Polymaths_Watson

advertisement

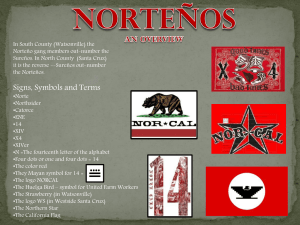

Pioneering Polymaths in Ecology, Biogeography, and Palaeoecology John Birks The Past is a Foreign Country – David Lowenthal 1985 Polymath from Greek polymathes – ‘having learned so much’ ‘a person whose expertise spans a significant number of different subject areas’ First used in 17 th century but related term polyhistor is an ancient term with similar meaning, as is phrase universal genius First applied to great scholars and thinkers of the Renaissance who excelled at multiple fields of the arts and sciences Leonardo da Vinci Galileo Galilei Francis Bacon Leon Battista Alberti Michelangelo Nicolaus Copernicus Michael Servetus “A man (sic) can do all things if he (sic) will” Concept built on basic tenet of Renaissance humanism – humans are empowered and limitless in their capacities for development. Led to notion that people should embrace all knowledge and develop their capacities as fully as possible. Renaissance ideal Renaissance period was a cultural movement in 14-17 th centuries. Began in Italy in late Middle Ages and spread later to the rest of Europe. A gentleman expected to speak several languages, write poetry, play a musical instrument, etc. ‘Renaissance ideal’ University education was pivotal to achieving polymath ability. Trained students in science, philosophy, and theology. No specialisation. The Renaissance ideal Baldassare Castiglione The Book of the Courtier discusses polymathic traits, ‘sprezzatura’ • • • • • • • • • detached, cool, nonchalant attitude speaks well, sings, recites poetry has proper hearing is athletic knows humanities and classics paints and draws not showy or boastful many, many other skills does or says things without effort Being an accomplished athlete is integral part of education and learning. Alberti was a Roman Catholic priest, architect, painter, poet, scientist, mathematician, inventor, and sculptor, as well as a skilled horseman and archer. Contrast with Robert Heinlein (1973) Time Enough for Love “A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, steer a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, and die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.” Other terms related to polymath: Renaissance man (or woman) Homo Universalis Uomo Universale – Universal Genius Generalist – ‘Jack of all trades’ Multi-tasker (cf. Jack of all trades, master of none) Often quoted that men cannot multi-task – do not agree! What has this to do with ecology, biogeography, and palaeoecology and the EECRG? Several connected ideas behind my interest in polymaths • Discussions about teaching and education, new courses, increasing or decreasing specialisations, etc. • Rare, endangered, and extinct species – is the polymath extinct? • Are we providing training and education for potential polymaths? • Increasing personal interest in history of my subjects of palaeoecology, biogeography, and ecology (symptom of old age!) • Has progress in these subjects been made by polymaths or specialists? Who are the pioneering polymaths in our subjects? Charles Darwin (1809-1882) Alfred Russel Wallace (1823-1913) Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) Charles Lyell (1797-1875) My 16 candidates, 8 of whom* I have met Hewett Cottrell Watson (1804-1881) Edward Forbes (1815-1854) Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) Robert Lloyd Praeger (1865-1953) Francis Galton (1822-1911) *Henry Gleason (1882-1975) *Robert H Whittaker (1920-1980) *G Evelyn Hutchinson (1903-1991) Clement Reid (1853-1916) Alfred Gabriel Nathorst (1850-1921) Maria Stopes (1880-1958) *G Frank Mitchell (1912-1997) *Nicholas J Shackleton (1937-2006) *John Imbrie (1925-) *Derek Ratcliffe (1929-2005) *Daniel Simberloff (1942-) Between them, my 16 have made contributions not only to ecology, biogeography, palaeoecology or Quaternary science, but also to Deep-Time palaeobotany Other obvious candidates: *Stephen J Gould (1941-2002) Edward O Wilson (1929-) *Robert P McIntosh (?) *Cajo ter Braak (1954-) *Edward S Deevey (1914-1988) *Michael CF Proctor (1929-) *Robert M May (1938-) George Sugihara (1950-) *Mark Hill (1943-) *Frank Oldfield (1936-) Victor E Shelford (1877-1968) Have made major contributions to many fields including philosophy of science, mathematics, statistics, limnology, archaeology, world economic theory, bryophyte physiology, taxonomy, and literature as well as ecology, palaeoecology, quantitative ecology, or evolutionary ecology. Plan to discuss my 16 pioneering polymaths in a talk once a semester to try to answer for each • who were they? • what was their background/education? • what were their major achievements? • why should they be considered polymaths? • why are many of their contributions forgotten or ignored today? • how did they become polymaths? Some talks will be about one ‘mega’ polymath (e.g. Humboldt, Ratcliffe), while others about two super polymaths in related topics (e.g. Gleason & Whittaker; Imbrie & Shackleton; Hutchinson & Simberloff). Alternate ecology and biogeography (autumn) with palaeoecology and environmental history (spring). I hope to learn a lot in my reading and research – a journey through the history and development of our subject. Why discuss pioneering polymaths? “The past