Mansfield Park 2

advertisement

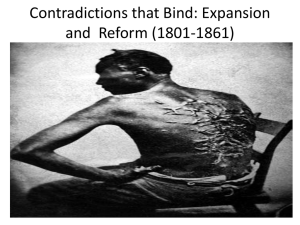

Mansfield Park 2 Outline • Slavery as a ‘dead silence’ in MP • JA and slavery • Fanny Price as ‘spiritual mistress’ of Mansfield Park • Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • Britain on the world stage from 1814 Slavery as a ‘dead silence’ in MP • Said: ‘Antigua and Sir Thomas’s trip there have a definitive function in MP, which … is both incidental, referred to only in passing, and absolutely crucial to the action…. Sir Thomas, absent from Mansfield Park, is never seen as present in Antigua, which elicits at most a half-dozen references in the novel’ (Culture and Imperialism, pp. 106-08) Slavery as a ‘dead silence’ in MP • Said: ‘How are we to assess Austen’s few references to Antigua, and what are we to make of them interpretatively?’ (ibid., p. 106) • Fanny asks Sir Thomas about the slave trade . . . MP, vol. 2, ch. 3 • Fanny to Edmund: ‘Did you not hear me ask him about the slave trade last night?’ ‘I did – and was in hope the question would be followed up by others. It would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of farther.’ ‘And I longed to do it – but there was such a dead silence!’ Slavery as a ‘dead silence’ in MP • Fanny and geopolitics: ‘my cousin cannot put the map of Europe together … my cousin cannot tell the principal rivers in Russia ... she never heard of Asia Minor’ (MP, vol. 1, ch. 2) • Slavery a ‘dead silence’ in MP, therefore not a live issue? JA and slavery • Voyages by Frank Austen (JA’s brother), in 1805 and 1806, to the West Indies (including Antigua) – FA critical of the treatment of slaves in Antigua • JA’s father a trustee of an Antiguan sugar plantation belonging to a close friend from Oxford days JA and slavery • 1772, Lord Mansfield’s ruling (the ‘Mansfield Judgement’): a slave becomes free once he or she (in this case, James Somerset) sets foot on British soil • Women’s writing on slavery during the Romantic era: e.g. Ann Yearsley, ‘A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave Trade’ (1788); Hannah More, ‘The Sorrows of Yamba, or the Negro Woman’s Lamentation’ (1795) JA and slavery • Sir Thomas’s colonialism extends in relation to not just Antigua but also Fanny as his niece • Fanny brought into Mansfield Park by Sir Thomas as a means by which to improve both Mansfield Park itself and his niece Said, Culture and Imperialism, p.110 • ‘What was wanting within was in fact supplied by the wealth derived from a West Indian plantation and a poor provincial relative, both brought into Mansfield Park and set to work. Yet on their own, neither the one nor the other could have sufficed….’ Said, Culture and Imperialism, p.110 • ‘neither the one nor the other could have sufficed; they require each other and then, more important, they need executive disposition, which in turn helps to reform the rest of the Bertram circle. All this Austen leaves to her reader to supply in the way of literal explication’ JA and slavery • Fanny ‘colonized’ by Sir Thomas subsequently embraces the Mansfield regime and rejects her Portsmouth home (the smallness, the impropriety, etc., of the Portsmouth home) • At the same time, Fanny has a positive effect on the Bertram circle (becomes Sir Thomas’s favourite daughter, etc.) Fanny Price as ‘spiritual mistress’ of Mansfield Park • Through Fanny the moral values of the Mansfield regime – symbolically, the landed gentry in general – are regenerated • JA’s emphasis on interdependency as mutually beneficial under the heading of ‘executive disposition’ (i.e. Sir Thomas is reconfirmed as head of the family) Fanny Price as ‘spiritual mistress’ of Mansfield Park • Said: ‘the Bertrams did become better if not altogether good…. all of this did occur because outside (or rather outlying) factors were lodged properly inward, became native to Mansfield Park, with Fanny the niece its final spiritual mistress, and Edmund the second son its spiritual master’ (ibid., p. 110) Fanny Price as ‘spiritual mistress’ of Mansfield Park • But, in the end, who transforms whom? The Bertrams transform Fanny? Or Fanny transforms the Bertrams? • Transformation from below? – Fanny Price’s lower-middle-class status mirrored by JA as herself a clergyman’s daughter Fanny Price as ‘spiritual mistress’ of Mansfield Park • Scott on JA: ‘her most distinguished characters do not rise greatly above well-bred country gentlemen and ladies; and those which are sketched with most originality and precision, belong to a class rather below that standard’ (Critical Heritage, p. 64) Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • A valuable corrective to Said’s ‘transformation from above’ view of Fanny, from Fraser Easton, ‘The Political Economy of Mansfield Park: Fanny Price and the Atlantic Working Class’, Textual Practice, 12/3 (1998), 459-88 Easton, ibid., p. 487 • ‘because [Said] places Fanny in a relationship of adoption or “affiliation”, rather than resistance to the values of Sir Thomas – even calling her the “spiritual mistress” of Mansfield – his analysis of the “geographical problematic” in the novel fails to register Austen’s defence of custom and its anti-imperial inspiration’ Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • Fanny’s return to