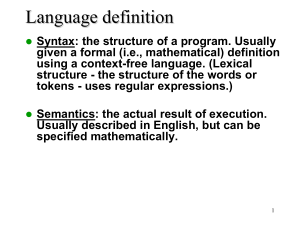

1. Objective-C Basic Programming Concepts

advertisement

Introduction to

Objective-C Programming

(Level: Beginner)

Lecture 1

1

Introduction

• Objective-C is implemented as set of extensions

to the C language.

• It's designed to give C a full capability for objectoriented programming, and to do so in a simple

and straightforward way.

• Its additions to C are few and are mostly based

on Smalltalk, one of the first object-oriented

programming languages.

2

Why Objective C

• Objective-C incorporates C, you get all the benefits of C

when working within Objective-C.

• You can choose when to do something in an objectoriented way (define a new class, for example) and when

to stick to procedural programming techniques (define a

struct and some functions instead of a class).

• Objective-C is a simple language. Its syntax is small,

unambiguous, and easy to learn

• Objective-C is the most dynamic of the object-oriented

languages based on C. Most decisions are made at run

time.

3

Object-Oriented Programming

• The insight of object-oriented programming is to

combine state and behavior, data and

operations on data, in a high-level unit, an

object, and to give it language support.

• An object is a group of related functions and a

data structure that serves those functions. The

functions are known as the object's methods,

and the fields of its data structure are its

instance variables.

4

The Objective-C Language

• The Objective-C language is fully

compatible with ANSI standard C

• Objective-C can also be used as an

extension to C++.

• Although C++ itself is a Object-Oriented

Language, there are difference in the

dynamic binding from Objective-C

5

Objective-C Language (cont.)

• Objective-C source files have a “.m”

extension

• “.h” file is the interface file

• For example:

– main.m

– List.h (Interface of List class.)

– List.m (Implementation of List class.)

6

ID

• “id” is a data type used by Objective-C to

define a pointer of an object (a pointer to

the object’s data) (sort of like * in C++)

• Any type of object, as long as it is an

object, we can use the id data type.

• For example, we can define an object by:

id anObject;

• nil is the reserved word for null object

7

Dynamic Typing

• “id” data type has no information about the

object

• Every object carries with it an isa instance

variable that identifies the object's class,

that is, what kind of object it is.

• Objects are thus dynamically typed at run

time. Whenever it needs to, the run-time

system can find the exact class that an

object belongs to, just by asking the object

8

Messages

• To get an object to do something, you

send it a message telling it to apply a

method. In Objective-C, message

expressions are enclosed in square

brackets

[receiver message]

• The receiver is an object. The message is

simply the name of a method and any

arguments that are passed to it

9

Messages (cont.)

• For example, this message tells the myRect

object to perform its display method, which

causes the rectangle to display itself

[myRect display];

C++ equiv: myRect.display();

[myRect setOrigin:30.0 :50.0];

C++ equiv: myRect.setOrigin(30.0, 50.0);

• The method setOrigin::, has two colons, one for

each of its arguments. The arguments are inserted

after the colons, breaking the name apart

10

Polymorphism

• Each object has define its own method but for

different class, they can have the same method

name which has totally different meaning

• The two different object can respond differently

to the same message

• Together with dynamic binding, it permits you to

write code that might apply to any number of

different kinds of objects, without having to

choose at the time you write the code what kinds

of objects they might be

11

Inheritance

• Root class is NSObject

• Inheritance is

cumulative. A Square

object has the methods

and instance variables

defined for Rectangle,

Shape, Graphic, and

NSObject, as well as

those defined

specifically for Square

12

Inheritance (cont.)

• Instance Variables: The new object contains not

only the instance variables that were defined for its

class, but also the instance variables defined for

its super class, all the way back to the root class

• Methods: An object has access not only to the

methods that were defined for its class, but also to

methods defined for its super class

• Method Overriding: Implement a new method with

the same name as one defined in a class farther

up the hierarchy. The new method overrides the

original; instances of the new class will perform it

rather than the original

13

Class Objects

• Compiler creates one class object to

contain the information for the name of

class and super class

• To start an object in a class:

id myRectx; myRect = [[Rectangle alloc] init];

• The alloc method returns a new instance

and that instance performs an init method

to set its initial state.

