romania - The language of art

advertisement

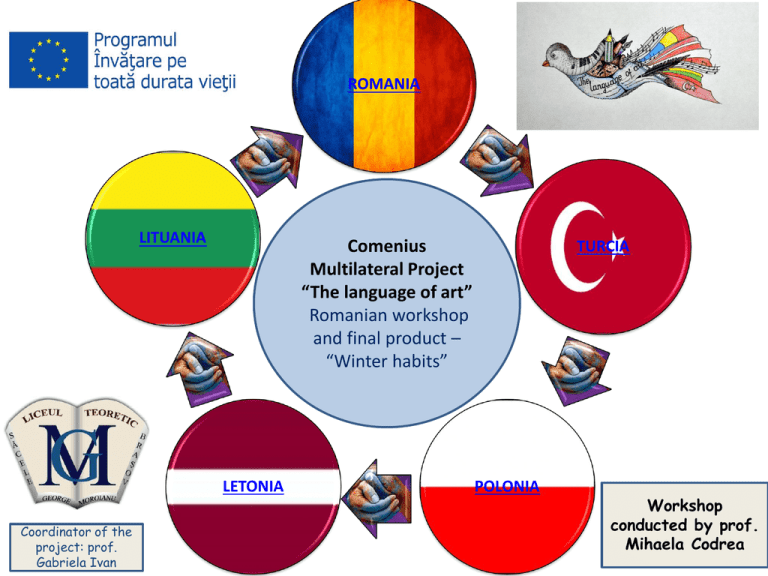

ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea DOMANTAS DOMINYKAS ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea BURAK OZDER ALY SED ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea MARAMURES ELENA& PAUL BUCOVINA ADINA BANAT STEFANIA TRANSILVANIA EDWARD DOBROGEA TEODORA THANK YOU FOR YOUR COOPERATION! Winter habits from Poland Poland ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Winter habits from Latvija. Latvija ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Winter Habits From Lithuania Lithuania ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea ‘’Winter Habits of Lithuania’’ Lithuanian traditional costumes ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Turkey Moschee – Loc pentru rugaciuni Durum Costum Traditional Baklava ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea WHINTER HABITS FROM TURKIE TURKEY ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Winter habits from Turkey chestnut boza ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea WINTER HABITS FROM ROMANIA ROMANIA-Maramures ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea WHINTER HABITS FROM ROMANIA ROMANIA -MARAMURES ENGLEZA ROMANA ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Christmas customs and traditions are still alive in Maramures Christmas continues to be a celebration Maramures where traditions and customs are kept religiously, it can best be seen in the villages. And in big cities but on Christmas Eve but you can see groups of singers, young and old, going to proclaim to friends Nativity. People spend with family and friends three days in one. Christmas does not mean only three days, called "the Christmas village." Celebration has three stages: preparation period, fasting and all other actions in entering the house cleaning, the yard, graves, then there is the period between December 23 (Eve Eve) and January 31 and the last is the period of the New Year ( The little old named Christmas) and Epiphany. Maramures is still a place where you can hear the voices of children and young people and the elderly who proclaim the birth of Jesus, but first of all ask: “Leave them to wander?". Delia Suiogan PhD lecturer at the University of Baia Mare believes that as long as carols and carols will never perish, Christmas celebrations will not lose its charm in Maramures. "Carols in common is an ancient ritual magic symbols with very complex functionality. Ceremony includes elements of sun worship, worship of the dead elements, and elements of worship agriculture, "said anthropologist specialist. "Star" and "The Goat" fun cocoons Christmas Eve in Maramures villages are the first to go trick or treating children. With traditional purses, they go on to houses to announce the grand event will occur, and in return their carol use to provide coins, nuts, apples. The walk to the "Star" or the "Goat", whose game (killing, bocirea, burial, resurrection) originally was a serious ceremony. Delia Suiogan showed that goat parade of characters Dionysian procession reminiscent of half man, half animal encountered in Thracians, the Greeks and the Romans. Children are objects made of time necessary, improvising with what they find in the drawers mothers, especially the "star" that go trick or treating should be really bright and "goat", as luscious and loud. In some areas outside these traditions are preserved and "Viflaimul", a popular theater that arise that relate biblical Nativity time. There are few villages in Maramures who presented the show, and the large number of characters, over 20, and the careful preparation to be made well in advance. In Ieud, but also in other places of the Iza Valley tradition was preserved, even if "Viflaimul" is presented just before Christmas. "The game estates," the art of disguise Delia Suiogan showed that "the holiday season, a role it has played and still plays disguise and travestirea May practiced at playing with masks. Those who mask, individually or in groups, watching that besides frames of the project to obtain real or magical, using masks and spiritual connection with alleged superhuman strength. " It showed that "mask wearer is mindful of its power is removed from profane time and space" and "Joker mask retains function with intent to secure the passage she wears easier than" thresholds "that to be overcome, because the mask implies a series of prohibitions, but it will also give the right to a behavior that comes from daily patterns, real soon. " She added that in Maramures, a particularly important place in our game Mosilor years, the origin of which seems ceremonies with masks stood vigil nights - ancestral ritual of honoring the dead. "The actual mask made of fur mos Maramures cattle, although reminiscent of animal origin similar mask differs from the rest of the country through ethnographic areas that do not have horns," said Delia Suiogan. According to the game Mosi is a special moment and is distinguished by the ingenuity of those who knock on doors and hosts disguise to scare them and wish them happiness and health. Colacutul gave singers, a symbol of the sun. Ethnologist said that they have an important place and wandered about objects, reminiscent