THE NOUN

The Noun in Modern English has only two

grammatical categories, number and case. The existence of

case appears to be doubtful.

The

noun

grammatical gender.

has

not

got

the

category

of

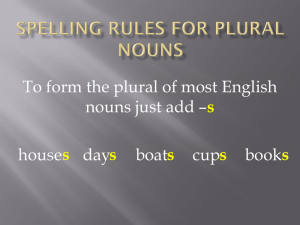

NUMBER

Modern

English,

as

most

other

languages,

distinguishes between two numbers, singular and plural.

The opposition is "one - more than one": table- tables,

pupil- pupils, dog- dogs, etc.

The category of number in English nouns gives rise

to several problems.

Pluralia Tantum and Singularia Tantum

There are two types of nouns differing from all

others in the way of number. The nouns which have only a

plural and no singular are usually termed pluralia tantum

(which is the Latin for plural only), and those which have

only a singular and no plural are termed singularia tantum

(the Latin for singular only).

Among the Pluralia Tantum are the nouns trousers,

scissors, tongs, pincers, breeches; environs, outskirts,

dregs.

On the one hand, among the Pluralia Tantum there

are nouns which denote material objects consisting of two

halves (trousers, scissors, etc.); on the other, there are those

which denote a more or less indefinite plurality.

e. g. environs=areas surrounding some place on all sides;

dregs =various small things remaining at the bottom of a

vessel after the liquid has been poured out of it, etc.

In some cases English and Russian Pluralia Tantum

nouns correspond to each other (trousers - брюки, scissors

- ножницы, environs - окрестности, etc.), while in others

they do not (деньги – money, etc.).

The direct opposite of Pluralia Tantum is the

Singularia Tantum, i.e. the nouns which have no plural

form. Among these we must first note some nouns

denoting material substance, such as milk, butter,

quicksilver, etc., and also names of abstract notions, such

as peace, usefulness, incongruity, etc.

Some nouns denoting substance, or material, may

have a plural form, if they are used to denote either an

object made of the material or a special kind of substance,

or an object exhibiting the quality denoted by the noun.

Thus, the noun wine, milk, denotes a certain substance, but

it has a plural form wines used to denote several special

kinds of wine.

The noun iron (or quicksilver), denotes a metal, but

it may be used in the plural if it denotes several objects

made of that metal (irons - утюги).

The noun beauty (ugliness) denotes a certain quality

presented in an object, but it may be used in the plural to

denote objects exhibiting that quality, the beauties of

nature; His daughters were all beauties.

This is called lexicalization of the plural number.

Here are some other examples:

authority

cloth

colour

custom

damage

development

disturbance

direction

draught

honour

humanity

picture

authorities

clothes

colours

customs

damages

developments

disturbances

directions

draughts

honours

humanities

the pictures

duty

talk

power

work

glass

duties

talks

powers

works

glasses

Collective Nouns and Nouns of Multitude

Certain nouns denoting groups of human beings (family,

government, party, clergy, etc.) and also of animals (cattle, poultry, etc.)

can be used in two different ways: either they are taken to denote the

group as a whole, and in that case they are treated as singulars, and

usually termed "collective nouns"; or else they are taken to denote the

group as consisting of a certain number of individual human beings or

animals, and in that case they are usually termed "nouns of multitude".

My family is small.

My family are good speakers.

The cattle were grazing in the field.

CASE

The problem of case in Modern English nouns is

one of the most vexed problems in English grammar. The

views on the subject differ widely. The most usual view is

that English nouns have two cases: a common case (father)

and a genitive (or possessive) case (father's). Side by side

with this view there are a number of other views, which can

be roughly classified into two main groups:

(1) the number of cases in English is more than two,

(2) there are no cases at all in English nouns….

Case expresses relations between the thing denoted

by the noun and other things, properties, actions, and

manifested by some formal sign in the noun itself. It is

obvious that the minimum number of cases in a given

language system is two, since the existence of two

correlated elements at least is needed to establish a

category.

From this angle, no cases expressed by non-morphological

means can be recognised. It will be therefore impossible to accept the

theories that case may also be expressed by prepositions (i.e. by the

phrase "preposition + noun") or by word order. Such views have indeed

been propounded by some scholars, mainly Germans.