14

Defining a Class

• In Objective-C, classes are defined in two

parts:

– An interface (.h) that declares the methods

and instance variables of the class and

names its super class

– An implementation (.m) that actually defines

the class (contains the code that implements

its methods)

15

The Interface

• The declaration of a class interface begins

with the compiler directive @interface and

ends with the directive @end

@interface ClassName : ItsSuperclass

{

instance variable declarations

}

method declarations

@end

16

Declaration

Instance Variables:

float width;

float height;

BOOL filled;

NSColor *fillColor;

Methods:

• names of methods that can be used by class objects,

class methods, are preceded by a plus sign

+ alloc

• methods that instances of a class can use, instance

methods, are marked with a minus sign:

- (void) display;

17

Declaration (cont.)

• Importing the Interface: The interface is

usually included with the #import directive

#import "Rectangle.h"

• To reflect the fact that a class definition builds on

the definitions of inherited classes, an interface

file begins by importing the interface for its super

class

• Referring to Other Classes: If the interface

mentions classes not in this hierarchy, it must

declare them with the @class directive:

@class Rectangle, Circle;

18

GCC and Objective-C

• Objective-C is layered on top of the C language

• iPhone & iPad “native” applications are written in

Objective C

• The Apple dev kit for Objective-C is called

“Cocoa”

• Can be written on any computer that has GCC

plus “GNUstep” plug-in

• Apple computers have all of this pre-installed,

and also have an iPhone simulator in the XCode

IDE

19

Tools

• Apple: pre-installed with the Cocoa frameworks

– XCode or GCC in terminal window

• Ubuntu: GnuStep is a free clone of Cocoa

– sudo aptget

– install buildessentials

– gobjc gnustep

– gnustepmake

– gnustepcommon

– libgnustepbasedev

• Windows: http://www.gnustep.org/

20

File Overview

• Source code files have a .m extension

• Header files have a .h extension

• You can use gcc to compile in the same

way as C code

• But, you will need to add the Cocoa or

GNUStep frameworks to the build.

21

Uses ARC – Compile with Xcode

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

int main(int argc, const char * argv[])

{

@autoreleasepool {

// insert code here...

NSLog(@"Hello, World!"); }

return 0;

}

NSLog() is equivalent to a C printf()

Very similar to C, C programs are valid in Objective-C

22

No ARC – Compile with GCC

23

Compiling Hello World in Xcode

(Mac)

• File->New Project

– Mac OS X category – Select Application

– Command Line Tool

– Type - “Foundation”

• Name project helloworld and choose folder

• Save.

• Note that Foundation.framework has been included

for us already

• “Build and run”.

• The debugger console should show “Hello World”

24

Compiling Hello World on Terminal

(Mac)

• Write hello.m using a plain text editor. Compile:

gcc –framework Foundation hello.m –o hello

or use: “clang”

• Foundation brings in the Foundation framework

(Cocoa) which bundles together a set of

dependencies (header files and libraries). You

will need this every time we compile Objective C

code.

• Type: ./hello will run the program in the terminal

• Note: this approach is fine for early examples

but the iPhone applications will be much easier

25

to build in XCode.

Intro to HelloWorld

• Objective-C uses a string class similar to the

std::string or Java string. It is called

NSString.

• Constant NSStrings are preceded by @ for

example: @”Hello World”

• You will notice that NSLog() also outputs

time and date and various extra information.

NSAutoreleasePool* pool

=[[NSAutoreleasePool alloc] init]; allocates a

lump of memory

• Memory must be freed with [pool drain];

26

Example 2

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

int main(int argc, const char* argv[]) {

NSAutoreleasePool* pool = [[NSAutoreleasePool alloc] init];

NSLog (@”Hello World”);

int undergrads = 120;

int postgrads = 50;

int students = undergrads + postgrads;

NSLog (@”Now featuring...\n %i iOS students”, students);

[pool drain];

return 0;

}

27

Some things to note

• No line break needed at end of NSLog

statements.

• NSString constants use C-style variables.

• Test this program to see results.

