The musket wars

advertisement

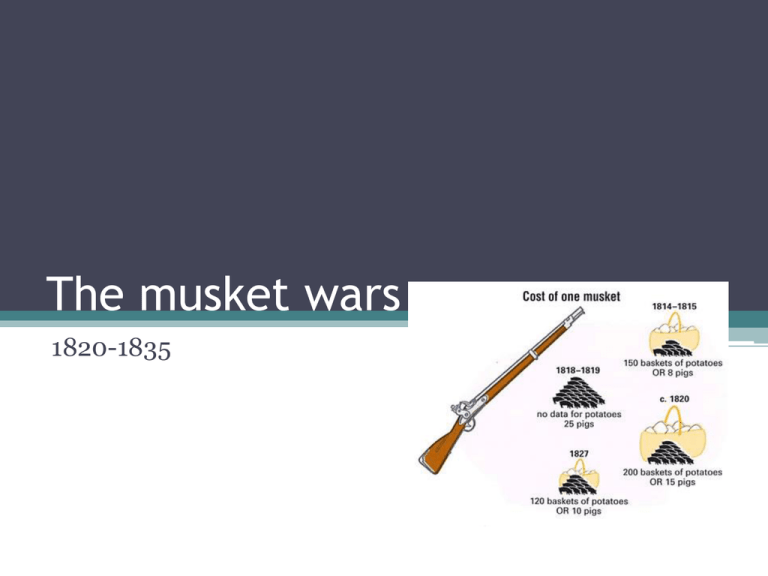

The musket wars 1820-1835 Background • With the arrival of European whaling and trading ships in the Bay of Islands, the northern tribes of Ngapuhi and their rivals the Ngati Whatua were able to trade from about 1814 on, using flax, potatoes, fruit and pigs to obtain muskets. • This led to deadly wars between the two neighbouring enemy tribes. Soon other tribes saw the necessity of obtaining muskets, and it was not long before all northern tribes were armed. Hongi Hika • Hongi Hika, uncle of Hone Heke, was quite probably the most famous of Māori warriors. He was from the Ngapuhi tribe, which traced their lineage from an ancestor "Puhi-Moana-Ariki", leading to the tribal name of Ngapuhi, Hongi Hika was master of the north and west areas to the Bay of Islands. • His date of birth is estimated at 1772, as he had told French explorers that he was born in the same year that Marion du Fresne was killed cont • When the first europeans arrived in new zealand, northern maori pronounced “h” “sh”. So hongi hika would not of immediately responded to how you read it now, it would have been shongi shika. • "Hongi" means "smell", and is also a derivative of the word "salute", representing the Māori greeting of the pressing of noses. "Hika" represents "ika", meaning "fish" in english. Hongi and Missionaries • Thomas Kendall, British missionary, established a firm and lasting friendship with Hongi Hika. As Hongi had supposedly become a converted Christian, Kendall invited him to England, with the aim of producing a Māori language bible with Hongi's assistance. • Hongi was hoping to obtain double barrelled guns and muskets for his inter-tribal wars, in particular to avenge defeats at the hands of the Ngati Whatua. cont • Hongi therefore undertook the long journey in 1820. It was not the first time that the Māori had traveled overseas. Since the arrival of European ships many Māori had, in particular, visited Australia. Hongi's tattooed and imposing appearance caused a stir in England wherever he went. • King George IV received Hongi, and donated him with a case filled with gifts in recognition of Hongi's help in introducing Christianity to the Māori people. Sydney and land sales • Hongi trades gifts from the King and land in the Hokianga (with Baron de Theirry)for muskets. • On arrival back in New Zealand with his "converted" gifts, Hongi was able to lead a number of successful raids against rival tribes, and in particular avenge previous grievances against the Ngati Whatua. Hongi continued his war party along the east coast and then into central North Island. Destruction • In 1821 he attacked the Ngati Maru tribe from the Thames area. He continued by attacking the Ngati Paoa tribe from Auckland. • A particularly violent battle was fought in 1822, when Hongi attacked the Waikato tribe, headed by Te Wherowhero, who was to be the future Māori King. The following year, Hongi attacked the Arawa tribe in Rotorua, and in the battle of Te Ika-a-ranganui in 1825 he achieved "utu" (revenge) over his defeat in 1807 at the hands of the Ngati Whatua from the Kaipara and Tamaki areas. cont • The many desperate tribes without the much-needed muskets to defend themselves soon found a way of obtaining these weapons. The European traders were more than willing to trade muskets for embalmed tattooed heads. • In war, the Māori custom was to take the heads of their victims, embalm and preserve them, and then present the heads to the family of the killed warrior. Because of the lucrative trade in dried heads, with muskets as the end goal, Māori warriors began leading skirmishes against other tribes uniquely to gain heads for ammunition. Muskets were always available, but heads began to run short, and soon the Māori found himself unable to continue supplying dried heads as previously. Fatal Impact • These wars have been described as a prime example of fatal impact theory in practice. In the wake of contact with Europeans, Māori are said to have grabbed as many guns as they could and killed as many of each other as they could. The assumption was that the introduction of European technology alone was responsible for these wars. cont • Once all tribes had muskets there were no more easy victories. Pā that had been adapted to withstand musket fire were harder to capture. By the 1830s the strain of maintaining campaigns and the impact of European diseases were taking their toll. Warfare gave way to economic rivalry. Consequence and significance • Over 20,000 maori were killed, more than what was lost in WW1 • Some of these campaigns drove tribes out of their traditional areas and into exile with relatives. Some regions were depopulated, confusing issues of ownership. When migrating iwi faced resistance from tangata whenua (local peoples), conflict spread further afield and new reasons for fighting were introduced. Its place in history • These conflicts were almost exclusively the concern of Māori, with European participation largely confined to the supply of weapons. As such they were of no great consequence to early writers seeking a grand narrative of European colonisation. • Setting aside their impact on internal Māori politics, the Musket Wars – and in particular the unease of British authorities at the participation of traders in them – contributed to the decision to colonise New Zealand in 1840. Leading to 1940 • By this time thousands of Māori had fled their traditional lands, freeing large areas for Pākehā (European) settlement and complicating questions of ownership. • Using the history resources in this room, each find a quote/opinion of an historian that could be useful in your essay. Write it up on the whiteboard.