powerpoint

advertisement

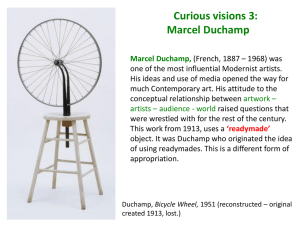

Multi media/conceptual art When did conceptual art happen? • It’s still happening! But it started mainly in the mid 1960s until the mid 1970s. It was and is an international art practice, occurring in most parts of the globe. It is still alive today, but it is always changing and being defined through the way in which artists develop the concepts and practice of conceptual art. • For many artists, teaching and making art is one and the same thing. In developing a dialogue with people, the artist is creating a social form of art. The German artist Joseph Beuys is a notable example of this principle. Some contemporary artists give public talks or lectures as their art form. Some contemporary artists set up their events in public places such as street markets or car boot sales; there is no single definition of where art can occur. History: Shock Tactics! Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917, © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2002 Marcel Duchamp – Fountain • • • • • In 1916 in New York there was an annual exhibition organised by the Society of Independent Artists. There was to be no jury, no censorship and each artist had to pay six dollars to enter a piece of work. Marcel Duchamp entered a urinal he had bought in a showroom; he had signed it ‘R Mutt’ and titled it ‘Fountain’. It was rejected from the exhibition. The debate (which has been going on since 1917) has proved more important than the object. In a period of crisis of authority (World War I) Duchamp was challenging the very basis of art and culture. Duchamp wrote that with his Fountain, ‘Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.’ Fountain is an example of what Duchamp called a 'readymade', an ordinary manufactured object designated by the artist as a work of art. It epitomises the assault on convention and good taste for which he and the Dada movement are best known. Duchamp's readymades also asserted the principle that what is art is defined by the artist. There are some very important points here: first, that the choice of object is itself a creative act. Secondly, that by cancelling the 'useful' function of an object it becomes art. Thirdly, that the presentation and addition of a title to the object have given it 'a new thought', a new meaning. Fourthly, that by signing the work the artist lays claim to it as an artwork made by him. Duchamp was an influential figure in Dada and Surrealism, an important influence on pop art, environments, assemblage, installation art, conceptual art and much art of the 1990s such as YBA or Young British Artists. Me, myself and I Gilbert and George, A Portrait of the Artists as Young Men, 1970 © Gilbert and George A portrait of the Artists as Young Men (1970) by Gilbert and George • The image shown on this slide is A portrait of the Artists as Young Men (1970) by Gilbert and George. • Gilbert and George’s art is a form of self-portraiture, since they always feature in their own work. They see no separation between their activities as artists and their everyday existence. In 1969, they began to present themselves as ‘living sculptures’ and developed the mask-like personas that are presented here. Art and Language Jenny Holzer, Truisms, 1984 © Jenny Holzer Truisms (1984) by Jenny Holzer. • The image shown on this slide is Truisms (1984) by Jenny Holzer. • In the late 1970s, Jenny Holzer wrote nearly 300 aphorisms or slogans that appeared in the public arena on stickers, T shirts, posters and electronic displays. The slogans are a form of wordplay upon commonly held truths and clichés. Initially, the Truisms were infiltrated into the public arena via stickers, T-shirts and posters. In 1982 when Holzer started using electronic displays, she blazed these messages across a giant advertising hoarding in Times Square, New York. The Truisms are deliberately challenging, presenting a spectrum of often-contradictory opinions. Holzer hoped they would sharpen people's awareness of the 'usual baloney they are fed' in daily life. • Other phrases on the artwork pictured on this slide include: • money creates taste …..most people are not fit to rule themselves ….noise can be • hostile …..old friends are better left in the past …many sacrifices. What Do You Think Now? Martin Creed, Work No. 232: the Whole World + the Work = the Whole World, 2000 © Martin Creed • • • • Martin Creed thought up this statement: the whole world + the work = the whole world He decided to make it as a very big neon sign. Tate Britain said that Martin Creed could put it on the front of the gallery for the whole world to see – and think about! • It works like an equation. What does it mean? Kendell Geers and K.O. Lab: T/Error, B/Order and D/Anger, 2003 Kendell Geers and K.O. Lab: T/Error, B/Order and D/Anger, 2003 / Neon signs / 250 x 40 x 14 cm each / Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London. Installation view: Migros Museum fur Gegenwartkunst, Zurich Kendell Geers BELIEVE 2001 Kendell Geers “BE/LIE/VE” 7 Deadly Sins, 2006 • • • • • Kendell Geers ambiguity opens up contemplation of new meanings subverting or challenging social concepts Kendell Geers’ work has examined the proliferation of violence in the mass media and how images of violence have become banalised through media-centric methods of representation. Often his work references political issues, racial politics and violence in South Africa, his country of origin. Geers appropriates and edits information from a wide variety of sources: from history, literature and religion to media and film in order to challenge or subvert existing readings and enable new ones. Art as Process Simon Starling, Shedboatshed installation view, 2005 © Tate 2005, courtesy of Simon Starling Shedboatshed (2005) by Simon Starling. • Shedboatshed (2005) by Simon Starling. • This is definitely a sculptural object – but HOW is came into being is just as important as WHAT it