The Origins & History of the chicano movement

advertisement

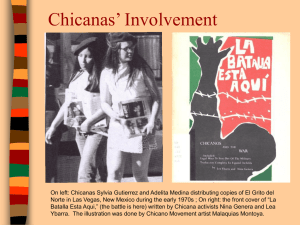

THE ORIGINS & HISTORY OF THE CHICANO MOVEMENT By: Jesus Ochoa CHICANO & CHICANA MOVEMENTS • Many mark the beginning of the Chicano movement back to when Columbus set foot on the Americas. Others mark it in the beginning at the time of the defense of Tenochtitlan and others set it at the end of the MexicanAmerican War. • The modern Chicano political movement, most people agree, began in the mid 1960’s when the struggle was both for the human/civil rights and the movement for liberation • Some of the main focal points was to raise the number of people of color to attend the universities as well as the establishment of different ethnic studies …CONTINUED • As Roberto Rodriguez explains, the best term to refer to in these situations is movement[s] because the struggles were all different with many different goals and dreams that many Chicanos envisioned. • Some of the struggles included; (PG 1) 1. To improve the lives of farm workers 2. The effort to end Jim Crow style segregation 3. The movement to improve the education system 4. The land grant struggles • Throughout time, other movements evolved that included gender equality, immigration rights, & even an access to a higher education • Most of these movements gave birth to several organizations such as Brown Berets, the Crusade for Justice, the Mexican American Youth Organization and one of the most well known one around university campuses is the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (MEChA) which, according to Ada Sosa-Riddell (director of the Chicana/Latina Center in UCDavis, ‘represents one of the long lasting legacies of the Chicano movement.’ PRECURSORS & THE MISSING GENERATION • Many of the activists from the 60’s and 70’s felt that they can make a huge difference. Lea Ybarra, a professor over at CSUFresno states that she feels like this generation takes so much for granted and “That majority of professors are more radical than the students (PG 2).” • Luis Arroyo, a professor at CSULB states that the Chicano movement began as a movement for dignity & self respect. “As time went by, we began to develop competing definitions as to what the movement was (PG 2),” he states. • To this day, those competing definitions continue to shape how many scholars and activists define what the movement was or wasn’t, when it started, when & if it ended & what it should be. • Many of the activists that participated in such events (most who were students) work with youth, in health or legal clinics or teach in schools. …CONTINUED • The main thing that differentiates the Chicano movement from Mexican civil right struggles that took place before is the is the strong student base at college campuses • The role of students in the 60’s and 70’s was unique because campuses became a political arena of war. While there had always been resistance power since the Mexican American War, it wasn’t til after WWII that Chicanos started getting noticed on college campuses. • Chicanos/Chicanas started appearing on campuses with high numbers in the 60’s. Prior absence was because there was so much segregation & discrimination in the education system • There was no eagerness in teaching the history of African Americans as well as Chicanos because after the Mexican American war, whites didn’t think it was necessary to teach the Mexican Americans …CONTINUED • Arturo Madrid, a professor at Trinity University states that there are countless untapped wealth of literature in Mexico about the Mexican-origin population in the U.S. prior to the 1960’s • Felix Gutierrez, director of the Freedom Forum’s Pacific Media Center says that “Political Activism has always been a part of the Mexican American Community. ‘What people were talking about in the 1960’s, we were living in the 1950’s,’” he says. • Gutierrez followed his parents footsteps and obtained a Master’s degree in journalism at a time when whites could obtain a job in the newsroom without degrees but as for Gutierrez, he couldn’t. He’s considered one of the nation’s top media experts • While Gutierrez sees the birth of the Chicano movement as a resurgence of the earlier 1930’s-50’s movement, he distinguishes the 1960’s as a ”period of turbulence.” LINKS TO THE BLACK CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT • Elizabeth Martinez, director of the New York chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee says that Chicano movement had not simply symbolic links with the civil rights movement but actual ties (PG 3). • Many other Chicanos were involved with the Black civil rights movement • Martinez herself grew up riding in the back of the bus which is why she has a strong bond with the civil rights movement • In ’63, after 4 little girls were killed, Martinez was enraged to the point where she joined the organization as a full-time member • In ‘66, aware of the uneasy race relations, she wrote an article titled “Neither White or Black.”. She pointed out an issue that dates back to many decades prior; when it comes down to race, Latinos don’t matter (PG 4) THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHICANO STUDIES • In later years, the struggle over access to a higher education became increasingly important. High schools, colleges and universities became the focus point of protest • UCLA professor, Juan Gomez Quinonez states that “While resistance has always been present in the Chicano community, ‘something different did happen in the 1960’s that wasn’t there before. It was an attitude.’” (PG 4) • • Prior to the Chicano movement, many people of Mexican-origin privately spoke of the Southwest as a Mexican land but it wasn’t until after the civil rights movement, it was spoken out in public ‘When Chicano studies was created, its purpose was to give intellectual support to the movement and to listen to the voices of