The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified

advertisement

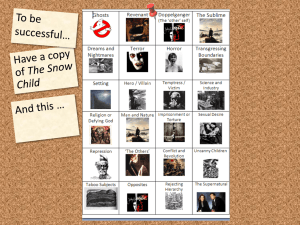

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner 2 Outline • • • • Justified Sinner and the uncanny The said and the unsaid in literary texts Gothic terror beyond the Romantic era The interest of James Hogg today JS and the uncanny • JH arguably a writer who is interesting because rather than in spite of his contradictions • . . . i.e. both non-realist and middle-of-theroad • Beyond this, perhaps the haunting power of this curiously contradictory work of fiction known as JS comes from its presentation of the uncanny JS and the uncanny • ‘Uncanny’ a word that comes from the traditions of Scottish folklore – see Gil-Martin described as ‘uncanny’ in JS, p. 186 – used to refer to persons that appear mischievous or untrustworthy and to objects that appear supernatural or strange • . . . subsequently popularized in psychoanalysis and related forms of textual analysis through Sigmund Freud’s essay ‘The “Uncanny”’ (1919) JS and the uncanny • Freud’s ‘The “Uncanny”’ – a detailed account of phenomena typically referred to as ‘uncanny’ • Thus, ‘uncanniness’ is often manifested in terms of a) the appearance of the ‘double’ b) the activity of making the inanimate animate and c) the activity more generally of ‘making strange’ JS and the uncanny • The above key components of the uncanny are already figured within the text of JS. For example . . . • The figure of the ‘double’ – doubling of the Colwans and the Wringhims; Gil-Martin’s ability to double as virtually anyone he likes; JS a curiously doubled text: the Editor’s narrative + the Confessions proper JS and the uncanny • Making the inanimate animate: George Colwan brought back from the dead through being doubled by Gil-Martin • ‘Making strange’: all the inexplicable events recounted by Robert Wringhim, reported by him while he is under the devil’s influence – or, ‘I was a being incomprehensible to myself’, as Robert himself says at one point (p. 182) JS and the uncanny • In sum, JS comes to us as a powerful evocation of the uncanny, done almost a hundred years prior to the Freudian formalization of ‘the “uncanny”’ • The above a way of describing the peculiarly haunting quality of JS as a Scottish novel of the earlier 19C The said and the unsaid in literary texts • The haunting uncanniness of JS is realized in terms of both the said and the unsaid about JH’s text • The ‘said’ and the ‘unsaid’ represent a further instance of the uncanny doubling of literary texts – silence acts as the radical otherness that shapes the text • Macherey: ‘[I]n order to say anything, there are other things which must not be said’ The said and the unsaid in literary texts • See, for example, CR: Thady Quirk (‘honest’, ‘loyal’) never has a bad word for the Rackrent dynasty – it is the silences that are doing the speaking in his damning Rackrent chronicle • MP: colonialism revealed as the price to be paid for the country house way of life through the absence of discussion – the ‘dead silence’ – of the slavery issue in JA’s novel The said and the unsaid in literary texts • W: Only passing reference to ‘the affair of Culloden’ during Edward and Rose’s wedding nuptials discloses an ‘unspeakable’ English lack of moderation at the end of the Jacobite uprising • F: Victor Frankenstein’s speechlessness of horror at what he has done in his laboratory becomes the pretext for the ‘return’ of Elizabeth into his affective life The said and the unsaid in literary texts • And JS . . .? • JH makes Robert Wringhim speak the diabolical presumptuousness of the Calvinist idea of the elect in the course of his private memoirs and confessions as a ‘justified’ sinner • JS: ‘I beheld a young man of a mysterious appearance coming towards me . . . [this was] the beginning of a series of adventures which has puzzled myself, and will puzzle the world when I am no more in it’ (p. 116) The said and the unsaid in literary texts • Robert’s confessions (the said) are a confession about what practically goes without saying (the unsaid) in JH’s novel, namely that Gil-Martin is the devil • The terrifying nature of the devil (Satan as shapeshifter) in JS is suggested in terms of the idea that his domain is that of the unsaid: he is always there in what goes without saying The said and the unsaid in literary texts • The above represents JH’s way of making the force of evil as present as possible in his fiction • JH thus turns the paradox of what is absent is present because it is absent • Turning the world upside down like this, along the axis of ‘the said’ and ‘the unsaid’, is arguably the strongest source of terror for a rationalist consciousness in JH’s novel The said and the unsaid in literary texts • No wonder this is an ‘uncouth’, ‘unpleasant’ work – ‘extraordinary trash’ – without ‘one single attribute of a good and useful book’! Gothic terror beyond the Romantic era • Realism and nineteenth-century fiction – a story of realism’s hegemonic triumph • What then becomes of the Gothic as realism’s Other? • Gothicism duly persists as the haunting ‘bad dream’ of realist consciousness and of bourgeois culture Gothic terror beyond the Romantic era • . . . as the ‘unsaid’ that goes without saying in the realist ‘said’ • . . . as the uncanny double of realism itself, always threatening as such realism’s position of dominance through a symbolic return of the repressed • See, for example, Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848) Gothic