Mansfield from Portsmouth even more significant than Sir Thomas’s return after his trip to Antigua • MP a novel of two ‘returns’ • The moral values that FP regenerates at Mansfield are those having to do with custom rather than colonialism Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • Easton: ‘When Fanny finally does return to Mansfield, it is not as the exponent of its plantocratic and capitalist values, but as a defender of common life and plebian resistance. Her return signals a change of regime at Mansfield, a change requiring acceptance by Sir Thomas of what is truly foreign about her’ (ibid., p. 482) Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • Easton’s view: throughout the novel the idea of interdependency – or ‘reciprocity’ – that Fanny serves to embody has more to do with a defence of custom than an advocacy of colonialism • For a novelist who is supposedly ‘blind’ to the condition of the servant class JA names a remarkable number of servants in MP Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • Miss Lee, Nanny, Wilcox, Mr Green, John Groom, Mrs Jefferies, Mrs Whitaker, Dick Jackson, Baddeley, Christopher Jackson, Stephen, Charles, Robert, Chapman, Rebecca, Sally, Maddison • Easton: ‘We resist the perspective of labour and service, even when Austen offers it to us’ (ibid., p. 480) Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • From the ‘perspective of labour and service’, what we see in MP is the enactment of forms of plebeian-patrician reciprocity that have been customary within the tradition of rural life • The land owners allow non-monetary social privileges amongst their workers: ‘right of commonage’ – making use of the ‘left overs’ (wood, food, etc.) Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • See also the right to ‘perks’, such as the wooden chips in the Portsmouth dockyard (cf. whiskey as both a gift and a right in CR) • In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the ‘right of commonage’ under threat from parliamentary acts of enclosure (cf. the law as a weapon in CR) • ‘Enclosure’ a form of internal colonization Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • Enclosure in Northamptonshire – the emphasis on privacy at Mansfield Park • Fanny’s plebeian perspective articulated in terms of her strong sense of moral equality – refusal of Henry Crawford’s marriage proposal, for example • Easton: ‘Fanny cannot be bought, there is no “fanny price”’ (ibid., p. 472) Fanny Price and ‘the Atlantic working class’ • Fanny’s sense of moral equality affirmed by JA as novelist (the ‘Cinderella effect’!) • MP as a novel is thus for custom and against colonialism • FP not so much the ‘spiritual mistress’ (Said) of Mansfield Park as a member of ‘the Atlantic working class’ (Easton) – shared class identity of Northamptonshire servants and Antiguan slaves Britain on the world stage from 1814 • Post-colonial and Marxist readings of MP: Said/Easton • How, then, to interpret the ‘dead silence’ about slavery in JA’s novel • Firstly, the ‘silence’ as such not dead in this particular work – the slave trade evidently a live issue in connection with notions of moral equality that circulate around FP (as herself the ‘patron saint’ of the Atlantic working class) Britain on the world stage from 1814 • But at the same time, it remains the case that we here never get past Sir Thomas’s ‘dead silence’ on the slavery issue • No active interrogation of the slave trade, despite the fact that FP ‘longed’ to inquire farther of her uncle about slavery • The above may be said to mark the limit to FP’s ‘plebian perspective’ • Three stages to FP’s development as the ‘Cinderella’ of colonialism . . . Britain on the world stage from 1814 • 1) Putting the map of Europe together • 2) Enquiring in conversation about the slave trade • 3) But, asking searching questions about colonialist practices in the West Indies…? – the fairytale character of FP’s opposition to slavery and imperialism • FP’s ‘dead silence’ on the slavery issue becomes a form of sanction for the production of avowedly imperialist works in a nineteenthcentury ‘age of empire’ (e.g. Kipling as the unofficial poet laureate of the British empire) Britain on the world stage from 1814 • Said: ‘it is genuinely troubling to see how little Britain’s great humanistic ideas, institutions, and monuments, which we still celebrate as having the power ahistorically to command our approval, how little they stand in the way of the accelerating imperial process’ (Culture and Imperialism, p. 97) Britain on the world stage from 1814 • Britain’s ‘accelerating imperial process’ from 1814 . . . • 1814 the year that marks Britain’s ascendancy in Europe and on the world stage – beginning of the end of the Napoleonic wars • 1814 – the year of MP – an important occasion in which to intervene from an anti-imperialist perspective: a missed opportunity for JA to fully spell out her ethic of moral equality Britain on the world stage from 1814 • 1814 also the year in which Walter Scott’s Waverley is published • Waverley a ‘historical novel’ that shows as such an awareness that 1814 is indeed an important year in European history • With his own 1814 novel, WS makes a more decisive intervention than JA on the question of empire?