of beat, which is seen as a "tree of life". Reaching goals, and the women, and repeated beating both floors of the house and in the yard with bat ground fertilizer acts according beliefs of Maramures. Also, another ritual object that is missing from Maramures Christmas households is hoop, which is a symbol of the sun, proofing dough which is signifying fertility. There are but apple - sacred food "fruit of knowledge", and walnut, which is assimilated and "cosmic egg". All these can be found on Christmas tables all households in Maramures, even if modernism has made its way even in rural areas. "All symbols used by actantial rituals or gestural nature, object, or animal or vegetable etc. are designed to recreate the myth (at the originating or the Christian Creation). Nothing is accidental, everything is subject to the order established by mythical memory. Celebration of Christmas or the New Year and beyond, are a form of direct participation in the cosmic order, "said Delia Suiogan. She admitted that habits were "reworked" regular community members. Christmas superstitions have their place on holidays. Are therefore extremely rare situations where floors are covered with fresh hay house, and under the tablecloth is made straw for acquiring wealth. Also chains no longer bind with table legs, custom is practiced to stop wild animals attacking cattle in yards and to remove evil from the house. But superstitions persist, so do not give the mature Christmas, no laundry and not give anything lender. Also, give saturated animal food in the household, including a piece of yeast dough, which is believed to protect them from diseases. In some areas, it is said that if Christmas Eve, the animals rest on the left, is a sign that winter will be long and very cold. There is also the belief that those who complain will complain Eve all coming year and Christmas morning you should wash your face with spring water that put a silver penny. Christmas preparations are required in Maramures and the peasant take this opportunity to reveal to her their heritage or married girls. Sterguri beautifully woven, embroidered pillows painstakingly dressed in girls, colorful rugs are removed from the cabinet and placed in rooms, especially the carol singers are received. Houses not miss any tree, now decorated with lights and ornaments Chinese and sometimes with nuts, apples or rows of white beans instead of tinsel. Christmas dinner, magical moment of celebration. The most important is that the Christmas house is clean and decorated holiday and table is full, that family gathering around the table and the tree is the most well preserved. Delia Suiogan showed that "habit is a form of reconstruction of the house gathering all around logs illuminates the sacred hearth Eve house and has a sense of power load with the participants". In fact, even many believe that Christmas Eve is not allowed to put out the fire in the stove, so that the man of the house used to put the fire a large stump. Delia said Suiogan gathering around the table for Christmas recipes "return to the circle, which could be interpreted as a form of initiation or restarted. Starting from the center "cool" enable reconstruction own "center", so that every home is a repeat of "Center of the World", participants with the opportunity to charge with power. " As for the feast, it is to provide welfare, but is also a form of sacrifice: the pig for cooking sausages and caltaboslului, and the grain of wheat to make bread. Rituals for health and family welfare Delia Suiogan also said that "many rituals were preserved. Some felt that habits are not being treated as ordinary shares, but part of that long series of symbolic gestures that allow the individual to periodically have the chance for a new beginning. " She gave the example of Costa Brava, which is felt today as a very important ritual gesture of recalling the sacrifices to gods who were born and dying regularly in renewal periods of calendar time. His sacrifice was made before a certain day, the Ignat and dawn. Even if time is no longer observed, it still retains a series of rituals that are meant to provide health and family welfare in the New Year. Thus, the pig should not whine and all activities during his cutting must be accompanied by good vibes and wishes. "In Maramures crossed the blood is on top of cocoons (No - children) that they are healthy and strong. Contact with animal flesh, its blood implicitly means the transfer of power, the life of those who consume this food. At the same time, the animal becomes mediator between worlds, between man and god / deity, between man and his ancestors, "said university lecturer. Carol, a possible "key" to the gates of knowledge Christmas in Maramures identify the carol, which, despite pressures on folklore, not "manelizat“ but was preserved as sung by the ancestors. Ethnologist believes that "as long as it will not resort to miming and free Christmas will remain the same, a time of joy and rebirth", adding that he would like that to be celebrating five years as beautiful now, although fears that "could result in loss of identity within globalization the phenomenon of disintegration". "Rediscovering the true meanings of gestures or objects may contribute to maintaining tradition. Thus, caroling ceremony related to joint appeal to a range of objects loaded with meaning and value, just because of their function as a mediator between man and nature, between man and cosmos. They are not mere objects become forms of communication between worlds. Carol can receive and purpose of indicating direction, becoming a possible "key" that opens her gates to being some knowledge "concluded ethnologist. MERRY CHRISTMAS! ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Craciunul continua sa fie in Maramures o sarbatoare la care traditiile si obiceiurile se pastreaza cu sfintenie, cel mai bine acesta putand fi vazute la sate. Si in marile orase insa, in Ajunul Craciunului se pot vedea insa grupuri de colindatori, tineri si batrani, care merg sa vesteasca pe la prieteni Nasterea Domnului. Lumea petrece impreuna cu familia si prietenii trei zile intr-una. Craciunul nu inseamna insa doar cele trei zile, numite «ale Craciunului satul». Sarbatoarea are trei etape: perioada de pregatire, postul si toate celelalte actiuni in care intra curatirea casei, a curtii, a mormintelor; apoi mai e perioada cuprinsa intre 23 decembrie (Ajunul Ajunului) si 31 ianuarie, iar ultima este perioda dintre Anul Nou (numit in vechime Craciunul cel mic) si Boboteaza. Maramuresul este inca un loc in care se pot auzi glasurile copiilor si tinerilor, dar si ale celor batrani care vestesc Nasterea Domnului Iisus, dar intai de toate intreaba: “Slobodu-i a colinda?”. Lectorul universitar doctor Delia Suiogan de la Universitatea de Nord Baia Mare este de parere ca atat timp cat colinda si colindatul nu vor pieri, sarbatoarea Craciunului nu isi va pierde farmecul in Maramures. ”Colindatul in comun este un ritual stravechi cu functionalitate magico-simbolica foarte complexa. Ceremonialul contine elemente de cult al soarelui, elemente de cult al mortilor, dar si elemente de cult agrar”, a precizat specialistul etnolog. ”Steaua” si ”Capra”, distractia coconilor In Ajunul Craciunului, in satele din Maramures primii care pleaca la colindat sunt copiii. Cu traistutele prinse de gat, acestia merg pe la case ca sa anunte marele eveniment care se va produce, iar in schimbul colindei lor se obisnuiste sa se ofere colacuti, nuci, mere, iar acum, din ce in ce mai des, se dau bani. Se umbla cu ”Steaua” sau cu ”Capra”, al carei joc (omorarea, bocirea, inmormantarea, invierea), la origine, a fost un ceremonial grav. Delia Suiogan a aratat ca alaiul caprei aminteste de alaiul dionisiac al personajelor jumatate om, jumatate animale intalnite la traci, la grecii antici si la romani. Copiii isi confectioneaza din timp obiectele necesare, improvizand cu ce gasesc prin sertarele mamelor, mai ales ca ”steaua” cu care se merge la colindat trebuie sa fie neaparat stralucitoare, iar ”capra”, cat mai inzorzonata si galagioasa. In unele zone, in afara acestor obiceiuri se mai pastreaza si ”Viflaimul”, un teatru popular in care apar personajele biblice care au legatura cu momentul Nasterii Domnului. Sunt putine localitatile Maramuresului in care mai este prezentat spectacolul, si datorita numarului mare de personaje, peste 20, dar si a pregatirilor minutioase care trebuie facute cu mult timp inainte. In Ieud, dar si in alte localitati de pe Valea Izei traditia s-a mai pastrat, chiar daca ”Viflaimul” nu este prezentat chiar in Ajunul de Craciun. ”Jocul mosilor”, o arta a deghizarii Delia Suiogan a aratat ca ”in cadrul sarbatorilor de iarna, un rol important l-a jucat si il mai joaca inca deghizarea si travestirea, practicate in jocul cu masti. Cei ce se mascau, individual sau in grup, urmareau ca, pe langa proectia reala sau magica sa obtina, cu ajutorul mastilor si legatura spirituala cu presupusele forte supraomenesti”. Ea a aratat ca ”purtatorul mastii este patruns de forta ei, este scos din timpul si spatiul profan”, iar ”masca isi pastreaza functia de pacalire, cu intentia de a asigura celui care o poarta o trecere mai usoara peste «pragurile» pe care le are de depasit, pentru ca masca presupune si o serie intreaga de interdictii, dar ii si da dreptul la un comportament ce iese din tiparele cotidianului, realului imediat”. Ea a mai adaugat ca, in Maramures, un loc important il ocupa mai ales in anii nostri jocul mosilor, la originea caruia se pare ca au stat ceremoniile cu masti din noptile de priveghi - ritual stramosesc de cinstirea mortilor. ”Masca propriu-zisa de mos maramuresan executata din blana de cornute, desi aminteste de animalul originar se deosebeste de masca similara din restul zonelor etnografice ale tarii prin faptul ca nu au coarne”, a spus Delia Suiogan. Potrivit acesteia, jocul mosilor este un moment aparte si se remarca prin ingeniozitatea celor care se deghizeaza si bat la usile gazdelor sa le sperie si sa le ureze fericire si sanatate. Colacutul dat colindatorilor, un simbol al soarelui. Etnologul a mai spus ca un loc important il au si obiectele legate de colindat, amintind de bata, care este vazuta ca un ”arbore al vietii”. Atingerea portilor si a femeilor, dar si bataia repetata atat in podeaua casei, cat si in pamantul din curte cu bata are rol fertilizator, potrivit credintelor din Maramures. De asemenea, un alt obiect ritualic, care nu lipseste din gospodariile maramuresenilor de Craciun, este colacul, care este un simbol