Osteoporosis

advertisement

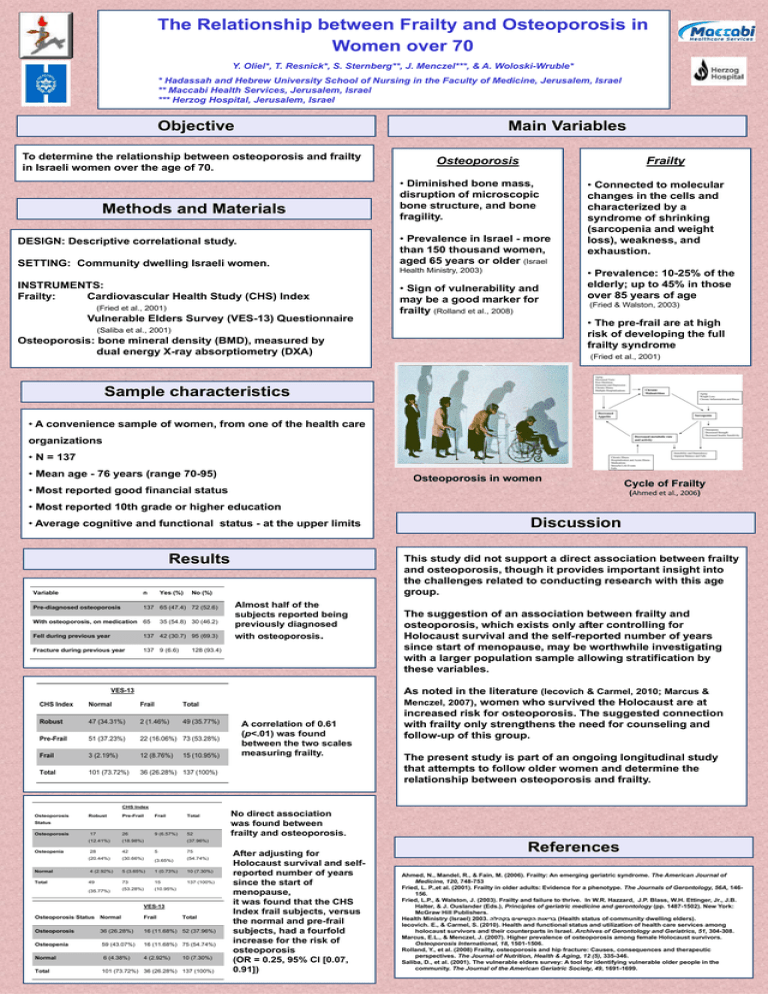

The Relationship between Frailty and Osteoporosis in Women over 70 Y. Oliel*, T. Resnick*, S. Sternberg**, J. Menczel***, & A. Woloski-Wruble* * Hadassah and Hebrew University School of Nursing in the Faculty of Medicine, Jerusalem, Israel ** Maccabi Health Services, Jerusalem, Israel *** Herzog Hospital, Jerusalem, Israel Objective Main Variables To determine the relationship between osteoporosis and frailty in Israeli women over the age of 70. Methods and Materials DESIGN: Descriptive correlational study. SETTING: Community dwelling Israeli women. INSTRUMENTS: Frailty: Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) Index (Fried et al., 2001) Vulnerable Elders Survey (VES-13) Questionnaire Osteoporosis Frailty • Diminished bone mass, disruption of microscopic bone structure, and bone fragility. • Prevalence in Israel - more than 150 thousand women, aged 65 years or older (Israel Health Ministry, 2003) • Sign of vulnerability and may be a good marker for frailty (Rolland et al., 2008) • Connected to molecular changes in the cells and characterized by a syndrome of shrinking (sarcopenia and weight loss), weakness, and exhaustion. • Prevalence: 10-25% of the elderly; up to 45% in those over 85 years of age (Fried & Walston, 2003) • The pre-frail are at high risk of developing the full frailty syndrome (Saliba et al., 2001) Osteoporosis: bone mineral density (BMD), measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) (Fried et al., 2001) Sample characteristics • A convenience sample of women, from one of the health care organizations • N = 137 • Mean age - 76 years (range 70-95) Osteoporosis in women • Most reported good financial status Cycle of Frailty (Ahmed et al., 2006) • Most reported 10th grade or higher education • Average cognitive and functional status - at the upper limits Results Variable n Yes (%) Pre-diagnosed osteoporosis 137 65 (47.4) 72 (52.6) With osteoporosis, on medication 65 This study did not support a direct association between frailty and osteoporosis, though it provides important insight into the challenges related to conducting research with this age group. No (%) 35 (54.8) 30 (46.2) Fell during previous year 137 42 (30.7) 95 (69.3) Fracture during previous year 137 9 (6.6) Almost half of the subjects reported being previously diagnosed with osteoporosis. 