is essential – and inescapable. Without we would lack any identity, nothing would be familiar, and the present would make no sense. Yet the past is also a weighty burden that cripples innovation and forecloses the future. ... Growing awareness of an ever-expanding past coincides with modern efforts to destroy, to forget, and to make obsolete the legacy of all pasts.” David Lowenthal (1985) The Past is a Foreign Country Hewett Cottrell Watson Life and Relationships 1804-1881 Born in Firbeck near Rotherham, Yorkshire 9 May 1804 Died at Thames Ditton, Surrey (having lived there for 40 years) 27 July 1881 Contributed to phrenology botany plant geography* evolutionary theory 1839 Transformed Victorian wild-flower collecting in the 1830s into systematic botanical recording. Started the great tradition of such recording in Britain and Ireland that led to the Atlas of the British Flora (Perring & Walters 1962) and New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora (Preston et al. 2002), as well as of just about all living organisms in Britain and Ireland, all at 10 km grid square scale – bryophytes, lichens, fungi, butterflies, moths, gastropods, fish, amphibians and reptiles, mammals, birds, woodlice, centipedes, etc.! 1846 1871 No ordinary sedate Victorian botanist! Noted for his intellectual brilliance and cantankerous and difficult personality. Led an isolated and restricted life – never married and travelled only once outside of Britain to the Azores in 1842. “a turbulent figure, a born controversialist, a pungent critic, and a most enthusiastic disturber of the peace” Meikle (1949) Given his personality, not surprising he never received the academic recognition he deserved. Applied unsuccessfully or withdrew his applications for senior academic positions in London (Kings College 1842), Belfast, and Dublin (1846) and a senior position at Kew (1848). Yet Watson was the widely acknowledged authority on British botany and on the distribution of plant species in the British Isles. Despite his social isolation, had great command of the scientific questions of the day, including the importance of statistical methods in science, the asymmetric lateralisation of brain function and the transmutation of species in evolutionary theory. 1836 – published ‘What is the use of the double brain?’ which speculated about the differential development of the two human cerebral hemispheres 1844 – AL Wigan published his influential The Duality of Mind and ignored Watson’s work (Watson had clashed with Wigan!) Watson published 11 botanical books totalling over 4930 pages 29 papers on phrenology 310 papers* on botany 17 papers on climatology 6 papers on ecology 5 papers on plant evolution 4 papers on evolutionary theory (1832-1874) (1829-1840) (1830-1881) (1833-1839) (1833-1847) (1834-1847) (1845-1846) * includes many starting “Correction of a mistake in ...” Prolific, wide-ranging scholar but a difficult person Eldest son of Holland Watson Justice of the Peace, lawyer, and Mayor of Congleton in Cheshire. Mother Harriet Watson(née Powell) died when HCW was 15. Had 7 older sisters and 2 younger brothers. Terrible relationship with his father who was a reactionary, right-wing conservative and upstanding religious member of a fairly wealthy conservative society. Anti-trade unions – formed Stockport Volunteer Corps to break up meetings of workers! Watson was specially favoured in the family financially as he was the first son in a family that followed primogeniture, i.e. he inherited enough money to lead an independent life. He should have been happy; instead he was the unhappiest family member. He hated his father and felt totally out of harmony with his siblings – had almost no contact with them. “I never knew an individual towards whom I felt such a permanent and bitter antipathy as to my own father. We were totally unsuited to each other. My mother, a widely different character, died when I was fifteen, just when my fear of my father was changing into dislike and hatred. Ever since I have felt that my own mind and of course my life were very injuriously affected by him.” Watson (1848) Watson was the complete opposite to his father in politics and thirst for new knowledge. Mixed relationships with his mother – did not trust her as she ‘sneaked’ on him to his strict disciplinarian father. Watson’s only companions in his youth were their family gardener and Rev Dr Edward Stanley, rector of the neighbouring parish of Alderley (later Bishop of Norwich and President of the Linnean Society of London). Stanley was a substitute father figure for Watson. Wrote of his friendship with the gardener “this relationship probably contributed, in connection with my mother’s taste for floriculture, to give me a partiality for flowers; as a child at home, and subsequently as a schoolboy, was the chief amusement of my youth.” Watson (1883) And of Edward Stanley “During my schooldays a boyish fancy for plants and floriculture, which I had early inherited, attracted the favourable notice of Dr Stanley, whose opportune instruction and encouragement gave a scientific direction to the taste. ... The direction once given was never wholly lost, though discouraged in my own home.” Watson (1883) Watson’s hope of becoming a botanist active in the field were