28

@interface

@interface ClassName : ParentClassName

{

declare member variable here;

declare another member variable here;

}

declare method functions here;

@end

•

•

•

•

Equivalent to C class declaration

Goes in header (.h) file

Functions outside curly braces

Don’t forget the @end tag

29

@implementation

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

#include “Example.h“

@implementation ClassName

define method function here;

define another method function here;

define yet another method function here;

@end

● Equivalent to C class function definitions

● Goes in source (.m) file

● Don't forget the @end tag

30

Example 3: Student.h

@interface Student : NSObject

{

int mUndergrads;

int mPostgrads;

}

-(void) print;

-(void) setUndergrads: (int) undergrads;

-(void) setPostgrads: (int) postgrads;

@end

31

Some things to note

• NSObject is the “root” object in Objective-C

• No direct access to instance variables so we write

some get/set “instance methods”

• “Instance methods” (affect internal state of class)

are preceded with a minus sign

• “Class methods” (higher level functions) are

preceded with a plus sign e.g. create new class

• Method return type in parentheses

• Semicolon before list of parameters

• Parameter type in parenthesis, followed by name

32

Example 3: Student.m

#include “Student.h”

@implementation Example

-(void) print {

int totalStudents = mUndergrads + mPostgrads;

NSLog (@”Total students in CompSci = %i”, totalStudents);

}

-(void) setUndergrads: (int) undergrads {

mUndergrads = undergrads;

}

-(void) setPostgrads: (int) postgrads {

mPostgrads = postgrads;

}

@end

33

Some things to note

• Note prefix minus sign

• Very similar to C

• Same format as with the interface

34

Example 3: main.m

#import <Foundation/Foundation.h>

#include “Student.h”

int main(int argc, char* argv[]) {

NSAutoreleasePool* pool = [[NSAutoreleasePool alloc] init];

id myStudent; myStudent = [[Student alloc] init]; //

allocate and initialize all in one!

Student* iOSstudent; // pointer

iOSstudent = [Student alloc];

// allocate memory

iOSstudent = [iOSstudent init]; // initialize

[iOSstudent setUndergrads: 120]; // apply method to instance

[iOSstudent setPostgrads: 2000];

[iOSstudent print];

[myStudent print];

[iOSstudent release];

[myStudent release];

[pool drain];

return 0;

35

}

Some things to note

• Applying methods to instance format:

[receiver message];

• Semi-colon for variables or values passed

to methods

• [pool drain] etc. are also applying methods.

• Built-in messages; alloc, init, release.

36

Some other things to note

alloc is equivalent to C++ new but it also zeros

all variables

init should be applied to an instance before use

These are often combined in shorthand:

Student* iOSstudent = [[Student alloc] init];

There is no garbage collection on iOS, so we

should release all of our instance memory.

37

To compile example 3

• Create a project in Xcode

(don’t use “Auto Reference Counting” if

you cut-n-paste from this lecture)

• Use ARC with the example code provided

separately.

• Note: You will probably use “ARC” for all of

your other projects

• Compile and run!

38

Data Structures

• Objective-C arrays are similar to C arrays, but

you can initialize whole array in a list.

• Or just a few indices of the array. The rest are

set to 0. Or mix and match:

int values[3] = { 3, 4, 2 };

char letters[3] = { 'a', 'c', 'x' };

float grades[100] = {10.0,11.2,1.1};

int array[] = {[3]=11,[2]=1,[7]=0};

39

Multi-dimensional Arrays

• Can be initialized by using subset notation with

braces. Note no comma after second subset.

• Subset braces are optional, the compiler will fill in

blanks where it can as with 1D arrays.

int array[2][3] = {

{ 0, 3, 4},

{ 1, 1, 1}

};

int array[2][3] = {0, 3, 4, 1, 1, 1};

40

Arrays and Functions

• Arrays can be passed as arguments to functions.

• This function will print every integer in an array but it needs

to also be told how long the array is (arrayLength).

• Statements with hard-coded indices such as array[4] are

potentially dangerous.

void function(int array[], int arrayLength) {

int fourthValue = array[4];

for (int i = 0; i < arrayLength; i++) {

NSLog(@”%i”, array[i]; }

}

41

Structs

• Similarly, the Objective C “struct” can be

initialized in one go.

• Use the '.' member notation or just use

values in the correct order or use some

values. 'unknown.'

• In the following example we explicitly

define the last member but the others are

undefined.