al soarelui, dospirea aluatului din care se face semnificand fertilitatea. Mai sunt insa marul - aliment sacru si “fruct al cunoasterii”, si nuca, care este asimilata si “oului cosmic”. Toate aceste se regasesc pe mesele de Craciun in toate gospodariile din Maramures, chiar daca modernismul si-a facut loc chiar si in zonele rurale. ”Toate simbolurile folosite de catre actantii ritualurilor, fie de natura gestuala, obiectuala, fie de natura animala sau vegetala etc. au rolul de a reconstitui mitul (cel al Creatieioriginare sau cel Crestin). Nimic nu este accidental, totul se supune ordinii instituite de memoria mitica. Sarbatoarea Craciunului sau cea a Anului Nou, si nu numai, devin o forma de participare directa la acea ordine cosmica”, a spus Delia Suiogan. Ea a recunoscut ca obiceiurile au fost remodelate” periodic de membrii comunitatii. Superstitiile de Craciun au locul lor in zilele de sarbatoare Prin urmare, sunt extrem de rare situatiile in care podelele casei sunt acoperite cu fan proaspat, iar sub fata de masa sunt puse paie pentru dobandirea bunastarii. De asemenea nu se mai leaga cu lanturi picioarele mesei, obicei care se practica pentru a opri animalele salbatice sa atace vitele din curti si sa indeparteze raul din casa. Superstitiile persista insa, astfel incat nu se da cu matura de Craciun, nu se spala rufe si nu se da nimic cu imprumut. De asemenea, se da de mancare pe saturate animalelor din gospodarie, inclusiv cate o bucatica de aluat dospit, despre care se crede ca le va feri de boli. In unele zone, se spune ca daca in seara de Ajun, animalele se culca pe partea stanga, e semn ca iarna va fi lunga si geroasa. Mai exista si credinta ca acei care plang in Ajun vor plange tot anul care vine, iar in dimineata de Craciun este bine sa te speli pe fata cu apa de izvor in care se pune un banut de argint. Pregatirile de Craciun sunt obligatorii in Maramures, iar tarancile folosesc acest prilej ca sa isi scoata la iveala zestrea lor sau ale fetelor de maritat. Sterguri frumos tesute, perne imbracate in fete brodate cu migala, pleduri colorate sunt scoase din dulapuri si asezate in incaperi, mai ales in cea in care sunt primiti colindatorii. Din case nu lipseste nici bradul, impodobit acum cu beculete si globuri chinezesti, iar altadata cu nuci, mere ori siraguri de boabe de fasole alba in loc de beteala. Masa de Craciun, momentul magic al sarbatorii Cel mai important este ca de Craciun casa sa fie curata si impodobita de sarbatoare, iar masa sa fie plina, pentru ca adunarea membrilor familiei in jurul mesei si al bradului este elementul cel mai bine conservat. Delia Suiogan a aratat ca ”obiceiul apare ca o forma de reconstituire a strangerii tuturor ai casei in jurul buturugii sacre ce se aprindea in vatra casei in Ajun si care are rostul de a-i incarca cu putere pe participanti”. De altfel, chiar exista credinta ca in noaptea de Craciun nu e voie sa se stinga focul in soba, astfel incat barbatul casei obisnuia sa puna pe foc o buturuga mare. Delia Suiogan a spus ca reunirea in jurul mesei de Craciun ete ”revenirea in cerc, ce ar putea fi interpretata ca o forma de initiere ori reinitiere. Pornirea din acest centru «tare» da posibilitatea reconstituirii propriului «centru», astfel incat fiecare casa devine o repetare a «Centrului Lumii», participantii avand prilejul sa se incarce cu putere”. Cat priveste ospatul, acesta se face pentru asigurarea bunastarii, dar este si o forma de sacrificiu: al porcului pentru prepararea carnatilor si caltaboslului, precum si al bobului de grau pentru a face painea. Ritualuri pentru sanatatea si prosperitatea familei Delia Suiogan a mai aratat ca ”foarte multe ritualuri au fost pastrate. Unele nu mai sunt simtite ca obiceiuri, fiind privite ca actiuni obisnuite, dar fac parte din acea serie lunga de gesturi simbolice care ii permit individului ca, periodic, sa aiba sansa unui nou inceput.” Ea a dat ca exemplu taiatul porcului, care este simtit si astazi ca un ritual deosebit de important, gestul amintind de jertfele aduse zeitatilor care se nasteau si mureau periodic, in perioadele de innoire a timpului calendaristic. Sacrificarea acestuia se facea inainte intr-o anumita zi, cea de Ignat si in zorii zilei. Chiar daca data nu se mai respecta, se pastreaza inca o serie intreaga de ritualuri, care au menirea sa asigure sanatatea si prosperitatea in familie in Noul An. Astfel, porcul nu trebuie vaitat si toate activitatile din timpul taierii lui trebuie sa fie insotite de voie buna si de urari. ”In Maramures, se face semnul crucii cu sange pe fruntea coconilor (n.r. – copiilor) ca acestia sa fie sanatosi si puternici. Contactul cu carnea animalului, implicit cu sangele acestuia, inseamna transferul de putere, de viata asupra celui care consuma acest aliment. In acelasi timp, animalul devine mediator intre lumi, intre om si zeu/divinitate, intre om si stramosii sai”, a precizat lectorul universitar. Colinda, o posibila ”cheie” spre portile cunoasterii Craciunul se identifica in Maramures prin colinda, care, in ciuda presiunilor asupra folclorului, nu s-a ”manelizat”, ci s-a pastrat asa cum era cantata de strabuni. Etnologul este de parere ca ”atata vreme cat nu se va apela la mimare si gratuit, Craciunul va ramane acelasi, un timp al bucuriei si al renasterii”, precizand ca i-ar placea ca si peste cinci ani sarbatorea sa fie la fel de frumoasa ca acum, desi se teme ca ”pierderea identitatii ar putea conduce in interiorul procesului de globalizare la fenomenul de dezagregare”. ”Redescoperirea adevaratelor sensuri ale unor gesturi sau obiecte poate sa contribuie la pastrarea traditiei. Astfel, ceremonialul legat de colindatul in comun apeleaza la o serie intreaga de obiecte incarcate de sens si valoare, tocmai datorita functiei lor de mediere intre om si natura, intre om si Cosmos. Ele nu mai sunt simple obiecte, devenind forme de comunicare intre lumi. Colinda mai poate primi si sensul de indicare a directiei, devenind o posibila «cheie» care sa-i deschida Fiintei unele porti spre cunoastere”, a concluzionat etnologul. CRACIUN FERICIT! ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Winter Habits From Romania Romania Engleza ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Winther habits ! Traditional custmes ! ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Summary: Life in the rural environment is simple and complex at the same time: people still follow strict rules of behaviour and maintain ancient traditions, but modern life brings conflicting values even to the remotest villages. A land harmoniously inhabited by various nationalities, Bucovina has withstood the most radical transformations of time and fashion, and has preserved its unforgettable way of life. Small family farms often raise poultry, besides hens, also ducks, geese and turkeys. A typical farmyard in Bucovina generally includes the main house opposite the gate, the summer kitchen to the right, the stable and hay barn to the left, a lower shed between the house and the barn, and a well and a kennel. When several generations live within the same yard, the parents or grandparents move to the summer kitchen, which becomes a secondary dwelling, with only one room and a hall. A typical farmyard in Bucovina generally includes the main house opposite the gate, the summer kitchen to the right, the stable and hay barn to the left, a lower shed between the house and the barn, and a well and a kennel. When several generations live within the same yard, the parents or grandparents move to the summer kitchen, which becomes a secondary dwelling, with only one room and a hall. The walls of this farmhouse are only partly covered with rendering and show the log structure. A peasant of average means had some hectares of land on the outskirts of the village. The land around the farm was exploited for daily living, while the products obtained from the land farther away were sold, or exchanged, to assure the living of the family throughout the year. The structure of the village differs for example from a village in Neamţ, where the houses are lined along the main road, with an orchard behind the house and only a bed of flowers in front of it. In Bucovina each house has its own well in the yard, while in Neamţ a common well is found by the road. A man wearing traditional clothes for the Sunday service. Both his coat and his waistcoat are embroidered. The folk costume is still worn daily by the old, while the younger generations wear uniform western clothes. They rarely wear traditional clothes apart from special occasions. The men’s costume includes white trousers (iţari), which have long legs to fold them several times over, as protection against humidity; a white shirt with mainly geometrical embroidery in black or brown; and a waistcoat (bundiţă) with the white leather turned out and the fur turned in, decorated with floral or geometrical motifs and with marten fur trimmings. Men also wear belts, either woven or made of leather. Sometimes the leather belt is worn on top of the woollen one. The width of the belt depends on the altitude of the village – the higher up the village, the wider the belt. The future bride cut, sewed and embroidered the suit of her husband-to-be during the one-year-long engagement. Women wear a similar waistcoat but the decoration is more colourful. The women’s shirt is richly adorned with floral or geometrical motifs. It is said that the full decoration of the Bucovinean shirts recalls the decoration of the painted churches. Women wear one-piece wrap-around skirts (catrinţe) on top of the knee-length shirt, tied with a wide woven belt. There are specific clothes for the cold seasons, autumn and winter. The suman, used in autumn, is made of a very thick woollen felt cloth. The cojoc, is a knee-length fur coat, with the fur turned inside and the skin outside, decorated with embroidered flowers. Singeing a pig with a gasoline lamp. The flame is strong as the bristles need to be burned quickly. This way the skin is ready for being peeled and eaten The people of Bucovina not only greet strangers, but also offer a place to sleep, not for financial gain but because they are hospitable, and consider it an honour to open the door of their house. And when hungry, the best traditional dishes are served – mămăligă (maize polenta) with fresh cheese and cream, eggs, pork sausages, sarmale (cabbage or vine leaves stuffed with meat and rice), yoghurt, soup or răcituri (jellied meat). Nearly all food is heavy, and digestion is helped with a glass of ţuica (plum brandy). This is the only alcoholic