dashed when he was 15. He was hit on his right knee by a cricket bat and his knee joint was crushed. Never fully recovered full knee movement. Saved him from being sent as an Army Officer to the East India Company’s Regiment – his father’s sole ambition for him. This disability never really prevented HCW hiking or climbing mountains in Scotland or Mount Pico in the Azores. Probably main impact was emotional rather than physical. • Refused to go to Oxford to study classics and theology • Forced by his father to train to be a lawyer in Manchester in 1821 • Quit and moved to Liverpool in 1823 • Became interested in phrenology • Went to Edinburgh University in 1828 to study medicine • Became friendly with Robert Graham (1786-1845), Keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh from 1820. Major impact on Watson and on Scottish botany and horticulture • Entered an annual essay competition in 1831 with his entry ‘Geographical Distribution of Plants’ (discussed later) Also became friends with George Combe and joined the Edinburgh Phrenological Society George Combe (1788-1858) Watson inherited an estate in Derbyshire in 1828. Then moved in 1833 south to Thames Ditton on the railway near Kingston in Surrey, south of the River Thames and not far from Kew in central London. Lived there until his death in July 1881. Visited his three sisters occasionally in London. Joined the Linnean Society in 1834, but rarely attended meetings. Social recluse. HC Watson and Phrenology 1833-1840 Phrenology – pseudoscience focused primarily on measurements of the human skull – based on concept that the brain is the organ of the mind and that certain brain areas have localised specific functions or modules Developed by German physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828). Very popular in 19 th century 1810-1840 Main centre in Britain was Edinburgh. Edinburgh Phrenological Society founded in 1820 Gall 1805 Combe 1853 Fowler c. 1865 Now regarded as an obsolete mix of primitive neuroanatomy and moral philosophy. Phrenology was very influential in 19 th century psychiatry and continues to some extent in modern neuroscience and neuropsychology. The Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1826 had 120 members, over 30% with a medical background. By 1840, 28 phrenological societies in London with over 1000 members – medical doctors, social and asylum reformers, intellectuals (astronomers, politicians, authors, evolutionary biologists, geologists), etc., including HC Watson. Phrenology involves observing and/or feeling the skull to determine an individual’s psychological attributes. The founder Gall believed that the brain was made up of 27 ‘individual organs’ that determined personality, with the first 19 ‘organs’ believed to exist in other animals. Phrenologists would run their fingertips and palms over the skulls of their patients to feel for enlargements or indentations. May take measurements with a tape measure or a craniometer (special type of caliper). According to Gall, an enlarged organ meant that it was used extensively by the patient. 27 areas varied in function – sense of colour, likelihood of being religious, or destructive, or combative. Could allegedly judge a person’s personality and abilities! Combe wrote The Constitution of Man considered in relation to external objects (1828) – 19 th century bible of naturalism. One of the best-selling books of the century. Played a major part in 19 th century British cultural history. Sales of Constitution of Man (1828), Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844), and On the Origin of Species (1859) Combe’s Constitution was published 31 years before Darwin’s Origin. Generated huge controversy in Victorian society, just as Darwin’s Origin did 30 years later. The Church of England considered the book heretical and demanded its removal from libraries. Combe was considered an infidel. HC Watson became Combe’s disciple when he went to Edinburgh in 1828 to study medicine. Phrenology not taught at Edinburgh University or its medical school, but joined the Edinburgh Phrenological Society in 1829. Did well in his course but quit medical school because of poor health one semester before completing his degree in 1832. Decided that he would never practice medicine, even though he had been elected Senior President of the Royal Medical Society. Watson began in 1829 to publish in The Phrenological Journal (29 publications in total). After leaving Edinburgh in 1832, ceased to write scientific articles on phrenology but remained a staunch advocate. In 1836 published a major review of phrenology in British Isles In 1837 became editor of The Phrenological Journal hoping to raise its scientific standards. Wrote lofty and very critical editorials (a blog of the 1830s!), but his criticism and ridicule of articles submitted simply aroused anger in the authors and in 1840 he resigned as editor. Watson wrote in his resignation letter (9 August 1840) to the new editor Robert Cox that “circulation will increase more in your hands because you will give less offence.” Watson abandoned phrenology in 1840 and criticised it fiercely as pseudo-science or not even any type of science in correspondence with Combe until 1858 when Combe died. Also wrote to Darwin about it. “I have