42

Structs

struct Student {

int BSYears;

int PhDYears;

int WellSpentYears;

};

Student myCareer = {

.BSYears = 3, .PhDYears = 3, .WellSpentYears = 6

};

Student poorLifeDecisions = { 3, 8, 3 };

Student unknown = { 3 };

Student andFurtherMore = { .WellSpentYears = 0 };

43

Fitting into limited memory: Unions

• Union data structures allow ambiguity.

• Useful for allowing one storage area to hold different

variable types.

• Can only hold one of the variables at a time.

• Must be careful to ensure retrieval type matches last type

stored.

• Might come in handy for storing lists of “data” that might be

of different types.

• The next example gives ones potentially practical use;

• A series of recordings store ‘Data.’

• The struct has a char to indicate the type of data recorded

in Data.

44

Memory Management

Memory management in Objective-C is semiautomatic:

The programmer must allocate memory for

objects either

a) explicitly (alloc) or

b) indirectly using a constructor

No need to deallocate

45

Allocation

• Allocation happens through the class method alloc.

• The message ‘alloc’ is sent to the class of the

requested object. Alloc is inherited from NSObject.

Every alloc creates a new instance (=object)

[HelloWorld alloc];

• The class creates the object with all zeros in it and

returns a pointer to it.

HelloWorld *p = [HelloWorld alloc];

• The pointer p now points to the new instance. Now

we send messages to the instance through p.

46

The reference counter

• Every instance has a so called reference

counter. It counts how many references are

retaining the object. The counter is 1 after

allocation. It does not count how many

references exist to the object

• Sending the retain message to the object

increases the reference counter by 1.

• Sending the release message decreases the

reference counter by 1.

47

reference counter = retain counter

• When the reference counter reaches zero,

the object is automatically de-allocated.

The programmer does not deallocate.

• The programmer only does:

alloc

retain

release

48

Rules for memory management

• The method that does an alloc or a retain

must also do a release, it must maintain

the balance between:

(alloc or retain) and (release)

• If a method does alloc and returns a

pointer to the created object then the

method must do an autorelease instead

of release. The calling code can do

(retain – release) but this is not a must.

49

Autorelease pool – if no ARC

• For autorelease to work the programmer

must create an autorelease pool, using:

NSAutoreleasePool *pool

= [[NSAutoreleasePool alloc] init];

• When Cocoa is used then the autorelease

pool is created automatically, the

programmer does not need to do it.

• To release the pool and all objects in it, do:

[pool release];

50

Constructors

• This is a class method that allocates and

initializes an object. The programmer is

neither doing alloc nor init.

• Example:

+(id)studentWithName :(NSString*)name AndGpa:(float)gpa

{ id newInst = [[self alloc]initStudent:name :gpa];

return [newInst autorelease];

}

51

Constructors

• Essential: the method sends alloc to ‘self’

which is the Student class object

• Essential: the method autoreleases the

instance, because it returns a pointer to

the created instance

• Not essential: This example uses an

existing initializer, it could use something

else or initialize the Student data directly

52

Constructors

Calling the constructor:

id stud

= [Student studentWithName:@"Johnnie" AndGpa: 3.8];

The message is sent to the Student class

object and returns a pointer to it, the

pointer is assigned to stud

The calling code does neither alloc nor init

An autorelease pool must be in place

53

Something to note!

• You can program for either iOS or OSX or

both in the latest XCode.

• If you are going to do the examples for

both simultaneously be aware that there

are two sets of .h and .m files (one for

each).

54

Frameworks

UIKit framework for developing standard iOS GUIs (buttons

etc.)

UITextField (user-entered text that brings up the keyboard)

UIFont

UIView

UITableView

UIImageView

UIImage

UIButton (a click-able button)

UILabel (a string of text on-screen)

UIWindow (main Window on iPhone)

55

iOS programming

• Event driven framework

• Interface Designer has some extra macros for

the code that act like hooks to variables;

– IBAction - trigger events like mouse clicks

– IBOutlet - captures outputs from events

• These tags are not compiled (don't affect the

code) but sit as an extra before variables that

the Interface Designer can see.

56

End of Lecture 1

• Next, we will be doing more Object-C

programming and building more

applications.

• Make sure to practice writing Object-C

source code so you can create highly

functioning apps.

57