here - rcbsam.com

advertisement

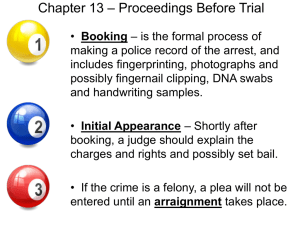

COM 365/665: Journalists, the Courts, and the Law Ron Bishop, Ph.D. Department of Culture and Communication Drexel University Covering Criminal Cases Criminal cases are to most folks more newsworthy than civil cases. Actions offend our sense of justice. Steps in the process are typically secret. District Attorneys, Attorneys General, U.S. Attorneys – the key people. First Judicial District of Pennsylvania Covering Criminal Cases Three main segments of a case: Pretrial Trial Post-Trial Covering Criminal Cases Pretrial: Arraignment Preliminary Hearing Grand Jury Action Jury Selection Covering Criminal Cases Trial: Opening statements Prosecution: Direct examination Prosecution: Cross examination Prosecution: Re-direct examination Motions Rebuttal Covering Criminal Cases Direct examination (Defense) Cross examination (Defense) Re-direct examination (Defense) Motions Rebuttal Summations/Closing arguments Charge Deliberation Verdict Covering Criminal Cases Any point in the proceedings can be the basis for a solid story. Writing at any point, you should include: Charge(s) Complete ID of defendant. Circumstances surrounding the act(s). Summary of previous developments. Sense of what’s next. And don’t forget your “allegedly.” Covering Criminal Cases It all begins with an arrest. In this story, include: Formal charge(s) The plea (guilty? Not guilty? Not guilty by reason of mental defect or insanity?) Bail (higher or lower than requested?) ROR? Behavior of attorneys, defendants, judge. Compelling remarks. Jared Loughner Indictment Jared Loughner Indictment Charges Against Jared Loughner Criminal Case Coverage Examples Yeardley Love – Expert Testimony Yeardley Love – Online Only Settlement Talks Before BP Trial (NYT) Crane Owners Criminal Trial to Start (WP) Freedom of Information Act Enacted in 1966; signed into law by President Johnson. Each state has its own law. Covers only federal or state agencies. Purpose: to put into practice a philosophy of fullest possible disclosure of government records. Each administration has its own take on that: for Ashcroft, the “sound legal basis” take. Freedom of Information Act Between the late 1700s and mid-1960s, access to records kept by federal government unsettled. No guidance from common law or U.S. Constitution. Early 1950s: a push for access laws. Reporters had little recourse when requests for information were denied. Freedom of Information Act 704,394 FOIA requests filed in 2013, up from 651,254 in 2012. 237,682 requests filled entirely; 203,295 filled partially. in 2013. 41,380 requests denied. Backlog is increasing: 95,564 in 2013, 71,790 in 2012. Had dropped from 83,490 in 2011. DOJ oversees agency compliance; OMB handles the fee guidelines. Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act FOIA gives us access to records kept by federal agencies. Doesn’t cover records held by Congress or the courts. They have their own mechanisms. Some executive branch agencies also fall outside the law. And what’s a “record” anyway? Reasons for denial must be explained. Freedom of Information Act Types of information exempt from disclosure: National security “Housekeeping” materials Material exempted by statute Trade secrets “Working papers” Personnel and medical files Law enforcement records Financial regulatory reports Geological data Freedom of Information Act Agency has 20 business days to respond. You can ask for expedited review (10 days). You can appeal a denial; response must come within 20 business days. Types of requesters: commercial, educational/news media, other. Can get a fee waiver if you prove release of info is in the public interest and isn’t in your commercial interest. Doctrine of segregability: after they exempt some parts of document, have to give you what’s left. Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act Works in tandem with Privacy Act of 1974, which prevents government from disclosing info from its files by name. Act also allows us to gain access, challenge, or correct info held about us. OPEN Act becomes law in 2007; clarifies deadlines for responses, imposes penalties for missed deadlines. Obama in 2009 orders agencies to adopt “presumption of disclosure” (Reno) standard. Fine, but how about transparency about interrogation, Gitmo, Bush’s energy plan, warrantless wiretapping, free rein given to banks by the SEC? Freedom of Information Act Kissinger v. Reporters Committee (1980): Just because they moved his records to State after he ended his time as NSA doesn’t mean they were “records.” FBI v. Abramson (1982): Summaries of Nixon’s “enemies list” are exempt, even though summaries weren’t compiled for law enforcement purposes. Freedom of Information Act More recently… The News Press et al. v. U.S. Dept. of Homeland Security et al. (2007): Appeals court rules FEMA must release to FL newspapers the names and addresses of 1.3 million recipients of federal hurricane relief and insurance money. A “powerful public interest” in seeing how well FEMA did its job gearing up for four 2004 hurricanes; outweighs privacy interest of recipients. Freedom of Information Act Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights of the SF Bay Area