undertaken to assassinate phrenology” Last serious attempt to defend phrenology was W Mathieu Williams’s 1894 A Vindication of Phrenology Most interesting phrenological paper by Watson is 1833 ‘On the relation between cerebral development and the tendency of particular pursuits; and on the heads of botanists’ (Phrenological Journal 8: 97-108) Watson wanted to contribute to the development of phrenology as an aid in choosing a profession. He ‘discovered’ that botanists who “confined themselves to the relatively simple tasks of collecting, identifying and classifying plants” have well-developed ‘organs’ for individuality size locality language number i.e. systematists! Plant physiologists have large ‘organs’ for causality wit Ecologists – not a known word then, but Watson recognised a third (and highest) type of botanist that knew about environment, plant societies, and plant growth – have large ‘organs’ for comparison ideality or imagination Watson considered some botanists (and he named them) had particular brain ‘organs’ too small for the projects they attempted and their publications are correspondingly flawed! In his own autobiographical sketch (1883), Watson’s cranial characteristics showed he belonged to the ‘environment’ or ecology category. Should not look too closely at Watson (1833). Only had 12 botanists heads, but he concluded that “the average of botanical heads is smaller than would be found in those of several other sciences, as Geology, Moral Philosophy, Natural Philosophy or Political Economy.” Basic data of Watson (1833) when analysed by Marti Anderson’s non-parametric MANOVA show no significant difference between sciences! Also investigated in 1831-32 brain ‘organs’ of vegetarians, ‘super-vegetarians’ (Victorian term for vegans), and non-vegetarians at the time before the creation of the Vegetarian Society in 1847. Concluded some differences and generated much controversy as the vegetarian movement was still developing at that time. The ‘organs’ that Watson thought were well-developed (sensu Combe 1851) in vegetarians were secretiveness cautiousness individuality causality combativeness 2007 Phrenology in one form or another has never really died out • used to explain so-called superiority of certain races • used as an obstacle to anti-slavery movement in southern USA • is a personal service today in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota and subject to sales tax (MVA)! But Watson left it all behind in 1840 and concentrated on botany instead HC Watson and Botany 1830-1881 In 1831 won Gold Prize for his essay on ‘Geographical distribution of plants’ awarded by Robert Graham in Edinburgh. Amazing essay by a 27year-old who had never studied botany seriously. Greatly influenced by Humboldt’s (1816) ‘Prolegomena’ in Nova genera et species plantarum and John Linley’s (1830) Introduction to the natural system of botany. Humboldt provided general laws; Linley provided geographical ranges and the extent of each plant family within a region. Watson brought them together for the first time. Watson’s essay is in two parts (copy at RBGE) 1. Divided world’s flora into six latitudinal zones and described the now well-known parallel between latitudinal and elevational ranges of species. • Arctic species of different continents more similar than temperate species. • Temperate species have a more northern distribution on western oceanic coasts than on eastern continental coasts due to differences in temperature. • Flora of eastern Asia resembles flora of eastern North America. • Flora of western Europe resembles flora of western North America. 2. ‘Conditions of vegetation’ discussed temperature, moisture, soil, and minor factors. • Water was most important physiologically but temperature had most influence on species distributions. Water was clearly dominant factor for aquatic and desert species • Since many species grew in different kinds of soil, then moisture, temperature, soil texture, and organic content were more important that soil chemical composition. Exceptions were Ophrys orchids confined to chalk soils and Erica vagans confined to serpentine soils • Shade, animals, humans, wind, and disturbance were ‘minor environmental factors’ Remember this was written in 1831 – 182 years ago! Well before ecology and evolutionary biology or biogeography were recognised as subjects. Ecology 1866 Haeckel Left Edinburgh in 1833 for Thames Ditton. Had failed to form an Edinburgh botanical society. One was founded in 1836 by a group of botany students including Edward Forbes (founding father of marine biology in Britain and victim of Watson’s criticisms). Watson joined in autumn 1836. It became the Botanical Society of Edinburgh, and subsequently the Botanical Society of Scotland – still alive and well. Also in 1836 Botanical Society of London founded. Originally called the Practical Botanists’ Society of London – practical to refer to people who ‘got their hands dirty’ as opposed to merely professing botany. First scientific society in Britain to admit women as members. Watson joined BSL in 1840 and was instantly made Vice-President (but never President!). Also curator as it quickly became the Botanical Exchange Club – exchanging specimens. Replaced in 1947 by the Botanical Society of the British