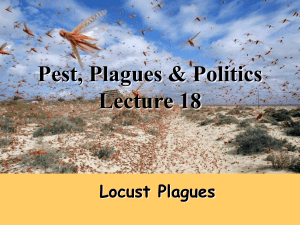

Locust Swarm behaviour Presentation

advertisement

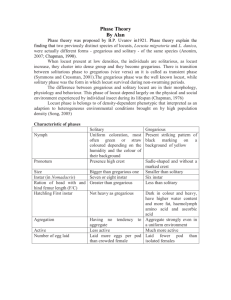

Collective Locust Swarm Behaviour and the Environment • When environmental conditions are favorable locusts breed rapidly greatly increasing their population numbers • They first form bands as nymphs and then after 5 molts as adults they can form Swarms • These swarms have been known to cover hundreds of square miles and contain up to a billion locusts • The collective behaviour of swarming in locusts is largely affected by 1. The Landscape 2. Favorable environmental conditions (Rain, Temp) 3. Availability of Food which is all related to the survival of the young The Effects of Landscape • Desert locusts Schistocerca gregaria outbreaks consistently start in the same place according to historical records which suggests that certain landscapes particularly favour outbreaks. • High resource abundance promotes locust multiplication and the contraction of resources into small patches increase concentration. The effects of ecology • High nitrogen levels: a faster development, higher survival, reproduced more and earlier and also showed a greater synchronization which is key to the collective swarming behaviour. • Low Nitrogen Levels: active and passive cannibalism but this was not found in those that were fed with the higher nitrogen level leaves. • Overall, this shows that the nitrogen content of the host plants in the landscapes that the locusts dominate affect the potential for population increase The effect of nitrogen Sequence of Rainfall • Spur throated Locust: • Adults lay eggs in early wet season: >40mm rainfall needed for oviposition Another >40mm rainfall needed for survival • D. M. Hunter (1999): populations increase more than 50% when receive intial and two or more follow up rain intervals of less than 6 weeks • Bullen (1969) showed that many of the plagues between 1935 and 1968 began in year where there was above average rainfall following drought “Locust swarms are spectacular and damaging manifestations of animal collective movement” J. Buhl et al. (2011) Shapes, Dynamics and Behaviour • Types of swarm: I. Columnar II. Frontal structures Australian Plague Locust (Chortoicetes terminifera) Desert Locust (Schistocerca gregaria) Rhammacocerus schistocercoides Frontal structures: • Highest concentration of locusts at the front • Exponential decay of density as one moves towards the back • Front forms a thin crescent shape where densities can reach several thousand individuals per square metre and the rest of the group behind this are scattered. High Density Effects Temperature Affects Density Alignment 13.5cm • Less than 13.5cm showed high proportion of individuals were moving in the same direction • Greater or equal to 13.5cm showed range of differences in polarity The influence of spatial scales, Collett et al 1998 • Local spatial concentration of resources induces gregarization • Uneven resource distribution – crowding – increased gregarization • Positive feedback for behavioural change • Mean contact threshold for gregarization in locally concentrated habitats Collective motion and cannibalism in locust migratory bands (Bazazi et al 2006) • Cannibalistic interactions influence Mormon cricket migrations – general principle? A) Abdominal denervation • decreased detection of individuals from behind • Decreased probability of starting to move • Decreased proportion of mean number of moving individuals • Increased cannibalism • No influence on behaviour of isolated locusts Mean proportion of moving locusts comparison of sham-operated controls and denervated individuals b) Restricted visual fields using black paint. Lower proportion of moving locusts in back-blind compared to front-blind individuals • Within groups, abdominal biting and sight of others approaching from behind triggers movement • Autocatalytic feedback - > directed mass migration • Balance between minimising your own risk from cannibalism and allowing attacks of others Questions?