drink commonly used, and is often drunk from the same glass by everybody at the table. Various soups and borş (soup soured with fermented husk of wheat) are eaten every day. A thick mixture of boiled wheat grain, colivă, a patty-like cake for commemorating the dead is still prepared and eaten on special occasions. Oven-baked dishes are usually flour-based cakes and pies. In poale-n brâu -pies, cheese is wrapped in dough, in vărzări, cabbage is used instead as filling (varză=cabbage). Of the traditional Easter baked goods, pască is specific to the countryside and cozonac has its roots in the towns. Pască is made of a rolled out sheet of yeast dough, covered with a mixture of cottage cheese, cream, eggs and sugar, decorated with a figure of a cross made with the dough, and baked in a round tin. Cozonac is made of a sheet of the same dough, covered with nuts, rolled and baked in a high tin. The people of Bucovina are famous sheep and cow breeders, and make very good milk products, which within the region of Moldavia face competition only from those made in the zone of Neamţ. Both Suceava and Neamţ are hilly, with an altitude of 400 m – 1,000 m, with beautiful meadows and good grass. The pastoral year starts in April and ends in October. During this period the sheep stay at the sheepfold, outside the village, under the care of a shepherd. The owners of the sheep receive milk and cheese A young woman carrying periodically, depending on the number of their sheep. The sheep in a horse cart. shepherds are paid in produce rather than money. The same way of bartering was also used at flour mills when grinding grain, or at wine presses when crushing raisins. Nowadays, modern wine presses can be found in almost every house, but flour mills are owned by small companies, and the payment is partly in flour and partly in money. Bucovina is also known for its well-bred domestic birds and pigs, as well as for its excellent potato, cabbage, cauliflower and fruit crops, especially apples, pears, plums and cherries. Cereals are also cultivated, but the crop is mainly meant to cover the requirements of the homestead. Wood processing has always been one of the main occupations in Bucovina. Among the traditional mask plays The Goat is one of the most frequently performed. The life of the Romanian peasant has always been structured around the yearly cycle of labour, agriculture, animal husbandry, hunting, fishing and beekeeping. The life of a peasant has always meant making the land productive, not with the aim of becoming rich, but simply to assure a good living for his family. The yearly cycle is also followed in traditions and beliefs, many related to a good crop and placating the spirits. Among the most important traditional beliefs are the ancestors’ spirits, which are said to return among the living during the winter holidays from Christmas to Epiphany. They do not come with harm in mind and are paid due respect. This belief is mainly visible in the mask playing tradition of this time of the year, with the Old Man and the Old Woman the most usual personages. If these spirits delay the return to their own land there is a risk that they could turn dangerous. In order to chase them away, garlic is put at the windows of the houses. The same mask playing tradition recounts also beliefs in the supernatural powers of animals, such as the bear (symbolizing protection and strength), the goat, the ram, the ostrich, which are represented with realistic masks. ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Winter Habits From Romania Romania-Banat English Romanian ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Feast of the Nativity is celebrated by Christians throughout the world, every country but with their own traditions and customs. Meaning or origin of many of them were lost in the mists of time, but they give an extra beauty mystery winter holidays. One of the most important Romanian Christmas festivities is the carol. In some villages in Timis, centuries-old traditions are still preserved today, so he wandered from house to house, going both children and youth divisions, called "baker". On the first day of Christmas carolers go with "Star" astral recalling that have followed the Three Magi to reach the place where Baby Jesus was born. Another custom is the "Viflaimul" or "Herods", representing a play by recovering children in the house or in the yard of the host, the story of Jesus' birth. Tradition holds that he who receives carol will be blessed and will only luck in the coming year, a sign of wealth and that is the first to enter the house for Christmas is a man. In some villages to store and another custom: the eldest member of the family must throw in the carol singers and corn grains. Elders say that if beans that have passed over carolers will be mixed with the seed that will put the swath will have a very good harvest next year. Also in Banat, there are customary under the table that will celebrate food place to put wires hay and wheat, corn and sunflower, which are then given to cattle, to be quiet house and wealth. Communities of Hungarians and Germans in the Banat, winter religious holidays starting with Advent or "coming (God)", characterized by a waiting time of Jesus happy. On the first Sunday of