Isles – also still alive and well. Auction of the BSL herbaria in 1857 20 Bedford Street, London – BSL HQ In 1832 instead of taking his final medical exams he wrote his first synthesis of the British flora – and really started plant geography in Britain – Outlines of the Geographical Distribution of British Plants (334 pp) Much narrower in scope than his 1831 essay that had primarily been a literature review of the world. The 1832 book was totally new, modelled in part on Wahlenberg’s three amazing regional floras (1812-1814) Flora Lapponica, De Vegetatione et Climate in Helvetia Septentionali, and Flora Carpatorum. Part 1 – general discussion Part 2 – for each species, details of habitat, elevational range, and world distribution • listed what were likely to be introduced species, mainly from ship ballast • climate data for 530 localities for mean annual, winter, spring, summer, and autumn temperatures, hottest and coldest months, annual rainfall, and elevation (very Humboldtian!) • divided British vegetation into three broad regions, each of which was divided into two elevational zones. These 3×2=6 zones summarised for Britain what he had in his essay on world flora and vegetation. I II III Region Zone Indicator species limit Woody 1 Agricultural Wheat cultivation ceases 2 Upland Coryllus avellana ends 3 Moorland Carex bigelowii starts 4 Subalpine Calluna vulgaris ceases 5 Alpine Empetrum nigrum ceases 6 Snowy No land! Barren Mossy Became obsessed with 6 zones. Did not understand the distinction between observable facts of nature and empirical systems of convenience. Led to a bitter dispute with Edward Forbes, early vegetation historian, biogeographer, and founder of marine biology in Britain, who proposed that there were five zones not six! 1832-35 HCW became more interested in elevational ranges and temperatures. Wanted to relate distributions and climate. Found same species occurred at different elevations on different mountains. “Absolute altitude is of little importance in the geography of plants and therefore my attention is for the most part limited to the observation of their relative height in regard to each other.” Watson (1832a) Upper limit (feet) Species Clova Braemar Fort William Tongue Erica cinerea Ulex europaeus 2400 2200 2100 1730 1500 1350 280 350 Watson emphasised importance of ‘situation’, namely slope (angle) and aspect (direction of slope) “The influence of situation is well exemplified by the fact that Empetrum nigrum, under the steep snow rocks on the northern side of Ben Nevis fails 600 feet below its height on the western side.” Watson (1832b) Wrote 7 articles based on his Humboldtian-type studies. His 1833 paper on ‘Observations of the affinities between plants and adjacent rocks’ (Magazine of Natural History 6: 424-7) was so ahead of its time in considering environmental complexes (and so almost totally unknown) that Eville Gorham published a note about it in Ecology in 1954, thereby helping to prevent ‘ignorance creep’. Watson emphasised “It is necessary that all conditions of vegetation be studied in connection. He who neglects any will so far fail in his generalisations.” Presented six main conclusions. 1. Rank of importance of factors are temperature; moisture; situation; mechanical and chemical properties of surface soil; mechanical and chemical properties of underlying bedrock. 2. Combined influence of these determines flora and vegetation of counties (cf. 1831 essay). 3. Factors not always in equal ratio. When temperature is best suited for a species, soil is of little importance. When temperature is marginal, soil factors more important. 4. Temperature effects shown in flora of a county (regional scale). Other conditions may not affect the flora of a large area but other factors modify the vegetation (local scale). 5. Comparing species, some are more influenced by one factor, others are influenced by other factors. 6. Influence of bedrock is so frequently hidden by other conditions that the flora of a county is not obviously affected by it, but vegetation of smaller areas may be influenced by underlying geology. In 1835 published Remarks on the Geographical Distribution of British Plants; Chiefly in Connection with Latitude, Elevation, and Climate (288 pp). No new insights, but much new data. 1835-37 The New Botanist’s Guide to the Localities of the Rarer Plants of Britain; on the Plan of Turner and Dillwyn’s Botanist Guide. Volume 1: England and Wales, Volume 2: Scotland and Adjacent Islands (674 pp) Update of Turner and Dillwyn’s (1805) The Botanist’s Guide Through England and Wales (2 volumes) Very detailed account of localities. Strong attack on British botany at that time, hence The New Botanist’s “British botany is in danger of degenerating into a sort of outdoor (and indoor) game, with pretty pictures, simplified texts, ferns, and portfolios, and melodious twitterings from the pens of Mr Edwin Lees and the gifted Miss Twamley – just the right kind of thing for the poetic young man or the refined young lady, with nothing technical or scientific to mar the pleasures of a gentle sport.” Watson (1835) Watson forced his disturbing ideas and argumentative character into the gentle activity of British botany in 1832 and 1835 but this was just the beginning! In 1835 Watson