is. There is a concept or a conceptually driven process. • For his work Shedboatshed (Mobile Architecture No 2) 2005, Starling dismantled a shed and turned it into a boat. Loaded with the remains of the shed, the boat was paddled down the Rhine to a museum in Basel, where he dismantled the boat and re-made it into a shed. The artist describes his work as "the physical manifestation of a thought process". • Paul Shepheard on Simon Starling “One of the interesting things about this Shedboatshed is that the thing you’re looking at isn’t the whole work. Now this is always true in conceptual art generally because conceptual art uses its artwork to illustrate some other idea. I think what’s interesting about Simon’s work is that he doesn’t deal in concepts so much as actions - so the work is evidence of action having taken place which is slightly different”. Damian Hirst • • The Physical Impossibility of Death, 1991 "Mr. Hirst often aims to fry the mind (and misses more than he hits), but he does so by setting up direct, often visceral experiences, of which the shark remains the most outstanding. In keeping with the piece’s title, the shark is simultaneously life and death incarnate in a way you don’t quite grasp until you see it, suspended and silent, in its tank. It gives the innately demonic urge to live a demonic, deathlike form." • • For the Love of God by Damien Hirst) Damien Hirst's latest artwork is this life-size platinum skull encrusted with 8,601 fine diamonds. The sculpture, titled "For The Love of God," will likely sell for as much as $100 million, making it the priciest contemporary artwork ever made. White Cube gallery is selling several limited edition silkscreen prints of the work, priced from £900 to £10,000, for one sprinkled with diamond dust. The title of the piece comes from Hirst's mother who asked her son, “For the love of God, what are you going to do next?” From the New York Times: • Jim Riswold, Make Believe Damien Hirst For The Love Of God, 2007 Kendell Geers Twilight of the idols Kendell Geers Kode-X, 2003 Chevron wrapped objects, industrial steel shelving, concrete, broken glass Kendell Geers, Twilight of the idols, 2002, Found object and Chevron tape Courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and Galleria Continua, San Gimignano and Beijing Wim Botha Wim Botha Mieliepap Pietá 2004 maize meal, epoxy resin Mirrored replica, life-size Botha's use of a dietary staple to represent a religious icon in the Mieliepap Maria acts as a metaphor for the spiritual sustenance that faith offers." Wim Botha Commune: suspension of disbelief, 2001 Carved Bibles, Biblical Text, Surveillance Equipment Installation Dimensions Variable, Figure Life-size "Botha has a knack of disguising quite radical content under the veil of traditional form. " "Paper, inexpensive as it is, gains value and power as a carrier of information, • Kathryn Smith once commented that Wim Botha's work is concerned with "familiar icons and objects that speak about belief, faith, observation, transgression and forgiveness." When asked about this assessment, Wim Botha agreed, tentatively. "There are numerous, varied and sometimes conflicting aspects to my work, usually intended but definitely also spontaneously emerging." One such emerging tendency is the subtle humour and wry sense for the ironic that often (but not always) masks the essential gravity of his work. • Using the familiar, the everyday, the iconic, Wim Botha has succeeded in creating works characterised by their delicate blending of inter-acting themes. "My works are a process of distillations," the artist explains. "They attempt to reduce all-encompassing ideas and universal factors down to their core idea." Exploring along the way "intercepting variables" and "patterns", his work also offers viewers a curious glance at "the things people do, need, construct to make sense of things," be they grandiose and religious, or decorative and facile in a not so innocent fashion. • • • • • WIM BOTHA "In my work there is seldom a distinction to be drawn between the prominence of the concept and that of the medium. I work with materials central to mass consumerist applications, that are subsequently transformed in essence and meaning to a point at which material and concept becomes integrally interdependent. The works take the form of sculptural installations. I appropriate well-known, sometimes trite and over-saturated subject matter which, coupled with traditional shaping and technological elements, become the nucleus of a series of references around the inherent implication of the subject. • • The figure hangs in front of a collection of cheesy pieced-together puzzles of sunsets with a carved banner, like those bearing the motto in a coat of arms, framing the installation. Clearly playing on visual and verbal puns, this work not only interrogates the integrity and reverence of sacrifice and its often dangerous centrality to religious dogma, it also implies through its title the very human bastardisation of religious and mythical characters that often allows for very real violence. From the crusades to Heaven's Gate to suicide bombers, the devil has only made you do it as frequently as your god. Botha's Mieliepap Pietá, which was originally shown in the cathedral of St John the Divine in New York last year, is an exact mirrored image of Michelangelo's revered piece, cast here in a maize meal-based resin. Like Abraham and Isaac, it uses reversal as a tool for inciting awareness, a major, but potentially unnoticeable difference in a work that begins to undermine notions of authenticity, power and importance in relation not only to the religious and mythical narratives Botha portrays, but also the corresponding narratives of art history. In placing his mieliepap sculpture on scaffolding and through his continuous exposure of the exhibition's hanging mechanisms, the artist highlights the contrived structure of religion, art history or a standardized morality.