both men and women & the community organizations …CONTINUED • Chicano studies was created, its purpose was to give intellectual support to the movement & to listen to the voices of both men and woman & the community organizations. • “Prior to the development of Chicano studies as a discipline, very little knowledge existed about the Chicano” says Refugio Rochin (PG 4). Neither was there a Chicano studies curriculum & very few Chicano professors • With the rising of ethnic studies, for the very first time, Chicanos & Chicanas began to gain knowledge about their community • “It also connected Chicanos to their indigenous roots & Native American studies & changed the way we viewed the land we lived in,” Rochin adds (PG 5) • Rochin also states that there were very few Chicano research centers throughout the Midwest because most were developed in California where Chicanos were numerous • Rochin also states that multiculturalism has actually “killed interest in Chicano studies” • Additionally, the notion of grouping all Latinos under the rubric as ‘Hispanics” has also weakened & diluted the intent of Chicano studies (PG 5) • Professors nowadays with little or no connection to Chicano studies get hired by the simple fact that they’re from Spain or South America. • “Madrid agrees that after the initial phase of Chicano studies, Chicano(a) scholarsnot by their choosing- generally confined their studies to the university (PG 5)” This is what motivated a # of scholars to create the Tomas Rivera Center in 1984 …CONTINUED • Maria Herrera Sobek, a professor at UCI is a kind of scholar that was both a product and a participant of the Chicano movement. Growing up, picking cotton, daughter of both farmed workers, attended segregated schools in Texas. Today, she is a renowned poet which her background helped her shape her academic studies. • “Chicano studies have been great for the university an d the community, however, I agrees that Chicano scholars have not been successful at presenting their research to the public. The opposition has shaped the debate (PG 6) • • • Antonio Castaneda, a history professor at the university of Texas says that Chicano Studies has challenged the structure of the university. But because it’s relatively a new field, it has historically been in a struggle for survival That’s part of the reason why many scholars didn’t engage in public police debates “The issue of housing, health, education and child warfare have not gone away,” Castaneda states. “Power will always make room for individuals.” THE RISE OF CHICANA FEMINIST SCHOLARS • Ybarra was present when the NACCS was formed. “By the time NACCS was created in 1974, women had already taken into account,” she states (PG 6). Woman had already engaged in many leadership roles around that time • The women of NACCS didn’t allow themselves to be walked upon. Despite this, NACCS did not have a conference dedicated to women until ’83 • Contrary to the belief that Mexican family promoted Chicano scholars, in which women stays at home and raise children, Mexican women have always worked at both wage and unwaged labor. “For instance, Chicano scholars have examined police brutality, but not internal violence directed at women (PG 6)” • Chicana feminists scholars are exploring issues ignored by Chicanos, such as the role of women & gender on colonial society & the early role of women in community, civil & human rights organizations. …CONTINUED • This emphasis on examining women’s issues cause a big conflict. The hugest conflict was internal- among Chicanas,” states Sosa-Riddell (PG 7) • Some of the heavy issues were issues on how to deal with lesbians. Yet, to this day, many of the same issues came intense conflict, she adds. • MALCS has allowed for a full articulation of feminism, says SosaRidell. For instance, Cynthia Orozco, visiting scholar, University of New Mexico has challenged the 1969 ‘El Plan De Santa Barbara.” the document which laid the foundation for Chicano studies as excluding women. A RESURGENCE OF THE CHICANO/CHICANA MOVEMENT • “Many scholars maintain that ever since the death of farm labor leader Cesar Chavez in ‘93, there has been a resurgence in the Chicano movement, particularly at colleges and universities nationwide (PG 7)” • This activism peaked when in ‘94, many high scholars and colleagues walked out of schools and held marches to the opposition of California’s antiimmigration proposition 187. • • Ybarra states that despite all the attacks that continue to chase Latinos and many others of color, we have to stand on our toes and be proud of who we are. She states that there is so much more to do in the future but yet again we accomplished so much within the last decades She concludes “There will always be a need for Chicano studies. It is a discipline, it’s not taught in high schools and our color’s not going to change. (PG 7)” …CONTINUED • Genevieve Aguilar, a senior at Hanks High syas that the Chicano movement is far from dead. “It lives in students like me who fight for what we still believe in today (PG 7).” She also states that she fights against those who believe that racism isn’t in the world and that there is not need for ethnic studies. • Maria Jimenez, a long-time human rights activist & director of the immigration & Law Enforcement Monitoring Project says that the proposed Latino march on Washington may be the culmination of 2530 years. She views the call as ‘A maturation of political forces.’ • From my believe, Latinos & Latinas have always had local marches because they’ve wanted to respond to the local conditions they live in • She finishes off stating that “WE’RE HERE, WE’E ALWAYS BEEN HERE & WE’RE NOT GOING AWAY!” (PG 7) CITATION • Rodriguez, Roberto, (Writer) ‘The Origins & History of the Chicano Movement,” JSRI Occasional Paper #7. The Julian Samora Research Institute, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Michigan, 1996.