emphasised that British botanists could not even agree on how many species there are – 1500 to 1636. Watson, ignoring doubtful claims, counted 1400. Stace (2010) has 1421 native species. Darwin liked Watson’s comments about species number and repeated them in On the Origin of Species. Watson also estimated that every British county contained 50% of the British flora and that a square mile of a county generally contains half of the species of a county – i.e. species-area relationship. Joseph Hooker was amazed at this and told Darwin (28 September 1846) who was fascinated. Watson followed this idea up in 1847 (not 1859 as Rosenzweig says). Rosenzweig 1995 Connor & McCoy (1979, Am Nat) has correct references to Watson (1835, 1847). Log species – log area plot Arrhenius (1921) or y = axn where y = number of species, x = area, a = constant Dony (1963) “Watson was as near the truth as anyone has been or is likely to be.” Watson was thrilled by “the lofty peak of Pico, rising high and sharp into the deep blue sky, with a wreath of white clouds” (Mount Pico or Ponta da Pico) Ulrich Thumult In 1842 he was a botanist on naval expedition to map the Azores. Captain Alexander Vidal (17921863) commanded the steamer Styx. No Humboldt disciple could resist climbing Pico. Major climb (2351 m). Watson recorded upper elevation limits of many plants – strawberries, figs, oranges, vines, apples, yams (Caladium), Laurus, Myrica faya, Erica scoparia, and Juniperus ?communis. Upper vegetation Scirpus, Carex, Callitriche, Peplis portula, Potamogeton natans, Calluna vulgaris, Thymus caespititius, mosses, and lichens. Barren peak at 2351 m. Pico’s extinct crater was “a natural botanic garden where the true flora of the Azores, above the cultivated region, reigns undisturbed” Watson (1843-47) Visited four of the ten islands. Collected plants including the new Campanula (Azorina) vidalii and Myosotis azorica Watson disappointed that he found fewer species than expected (“scarcely 300”) given the range of elevations and climates. Twelve genera endemic. Compared Azores flora with that of Madeira Thought Azores Vaccinium cylindraceum and Madeira V. maderense to be varieties of same species. Characteristic Watson “Those botanists who delight in multiplying species on paper, by describing extreme forms, in disregard of intermediate and connecting links will doubtless keep them distinct.” (Watson 1843-47) A ‘lumper’! Frederick DuCane Godman (1834-1919) went to the Azores in 1860s to collect plants and animals. Wrote a collaborative Natural History of the Azores (1870). Watson contributed a mere 175 page account of the flora, now 478 species, with occurrences in Europe, Madeira, Canary Islands, America and Africa. 40 were endemic. Used his data in an early island biogeographical context to test Edward Forbes’s (past ‘friend’ and constant combatant) hypothesis that Azores were remnants of a former continental extension with Europe. Falsified Forbes’s hypothesis – first such hypothesis testing in island biogeography. Also used his data to test Darwin’s ideas on origin of species. Found some counter-evidence but concluded that positive, supportive evidence for Darwin’s ideas was stronger (Watson 1870). In 1843 published The Geographical Distribution of British Plants Part I (3 rd edition), 259 pp. Decided it was too detailed, so started a simplified version! 1847-59 and 1860-74 Cybele Britannica: or British Plants and their Geographical Relations (4 volumes, over 900 pp, plus 2 supplements and 1 compendium in 1870 of 650 pp.) Documents the distribution of British flora more precisely than anywhere else – tradition continues to the present day. Mapped 18 provinces in volume 1; subdivided them into 38 sub-regions, and 120 counties and vicecounties in volume 3. Vice-counties were created to all be of about the same area to allow comparison of species richness between counties. Watson’s vice-counties alive and well today, along with 40 in Ireland and Channel Islands. Used today for plant recording, especially bryophytes and lichens. Once a keen vice-county ‘bagger’ of new bryophyte records! For each species lists • number of provinces (18) • ranges of latitude, elevation, and mean annual temperature • geographic status native denizen (naturalised) colonist (casual) alien incognita (needing confirmation, status unclear) • habitat (15 types) His distribution of five types of geographical status was the first attempt to codify nativeness. Recently recognised as a great pioneer in invasive biology. Predecessor for Mark Hill et al.’s PLANTATT (2004) and BRYOATT (2007). Watson (1859) Hill et al. (2004) Watson’s Cybele Britannica also has important chapters on ‘On orders, genera, and species’ including a discussion of permanence of species ‘On the introduced species’ ‘Physical geography and climate of Britain’ ‘Altitudes of species’ and ‘General remarks’ which includes the first phytogeographical analysis of the British flora and of any country’s flora. First serious attempt to put British plant geography on an exact scientific basis. Replaced vague generalisations with concrete facts. Analysed the composition and character of the flora. Bad reception – title was unpronouncable, no pictures or poems, nothing to please the “botanical dabbler”, nothing but