Chapter Four

The General Principles of

Criminal Liability:

Mens Rea, Concurrence,

Causation and Ignorance and

Mistake

Chapter Four Learning Objectives

• Understand and appreciate that most serious

crimes require criminal intent and a criminal

act.

• Understand the difference between general

and specific intent.

• Understand and appreciate the differences in

culpability among the Model Penal Codes’

four mental states—purposefully, knowingly,

recklessly and negligently.

Chapter Four Learning Objectives

• Understand that criminal liability is sometimes

imposed without fault under strict liability.

• Understand that the element of causation

applies only to “bad result” crimes.

• Understand that ignorance of facts and law

can create a reasonable doubt that the

prosecution has proved the element of

criminal intent.

Elements of Crime

• Voluntary act (prior chapter)

• Mens rea—criminal intent

– Most serious crimes require a mental element called mens rea

(criminal intent)

– Required because of culpability or blameworthiness

– Most states and the Federal government follow common law

principles about mens rea

– Mens rea is not one level of intent, it comprises a range of intent—

generally broken down by the degree of blameworthiness

• Concurrence—requirement that criminal intent trigger the criminal act in

conduct crimes; criminal conduct must cause bad result in bad result

crimes

• Causation

– Criminal act must be both the cause in fact and the legal cause of the

criminal harm

Criminal Intent—Mens Rea

• Ancient requirement

• Complex

– Difficult to prove in court

– Difficult to grasp and define in legislation

• Several mental attitudes that range across the

spectrum

• Different mental attitudes may apply to

different elements of the crime

Mens Rea (continued)

• Mens rea is different than motive

– Example: Man kills wife for money

• Mens rea = intent to kill

• Motive = get money

• Motive is “irrelevant” to criminal liability

– Meaning, state doesn’t have to prove a specific motive to prove the

case…but known motives help establish a case….and are “relevant” in

the evidentiary sense (the state will be able to introduce them as

evidence in trial)

• Motive may be important in establishing a defense

• Motive may be an element of crime—attendant circumstance

– Example: burglary - “for the purpose of committing a crime”

Proving Mens Rea

• Confessions are the only direct evidence of

mental attitude

• Proof of intent usually rests on indirect,

circumstantial evidence

• It is common in everyday life to infer people’s

intent from what they do

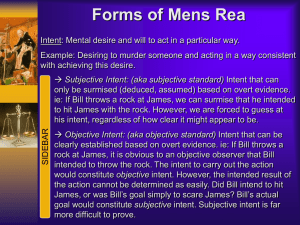

Fault

• Subjective fault—fault that requires a bad mind

– Ex. Receiving an iPod you know is stolen

– Bad state of mind is “knowingly”

– Terms also used to express subjective fault

• Ill will, depravity of will, depraved heart

• Objective Fault—fault that requires no bad mind

in the actor

– Ex. Buying an iPod for $10.00 thinking it is new

– Average person would have known that it was

stolen—even if you didn’t

Strict Liability

• Criminal liability that does not require either

subjective or objective fault

– Example: a statute that states “whoever receives

stolen property…”

• There is no requirement that person knowingly receive

stolen property

General and Specific Intent

• General intent: the intent to commit the criminal act defined

in the statute

– Courts don’t always define general intent the same way

– The minimum requirement of all crimes

• Specific intent: intent to cause the result (in bad result

crimes)

– Generally has subjective fault component “bad mind”

– Adjectives used include Deliberate, conscious, intended, planned,

premeditated…etc.

• General intent “plus”: intent to commit the criminal act plus

some mental element

– most common definition of specific intent

– Example: Burglary is specific intent. Burglar has to intend to break and

enter and has to intend to commit some crime while inside

Harris v. State (1999)

• Harris carjacked his friend’s vehicle after a night of

drinking when his friend refused to drive him to DC.

• Harris raised voluntary intoxication as a defense,

claiming that he could not form the requisite intent,

and appealed his conviction.