terror beyond the Romantic era • KM & FE: ‘A spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of Communism’ (Selected Works, p. 35) • KM & FE: ‘Modern bourgeois society . . . is like the sorcerer, who is no longer able to control the powers of the nether world whom he has called up by his spells’ (p. 40) • . . . here, for bourgeois vs proletarian read realism vs Gothicism (see further Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx (1994)) Gothic terror beyond the Romantic era • Bram Stoker, Dracula (1897): the vampire the figure who has no ‘spectre’ (reflection or shadow), and thus is unrepressed – has no superego – thereby allowing Lucy Westenra, e.g., to live out others’ bourgeois sexual fantasies • Compare Roger Hough, dir., Twins of Evil (1971) – a ‘post-Victorian’ or ‘modernist’ Gothic • (Vampires – whether ‘pre-’ or ‘post-Victorian’ – are never a pain in the neck (!), since their ‘bite’ brings about a sexual awakening . . .) Gothic terror beyond the Romantic era • Angela ‘We live in Gothic times’ Carter, The Bloody Chamber (1979): a collection of short stories presenting a return of the repressed of the ‘adult’ (violent, sexual) sub-texts of children’s fairy tales • . . . from the Brothers Grimm to Carter represents a movement from the ‘Romantic’ to the ‘postmodern’ Gothic • (Compare the Gothic’s return of the repressed regarding the ‘undead’, in the following postmodern novel: Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies – ‘It is a truth universally acknowledged that a zombie in possession of brains must be in want of more brains.’) Gothic terror beyond the Romantic era • See also Al-Qaeda in the ‘war on terror’ (George W. Bush, 2003) – the language of the ‘war on terror’ implies a replay of the pre-existing struggle of realist orthodoxy vs Gothic terror • Faisal Devji, ‘Al-Qaeda, Spectre of Globalisation’, Soundings, 32 (2006): ‘[Al-Qaeda] functions as the dark side of America’s own democracy, as inseparable from it as its evil twin’ (p. 27) • . . . note the suggestion of Al-Qaeda as America’s uncanny double in a ‘clash of fundamentalisms’ Gothic terror beyond the Romantic era • Thus, realism and Gothicism exist in a dialectical relationship with one another • What always makes the Gothic appear threatening to realism is its appearance as the uncanny double of realism itself • The ‘uncanny’ names the haunting power of the Gothic’s threat to realism in their ongoing ‘class’ struggle, their genre war The interest of James Hogg today • JH as a novelist remains interesting, arguably, because rather than in spite of his contradictions • The non-realist in him allows the uncanny to find an extraordinarily potent expression of itself through the idea of a devil, a Satanic shapeshifter, who is always there in what goes without saying, and is made all the more present by being absent and ‘unsaid’ • Thus, the Satanic Gil-Martin is easily a more frightening prospect than, say, the familiar stage or pantomime devil of the 19C The interest of James Hogg today • At the same time, JH appears ‘middle-ofthe-road’ in terms of his portrayal of sympathetic characters – e.g. the George Colwans – as ordinary, fallible, conciliatory • See George Colwan after his weddingnight row with his wife, Rabina: ‘for my part, I fear I have behaved very ill; and I must endeavour to make amends’ (p. 7) The interest of James Hogg today • The Editor, taking sides with George against Rabina in this particular dispute, says: ‘against the cant of the bigot or the hypocrite, no reasoning can aught avail’ (p. 5) • JS appears a novel that throws its weight behind the cause of good sense against bigotry and hypocrisy, especially within Calvinist doctrine The interest of James Hogg today • Here, the Calvinist ‘saved’ as well as the ‘damned’ implies a form of fanaticism or extremism that JH determines to speak against with his novel • Thus, JS now seems precisely the sort of text that speaks to present-day forms of fanaticism and extremism • Somewhat in spite of itself, the novel makes us see the attractions involved in going to extremes (thereby going over into the Gothic’s uncanny doubling of reality), even as it asserts a code of moderation as heroic The interest of James Hogg today • For JS read against the fanaticism of a mid-20C totalitarian age (Nazism, Stalinism, etc.) – see André Gide’s ‘Introduction’ to a 1947 French translation of JH’s text • . . . the text is read as a post-war cautionary tale about the evils of extremism: a realist antipathy to extremism finds its voice in Gide The interest of James Hogg today • A new age of fanaticism appears in the late 20C/ early 21C: Islamic Jihad (‘holy war’, as opposed to ‘spiritual struggle’), September 11th and after, the West’s ‘war on terror’, a ‘clash of fundamentalisms’ . . . • Thus, JS as an anti-extremist novel – Wringhim’s confessions become a confession of his evil – comes to speak directly to our own times The interest of James Hogg today • What does it say in this regard? • It advocates a policy of making amends instead of making war • Here, the dialectic of realism and the Gothic is resolved in such a way as to expose the terrible sameness of opposing sides within today’s new age of war The interest of James Hogg today • As Devji has suggested, an ‘equivalence of terror’ appears ‘the only form in which the two [Al-Qaeda and America] might come together and even communicate with one another’ (p. 27) • In sum, all please form an orderly queue for the asylum!