facts, figures, statistics, names, and numbers. Anonymous hostile review in The Gardener’s Chronicle (1859) edited by John Lindley (17991865) Professor of Botany, UCL. Acknowledged Watson’s enormous labour but dismissed the results as of no consequence. “Instead of precise results we have elaborately learned disquisitions, which really, when dissected, end in nothing.” Anon (1859) (Identity revealed by Hooker to Darwin in 1859 who subsequently told Watson. Watson responded with severe sarcasm in the First Supplement) A previous fierce 22-page review in 1854 was by zoologist Rev John Fleming (1785-1857). Showed Fleming was not a competent botanist but a good friend of Edward Forbes! “Cybele is scarcely more than a mechanical operation, conducted, however, by one to whom the subject was familiar in all its bearings.” Fleming performed what he called his ‘Christian duty of being a peacemaker’ by mentioning Forbes’s praise of Watson but remained silent about Watson’s attack on Forbes. If Watson read all this, he did not respond – most out of character! Watson “never recouped himself one penny of the cost of paper, print, and binding” despite “[Contributing] more to British botany than all the outpourings of poetic-floristic flummery put together.” Meikle (1949) 1873-74 Watson continued to collect plant geographical data and refine the precision of his species accounts. Published Topographical Botany (740 pp) and was working on a second edition when he died in 1881. JG Baker (1834-1920) and WW Newbould (1819-1886) published it in 1883. On his death, JG Baker was left Watson’s house and land, his books, letters, and herbarium collections. Baker had persuaded Watson not to burn his herbarium (now at Kew in Watson’s cupboard half-way up the stairs in the Kew Herbarium). All his notes were burnt. “After hurriedly writing Topographical Botany, while the data still existed, I burnt (inter alia) a whole wheelbarrow full of botanical correspondence. This was done in order to spare my Executor the tedious trouble in having to go through such a mass of letters and papers in order to select such as might seem to him needful to keep a while longer.” Watson (7 April 1878) Large leather-bound books in which all the vice-county records were entered survived and are now in the Kew library. Watson, Darwin, and Evolutionary Biology 1834-1881 Watson interested in plant evolution and corresponded frequently with Darwin. Reacted to Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology (1832) in which Lyell discredit’s Lamarck’s transformation of species. Watson was, even at an early age, convinced evolution occurred but not as Lamarck proposed. “Species in any sense or degree I look on as human divisions, not creations of nature. The changes, proved by geological evidence, to have occurred in organic forms, and those now effecting by climate, elevation, crop-breeding, etc. etc. strongly discountenance the idea of absolute and permanent distinctions.” (7 Oct 1834) In 1845 huge dispute between Watson and Edward Forbes (1815-1854) ecologist, botanist, marine zoologist, ‘bio-geologist’. Died age 39. Forbes in a lecture in 1845 synthesised what was known about Quaternary flora in relation to modern British flora and suggested that there were five sources of British plants. 1. Irish region - ‘Asturian’ flora 2. South-west Devon - ‘Norman’ flora 3. Kentish flora - ‘French’ flora 4. Alpine or ‘Scandinavian’ flora 5. Central European – ‘Germanic’ flora Published major monograph in 1846 ‘On the connexion between the distribution of the existing fauna and flora of the British Isles and the geological changes which have affected their area, especially during the epoch of the Northern Drift’ Watson furious – he had six regions, Forbes had five! Accused Forbes of ignoring his work of 1832. Checked with Linnean Society Library and found that Forbes had checked out his 1832 book before his 1845 lecture. Forbes gave Watson generous acknowledgement in his full 1846 paper, but Watson was not satisfied. Darwin was interested in Forbes’s ideas and they corresponded. Darwin could not follow Forbes’s arguments so he consulted Joseph Hooker. Hooker too was sceptical. “This fracas between the 2 geographers distresses me, for they are almost only the 2 men who have looked on British flora with the eyes of philosophers. Watson in particular ranks in my opinion at the very head of English botanists, whether for knowledge of species or of their distribution.” (3 Sept 1845) “I have not seen Forbes since studying his paper & really do not know what to say when I do, for most unfortunately he does not seem to know the Geographic Distrib. of the English plants.” (28 Sept 1845) Darwin was friends with Forbes before this incident. This conflict and his friendship inhibited Darwin from contacting Watson directly until Forbes died in 1854. “What makes Watson a renegade” (Hooker to Darwin, 27 June 1845) Whilst Forbes was alive, Hooker acted as intermediary between Darwin and Watson. Watson wrote “You take with sufficient good temper the circumstance of a botanist siding with the Enemy” (1849) Darwin wrote to Hooker about Watson’s paper (184347) on the Azores – thought it was strange that there were so few ‘peculiar’ species or forms and so few species on the summits. Darwin