Death of a Salesman

advertisement

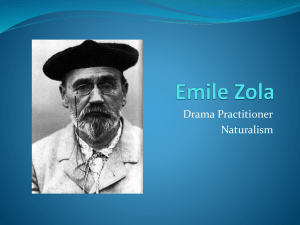

Miller's Theater the forms of modern drama Dr. Tonya Howe Marymount University March 2012 What form should a modern American tragedy take? “[I sought a form, in Death of a Salesman, that] could reflect what I had always sensed as the unbroken tissue that was man and society, a single unit rather than two.” --Miller, Timebends: An Autobiography (182) Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Realism and Naturalism Henrik Ibsen (Norwegian, 1828-1906, father of modern drama) Brought politically and socially “unsafe” subjects, like alcoholism, the hypocrisies of Victorian society, class struggle, into the theater. Realism is characterized by intense detail, scientific observation. Aesthetics/Style correlates with politics. Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Realism and Naturalism Realism and naturalism (slightly different movements, but “realism” is used to describe the basic scenic approach, where “naturalism” is used to describe a political sensibility) Darwin's evolutionary theories astonished the world in the 19th century, social movements organized around class consciousness becoming more prevalent—both challenged traditional forms of authority Theater of the 4th wall; sought to maintain an illusion of reality. But, that illusion depended also on the audience's completion of the illusion through imagination. American naturalism: Mielziner and Kazan's production of Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Realism and Naturalism Naturalism takes up the question of the position of the individual in a hostile world of social, economic, political forces. Less psychological or plot driven, more emphasis placed on class struggle in an economic system hostile to the working classes. Determinism? Individual agency? August Strindberg, Miss Julie (1888) As far as the technical side of the work is concerned I have made the experiment of abolishing the division into acts. This is because I have come to the conclusion that our capacity for illusion is disturbed by the intervals... As regards the scenery I have borrowed from impressionist paintings its asymmetry and its economy; thus, I think, strengthening the illusion. For the fact that one does not see the whole room and all the furniture leaves room for conjecture... Another much needed innovation is the abolition of footlights. This lighting from below is said to have the purpose of making the actors' faces fatter. But why, I ask, should all actors have fat faces? August Strindberg, Miss Julie (1888) [The] judgement of authors—this man is stupid, that one brutal, this jealous, that stingy and so forth— should be challenged by the naturalists who know the richness of the soul-complex and realise that vice has a reverse side very much like virtue. Because they are modern characters, living in a period of transition more feverish than its predecessor at least, I have drawn my figures vacillating, disintegrated, a blend of old and new... My souls (characters) are conglomerations of past and present stages of civilisation, bits from books and newspapers, scraps of humanity, rags and tatters of fine clothing, patched together as is the human soul. Realism and Naturalism Maxim Gorky's (1868-1936) The Lower Depths (1902), at the Moscow Art and Popular Theatre Note the intense realism, the clear focus on class struggle. The play takes place in a flop-house inhabited by criminals. Acting Contexts: Method Acting Constantin Stanislavski (Russian, Moscow Art Theater, 1863-1938) Believable emotion and realistic characters produced through physical actions; a “grammar of acting” Influenced by the systematic exploration of interiority (Freud) Acting Contexts: Method Acting Surfaces conceal a much more important well of action and emotion—emphasis is on emotional or psychological reality underlying the visible. Assumes a psycho-physical union between interior and exterior. Method actors use actions to control their emotions; actors can “live” in pauses as well as words. They react instead of acting, fully inhabiting their characters. “Staying in character.” Photographs of Death of a Salesman. Darby, Life Magazine, 1949. Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Expressionism Anti-realist movement in theater that starts in Germany in early 20th century, but spreads to America, chiefly in the work of Eugene O'Neill and Clifford Odets in the 1920s-1940s. Clearest articulation in Bertholt Brecht [1898-1956] Dismissed “Aristotelian” concepts of unity that led to theater becoming, as he saw it, about mere entertainment placating the masses. A photograph of the original set of Death of a Salesman. Darby, Life Magazine, 1949. Note the naturalism of the set; but note, too, the exposed roofline, an expressionistic influence. A sketch by Jo Mielziner for the 1949 set design of Death of a Salesman. Miller's original concept of the set was more naturalistic, but Mielziner made substantial suggestions that Miller later incorporated as the stage directions you see in the text. Note the shadows of the apartment buildings in the background. Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Expressionism Highly symbolic, expressive of interior states; also highly political and critical of bourgeois values of realism, established authority and codes of meaning Realizes this interiority, critical aspect through external scenic means: angles, dramatic lighting, sounds divorced from realistic narrative Rejected the idea that we should “enjoy” or “fall into” theater—broke the illusion of the 4th wall. Verfremdungseffekt: overt theatricality, defamiliarize the audience's expectation, alienation effect. Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Expressionism “Can we speak of money in iambics?... Petroleum resists the five-act form; today's catastrophes do not progress in a straight line but in cyclical crises... Even to dramatize a simple newspaper report one needs something much more than the dramatic technique of ...an Ibsen.” --Bertholt Brecht Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Expressionism Paul Green and Kurt Weill's Johnny Johnson (1936). Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Expressionism Eugene O'Neill (1888-1953), American expressionist. Here is a later production of his 1920s play, The Hairy Ape. Note the use of distorted perspective and destabilizing angles, intense lighting effects, stark cutouts. This seeks to evoke (or “express”) a repressive social regime. O'Neill was very radical for an American playwright, and highly controversial. Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Absurdist Theater Anti-realist movement in theater; another form of experimental theater Developed in 1950s and 1960s Like expressionism, contrary to bourgeois values of realism, established authority and codes of meaning Major themes and stylistic elements emphasized man’s reaction to a world apparently without meaning Nonsense, experimental, tragicomedy Theatrical and Scenic Contexts: Absurdism Beckett, Waiting For Godot (1955) Miller's Scenic Ideology? American theatrical context in the 1940s was generally conservative, traditional, realistic, nonpolitical, though there were experimental dramatists and directors working in the field. Miller drew both on realism and expressionism ...but rejected both in their entirety. Instead, he worked to create something new, a synthesis between them. Miller's Scenic Ideology? Untempered absurdism and expressionism represent man as nothing more than a cosmic victim, a piece of flotsam in a vast ocean over which he has absolutely no control. But untempered realism suggests that all is as it seems to be, that man can indeed master the so-harsh environment that determines his existence. In realism, cause clearly leads to effect, and realist plays take command of that narrative for social purposes. In Salesman he merges the realistic and the expressionistic. Neither wholly realistic nor wholly expressionistic, Salesman draws on both techniques to suggest social responsibility and individual agency. Miller's Scenic Ideology? Miller rejected the coldness of much expressionistic theater, and he also rejected the abstraction of expressionism, futurism, and absurdism. Yet, he also rejects a simplistically mechanistic view of the causal narrative and scenic elements of realism/naturalism, as we will see in Salesman. In strict naturalism, expressionism, and absurdism, man is wholly determined by his environment—at its mercy, we might say. He felt that theater, in order for it to be effective, needed to strike the audience with authentic emotion about man's relationship to the world he inhabits—it needs to tell a story that seeks to bring light to the unseen, hidden causes that set that story in motion. Miller's Scenic Ideology? His work, especially Death of a Salesman, is marked by stylistic experimentation. But, Instead, he insists that there be, in art, “an explicit commitment of some kind to a more humane vision of life” (Bigsby 7)--and this is the Liberal realist in him. In general, Miller's plays are concerned with the fate of the individual in a mechanistic and inhumane, even potentially totalitarian, system. But, he does not overwhelm or elide the individual with the impossibility of the system. Man is not a “cosmic victim” (11), but a failed agent; he is essentially flawed, paralyzed by deference to authority, unable to “become the protagonist of one's own drama” (10-11). Liberalism and the Humane Tragedy of the Common Man For Miller's characters there is always possible an image of a better future. His heroes are common people facing the reality of social inequity, and yet they can assert control over their fate—they are not, or should not be, controlled by it, as in the Greek drama that so influenced him. The tragedy of his characters is that they are primarily observers, not actors in their own stories—they are “unwilling, often through guilt, sometimes through fear, to intervene on their own behalf or to acknowledge their responsibility toward others” (3-4). His plays seek to show something important to the audience—to help them see, remember, and overcome. Art and the Elevation of the Everyday While Miller was writing in 1949, he was responding to a cultural moment not unlike our own. Art has a “special responsibility” in the wake of trauma. Miller's investment in the individual and the humane is evident in his stylistic choices. What is the role of art in a world that has witnessed—or forgotten—the Holocaust? That has witnessed—or forgotten— World War II? The crushing, daily experience of poverty? What is the role of art in a world that has witnessed—and not yet forgotten—Neda Agha Soltan's murder, or the selfimmolation of Mohamed Bouazizi? For Miller—and for humankind in general, perhaps—it must express the “fundamental community of mutually dependent individuals” (Bigsby 5). Art and the Elevation of the Everyday “[I sought a form, in Death of a Salesman, that] could reflect what I had always sensed as the unbroken tissue that was man and society, a single unit rather than two.” --Miller, Timebends: A Life (182) Reading Assignment: Re-read Act I of Death of a Salesman Read “Tragedy and the Common Man” Thank you!