aesop - English 630 - Professor Mueller

advertisement

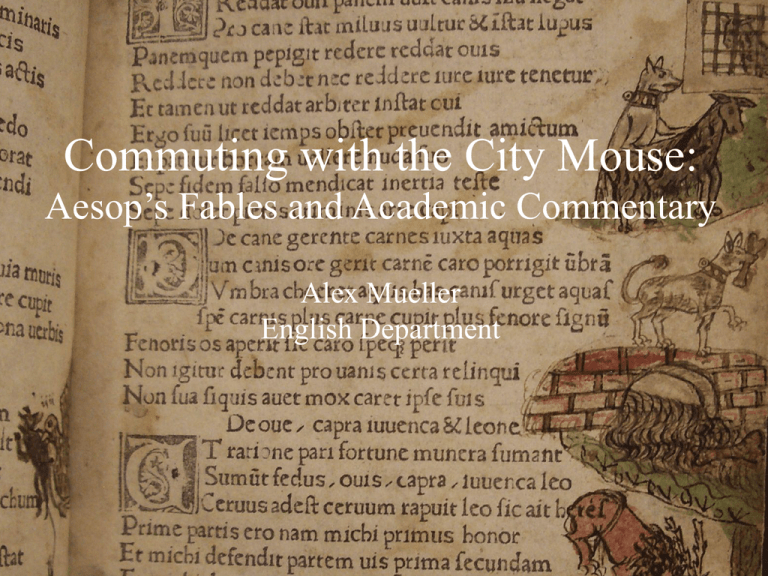

Commuting with the City Mouse: Aesop’s Fables and Academic Commentary Alex Mueller English Department The City Mouse and the Country Mouse It is better to live in self-sufficient poverty than to be tormented by the worries of wealth. Aesop in the Medieval Classroom Codex Vindobonensis Palatinus 303 Promythium for “De lupo et agno” [The wolf and the lamb] (fol. 13r): . . . Sursum bibebat lupus Sursum bibebat lupus longeque inferius agnus. [The wolf was drinking upstream the wolf was drinking upstream and the lamb a long way downstream.] [omits the following “moral”] Haec in illos dicta est fabula qui hominibus calumniantur" [this fable is written about those who falsely accuse others] Heinrich Steinhöwel’s Aesop • First printed as a bilingual edition (German/Latin) by Johann Zainer at Ulm in 1476/1477. •Translated into several languages, including French, Dutch, and Spanish. •Base text for William Caxton’s English Aesop in 1481. •Expanded to 300 fables by schoolmaster Sebastian Brant for 1501 printing. Esopus moralizatus Printed in Reutlingen by Michael Greyff (23 July, 1489). This copy (99975) is currently held in the Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Note: The commentary for each fable begins in the margin and then concludes below the fable text. Esopus Moralizatus Printed in Cologne by Heinrich Quentell (23 Mar., 1489) This copy (99974) is currently held in the Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Note: In contrast to the previous example, this edition only contains commentary below each fable. Earlier Commentary on the elegiac Romulus Klosterneuburg, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex Claustroneoburgensis 1093, folio 349v (mid-15th century) Note: The commentary to the verse prologue begins in the margins [bottom right], . . . . . completely fills the next folio, and continues onto the following leaf, surrounding the second half of the verse prologue [below middle right] (fol. 350v-351r). The Crow and the Water Jar A thirsty crow noticed a huge jar and saw that at the very bottom there was a little bit of water. For a long time the crow tried to spill the water out so that it would run over the ground and allow her to satisfy her tremendous thirst. After exerting herself for some time in vain, the crow grew frustrated and applied all her cunning with unexpected ingenuity: as she tossed little stones into the jar, the water rose of its own accord until she was able to take a drink. This fable shows us that thoughtfulness is superior to brute strength, since this is the way that the crow was able to carry her task to its conclusion. Medieval Commentary on “The Crow and the Water Jar” Copenhagen, Gl. Kgl. Saml., 1905 4o (14th century) Ingentem. Hic docet quod ingenium preualet uiribus, et hoc per coturnicem que dum sitiret in quodam campo urnam semiplenam aqua inuenit, quam uiribus inclinare non potuit. Sed eam ingenio lapillis inpleuit et istam aquam extraxit. Fructus talis est: Melior est sapiens forti uiro (fol. 139r). [Ingentem. Here he teaches that cleverness is better than strength; and he teaches that through a quail, which, when it was thirsty, found an urn half-full of water in a field, and it could not tip the urn. But using its cleverness, it filled it with stones and drew out the water. The moral is this: The wise man is better than the strong.] The Fourfold Model of Medieval Exegesis Venice, Biblioteca Marciana MS 4018 (14th century) Lictera gesta refert, quod credas aligoria Moralis quod agas, quod speres anagogia. [The literal presents the acts, the allegorical that which you ought to believe, the moral what you ought to do, the anagogical what you ought to hope.] More Medieval Commentary on “The Crow and the Water Jar” Wrocław, Bibl. univ., ms. cod. Q.126 (15th century) in hoc appologo docemur quod multa sunt