wanted a comparison with Madeira, Canary Islands, etc. Watson provided all this in his 1870 chapter. Watson studied hybridisation (e.g. Primula vulgaris, P. elatior, P. veris) and species with dimorphic ‘unstable’ flowers. In 1845 presented his ideas on evolution in an extended review of Robert Chambers (an evolutionary phrenologist) Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (1844). Watson’s review was in four parts! Showed evolution was a reasonable interpretation of Chamber’s evidence but Watson wrote “while the species is kept up by some more fortunate or favoured individuals, a vast number of individuals die prematurely.” Although Hooker saw Watson’s review and follow-up articles, he apparently did not read them. He reported to Darwin that Watson is “an avid believer in Progressive development, as enunciated & upheld in the already defunct ‘Vestiges’.” – Incorrect! On 7 April 1847 Darwin asked Hooker for information on “cases of varieties between two other varieties being rare”. Hooker then asked Watson and Watson sent him a 124-page account which Darwin annotated for later use. Watson had done garden experiments in 1841 with 88 plants of three Primula species. Looked greatly at variation and hybridisation. Cultivated may varieties in his garden to study – phenotypic variation. Concluded to CC Babington “no eternally permanent species exists.” (1845) Charles Lyell in Principles of Geology (1830-33) cited Watson and JS Henslow’s conclusions as evidence that the existence of varieties in nature is no evidence for the transmutation of species. Watson knew about the fossil records and was struggling in 1845 with an explanation for the facts except transmutation. “The supernatural alternative is the one generally received by the vulgar, and admitted – tacitly, at least – by men of science.” “The stone tablets of Geology make transmutations seem inevitable, I doubt if these tablets will ever reveal how it happened.” Darwin clearly respected Watson and in Darwin’s huge manuscript on ‘Natural selection’ begun in May 1856, Watson was cited 27 times. The 692-page ms not published until 1975 – victim of circumstances. Alfred Russel Wallace sent Darwin his manuscript on natural selection in 1858. Joint reading of their papers at Linnean Society. Darwin trimmed his ‘Natural selection’ into a 502page more readily publishable On the Origin of Species (1859). Cited Watson 8 times and wrote “Mr HC Watson, to whom I lie under deep obligation for assistance of all kinds.” Darwin sent Watson a copy of Origin. Watson responded “Once commenced to reading the ‘Origin’ I could not rest till I had galloped through the whole. ... You are the greatest Revolutionist in natural history of this century, if not of all centuries.” (21 November 1859) Despite living 18 km away from Darwin’s Downe House, Watson never met Darwin. Declined an invitation to discuss evolutionary ideas with Darwin and Hooker in 1859 – Watson was too busy and did not wish to travel. Watson very much a social recluse. Legacy 1. Started systematic plant recording. BSBI, BBS, BLS, Atlas Flora Europaeae, etc mapping schemes 2. Watsonian vice-counties 3. Species-area relationships (Surrey) 4. Hypothesis-testing in island biogeography (Azores) 5. Phytogeographical analyses, concept of multifactorial control of plants, appreciation of geographical scales 6. Many publications – 11 books, 370+ papers 7. Contribution to invasion biology – different types of geographic status 8. Initiated ‘garden experiments’ and ‘experimental taxonomy’ Because of his abrasive personality, only one species named after him Eleocharis watsonii (slender spike-rush) now called E. uniglumis BSBI started its journal in 1949. By a close vote (9 for, 7 against) it was called Watsonia Then in 2010, title changed to New Journal of Botany at request of publishers. No-one, they argued, know who Watson was! Not commercial or catchy enough. Probably one of Britain’s greatest botanists Very appropriate that a ‘blue plaque’ was unveiled in 2012 to commemorate Watson’s birthplace in Firbeck, near Rotherham. One is left wondering how such a polymath and workaholic could do so much and contribute original ideas and data to so many fields. How was it possible to do all this in the 1850s? Was his difficult personality an advantage or disadvantage? Watson was five years older than Darwin – both had developed within the same scientific environment phrenology evolutionism Humboldt’s environmentalism Lyell’s uniformitarianism British naval exploration Growth of scientific institutions Professionalisation of science Watson certainly as important in British botany as William Hooker (1785-1865) and his son Joseph Hooker (1817-1911) William Hooker (1841) HC Watson (1846) Joseph Hooker (1870) The Hooker’s association with Kew and moderately pleasant personalities ensured that their work is well-remembered. Watson with no institute and a difficult personality ensured that his work is barely remembered. “intellectual truth should be held paramount over all other considerations” Watson (1883) A view we will see repeated with other pioneering polymaths – Gleason, Whittaker, Simberloff, Ratcliffe, Imbrie, Shackleton – all of whom changed our views on ecology, environment, and the world, and how we should do science.