Speech_and_thought_presentation_final

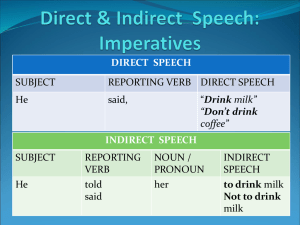

advertisement

Speech and thought presentation Based on Leech and Short’s study in “Style in Fiction” (1981) Analysis of Joyce’s short story “Eveline” (1914) Francesca Bellante Maria Vagheggini Wang Hui Zhao Weichen Introduction Speech and thought presentation can be a problematic area of investigation, especially when it comes to discourses which can’t be fitted into traditional categories [ =direct/indirect speech/thought]. Three main areas of discourse analysis are newspaper reporting, use of citations in academic discourse and study of literature, which is the one we are going to focus on. Areas of discourse analysis Newspaper reporting The focus in the literature has been on manipulative aspects of reporting, which involves an investigation of the way the reported message is expressed—how and why reports may differ from the original, of the source—whether or not the report is attributed to a specific source (and why), and of the reporter's attitude (often conveyed indirectly rather than explicitly stated) towards what is being reported. Areas of discourse analysis Use of citations in academic discourse Because of the highly developed set of conventions for signalling citations [fig. 1], is usually quite simple to identify whether a stretch of language can be counted as a language report or not; however, there are some cases of ambiguity even in quotations in academic discourse. fig. 1 Areas of discourse analysis Study of literature Main categories: - Narrative Report of Speech/Thought Act (NRSA/NRTA) - Indirect Speech/Thought (IS/IT) - Free Indirect Speech/Thought (FIS/FIT) - Direct Speech/Thought (DS/DT) - Free Direct Speech/Thought (FDS/FDT) Narratorial “Interference” When a novelist reports the occurrence of some act or speech act we are apparently seeing the event entirely from his perspective. But as we move along the cline of speech presentation from the more bound to the more free end, his interference seems to become less and less noticeable until he apparently leaves the characters to talk entirely on their own. (Leech and Short 1981) Narratorial “Interference” (Leech and Short 1981, 260) “Eveline”, James Joyce "Eveline" is a story by the Irish writer James Joyce, featured on his 1914 collection of short stories Dubliners. The whole story is presented from Eveline’s perspective and recalls the steps leading to her final decision to not escape with her lover, Frank, a sailor who offers to take her to Buenos Ayres in order to save her from the abusive father. DS/IS (Leech and Short 1981, 255) Converting DS -> IS Inverted commas, which mark quotation as syntactically independent of the reporting verb “said”, are removed, making the reported speech dependent on the reporting verb. That dependence can be marked explicitly by the introduction of a subordinating conjunction (e.g. “he said that…”) The first- and second-person pronouns change to third-person The tense of verbs undergo ‘backshift’, as do time adverbs (e.g. “Now I see” -> “then he saw”) ‘Close’ deictic adverbs (e.g. “here”) change to more remote (e.g. “there”) (Leech and Short 1981, 256) Converting DS -> IS The effect of these changes is to remove all those features which are directly related to the embedded speech situation only and to subordinate the reported speech to the verb of saying. N.B. There can be occasions in conversations (though these are relatively rare in the novel) where some of the extra linguistic referents will be the same for both the primary and the secondary speech situations. The relevant deictic can then remain unchanged. (Leech and Short 1981, 256) E.g. “What did Carlo say?” “Carlo said that he will come here tomorrow.” Conversion IS->DS He had fallen on his feet in Buenos Ayres, he said A reader faced with an indirect string cannot automatically infere the original direct speech; the sentence above could be an indirect version of any of the following: [1] ‘I have fallen on my feet in Buenos Ayres.’ [2] ‘Against all odds, I made my fortune in Buenos Ayres’ [3] ‘When I arrived in Buenos Ayres, I finally landed on my feet.’ Free Direct Speech (FDS) Direct speech has two features which show evidence of the narrator’s presence, namely the quotation marks and the introductory reporting clause. It is possible to remove either or both of these features, and produce a freer form, where the characters apparently speak to without the narrator as an intermediary: A bell clanged upon her heart. She felt him seize her hand: —Come! [FDS] -> there are quotation marks, but reporting clause is missing. (Leech and Short 1981, 258) Narrative Report of Speech Acts (NRSA) The possibility of a form which is more indirect than indirect speech is realised in sentences that merely report that a speech act (or number of speech acts) has occurred, but where the narrator does not have to commit himself entirely to giving the sense of what was said. (Leech and Short 1981, 259-260) He held her hand and she knew that he was speaking to her, saying something about the passage over and over again. [NRSA] -> there’s no clear information about “the passage”. Free Indirect Speech (FIS) As its name implies, FIS is normally thought of as a freer version of an ostensibly indirect form. Its most typical manifestation is one where, unlike IS, the reporting clause is omitted, but where the tense and pronoun selection are those associated with IS. (Leech and Short 1981, 260-261) He had tales of distant countries. He had started as a deck boy at a pound a month on a ship of the Allan Line going out to Canada. [FIS] -> no reporting clause. Presentation of thought A writer who decides to let us know the thoughts of a character at all, even by the mere use of thought act reporting, is inviting us to see things from that character’s point of view. As with speech presentation, the crucial factor is the semantic status of the type of thought presentation used, and the categories may be differentiated by one or more of a group of formal features. (Leech and Short 1981, 271) Presentation of thought In the presentation of speech, the use of DS or FDS produces the impression that the character is talking in our presence, with less and less authorial intervention. Similarly, in DT and FDT authorial intervention appears minimal; but as the result is effectively a monologue, with the character ‘talking’ to himself. Like the direct forms, the free indirect form takes on a different value when we turn from the presentation of speech to the presentation of thought. Instead of indicating a move towards the narrator, it signifies a movement towards the exact representation of a character’s thought as it occurs. (Leech and Short 1981, 274) Presentation of thought She had consented to go away, to leave her home. Was that wise? She tried to weigh each side of the question. [NRTA] In her home anyway she had shelter and food; she had those whom she had known all her life about her. Of course she had to work hard, both in the house and at business. What would they say of her in the stores when they found out that she had run away with a fellow? Say she was a fool perhaps; and her place would be filled up by advertisement. [FIT] Apart from the third sentence, this entire paragraph is in FIT. Eveline carries on a dialogue with herself, asking questions and trying to answer them. Presentation of thought The fact that she is questioning her decision must make us suspect that she is going to reverse it, and even here, near the beginning of the story, she seems to find more reasons for staying than for going. Throughout the story, other hints mount: Her father was becoming old lately, she noticed; he would miss her. Sometimes he could be very nice. [FIT] Conclusion In conclusion, we want to emphasise how wide is the range of options to chose from to present speeches and thoughts. “Like a hall of mirrors, each mirror capable of replicating the image in another, a discourse can embody narrators within narrations, reflectors within reflections, and so on ad infinitum.” (Leech and Short 1981, 279) In practical terms, this means that an author can potentially present the same subject from infinite viewpoints. Bibliography James Joyce. 1914. “Eveline” in Dubliners. Geoff Thompson. 1996. Voices in the Text: Discourse Perspectives on Language Reports. University of Liverpool. Leech and Short. 1981. “Speech and thought presentation” in Style in fiction. Lancaster University.