Thus, it is the view of Max Deutschbein that Modern English

nouns have four cases, viz. nominative, genitive, dative and accusative,

of which the genitive can be expressed by the -'s inflection and by the

preposition of, the dative by the preposition to and also by word order,

and the accusative is distinguished from the dative by word order alone.

If prepositions, or word order, or any non-

morphological means of expressing case are admitted, the

number of cases is bound to grow indefinitely. Thus, if we

admit that of the pen is a genitive case, and to the pen a

dative case, there would seem no reason to deny that with

the pen is an instrumental case, in the pen a locative case,

etc.

Thus the number of cases in Modern English nouns

would become indefinitely large. This indeed is the

conclusion Academician I.I.Meshchaninov arrived at.

Thus, the number of cases in Modern English nouns cannot be

more than two (father and father's). The latter form, father's, might be

allowed to retail its traditional name of genitive case, while the former

(father) maybe termed common case, first used by Henry Sweet. Of

course it must be borne in mind that the possibility of forming the

genitive, acc. to Prof. Ilyish, is mainly limited to a certain class of

English nouns, viz. those which denote living beings (my father's room,

George's sister, the dog's head) and units of time (a week's absence,

this year's elections), and also some substantivized adverbs (to-day’s

newspaper, yesterday's news, etc.).

The following views have been put forward on -’s as a case

inflection in nouns:

(1)

when the -'s belongs to a noun it is still the genitive ending,

and when it belongs to a phrase (nobody else’s business, Smith and

Brown’s office) (including the phrase "noun + attributive clause") it tends

to become a syntactical element, viz, a postposition,

Ex: The blonde I had been dancing with’s name was Bernice

something – Crabs or Krebs. /Salinger/;

(2)

since the -'s can belong to a phrase it is no longer a case

inflection even when it belongs to a single noun;

(3)

the -'s when belonging to a noun, no longer expresses a case,

but a new grammatical category; viz. the category of "possession".

Prof. Ilyish concludes that the original case system

in the English nouns is at present extinct, and the only case

ending to survive in the modern language has developed

into an element of a different character - possibly a particle

denoting possession….

The point of view we’ll stick to is that there are 2

cases in English nouns.

GENDER

Gender is a less important category in English than

in any other languages. It is closely tied to the sex of the

referent and is chiefly reflected in co-occurrence patterns

with

respect

to

singular

personal

pronouns

corresponding possessive and reflexive forms.

and

Although there is nothing in the grammatical form

of a noun which reveals its gender, there are lexical means

of making gender explicit, and reference with a third

person singular pronoun may make it apparent.

However, gender is not a simple reflection of

reality; rather it is to some extent a matter of convention

and speaker’s choice, and special strategies may be used to

avoid gender-specific reference at all.

The following lexical means make gender explicit.

There are lexical pairs with male-female denotation, chiefly

among words for family relationships (father-mother, uncle-aunt, etc),

social roles (king-queen, lord-lady, etc.), and animals (bull-cow, cockhen, etc).

The masculine-feminine distinction may also be made explicit

by formal markers:

by separate words, that is lexically: male nurse, a female officer, an

Englishman, a policewoman,

by special morphemes, that is morphologically: actress, tigress,

usherette, proprietrix, heroine)

First, and most importantly, this skewed distribution

reflects societal differences in the typical roles of men and

women, where men still hold more positions of power and

authority than women. Related to this difference, there is

some evidence that speakers and writers simply make

reference to men more often than women.

Second, the differences in language use reflect a

linguistic bias, because masculine terms can often be used as

duals, to refer to both men and women, but not vice versa.

The most common nouns ending in –ess or –er/or

are princess – prince, actress-actor, mistress-mister,

duchess-duke, waitress-waiter, countess-count, goddessgod, hostess-host, stewardess-steward. It is worth noting

that the uniquely feminine terms tend to refer to social

roles of smaller status than most masculine terms.

Thus, 5 of the 7 feminine words with no masculine equivalent

have meanings that are derogatory or denote menial social roles:

beggarwoman, charwoman, ghostwoman, slavewoman, sweeperwoman.

In addition, many of the terms in feminine / masculine word pairs are not

in fact equivalent. Instead, the feminine term often denotes a lesser social

role or something with a negative overtone compared with the masculine

term:

spinster

bachelor

governess

governor

mayoress (the wife of a mayor)

mayor

mistress

master

tigress

tiger

witch

wizard

To be continued