que citius fiunt per artem quam per vires(fol. 130r). [in this fable we learn that there are many things which can be done more quickly by skill than by strength.] Even More Medieval Commentary on “The Crow and the Water Jar” Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Preußischer Kulturbestiz, cod. Q 536 (15th century) Hic monet nos ut studiosius acquiramus scientiam quam vires, quia magis proficit (fol. 9r). [Here he urges us that we be more eager to acquire knowledge than power, because it is more useful] Proverbial Elaboration upon Medieval Commentary on “The Crow and the Water Jar” Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, cgm 3974 (15th century) Vnde: Homo sepe vincit illa per sapientiam que per vires non faceret. Eciam monet nos ut studiosius sapientia et ingenio insistamus magis quam viribus (fol. 228v). [Whence the saying: A man often conquers with knowledge those things that he could not do by force. This also urges us to rely more on wisdom and cleverness than on strength.] Homiletic Elaboration upon Medieval Commentary on “The Crow and the Water Jar” Budapest, Magyar nemzeti múzeum, ms. lat. med. aev. 123 (15th century) In hoc appollogo auctor docet nos quod queramus prudenciam, dicens “Tu debes scire quod prudencia est maior viribus et prevalet eam, quia per sapienciam vincet homo qui viribus vincere non posset.” Ideo subiungit dicens quod sapiencia complet opus cuiuslibet hominis inceptum. Vnde Salomon Prouerbiorum: “Potencior est sapiencia”(fol. 15r). [In this fable the author teaches us that we should seek knowledge, saying, "You should know that knowledge is greater than strength and more valuable, because with wisdom a man can conquer what he cannot conquer with strength." He continues saying that wisdom accomplishes the task begun by anyone. Thus Solomon in the Proverbs: "Wisdom is stronger.”] Commentary Revising Fable: “The Crow and the Water Jar” Prague, Universitní Knihovna, ms. 546 (15th century) Ingentem sitiens. Hic actor ostendit quod prudencia est melior et maior viribus. Ergo studiosius admonet ut sciamus et prudenciam acquiramus, quod probat dicens: Quedam sitiens cornix volans per campum venit ad vnum fontem, quem circa vidit pendere vnam vrnam in qua modicum aque fuit, quam haurire non valebat. Post hec cupiens effundere vrnam planis campis, quia cornix nusquam potuit inclinare, tandem invenit sua arte calliditatem, et congregans lapillos in vrnam misit. Quibus immissis aqua sursum ascendit et sic habuit facilem viam potandi (fol. 22r). [Ingentem sitiens. Here the author demonstrates that wisdom is better and greater than strength. Thus he urges us quite eagerly that we know that we should seek wisdom, which he shows by saying: A thirsty crow, flying across a field, came to a well, above which it saw a bucket hanging in which there was little water, which it could not pour out. Then, hoping to spill the vessel onto the ground, because the crow could not tip it, it nevertheless thought up a strategy in its cleverness; and gathering pebbles it dropped them into the bucket. When they had been put in, the water rose up, and thus the crow had an easy way to drink.] “The Crow and the Water Jar” as a Metaphor for the Collaborative Construction of Knowledge Erfurt, Stadtbücherei, Amplon.Q.21 (15th century) Licet sicud cornix non potuit effundere vrnam, sic nullus scholaris studens potest quamlibet scientiam acquirere; set potest acquirere aliquam partem scientie si proiciat lapidem, id est si adhibit laborem et dilegenciam (fol. 35r). [Just as the crow could not spill the urn, so no student can attain any knowledge he desires; but he can acquire a certain portion of knowledge if he throws in a stone, that is to say if he applies effort and diligence.] “The Crow and the Water Jar”: Writing as Accumulating "Novus Avianus" Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, clm 14703 and Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cpv 