Advent, Advent for Catholics begins, which lasts four weeks (in the Orthodox tradition, Advent begins on November 15, the run was great celebrating six weeks). Specific symbol of this holiday is the Advent wreath, made of fir branches intertwined with ribbons and decorated with gilded nuts and cones, which are placed four candles that are lit one by one, every Sunday until Christmas Eve. Candles symbolize the light of the Savior Jesus brought on earth, a symbol of hope. To sweeten awaiting Christmas in German communities still customary to make a calendar of Advent - "Adventskalender". The calendar contains one window for each day left until Christmas, behind which children will find one toy, candy or images of the Nativity story. Also on the first day of Advent, in some villages in Banat, breaking a twig from a tree fruit cherry, cherry, plum - and put it in a pot of water to heat. Branch, which will bloom until Christmas, is kept in the house until Epiphany, when the priest is holy, and is attached to a barn wall to protect farm animals. Tudor Ceia: If you think about from the outset that the Banat habits are unique, they are related to practices related to what happens after December 15, until after the end. John the Baptist in January. In practice, linked to the Christmas food that has become a custom made coils and cut pork, December 20 is the day when sf. Ignatius. About food for Christmas is number one seat, comes first and why? Banat coils are primarily for remembrance of the dead, from doing large hoop that they named Christmas and New Year to eat, even here with us, in Giroc, near Timisoara juice of the pig head. Then, all at Giroc, it is customary to make a life for thieves, or come to meet them, give them to eat, they then not attacking you did, or to enjoy your wealth. Then they do the 12 coils for the months of the year, that regarding fertility. Place joined, along with works that are done in the garden, the orchard, the vineyard, in the field during the year. See it here (in carol) are references to house animals besides humans and generations living in the house and of course are those with children, the child who is the symbol of family perpetuation ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Sărbătoarea Naşterii Domnului este celebrată de creştinii din întreaga lume, fiecare ţară având însă propriile datini şi obiceiuri. Semnificaţia sau originea multora dintre ele s-au pierdut în negura vremilor, dar frumuseţea lor dau un plus de mister Sărbătorilor de iarnă.Spaţiu prin excelenţă multicultural, Banatul ne surprinde prin multitudinea de tradiţii şi obiceiuri înrădăcinate în zonă. Excepţie nu face nici Sărbătoarea Crăciunului, de care sunt legate credinţe populare vechi specifice fiecărei etnii ce coabitează aici. Una dintre cele mai importante festivităţi ale Crăciunului românesc o reprezintă colindul. În unele sate din Timiş, tradiţiile vechi de secole se mai păstrează şi astăzi, aşa că la colindat, din casă în casă, merg atât copiii, cât şi cetele de tineri, numiţi “piţărăi”. În prima zi de Crăciun, colindătorii merg cu „Steaua”, amintind de astrul pe care l-au urmat Cei Trei Magi pentru a ajunge la locul unde s-a născut Pruncul Iisus. Un alt obicei este cel al „Viflaimului” sau „Irozii”, reprezentând o scenetă prin care copiii refac, în casa sau în curtea gazdei, povestea naşterii lui Isus. Tradiţia spune că cel care primeşte colindul va fi binecuvântat şi va avea numai noroc în anul care vine, un semn de bunăstare fiind şi dacă prima persoană care intră în casă de Crăciun este un bărbat. În unele sate se păstrează şi un alt obicei: cel mai în vârstă membru al familiei trebuie să arunce în faţa colindătorilor boabe de grâu şi de porumb. Bătrânii spun că, dacă boabele peste care au trecut colindătorii vor fi amestecate cu sămânţa pe care o vor pune în brazdă, vor avea o recoltă foarte bună în anul următor.Tot în Banat, există şi obiceiul ca sub faţa de masă pe care se vor aşeza bucatele sărbătoreşti, să se pună fire de fân şi seminţe de grâu, porumb sau floarea-soarelui, care se dau apoi la vite, ca să aibă casa linişte şi bogăţie. Pentru comunităţile de maghiari şi germani din Banat, sărbătorile religioase de iarnă încep cu Adventul sau „Venirea (Domnului)”, perioadă caracterizată printr-o aşteptare bucuroasă a lui Iisus. În prima duminică de Advent, pentru catolici începe postul Crăciunului, care durează patru săptămâni (în tradiţia ortodoxă, postul Crăciunului începe pe 15 noiembrie, perioada premergătoare marii sărbători fiind de şase săptămâni). Simbolul specific acestei sărbători este cununa de Advent, formată din crenguţe de brad împletite cu panglici şi decorată cu nuci şi conuri poleite, pe care se aşează patru lumânări, care se aprind pe rând, duminică de duminică, până în Noaptea de Ajun. Lumânările simbolizează lumina adusă pe pământ de Iisus Mântuitorul, fiind un simbol al speranţei Pentru a îndulci aşteptarea Crăciunului, în comunităţile de germani se mai obişnuieşte să se facă un calendar de Advent – „Adventskalender”. Calendarul conţine câte o ferestruică pentru fiecare zi care a mai rămas până la Crăciun, în spatele căreia copiii vor găsi câte o jucărie, dulciuri sau imagini din istoria Naşterii.Tot în prima zi a Adventului, în unele sate din Banat, se rupe o crenguţă