Hyslop Orthography LSA2011

advertisement

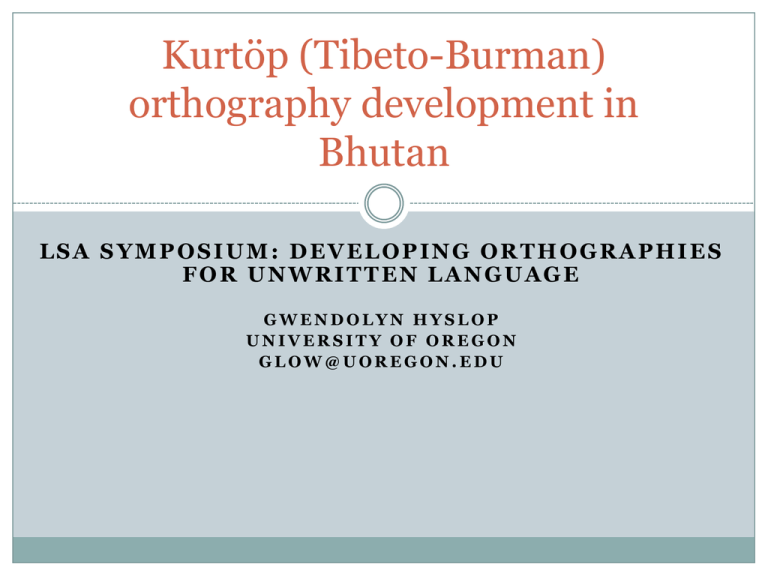

Kurtöp (Tibeto-Burman) orthography development in Bhutan LSA SYMPOSIUM: DEVELOPING ORTHOGRAPHIES FOR UNWRITTEN LANGUAGE GWENDOLYN HYSLOP UNIVERSITY OF OREGON GLOW@UOREGON.EDU Outline • Introduction to Kurtöp and literacy in Bhutan • Factors involved in orthography development in Bhutan • • • • • • ‘Deep’ vs. ‘shallow’ representation ‘faithful’ representation Government expectations Script choice (Roman-based vs. ’Ucen-based) Religion (Buddhism) National language (Dzongkha – linguistically a Tibetan dialect) Kurtöp • Kurtöp is a previously undescribed Tibeto-Burman language of Bhutan (Hyslop 2011 is first grammatical description) • About 15,000 speakers in Northeastern Bhutan • No monolingual speakers. Most fluent in Dzongkha (national language) as well as Tshangla (unwritten lingua franca of eastern Bhutan), Nepali and many are also fluent in Hindi and English. • Mainly literate in Dzongkha and English Kurtöp Linguistic Factors • ‘Deep’ vs. ‘shallow’ representation: • Relatively simple and predictable allomorphy on case enclitics and verbal suffixes. • e.g. perfective -pa ~ -wa ~ -sa • e.g. hortative -ki ~ -ci ~ -iki • Consensus among community members to represent allomorphy in all examples. Linguistic Factors • How much to represent: • Tone and vowel length are contrastive, though not terribly robust. High/low tone contrasts following sonorants. Long/short contrasts in open syllables. • Again, speaker consensus to represent the contrasts. Governmental Policies • Linguistic research in Bhutan is necessarily collaborative and thus so is orthography development. • The government requires both Roman and ’Ucenbased orthographies. • ’Ucen is the Tibetan-based orthography (abugida) derived from Brahmi in the 7th century Tshui and Joyi versions of ’Ucen <tshugs.yig> tshui <mgyogs.yig> joyi Buddhism and ’Ucen • Buddhism is a state religion in Bhutan. • Buddhist texts, written in ’Ucen (Tshui) are sacred. • As extension, anything written in ’Ucen is often considered sacred • As such, issues surrounding ’Ucen are very sensitive Background: The ’Ucen syllable Background: The ’Ucen syllable In the Classical Tibetan Orthography, syllables are represented according to this diagram. The “R” represents a simple onset, or in the case of an onset-less syllable, the vowel. C1, C2, and C4 may be used to add consonants to the onset, making it complex. The V slots are for vowels. C3 represents a single coda (if present) and C5 makes a complex coda (rarely occurs). Classical Tibetan <bsgrubs> <bsgrubs> For example, to write <bsgrubs> The complex onset is <b> in C1; <s> in C2 position, <g> in root position; <r> in C4. /u/ is represented below C4. <b> in C3 and <s> in C5 indicate the complex coda. ’Ucen and Tibetan/Dzongkha Classical Tibetan phonology had around 28 consonants (labial, dental, palatal, velar). And complex onsets And five vowels No tone ’Ucen and Tibetan/Dzongkha After almost 1,400 years of change, Lhasa Tibetan (the prescribed standard) has: A new series of retroflex consonants Two new vowels (front high and mid rounded) High and low tonal registers; level and falling tonal contours Changes in voicing/aspiration contrasts Simplified onsets ’Ucen and Bhutan The modern use of ’Ucen assumes the 1400 years of change from Classical Tibetan to modern Lhasa Tibetan. ’Ucen is used this way in Bhutan; for example, words with complex onsets in Classical Tibetan are still written as such in modern Tibetan/Dzongkha, but not pronounced as such. Representing any pronunciation using ’Ucen entails the reader to infer the sound change. There is no way to represent various aspects of the phonology of other synchronic Bhutanese languages – such as complex onsets – in the history of Bhutanese education. Contemporary <bsgrubs> <bsgrubs> After approximately 1400 years of change, <bsgrubs> is pronounced: ɖùp Kurtöp phonology Kurtöp complex onsets Some problems But in Kurtöp pra = ‘monkey’ Some problems Idea 1: Use ’Ucen in a way similar to Roman. <pra> How to represent vowels other than /ɑ/? Problems, continued This would be confused with /lé/ in Dzongkha/Tibetan conventions <ble> <bele> This leads people to tend to pronounce the word correctly, but does not follow the traditional conventions and is unattractive. Proposed solution Based on existing (but rarely used) conventions established in Tibetan to represent different languages. Should not affect Dzongkha transference issues Aesthetically pleasing Kurtöp speakers find it intuitive and easy to read Proposed solution Existing computer fonts do not allow the needed combinations Chris Fynn, DDC font developer, agreed to adapt the Bhutan ’Ucen fonts (joyi and tshui) to accommodate the new combinations In addition to the complex onsets, the adapted fonts will be able to mark tone Proposed solution Tshui font is finished and joyi is scheduled to be finished by March. /ká/ /khí/ /gú/ /ŋé/ /có/ /c/ /kja/ /ʈa/ /kra/ /kla/ /klwa/ Summary Kurtöp speakers preferred a shallow and faithful representation -- for both Roman and ’Ucen based orthographies. With regard to ’Ucen, the cursive, or Joyi, version was preferred, due to its somewhat neutral religious affiliation and its status as an indigenous script. Reading rules from Tibetan/Dzongkha posed serious problems for Kurtöp, which is not a direct descendent from Classical Tibetan and has a different phonology. Summary Adapting ’Ucen to fit Kurtöp phonology required considerations in: transference from Dzongkha readability usability aesthetics standard conventions historical uses of ’Ucen religious sensitivity (e.g. representing Classical Tibetan religious borrowings, script choice) Acknowledgements Research on Kurtöp has been funded by the National Science Foundation and the Endangered Languages Documentation Project. All research and orthography development has been done in collaboration with the Dzongkha Development Commission in Bhutan. I am also grateful for discussion with and comments from Karma Tshering, Kuenga Lhendup, Scott DeLancey, Keren Rice, and Kris Stenzel. Thank you!