v. U.S. Department of Treasury (2009): Treasury ordered by federal judge to disclose petitions asking to remove names from list of suspicious people maintained by Office of Foreign Assets Control. OFAC decided there was nothing that could be released – a “categorical exclusion.” Open Meetings Laws All states have ‘em; range from the very good (FL, TN) to the nearly useless (PA). These and federal Government in the Sunshine Act (1976) require officials to meet in public. Doesn’t always mean you can speak, but you can attend – and you have to have notice. Common law, Constitution once again largely silent on the matter. Open Meetings Laws These are clear statements by legislatures that their actions and deliberations should be out in the open. If a provision in a statute is vague, assumption is to grant access. Laws declare either that all meetings are open, or list the agencies that must hold open meetings. The U.S. Congress is excluded, as are advisory bodies, just as in FOIA. Open Meetings Laws …unless you’re talking a special interest advisory committee; these are regulated by the Federal Advisory Committee Act. FACA limits the creation of advisory committees to only those deemed essential. Limits how long they can exist, dictates they only can give advice to executive branch folks. Puts an end to “locker room discussions” by task forces, subcommittees, and working groups (Oh my!); requires committees act in public. Open Meetings Laws As with FOIA and state FOI laws, there are exceptions built into OMLs. Federal law: national security, trade secrets, personal information, law enforcement records, financial information, regulatory information, ongoing litigation. In DE: Criminal investigations; employee evaluations; attorney-client discussions; collective bargaining; real estate transactions; student disciplinary hearings; and attorneyclient meetings. Open Meetings Laws Laws should specify how many officials have to be there. Deliberative stages of decision-making are meetings, and should be open. Social gatherings and chance encounters are NOT meetings. BOTTOM LINE: If public business is discussed, it must be open to the public. Open Meetings Laws OMLs do allow officials to go into executive or emergency session. Can’t usually take final action, though. Must tell you why they need to go into ES. Citizens, reporters can object. Never leave a meeting voluntarily! The punishments for an OML violation aren’t that severe. Open Meetings Laws In many states, if officials take an action at an improperly conducted meeting, it becomes null and void. But boy, do they try… So a NY federal judge can’t hear a plea and issue a sentence in a drug case in her robing room, for example (U.S. v. Alcantara, 2nd Circuit, 2005). We can’t “leave the vindication of a First Amendment right to the fortuitous presence in the courtroom of a public spirited citizen willing to complain about the closure,” the court said. Open Meetings Laws Common Cause v. NRC (1982): The NRC closed two 1981 meetings on its annual budget. Had said they would be open to the public. Cited Exemption 9 of Sunshine Act, which allows closure to prevent frustration of an agency action. District court rules for CC; NRC hadn’t established a “reasonable likelihood of any harm to future agency actions.” Open Meetings Laws DC Circuit affirms; NRC didn’t meet its burden of showing the meetings were lawfully closed. Sunshine Act doesn’t exempt all budget discussions, but specific items could trigger the exemption. What You’re Playing For… Free Press/Fair Trial Assume publicity means biased juries. Yet our recall is limited. Most trial judges don’t see big problems. Free Press/Fair Trial What does it mean to be impartial? Free from dominant knowledge acquired outside the courtroom (U.S. v. Burr, 1807). Not totally ignorant of facts and issues (Murphy v. FL, 1975). Not having a fixed opinion that would prevent an impartial judgment (Patton v. Yount, 1984). Free Press/Fair Trial You can serve on a jury and have opinions if: Those opinions aren’t so closely held that they can’t be put aside. Publicity surrounding the case is not so widespread that it makes your assurances unbelievable. Free Press/Fair Trial So what can a judge do? Voir dire Change of venue Continuance Admonition Sequestration Gag orders Sealing records Free Press/Fair Trial Usually, these cases involve stories about: Confessions Polygraph Tests Past Criminal Record Questioning Witness Credibility Defendant’s Character The Public Mood is Inflamed Some Cases to Consider… Irvin v. Dowd (1961): Defendant can’t get fair trial where there’s a “pattern of deep and bitter prejudice” in the community. Estes v. Texas (1965): TV equipment created too many impediments to a fair trial. Sheppard v. Maxwell (1966): Trial judge’s responsibility to ensure a defendant’s 6A rights aren’t damaged by publicity. Some Cases to Consider… Nebraska Press Assn v. Stuart (1976): Court develops three-part test to evaluate restrictive orders by judges. Belo Broadcasting v. Clark (1981): Fifth Circuit rules the right to inspect and copy judicial documents is not absolute. Publicker Industries v. Cohen (1984): Civil trials, like criminal trials, must be open to the public, the Third Circuit finds. Some Cases to Consider… Press-Enterprise v. Riverside Superior Court (1986): Can close a preliminary hearing only if there is a “substantial probability” that 6a right will be prejudiced by publicity. Washington Post Co. v. Hughes (1991): Fourth Circuit rules that through voir dire, court can identify jurors whose prior knowledge would prejudice their ability to render fair verdict. The Right To Be Left Alone “An American has no sense of privacy. He does not know what it means, There is no such thing in the country.” - George Bernard Shaw The Right To Be Left Alone Is privacy dead? We seem conflicted. A relatively new concept – don’t see it until end of the 19th Century. We tend to blame the press, but business and government do the most damage. 