SENTENCING GUIDELINES IN THEORY AND PRACTICE: THE

advertisement

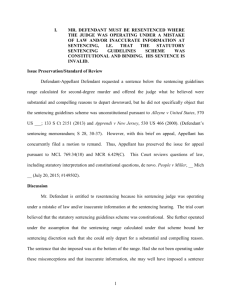

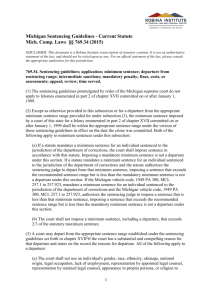

SENTENCING IN THEORY AND PRACTICE: THE ENGLISH GUIDELINES EXPERIENCE Andrew Ashworth, University of Oxford English Guidelines – Brief History • Guideline judgments delivered by Lord Chief Justice: • • • • • Aramah (1982), Boswell (1984) Magistrates’ Association’s guidelines (1989) ‘Guidelines not tramlines’: achieving consistency but allowing discretion Creation of Sentencing Advisory Panel (1998) giving advice to Court of Appeal Sentencing Guidelines Council (2003) to issue definitive guidelines; now Sentencing Council Gradualism: by offence groups, and general principles Structure of English Guidelines • Sentencing guidelines without a grid: an alternative to • • • • U.S. approaches A. divide each offence into 3 or 4 bands (levels of seriousness), and assign sentence ranges to them B. identify a starting-point for each band C. create a step-wise process that includes all the major decisions a court must make when passing sentence. * Not a two-stage approach, but a nine-stage approach * Step 1: Determining the offence category • Three categories / bands / levels • 1 – greater harm and higher culpability • 2 – greater harm + lower culpability OR lesser harm and higher culpability • 3 - lesser harm and lower culpability • Placement in one category by taking account of the main factors of HARM and CULPABILITY • Example: Assault occasioning Actual Bodily Harm 6 Step 2: Starting point and category range • Using the starting point for the category decided at Step • • • • 1, move the offence upwards or downwards according to the aggravating and mitigating factors relevant to the case ‘Relevant recent convictions are likely to result in an upward adjustment’ ‘In some cases, having considered these factors, it may be appropriate to move outside the identified category range’ – DISCRETION See all guidelines at: www.sentencingcouncil.judiciary.gov.uk Step 2 – category ranges 8 Step 2 details Flexibility at steps 1 and 2 • Aggravating factors (e.g. ‘under influence of drugs’) and mitigating factors (e.g. ‘true regret’): individualization • Duty to ‘treat each previous conviction as an aggravating factor’ if court considers that it is relevant and recent and should be so treated; but how much should they aggravate? • Examples: Roberts [2012] EWCA Crim 2729, distraction burglary of elderly woman, 72 precons; Thomas [2013] EWCA Crim 1084, theft of purse containing £80, 66 precons. Departure test • Pre-2010, duty to ‘have regard to’ guidelines • Now, ‘must follow’ any sentencing guideline relevant to the case, unless ‘contrary to interests of justice to do so’ • BUT ‘must follow’ applies only to the offence range, not to the category range: thus, for assault occasioning actual bodily harm, the offence range is from a Band A fine up to 3 years’ imprisonment. • This leaves courts with considerable discretion (subject to appeal court supervision, esp. on category range), and makes true departures very rare. BUT grounds for appeal if judge placed offence in wrong category range, or too high within category range, etc. 12 English Guilty Plea Guideline Crown Court Sentencing Survey (Sentencing Council 2012) Intermediate cases Late plea cases 89% 37% 12% 21% - 32% 9% 34% 9% 11% - 20% 2% 22% 24% 1% - 10% 0% 6% 49% No reduction 0% 1% 6% Guideline recommended reduction 33% 25% 10% Expected sentence reduction 32% 23% 13% 1/3 or greater Early plea cases Totality and Step 6 • Multiple offences: ‘a total sentence which reflects all the • • • • offending behaviour and is just and proportionate.’ Sentencing Council, Offences T.i.C and Totality (2012) Example: Hartley et al [2011] EWCA Crim 1957, continuous course of counterfeiting Cf. Pearce, aggregate sentence must be ‘a just and proportionate measure of the total criminality involved.’ Use of previous decisions as comparators, e.g. Dunks v. Western Australia (2009) 195 A Crim R 130 Is this an ‘instinctive synthesis’? The sentencer’s (bounded) discretion • Deciding the starting-point, taking account of aggravating • • • • and mitigating factors (steps 1 and 2) and any previous convictions: the breadth of discretion and judgment E.g. ‘We further emphasise that the fact-specific nature of the criminal activity involved in each offence remains the paramount consideration.’ per Lord Judge CJ in Thomas [2011] EWCA Crim 1497, at [62]. Reduction for guilty plea (if applicable) Application of totality principle However, courts are NOT free to disagree with guidelines: Healey [2012] EWCA Crim 1005, at [5] per Hughes LJ: The sentencer’s duty • ‘There is deliberately built into the guidelines issued by the Sentencing Council a good deal of flexibility … [for judges]. It does not, however, extend to deliberately disregarding the guidelines, not on the grounds that the case has particular facts that warrant distinguishing it from the general level, but because the judge happens to take a different view about where the general level ought to be. The latter approach is demonstrably unlawful.’ • ‘Very few judges are fortunate enough to go through life without encountering rare occasions when they would prefer the law to be otherwise to that which it is. The judge’s duty is nevertheless to apply it, whether at first instance or in this Court, just as it is the duty of the citizen to obey the law whether he happens to agree with it or not.’ Sentencing for public consumption? • Guidelines, ranges and starting points = ‘transparency’ • Arithmetical approach? The guilty plea discount and the ‘sliding scale’. Cf. Caley [2012] EWCA Crim 2821 on ‘first reasonable opportunity’, ‘overwhelming case’ and Newton hearings, and Thomson (2000), 25% reduction for plea at earliest opportunity. • Sentencing hate crimes: court must specify the quantum of uplift for racial or religious aggravation: Kelly and Donnelly [2001] EWCA Crim 170, at [63]. • Should this approach be taken any further? Could it be applied to more aggravating and mitigating factors? Re-Assessing Sentencing: No Prison for Property Offences? • Sentencing Council’s duty to re-assess sentence levels • • • • and relativities, and to canvas public views Challenge of prison for ‘pure’ property offences, amounting to 8% male and 21% female prisoners. Prison as most severe sanction, right to property much less strong than right to liberty, alternative punishments. Previous convictions as key battle-ground: survey of shop thieves, average of 42 precons Ashworth v. Leveson, and the Sentencing Council’s upcoming guideline on fraud. E&W Guidelines: Success or Failure? • Guidelines as a means to an end • Enabling correctional resource predictions? • Acceptable balance between a) consistency of starting- • • • • • points and b) discretion to enable ‘fact-specific’ sentencing? Too constraining, or too loose? Too complicated and too heavy? Greater transparency, and shield for unpopular sentences Failed to discourage politicians from enacting more mandatory minimum sentences Judges in control?