beaded collar poster... - The University of Arizona Campus Repository

advertisement

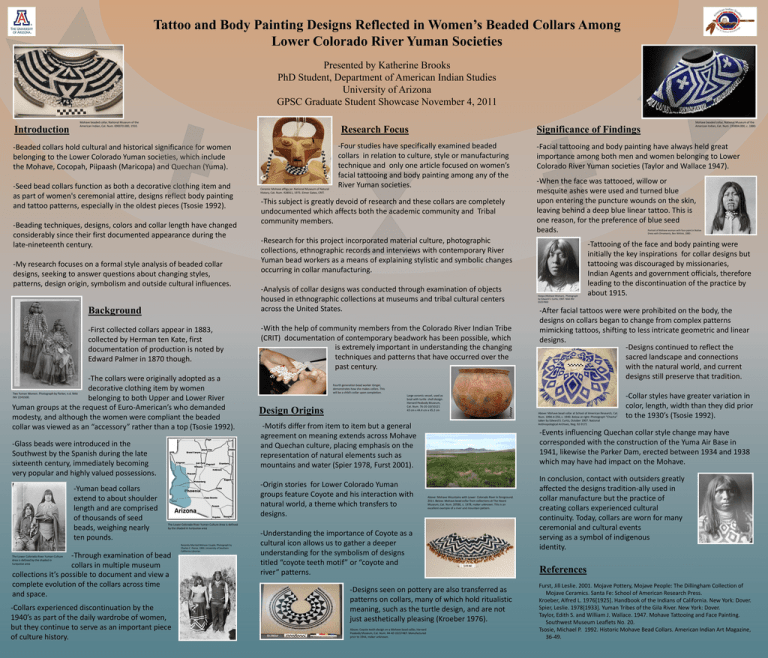

Tattoo and Body Painting Designs Reflected in Women’s Beaded Collars Among Lower Colorado River Yuman Societies Presented by Katherine Brooks PhD Student, Department of American Indian Studies University of Arizona GPSC Graduate Student Showcase November 4, 2011 Mohave beaded collar, National Museum of the American Indian, Cat. Num. 090070.000, 1910. Introduction Research Focus -Beaded collars hold cultural and historical significance for women belonging to the Lower Colorado Yuman societies, which include the Mohave, Cocopah, Piipaash (Maricopa) and Quechan (Yuma). -Seed bead collars function as both a decorative clothing item and as part of women's ceremonial attire, designs reflect body painting and tattoo patterns, especially in the oldest pieces (Tsosie 1992). -Beading techniques, designs, colors and collar length have changed considerably since their first documented appearance during the late-nineteenth century. -My research focuses on a formal style analysis of beaded collar designs, seeking to answer questions about changing styles, patterns, design origin, symbolism and outside cultural influences. Background -First collected collars appear in 1883, collected by Herman ten Kate, first documentation of production is noted by Edward Palmer in 1870 though. -The collars were originally adopted as a decorative clothing item by women belonging to both Upper and Lower River Yuman groups at the request of Euro-American’s who demanded modesty, and although the women were compliant the beaded collar was viewed as an “accessory” rather than a top (Tsosie 1992). Ceramic Mohave effigy jar. National Museum of Natural History, Cat. Num. 428911, 1975. Elmer Gates, CRIT. -Yuman bead collars extend to about shoulder length and are comprised of thousands of seed beads, weighing nearly ten pounds. -Four studies have specifically examined beaded collars in relation to culture, style or manufacturing technique and only one article focused on women’s facial tattooing and body painting among any of the River Yuman societies. -Through examination of bead collars in multiple museum collections it’s possible to document and view a complete evolution of the collars across time and space. The Lower Colorado River Yuman Culture Area is defined by the shaded in turquoise area -Collars experienced discontinuation by the 1940’s as part of the daily wardrobe of women, but they continue to serve as an important piece of culture history. Recently Married Mohave Couple, Photograph by Charles C. Pierce, 1900..University of Southern California Libraries. -Facial tattooing and body painting have always held great importance among both men and women belonging to Lower Colorado River Yuman societies (Taylor and Wallace 1947). -When the face was tattooed, willow or mesquite ashes were used and turned blue upon entering the puncture wounds on the skin, leaving behind a deep blue linear tattoo. This is one reason, for the preference of blue seed beads. Portrait of Mohave woman with face paint in Native Dress with Ornaments, Ben Wittick, 1880 . -Research for this project incorporated material culture, photographic collections, ethnographic records and interviews with contemporary River Yuman bead workers as a means of explaining stylistic and symbolic changes occurring in collar manufacturing. -Analysis of collar designs was conducted through examination of objects housed in ethnographic collections at museums and tribal cultural centers across the United States. -With the help of community members from the Colorado River Indian Tribe (CRIT) documentation of contemporary beadwork has been possible, which is extremely important in understanding the changing techniques and patterns that have occurred over the past century. Heepa (Mohave Woman), Photograph