19th Century newspapers helped teach us to vicariously seek status. The Right To Be Left Alone Are we all “public people” to some degree? Part of life in a civilized country? Do we ever want to be truly left alone? Do we know what it means to not be thinking about privacy? Along Come Brandeis and Warren… The starting point for a national discussion. Lashed out at the press. “…instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life.” A person’s home is his or her castle. We should be able to go to court to stop unwarranted intrusions. 1928: Brandeis alone in saying government needs a warrant to conduct a wiretap. Along Come Brandeis and Warren… Message didn’t take right away. Took until the McCarthy Era to get us thinking about excesses in government information gathering. Turns out our officials were acting just like the Communists after all. Concept accepted slowly – some states still don’t recognize the tort. Others have rejected one or more of the… Four Privacy Torts Appropriation Intrusion Publication of Private Facts False Light Publication Appropriation Can’t appropriate someone’s name or likeness – or sound – for commercial purposes without consent. The right to privacy, the right to publicity. There’s a news exception… The “incidental use” rule. Can’t go after parody either – even if an artist takes pictures of Barbie posed naked in a blender, wrapped in a tortilla, and sizzling on a wok (Mattel v. Walking Mountain Prods., 9th Cir., 2003). Intrusion Can’t intrude upon someone’s solitude. Think wiretapping, paparazzi, telephoto lenses. All you have to do is collect the information. The key phrase: “reasonable expectation of privacy.” Publication of Private Facts Can’t run private information about a person if it would be highly offensive to a reasonable person… …and is not of legitimate public concern. Not endorsed/recognized in some states (NC, for example). Plaintiffs rarely win. Wouldn’t be missed, say some scholars. Publication of Private Facts Must be newsworthy. Plaintiff must prove: Publicity about private facts. It’s offensive to a reasonable person And not of legitimate public concern. Information in public records doesn’t count. A Public Place… False Light Publication Creates a false or erroneous impression of someone. Has to offend; have to prove fault. Lots of disagreement here. Have to prove: Facts are substantially false. Allegations are offensive. Defendant was at fault False Light Publication Minor errors by journalists don’t cut it. Yet most FL suits are based on errors, editing mistakes. Don’t use unrelated photos. And always get a signed release (unless it’s a timely news event). Some Cases to Consider… Bartnicki v. Vopper (2001): High Court says removing incentive for parties to intercept private conversations doesn’t justify applying law to innocent disclosure of information… Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Co. (1979). High Court finds you can’t punish truthful publication of a juvenile’s name when the information was lawfully obtained. Some Cases to Consider… Cox Broadcasting Co. v. Cohn (1975): Justices rule barring publication simply because it might offend a “reasonable person” would make it too hard for the media to inform. Virgil v. Time, Inc. (9th Circuit, 1975): The line between private and public information is drawn when publicity changes from furnishing information to “morbid and sensational prying.” Some More Cases to Consider… Cantrell v. Forest City Publishing (1974): But if you know what you’ve published is untrue, as here – that’s reckless disregard. Booth v. Curtis Publishing (NY, 1962): Use of your name or likeness in an ad for a publication is not appropriation if it was originally part of the information content. Some More Cases to Consider… Time, Inc. v. Hill (1967): Information seen in the media is not there for trade purposes, the High Court rules. Can’t use NY’s privacy law to recover for false reports of newsworthy matters absent reckless disregard. Dietemann v. Time, Inc. (1971): CA court finds a homeowner shouldn’t have to risk that what happens in the home will be recorded and disseminated. BUT you can’t make a case for intrusion if you were acting in your official capacity. Some More Cases to Consider… Duncan v. WJLA-TV (1984): FL court reinforces idea that you shouldn’t use an unrelated photo or footage to make a point in your story. People’s Bank and Trust Co. v. Globe International (1992): Arkansas court reminds us to not use photos of real alive people