventional frontal and profile composite views • instead he painted torsos that are not 2-d surface patterns but are foreshortened (i.e. drawn in a ¾ view) Red-figured Style, continued: Euthymides, Three Revelers • Euthymides rejected the conventional frontal and profile composite views • instead he painted torsos that are not 2-d surface patterns but are foreshortened (i.e. drawn in a ¾ view) • most remarkable is the central figure, shown from rear with a twisting spinal columnar and butt in ¾ view Red-figured Style, continued: Euthymides, Three Revelers • Euthymides rejected the conventional frontal and profile composite views • instead he painted torsos that are not 2-d surface patters but are foreshortened (i.e. drawn in a ¾ view) • most remarkable is the central figure, shown from rear with a twisting spinal columnar and butt in ¾ view • understandable pride: “Euthymides painted me as never Euphronios [could do]” Greek Architecture: • Three classical Greek Architectural orders: 1. Doric (most basic) 2. Ionic 3. Corinthian (variant of Ionic) • “Architectural order”: --term used only for Greek architecture and its descendants --elements are extraordinarily constant in number, kind, and relation to one another --so Doric temples all belong to same clearly recognizable family, like Kouros statues --they show an internal consistency, mutual adjustment of parts, that gives them a unique quality of wholeness and organic unity. Greek Architecture: • in general, Greek architecture could be summed up with the word “perfect”, whereas Egyptian architecture would be “forever” • the Greek orders were considered so beautiful for so long because: --the expression of force and counterforce were proportioned so exactly --that their opposition produced the effect of a perfect balancing of forces and harmonizing of sizes and shapes Greek Architecture: To study architecture, have to look at: • actual purposes of building 2. aesthetic impulse as motivating force Doric Order: • Doric order is: --the standard parts --and their sequence --constituting the exterior of any Doric temple • three main divisions: Gardner p. 113 Doric Order: • the whole structure was built of stone blocks fitted together without mortar, so needed extreme precision to achieve smooth joints • where necessary, fastened together with metal dowels or clamps. •columns usually composed of sections called “drums”. •Roof consisted of terra-cotta tiles supported by wooden rafters and wooden beams were used for the ceiling. Doric Order: Typical plan of a Greek temple: • nucleus is cella (room in which the image of the deity is placed: also called naos) and the porch (pronaos) with its two columns flanked by pilasters. Doric Order: Typical plan of a Greek temple: • nucleus is cella (room in which the image of the deity is placed: also called naos) and the porch (pronaos) with its two columns flanked by pilasters. Doric Order: Typical plan of a Greek temple: • nucleus is cella (room in which the image of the deity is placed: also called naos) and the porch (pronaos) with its two columns flanked by pilasters. Doric Order: Typical plan of a Greek temple: • nucleus is cella (room in which the image of the deity is placed: also called naos) and the porch (pronaos) with its two columns flanked by pilasters. Doric Order: Typical plan of a Greek temple: • nucleus is cella (room in which the image of the deity is placed: also called naos) and the porch (pronaos) with its two columns flanked by pilasters. • often has a second porch added behind the cella to make the design more symmetrical. Doric Order: Typical plan of a Greek temple: • nucleus is cella (room in which the image of the deity is placed: also called naos) and the porch (pronaos) with its two columns flanked by pilasters. • often has a second porch added behind the cella to make the design more symmetrical. • in larger temple, entire unit is surrounded by a colonnade and the structure is then known as a peripteral. ☻ Doric Order: Typical plan of a Greek temple: • nucleus is cella (room in which the image of the deity is placed: also called naos) and the porch (pronaos) with its two columns flanked by pilasters. • often has a second porch added behind the cella to make the design more symmetrical. • in larger temple, entire unit is surrounded by a colonnade and the structure is then known as peripteral. • very large Ionian Greek temples may even have had a double colonnade Doric Order: Typical plan of a Greek temple: • nucleus is cella (room in which the image of the deity is placed: also called naos) and the porch (pronaos) with its two columns flanked by pilasters. • often has a second porch added behind the cella to make the design more symmetrical. • in larger temple, entire unit is surrounded by a colonnade and the structure is then known as peripteral. • very large Ionian Greek temples may even have had a double colonnade • the earliest stone temple known to us shows that the essential features of the Doric order were already wellestablished soon after 600 BCE. Doric Order: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: Greek Architecture: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: Egyptian: a. shaft of Doric column tapers upward not downward; Doric Egyptian Greek Architecture: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: Egyptian: a. shaft of Doric column tapers upward not downward; b. peripteral temple could be interpreted as the common court of an Egyptian sanctuary but turned inside out; Greek peripteral Egyptian hypostyle hall Greek Architecture: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: Egyptian: a. shaft of Doric column tapers upward not downward; b. peripteral temple could be interpreted as the common court of an Egyptian sanctuary but turned inside out; c. stonecutting and masonry techniques from the Egyptians, along with architectural ornament and the knowledge of geometry needed to lay out temple and fit the parts together Greek Architecture: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: Mycenae: a. megaron led to cella and porch Greek Architecture: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: Mycenae: a. megaron led to cella and porch b. entire Mycenaean era had become part of Greek mythology (Homeric epics; walls of Mycenaean fortresses were believed to be he work of Cyclopes) Greek Architecture: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: Mycenae: a. megaron led to cella and porch b. entire Mycenaean era had become part of Greek mythology (Homeric epics; walls of Mycenaean fortresses were believed to be he work of Cyclopes) c. Lions gate relief led to sculptured pediments on Doric temples Greek Architecture: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: Mycenae: a. megaron led to cella and porch b. entire Mycenaean era had become part of Greek mythology (Homeric epics; walls of Mycenaean fortresses were believed to be he work of Cyclopes) c. Lions gate relief led to sculptured pediments on Doric temples d. Doric echinus and abacus closer to Minoan/Mycenaean capital than Egyptian Minoan capital Doric capital Greek Architecture: Egypt, Mycenae, and pre-Archaic Greek architecture in wood and mud brick were the three distinct sources of inspiration of early Greek builders in stone: PreArchaic Greek: a. Greek architecture in wood and mud brick b. didn’t survive because of their building materials Greek Architecture: What is the possible purpose for which certain architectural elements were derived? • triglyphs: could have been to mask the ends of the wooden beams Greek Architecture: What is the possible purpose for which certain architectural elements were derived? • triglyphs: could have been to mask the ends of the wooden beams 2. guttae: descendants of wooden pegs Greek Architecture: What is the possible purpose for which certain architectural elements were derived? • triglyphs: could have been to mask the ends of the wooden beams 2. guttae: descendants of wooden pegs 3. flutes on columns: Greek Architecture: What is the possible purpose for which certain architectural elements were derived? • triglyphs: could have been to mask the ends of the wooden beams 2. guttae: descendants of wooden pegs 3. flutes on columns: • could have been the adz (tool used to cut/shape wood) marks on a tree trunk? Greek Architecture: What is the possible purpose for which certain architectural elements were derived? • triglyphs: could have been to mask the ends of the wooden beams 2. guttae: descendants of wooden pegs 3. flutes on columns: • could have been the adz (tool used to cut/shape wood) marks on a tree trunk? • bundles of reeds? papyrus column at Luxor Greek Architecture: What is the possible purpose for which certain architectural elements were derived? • triglyphs: could have been to mask the ends of the wooden beams 2. guttae: descendants of wooden pegs 3. flutes on columns: • could have