dintr-un pom fructifer – cireş, vişin, prun – şi se pune într-un vas cu apă, la căldură. Creanga, care va înflori până la Crăciun, e ţinută în casă până la Bobotează, când e sfinţită de preot, apoi e prinsă de un perete din grajd, pentru a proteja animalele din gospodărie.Deosebit de frumoase sunt şi obiceiurile sârbilor legate de sărbătorile de iarnă. Aceştia sărbătoresc Ajunul Crăciunului după calendarul gregorian, pe 6 ianuarie. Una dintre tradiţii este aprinderea Badnjakului – un trunchi de stejar tânăr – în cuptorul casei sau, mai nou, în curtea bisericii. Acest lemn tânăr îl simbolizează pe Mântuitor şi intrarea lui în lume, iar arderea Badnjakului reprezintă căldura iubirii lui Hristos. Se spune că numărul mare al scânteilor provocate de arderea lemnului semnifică şi bogăţia din casa respectivă, pentru anul care vine. Un alt obicei al sârbilor de Crăciun este ca gospodinele să aducă în casă paie, care semnifică ieslea Pruncului Iisus. Primul musafir de Crăciun trebuie să fie bărbat. Asupra acestuia se aruncă grâu, iar el trebuie să adune nucile pe care gazda le aruncă în cameră, prin paie. Tudor Ceia: Dacă vă gîndiţi de la început că obiceiurile din Banat sunt unice, ele sunt legate de practicile legate de ce se întimplă, imediat dupa 15 decembrie, pînă după sf. Ion Botezătorul în ianuarie. În mod practic, legat de alimentele de Craciun care, a devenit un obicei, făcutul colacilor şi tăiatul porcului, la 20 decembrie cînd este ziua sf. Ignat Teoforul. Despre alimentele de Craciun: colacul este pe locul întăi, primează şi de ce ? Bănăţenii fac în primul rînd colaci pentru pomenirea morţilor, pe urma fac colacul mare pe care l-au botezat Craciunul şi care se mănîncă la Anul Nou, chair aici la noi, la Giroc, lîngă Timişoara cu zeamă din capul porcului.Pe urmă, tot la Giroc, se obişnuieşte să se facă un colac pentru hoţi, adică vii în întîmpinarea lor, le dai de mîncare, ca ei după aceea sa nu îţi mai atace avutul, sau să se bucure de avutul tău. Pe urma se mai fac cei 12 colăcei pentru lunile anului, asta vizînd rodnicia. Se pun alăturat, paralel cu lucrarile care se fac în grădină, în livadă, în vie, în cîmp pe parcursul anului.Vedeţi că aici (in colind) se fac referiri şi la animalele de pe lîngă casa omului şi la generaţiile care trăiesc în casă şi bineînţeles că sunt şi cei cu copii, copilul care este simbolul perpetuării familiei. Tudor Ceia: Nu am notată melodia, dar suna foarte frumos. Se combină cu faptul că atunci cînd intră colindătorul în casă neapărat are în mînă o tufă de cu toamna, rupe floarea de noroc şi o creangă de busuioc de stropit casa. Stropiţi masa, stropiţi feţi şi fetce mari, fetce mari s-or pomeni şi frumos ne-or dărui un colac de grîu curat, pe colac vasul cu vin a asa e legea din batrini, din oameni buni... la anul şi la multi ani! ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea Maramureș County. • Maramureș is a county (județ) of Romania, in the Maramureș region. The county seat is Baia Mare. Geography. • This county has a total area of 6,304 square kilometres (2,434 sq mi), of which 43% is covered by the Rodna Mountains, with its tallest peak, Pietrosul, at 2,303 metres (7,556 ft) altitude. Together with Gutâi and Țibleș mountain ranges, the Rodna mountains are part of the Eastern Carpathians. The rest of the county are hills, plateaus, and valleys. The county is crossed by Tisa River and its main tributaries: Iza, Vișeu, and Mara rivers. Demographics. • In 2011, the county had a population of 461,290 and a population density of 73.17 inhabitants per square kilometre (189.5 /sq mi). Romanians - 82.38% (or 380,018)[3] Hungarians - 7.53% (or 34,781) Ukrainians - 6.77% (or 31,234) Roma - 2.73% (or 12,638) Germans - 0.27% (or 1,243), and others. Tourism. • The region is known for its beautiful rural scenery, local small woodwork and craftwork industry as well as for its churches and original rural architecture. There are not many paved roads in rural areas, and most of them are usually accessible. • The county's main tourist attractions: • The cities of Baia Mare and Sighetu Marmației. • The villages on the Iza, Mara, and Vișeu Valleys. • The Wooden Churches of Maramureş • The Wooden Churches of Lăpuş • The Wooden Churches of Chioar • The Merry Cemetery of Săpânța • The Rodna Mountains. • The landscape of Cavnic. History. • The 10th century frontier county of Borsova was founded by Stephen I of Hungary. Since then Máramaros served as the north-eastern border of the Hungarian Kingdom until 1920, the Trianon Peace Treaty. • 11th century historical Maramureș counties separation from Borsova (Rom. Borşa) • 1241 Tartar invasion decimated about half of the local population • 14th century Duke (knyaz) Bogdan of Maramureș said to be founder of Moldova • In the Middle Ages, the historical region of Maramureș was known for its salt mines and later for its lumber In 1920 after the Treaty of Trianon, the northern part of the county became part of newly formed Czechoslovakia. The southern part (including Sighetu Marmației) became part of Romania. ROMANIA LITUANIA Comenius Multilateral Project “The language of art” Romanian workshop and final product – “Winter habits” LETONIA Coordinator of the project: prof. Gabriela Ivan TURCIA POLONIA Workshop conducted by prof. Mihaela Codrea