• The appeals court held that the crime of carjacking is

a general intent crime to take control of a vehicle

from another individual, and there need not be

another remote purpose or intent (i.e. To

permanently deprive the owner of the vehicle)

Summary of Case Holding

• Court held that the mens rea requirement for

carjacking in Maryland was the general intent

to obtain unauthorized possession or control

of car from person in action possession by

force…

• Court looked at legislative history and decided

that the legislature only intended to establish

general intent (not a specific intent crime)

Model Penal Code Mental States

•

•

•

•

Purposefully

Knowingly

Recklessly

Negligently

• Product of debate

• Ranked according to degree of culpability

from highest to lowest

Purposefully

• Actors conscious object is to engage in

conduct or cause a result

Knowingly

• (conduct crime) actor is aware that his

conduct is of a certain nature or that a

circumstance exists

• (bad result crime) actor is aware that it is

practically certain that his conduct will cause

such a result

Recklessly

• Actor consciously disregards a substantial and

unjustifiable risk that the material element

exists or will result from his conduct

Negligently

• Actor should be aware of a substantial and

unjustifiable risk that the material element

exists or will result from his conduct

• Risk must be a nature and degree that actor’s

failure to be aware of the risk….involves a

gross deviation from the standard of care

observed by a reasonable person in the actor’s

circumstance

“Purposely”

• Most blameworthy mental state

• To do something on purpose

• Having conscious object to commit the crime,

cause the result

State v. Stark (1992)

• After testing HIV Positive, and being extensively

counseled as to “safe sex” and the necessity of

informing partners of his status, Stark repeatedly

engaged in unprotected sex with uninformed

partners, and was quoted at trial as saying “I don’t

care. If I’m going to die, everybody is going to die”

• Stark was convicted of Assault in the 2nd Degree

(Intent to inflict bodily harm) and appealed, claiming

he did not “intend” to expose anyone to HIV

• The court affirmed the conviction.

Summary of case holding

• Sufficient evidence from defendant’s actions

that he purposefully intended to exposing his

partners with AIDS

– Counseling Sessions (Knowledge of Risk, Protocols

and the Law)

– Stark’s statement when confronted about his

sexual behavior (Knowledge of bad result)

– Sexual behaviors attempted with one victim that

were specific practices to avoid .

Knowing

• Conduct Crimes = awareness of what you are

doing

• Bad result crimes = practically certain that

conduct will cause the bad result (don’t need

to have a conscious objective

Case: State v. Jantzi (1982)

• Jantzi was convicted of Assault in the 2nd Degree

when he possessed a dangerous weapon (Knife), and

knew that a confrontation was going to occur.

• At the point the confrontation began, Jantzi had fled,

and concealed himself in a bush, when his victim

jumped on him and was stabbed. Jantzi appealed as

he claimed that he did not intend to assault his

victim.

• The court agreed, and reduced the conviction to

Assault 3rd (lesser included offense), based upon the

level of intent (Acted Recklessly not Knowingly).

Summary of case holding

• Trial court erred in finding that defendant acted

knowingly… the Trial judge described reckless

behavior, so appellate court reversed and entered

judgment on lesser charge

• Case highlights the difficulty in grasping the

mental state

• Knowing that it is possible that injury will occur is

not knowing….it is reckless.

• Knowing means actor has to be practically certain

the harm will result

Reckless

• Awareness of the risk of causing criminal

harm, then do the act anyway (Consciously

Creates the risk)

• Recklessness doesn’t apply to conduct crimes

– Have to be aware that you are committing a

voluntary act

– Recklessness is to the result

• A reckless person creates a risk of harm, but

doesn’t intend, or expect to cause the harm

Reckless

Model Penal Code

2 Prong Test:

1. Risk has to be substantial and unjustifiable

2. Disregarding the risk has to be a gross

deviation from the standard of care a

reasonable person would exercise under

the circumstances

Negligent

• Unconsciously creating a risk of harm

• Should have been aware of the risk

• Failure to be aware of the risk is a gross

deviation of the standard of care a reasonable

person would have under the circumstances

– A reasonable person would have realized they

were creating the risk

• Risk has to be substantial

• Risk has to be unjustifiable

Koppersmith v. State (1999)

• Koppersmith was charged with the Murder of his

wife in a domestic altercation, and was subsequently

convicted of Reckless Manslaughter. Koppersmith

had requested a jury instruction on negligent

homicide, which was denied, and formed the basis of

his appeal.