when writing about someone else. Some More Cases to Consider… Desnick v. ABC, Inc. (1993): Newsgathering methods might be distasteful, but they are “entitled to all the safeguards with which the Supreme Court has surrounded liability for defamation.” Doe v. New York (2nd Circuit, 1994): Information found in public records is not private – publishing it can’t sustain a private facts claim. Some More Cases to Consider… Food Lion, Inc. v. Capital Cities/ABC (1996): You don’t have to claim intrusion to win. Reeves v. Fox Television Network (1997): The arrest of a man featured on “COPS” was a matter of public concern and thus not a privacy violation. Shulman v. Group W Productions (1998): A conversation taped when you’re being extricated from a car after an accident is an intrusion, CA Supreme Court finds. One Last Case to Consider… Campus Communications v. Earnhardt (2003): Newspapers drop challenge to new state law restricting access to autopsy photos. Earnhardt Family Protection Act requires autopsy photos, video and audio recordings be kept confidential. The Post-Tinker Era Remember these words: order and disruption. Tinker v. Des Moines School District (1969): students don’t leave their right to free expression “at the schoolhouse gate” – or metal detector. So long as they don’t interfere with the “requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school” or “collide with the rights of others.” Hazelwood SD v. Kuhlmeier (1988): Well, turns out you can censor a HS newspaper for publishing controversial articles so long as you are acting on “legitimate pedagogical concerns.” Where the hell was the press when the Court ruled? The Post-Tinker Era Kincaid v. Gibson (2000): 6th Circuit offers hope; can’t seize college yearbooks just because you don’t like the content and color of the cover. Yearbook is a limited public forum – only valid TPM rulings allowed. Dean v. Utica Community Schools (2004): School paper again called a limited public forum. There was no policy of prepub review, no regulation of subjects by advisor. Can’t censor because you have a differing opinion. The Post-Tinker Era Bethel SD 403 v. Fraser (1986): Hold on thar! Court rules lewdness, vulgarity, offensiveness isn’t protected. We need to protect you from that fucking stuff. Johnson v. New Brighton Area SD (2008): “If I were Osama, I would already have pulled a Columbine” is not protected speech. Wasn’t pure speech, as in Tinker. Officials acted on what they reasonably thought was a disruption…they were fighting words! Morse v. Frederick (2004): The quality of an argument does matter, the Court rules. Can’t promote drug use and try to gain publicity while doing so! A school environment has “special characteristics.” And What About College? Capeheart v. Hahs (2012): Seventh Circuit will soon rule on whether faculty members lose their ability to speak freely when they are employees of public universities. Professors and instructors play a unique role in advancing knowledge – a “transcendent value” – not just for folks in classroom, but for everyone. If the Seventh Circuit upholds lower court, professors will risk their careers if they speak out. The Court’s decision in Garcetti just doesn’t apply, Capeheart argues. To Sue or Not to Sue… In the 1980s through the early 90s, media was swamped by libel suits. In 1996, the successful defense rate was 28.5 percent. Plaintiffs felt emboldened. At that time, the median award was $2.38 million – the highest ever. Now about $3.4 million. A huge cost involved in defending a suit. To Sue or Not to Sue… Suits are less frequent. News organizations winning more often. Defendants win, or have a verdict overturned on appeal about 80 percent of the time. Number of trials has dropped. Media’s success against public figures has increased. To Sue or Not to Sue… Not ready to pop the champagne, though. Huge awards are still damaging to media companies, especially small ones. Former McClennan County (TX) DA Vic Feazell won $58 million in 1991 against WFAA-TV. Station accused him of taking bribes to settle drunk-driving cases. Broke previous record of $34 million in suit by former Philly ADA Richard Sprague against PNI. Reporter had been prosecuted by Sprague for illegal wiretapping and vowed to “get” Sprague. To Sue or Not to Sue… In 1997, federal jury awards a defunct bond brokerage firm $222.7 million ($200 in punitives; $22.7 million in compensatories). Articles in WSJ claimed firm defrauded LA State Employees Pension Fund. Several statements were false, but judge tossed out punitive damages, saying there was no evidence of actual malice in the WSJ’s reporting. Let compensatory damages stand. What is Libel? Publication or broadcast of a statement that injures someone’s reputation, or that lowers that person’s esteem in the community. To Sue or Not to Sue… Folks on juries are getting tougher on personal injury plaintiffs. We may be beginning to question the huge damage awards. Cost is passed on in form of higher insurance rates. Libel: The Basics Defamation: any communication that holds a person up to contempt, hatred, ridicule, or scorn. How Do I Win? Libel was published. Publication was about the plaintiff. Material was defamatory. Material was false. Defendant was at fault.