128 (93.4) VES-13 CHS Index Normal Frail Total Robust 47 (34.31%) 2 (1.46%) 49 (35.77%) Pre-Frail 51 (37.23%) 22 (16.06%) 73 (53.28%) Frail 3 (2.19%) 12 (8.76%) Total 101 (73.72%) 36 (26.28%) 137 (100%) 15 (10.95%) Discussion A correlation of 0.61 (p<.01) was found between the two scales measuring frailty. The suggestion of an association between frailty and osteoporosis, which exists only after controlling for Holocaust survival and the self-reported number of years since start of menopause, may be worthwhile investigating with a larger population sample allowing stratification by these variables. As noted in the literature (Iecovich & Carmel, 2010; Marcus & Menczel, 2007), women who survived the Holocaust are at increased risk for osteoporosis. The suggested connection with frailty only strengthens the need for counseling and follow-up of this group. The present study is part of an ongoing longitudinal study that attempts to follow older women and determine the relationship between osteoporosis and frailty. CHS Index Osteoporosis Robust Pre-Frail Frail Total 17 26 9 (6.57%) 52 (12.41%) (18.98%) 28 42 (20.44%) Normal Total Status Osteoporosis Osteopenia No direct association was found between frailty and osteoporosis. (37.96%) 5 75 (30.66%) (3.65%) (54.74%) 4 (2.92%) 5 (3.65%) 1 (0.73%) 10 (7.30%) 49 73 15 137 (100%) (35.77%) (53.28%) (10.95%) VES-13 Osteoporosis Status Normal Frail Total Osteoporosis 36 (26.28%) 16 (11.68%) 52 (37.96%) Osteopenia 59 (43.07%) 16 (11.68%) 75 (54.74%) Normal 6 (4.38%) 4 (2.92%) Total 101 (73.72%) 36 (26.28%) 137 (100%) 10 (7.30%) After adjusting for Holocaust survival and selfreported number of years since the start of menopause, it was found that the CHS Index frail subjects, versus the normal and pre-frail subjects, had a fourfold increase for the risk of osteoporosis (OR = 0.25, 95% CI [0.07, 0.91]) References Ahmed, N., Mandel, R., & Fain, M. (2006). Frailty: An emerging geriatric syndrome. The American Journal of Medicine, 120, 748-753 Fried, L. P.,et al. (2001). Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology, 56A, 146156. Fried, L.P., & Walston, J. (2003). Frailty and failure to thrive. In W.R. Hazzard, J.P. Blass, W.H. Ettinger, Jr., J.B. Halter, & J. Ouslander (Eds.), Principles of geriatric medicine and gerontology (pp. 1487-1502). New York: McGraw Hill Publishers. Health Ministry (Israel) 2003. ( בריאות הקשישים בקהילהHealth status of community dwelling elders). Iecovich. E., & Carmel, S. (2010). Health and functional status and utilization of health care services among holocaust survivors and their counterparts in Israel. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 51, 304-308. Marcus, E.L., & Menczel, J. (2007). Higher prevalence of osteoporosis among female Holocaust survivors. Osteoporosis International, 18, 1501-1506. Rolland, Y., et al. (2008) Frailty, osteoporosis and hip fracture: Causes, consequences and therapeutic perspectives. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 12 (5), 335-346. Saliba, D., et al. (2001). The vulnerable elders survey: A tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. The Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 49, 1691-1699.