• Koppersmith claimed that when he physically “slung”

his wife to the ground and moved here head up and

down on the ground (as if slamming it into the

ground), he was unaware that there were bricks in

the grass.

• The appeals court agreed.

Summary of case holding

• “The reckless offender is aware of the risk and

“consciously disregards” it…vs…

• On the other hand, the criminally negligent offender is

not aware of the risk created (“fails to perceive”) and,

therefore, cannot be guilty of consciously disregarding

it.

• The difference between the terms “recklessly” and

“negligently” is one of kind, rather than degree. Each

actor creates a risk of harm. The reckless actor is

aware of the risk and disregards it; the negligent actor

is not aware of the risk but should have been aware of

it”.

• Court held that there was evidence that defendant

could have failed to perceive the risk, so the jury

instruction on negligence should have been given.

Strict Liability

• Liability without fault—based on the voluntary

act alone

• U.S. Supreme Court has upheld power of

legislatures to make strict liability crimes

– To protect public health and safety

– Make clear they are imposing liability without

fault

Strict liability (continued)

• Support:

– Strong public interest in protecting public health

and safety. These laws arose out of industrial

revolution and aimed at protecting workers and

citizens from ills of manufacturing, mining,

commerce, etc.

– Penalty is usually (but not always) mild

Strict liability (continued)

• Criticism:

– Too easy to expand strict liability beyond offenses

that endanger the public

– It “does no good” to punish people who don’t act

purposefully, knowingly, recklessly, or negligently

– Criminal law without blameworthiness loses its

appeal as a moral code

State v. Loge (2000)

• Loge was stopped for speeding in his fathers pick-up

when officers noticed an open container of beer.

Although Loge admitted drinking 2 beers earlier in

the evening, he denied the open container was his.

After passing a field sobriety check, he was issued a

citation for the open container under the state’s

Strict Liability Open Bottle Statute, and was

subsequently convicted.

• Loge appealed, based on the lack of a requirement

for a proof of knowledge.

• The court disagreed, and upheld the statute.

Summary of case holding

• The court looked at legislative history of the open

bottle statute, examined other similar statutes

with similar language and concluded that the

Minnesota Legislature intended to create the

strict liability crime. Note the careful attention

the court paid to the specific language of the

statute.

• “It is therefore reasonable to conclude that the

legislature, weighing the significant danger to the

public, decided that proof of knowledge….was

not required.”

Concurrence

• Some mental fault has to trigger the conduct

(conduct crimes)

• Some mental fault has to trigger the conduct

and the cause (in bad result crimes)

• Rarely an issue in cases

Causation

• Holding an actor accountable for the results of

conduct

• Applies only to bad result crimes

• Distinguish between two types of causation—

both are necessary in order to prove criminal

liability

– Factual cause (aka “but for” causation, actual

causation, “except for” causation

– Legal cause (aka proximate cause)

Factual Cause

• Did the actor set into motion a chain of events

that ended in the result? If so, they are a

factual cause of the result.

• But for the actors conduct, the result would

not have occurred

– Example: Rolling a giant Rock Downhill toward a

crowd

• According to the Model Penal Code:

– “Conduct is the cause of a result when it is an

antecedent but for which the result in question

would not have occurred”

Factual Cause

• Necessary to prove that actor was factual

cause of the harm in order to show criminal

liability. BUT, it is not sufficient to prove

criminal liability.