been the adz (tool used to cut/shape wood) marks on a tree trunk? • bundles of reeds? • may have been way to disguise horizontal joints between drums and stress continuity of the shaft as a vertical unit. A fluted shaft looks stronger, more energetic and resilient than a smooth one Greek Architecture: B. Archaic Architecture: • Best preserved 6th c. BCE Doric temple is the “Basilica” at Paestum in southern Italy, 550 BCE/Stokstad plate 5-9 Greek Architecture: B. Archaic Architecture: • (next to Temple of Poseidon/Hera II, built 100 years later, around 460 BCE) [Gardner plate 5-29] Archaic Architecture: B. “Basilica” at Paestum, Italy: • “Basilica” low and sprawling not only because much of the entablature is missing; while Temple looks tall and compact. Greek Architecture: B. Ionic Order: Greek Architecture: B. Ionic Order: • Ionic architrave generally had a continuous sculpted frieze instead of triglyphs and metopes. Greek Architecture: B. Ionic Order: • Ionic architrave generally had a continuous sculptured frieze instead of triglyphs and metopes. • Came into its height during the Classical period. Its most striking feature is the volute: a double scroll capital Greek Architecture: B. Ionic Order: • Ionic architrave generally had a continuous sutured frieze instead of triglyphs and metopes. • Came into its height during the Classical period. Its most striking feature is the volute: a double scroll capital • compared with Doric order, Ionic columns differed in body and spirit. Rests on ornately styled base. Capital shows large double scroll under the abacus. In general the Ionic columns look lighter and more graceful: not muscular. Evokes growing plantlike formalized palm tree. All the way back to papyrus columns. Greek Architecture: B. Ionic Order: • Ionic architrave generally had a continuous sutured frieze instead of triglyphs and metopes. • Came into its height during the Classical period. Its most striking feature is the volute: a double scroll capital • compared with Doric order, Ionic columns differed in body and spirit. Rests on ornately styled base. Capital shows large double scroll under the abacus. In general the Ionic columns look lighter and more graceful: not muscular. Evokes growing plantlike formalized palm tree. All the way back to papyrus columns. • Earliest Ionic buildings were small treasuries in pre-classical times. Greek Architecture: Corinthian Order: • A Corinthian capital is in the shape of an inverted bell covered with curly shoots and leaves of the acanthus plant. [Gardner plate 5-72] Polykleitos the Younger, Corinthian capital, from the tholos At Epidauros, Greece, ca. 350 BCE tholos -- in ancient Greek architecture, a circular building with a conical or vaulted roof and with or without a peristyle, or surrounding colonnade Stokstad plate 5-54 Tholos, Santuar of Athena Pronaia, Delphi, Greece, ca 400 BCE Greek Architecture: B. Corinthian Order: • A Corinthian capital is in the shape of an inverted bell covered with curly shoots and leaves of the acanthus plant. • the earliest known use of a Corinthian capital on an exterior was in 334 BCE, in a monument of Lysicrates in Athens: an elaborate support for a tripod won by Lysicrates in a contest. Mini-version of a tholos. • But the Romans used Corinthian capitals the most Severe Style (Early Classical Period: Severe Style • really just a difference in the sculpture • we don’t know of any portraiture in this period Severe Style: Severe Style Kritios boy was made just before 480 BCE and survived the Persian destruction of the Acropolis. It differs from the Archaic Kouros figures as follows: Gardner plate 5-33 Kritios Boy, from the Acropolis, Athens, Greece, ca. 480 BCE. Marble, approx. 2’ 10” high. Severe Style: Severe Style Kritios boy was made just before 480 BCE and survived the Persian destruction of the Acropolis. It differs from the Archaic Kouros figures as follows: • stands in the full sense of the word, as opposed to an arrested walk. • Earlier ones look military, as if soldiers standing at attention Kritios is clearly standing still. • Strict symmetry has given way to calculated nonsymmetry. • Knee of forward leg is lower than other, right hip thrust down and inward, left hip up and outward, axis of body not straight vertical line but faint reversed s-curve. • Shows us that weight of body rests mainly on left leg and right leg is a buttress to make sure the body keeps in balance. Severe Style: Kritios Boy • This is “contrapossto”. Italian word for counterpoise, set against. A method developed by the Greeks to represent freedom of movement in a figure. * The disposition of the human figure in which one part is turned in opposition to another part (usually hips and legs one way, shoulders and chest another), creating a counter-positioning of the body about its central axis. Sometimes called “weight shift” because the weight of the body tends to be thrown to one foot, creating tension on one side and relaxation on the other. • • • • Severe Style: Kritios Boy This is “contrapossto”. Italian word for counterpoise, set against. A method developed by the Greeks to represent freedom of movement in a figure. The parts of the body are placed asymmetrically in opposition to each other around a central axis, and careful attention is paid to the distribution of the weight. The leg that carries the main weight is commonly called the “engaged leg”. and the other the “free leg”. Very basic discovery see also Donatello’s David Gardner plate 5-33 Donatello, David, c. 1450 CE, Bronze, ht ~5’2” Stokstad plate 17-53 • • • • • Severe Style: this was an important discovery, because only by learning how to present the body at rest could the Greek sculptor gain the freedom to show it in motion, in a less mechanical and inflexible way than Archaic art. Here, we feel the emotion. Not only a new repose but an animation of the body structure that evokes the experience of our own body, because contrapossto brings the subtle curvatures—knee, swiveling, compensating curvature of the spine, adjusting tilt of the shoulders. Like Parthenon, the variations have nothing to do with statue’s ability to maintain itself erect but greatly enhance its lifelike impression. Even in repose, still seems capable of movement; in motion, of maintaining its stability. Severe Style: • Now the archaic smile, the “sign of life” is no longer needed. • Given way to serious, pensive expression characteristic of the early phase of Classical sculpture, also called the Severe style. • Describes the character of Greek sculpture between 480 and 450 B.C.E.. • • • • Severe Style: Riace warriors: made of bronze, ~450 BCE. We don’t know a lot about them. Second is a warrior, not an athlete. Faces very real, not idealization. More ethnic/. Maybe heroes? Rare to find extant Greek bronze statues at all, and these still have ivory and glass-paste eyes, bronze eyelashes, copper lips and nipples. Stokstad plate 5-35 Warrior on right, from the sea off Riace, Italy, Ca. 460-450 BCE. Bronze, approx. 6’ 6” high. Severe Style: • Charioteer: Unique. • Drapery reflects the behavior of real cloth. • Body and drapery transformed by new understanding of functional relationships, gravity, shape of body, belts or straps construct the flow of the cloth. Stokstad plate 5-34 Charioteer, from a group dedicated by Polyzalos of Gela In the Sanctuary of Apollo, Delphi, Greece, ca. 470 BCE. Bronze, approx. 5’ 11” high. More animated expression than Kritios Boy: color inlay of eyes and slightly parted lips. Charioteer Kritios Boy Severe Style: • Battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs, from west pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, c. 460 BCE marble, slightly over life-size. Stokstad plate 5-31 • You can tell the central figure is a god because the outstretched right arm and strong turn of the head show active intervention. He wills the victory but does not physically help to achieve it. • Tenseness, gathering of forces in powerful body that make outward calm doubly impressive. Severe Style: • It was harder to infuse the freedom of movement that we see in the pedimental sculpture at the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina, into free-standing statues, because it ran counter to age-old tradition that denied mobility to these figures. So the unfreezing had to be done is such a way to safeguard their all around balance and self-sufficiency. Needed contrapossto to tackle it. • The most important achievement of the Severe style was the large, free-standing statues in motion. Finest example— recovered from the sea near the coast of Greece—nude bronze, almost 7 feet tall. Probably Poseidon hurling trident (or Zeus, thunderbolt?). • “Stability in the midst of action becomes outright grandeur.” – Janson [Gardner plate 5-36] Zeus (or Poseidon?), From the sea off Cape Artemsion, Greece, ca. 460-450 BCE. Bronze, approx. 6’ 10” high.