303 Versus cev scribit, taliter arte bibit (10). [In the same way as the author writes verses, so the crow drinks by skill.] “The Crow and the Water Jar”: Rhetorical Amplificatio or Elaboration Geoffrey of Vinsauf Documentum de modo et arte dictandi et versificandi [Instruction in the Art and Method of Speaking and Versifying] sic ex modica maxima crescit aqua. [And so, from a little water, much water arises.] Uncertain Amplificatio in English: Robert Henryson’s Morall Fabillis This cok . . . may till ane fule be peir. (141-2) [This cock . . . may be compared to a fool.] this cok weill may we call Nyse proude men. (590-1) [this cock well may we call foolish, proud men.] This volf I likkin to sensualitie. (1118) [This wolf I liken to sensuality.] This selie scheip may present the figure Of pure commounis. (1258-9) [This innocent sheep may represent the figure of the poor commoner.] The City Mouse and the Country Mouse: Henryson’s Commentary Blissed be sempill lyfe withoutin dreid; Blissed be sober feist in quietie. Quha hes aneuch, of na mair hes he neid, Thoct it be littill into quantatie. Grit aboundance and blind prosperitie Oftytmes makis ane euill conclusioun. The sweitest lyfe, thairfoir, in this cuntrie, Is sickernes, with small possessioun. Thy awin fyre, freind, thocht it be bot ane gleid, It warmis weill, and is worth gold to the; And Solomon sayis, gif that thow will reid, "Vnder the heuin I can not better se Than ay be blyith and leif in honestie.” Quhairfoir I may conclude be this ressoun: Of eirthly ioy it beiris maist degre, Blyithnes in hart, with small possessioun. (373-96) [Blessed be a simple life without fear; blessed be a temperate feast in peace. Whoever has enough, though it is little in quantity, has Of wantoun man that vsis for to feid no need of more. Great abundance and blind prosperity often Thy wambe, and makis it a god to be; produce a bad conclusion. Therefore, in this country the sweetest Luke to thy self, I warne the weill on deid. life is security with modest possessions. O greedy man, accustomed to feed your stomach and make it a god, look to The cat cummis and to the mous hes ee; yourself, I warn you in all earnest. That cat comes, and has an eye on the mouse. What is the use of your feasting and splendor, with Quhat is avale thy feist and royaltie, a fearful heart and tribulation? Therefore, the best thing on earth, I With dreidfull hart and tribulatioun? say for my part, is a merry heart with modest possessions. Your Thairfoir, best thing in eird, I say for me, own fire, friend, though it is only a coal, warms well, and is worth gold to you. And Solomon says, if you care to read him, "Under Is merry hart with small possessioun. the heaven I can see nothing better than to be always happy and live virtuously." Wherefore, I may conclude with this saying: "The highest degree of earthly joy comes from blitheness of heart, with modest possessions."] Fable Commentary as “Writerly Text” Because the goal of literary work (of literature as work) is to make the reader no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text. Our literature is characterized by the pitiless divorce which the literary institution maintains between the producer of the text and its user, between its owner and its consumer, between its author and its reader. Roland Barthes, S/Z, trans. Richard Miller (New York: Hill and Wang, 1974), 4. Fable Commentary as Hypertext By “hypertext,” I mean non-sequential writing – text that branches and allows choices to the reader, best read at an interactive screen. As popularly conceived, this is a series of text chunks connected by links which offer the reader different pathways. Theodor H. Nelson, Literary Machines (Swarthmore, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1981), 0/2. The Wisdom of the City Mouse? My dear fellow, you could never find such delicious food as this anywhere else in the world ...