• Taken to logical extreme, almost anything can

be the factual cause of something if you go

back far enough….E.g., “had his mother not

given birth, the defendant would not have

been in the place to hit the victim”

Legal Cause or Proximate Cause

• Necessary to prove that defendant is legal cause of harm in

order to show criminal liability

• Legal cause asks whether it is fair to hold defendant

responsible for the harm

• Factors in the fairness determination include:

– Whether the result was foreseeable from the conduct

– Whether some other factor contributed to the harm

(Intervening harm)

– Whether the intervening factor was a natural occurrence?

(Natural occurrences don’t generally break off liability)

When an intervening cause cuts off liability (because it is

more fair to attribute the harm to it) it is said to be a

superseding cause

People v. Armitage (1987)

• While intoxicated, Armitage took an intoxicated

friend aboard his boat on the Sacramento river at

3am, where his reckless operation resulted in the

boat capsizing, and his passenger drowning.

• Armitage was convicted of Intoxicated Boating

resulting in Death, and Appealed, claiming that the

death was not the proximate result of his actions;

rather, the intervening or superseding cause being

his passenger’s panic response to swim to shore.

• The court disagreed

Summary of case holding

• Court concluded that the victim’s attempt to swim ashore

after defendant’s reckless boating resulted in a capsized

boat was a natural and continuous sequence arising from

defendant’s acts. Contributory negligence of the victim is

not a defense.

• “In order to exonerate a defendant the victim’s conduct

must not only be a cause of his injury, it must be a

superseding cause. A defendant may be criminally liable

for a result directly caused by his act even if there is

another contributing cause. If an intervening cause is a

normal and reasonably foreseeable result of the

defendant’s original act, the intervening act is dependent

and not a superseding cause and will not relieve

defendant of liability.”

Velazquez v. State (1990)

• Velazquez and Alvarez mutually agreed to a

drag race which ended in a crash.

• Neither vehicle struck the other, although

both crashed nearby one another, and Alvarez

was killed.

• Velazquez was charged with vehicular

homicide, and appealed on the basis he was

not the proximate cause of Alvarez Death.

• The appeals court agreed

Summary of case holding

• The court held that the defendant was not the

proximate cause of victim’s death. The judge

found that policy considerations were against

imposing responsibility for the death of a

participant in a race on the surviving racer

when the sole contribution to the death was

participation in the mutually agreed on

activity.

People v. Kibbe (1974)

• Kibbe and a companion assaulted and robbed a

highly intoxicated individual who was ejected from a

vehicle on a dark road, late at night, stripped of his

clothing and eyeglasses, where he was struck and

killed by another vehicle.

• Kibbe was convicted of the Homicide, and appealed,

claiming his actions were not the proximate cause of

the man’s death, the intervening act of the other

vehicle was the superseding cause of the death.

• The appeals court disagreed.

Summary of holding

• Court held that Kibbe and his co-defendant

were the proximate cause of victim’s death.

• The death could have been foreseen as being

reasonably related to the acts of the accused.

• Although another truck actually hit the victim,

the court found that it was not an intervening

wrongful act which would relieve the

defendants from the foreseeable

consequences of their actions.

Ignorance and Mistake

• Mistake is a defense when it negates the mens rea

• Characterized as either

– A defense of excuse

– A failure of proof defense(can’t prove the requisite mental

state)

According to the Model Penal Code, mistake matters

when it prevents the formation of a mental attitude

required by a criminal statute (refer to statute)

Mistake cannot negate criminal liability for strict liability

crimes (because they do not require mens rea)

State v. Sexton (1999)

• Sexton was convicted of reckless

manslaughter after he fired a gun he

mistakenly believed was unloaded, and killed

his friend.

• Sexton appealed on the basis of failure of

proof by the prosecution, on the basis of

instruction to the jury on the elements of the

crime, and the culpable mental state.

• The court affirmed the appeal.

Summary of case holding

• This case highlights the approach used by the

MPC viewing mistake as a failure of proof

when it negates a required element of the

offense (Claim of Mistake = Negligence and

would have mitigated the culpable mental

state of Recklessness)

• “To sum up, evidence of an actor’s mistaken

belief relates to whether the State has failed

to prove an essential element of the charged

offense beyond a reasonable doubt.”