by Edward S. Curtis, 1907. NAA INV 03257800 -Tattooing of the face and body painting were initially the key inspirations for collar designs but tattooing was discouraged by missionaries, Indian Agents and government officials, therefore leading to the discontinuation of the practice by about 1915. -After facial tattoos were were prohibited on the body, the designs on collars began to change from complex patterns mimicking tattoos, shifting to less intricate geometric and linear designs. -Designs continued to reflect the sacred landscape and connections with the natural world, and current designs still preserve that tradition. Fourth generation bead worker Ginger, demonstrates how she makes collars. This will be a child’s collar upon completion. Design Origins Large ceramic vessel, used as boat with turtle shell design. Harvard Peabody Museum, Cat. Num. 76-20-10/10121 43 cm x 44.4 cm x 45.2 cm Above: Mohave bead collar at School of American Research, Cat. Num. 1994-4-250, c. 1940. Below at right: Photograph “Chacha” taken by Edward S. Curtis, October 1907. National Anthropological Archives, Neg. 92-9171 -Motifs differ from item to item but a general agreement on meaning extends across Mohave and Quechan culture, placing emphasis on the representation of natural elements such as mountains and water (Spier 1978, Furst 2001). -Origin stories for Lower Colorado Yuman groups feature Coyote and his interaction with natural world, a theme which transfers to designs. The Lower Colorado River Yuman Culture Area is defined by the shaded in turquoise area Significance of Findings -This subject is greatly devoid of research and these collars are completely undocumented which affects both the academic community and Tribal community members. Two Yuman Women. Photograph by Parker, n.d. NAA INV 2245500. -Glass beads were introduced in the Southwest by the Spanish during the late sixteenth century, immediately becoming very popular and highly valued possessions. Mohave beaded collar, National Museum of the American Indian, Cat. Num. 193804.000, c. 1880. -Events influencing Quechan collar style change may have corresponded with the construction of the Yuma Air Base in 1941, likewise the Parker Dam, erected between 1934 and 1938 which may have had impact on the Mohave. Above: Mohave Mountains with Lower Colorado River in foreground. 2011. Below: Mohave bead collar from collections at The Heard Museum, Cat. Num. 205BE, c. 1978, maker unknown. This is an excellent example of a river and mountain pattern. -Understanding the importance of Coyote as a cultural icon allows us to gather a deeper understanding for the symbolism of designs titled “coyote teeth motif” or “coyote and river” patterns. -Designs seen on pottery are also transferred as patterns on collars, many of which hold ritualistic meaning, such as the turtle design, and are not just aesthetically pleasing (Kroeber 1976). Above: Coyote teeth design on a Mohave bead collar, Harvard Peabody Museum, Cat. Num. 44-40-10/27487. Manufactured prior to 1944, maker unknown. -Collar styles have greater variation in color, length, width than they did prior to the 1930’s (Tsosie 1992). In conclusion, contact with outsiders greatly affected the designs tradition-ally used in collar manufacture but the practice of creating collars experienced cultural continuity. Today, collars are worn for many ceremonial and cultural events serving as a symbol of indigenous identity. References Furst, Jill Leslie. 2001. Mojave Pottery, Mojave People: The Dillingham Collection of Mojave Ceramics. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. Kroeber, Alfred L. 1976[1925]. Handbook of the Indians of California. New York: Dover. Spier, Leslie. 1978[1933]. Yuman Tribes of the Gila River. New York: Dover. Taylor, Edith S. and William J. Wallace. 1947. Mohave Tattooing and Face Painting. Southwest Museum Leaflets No. 20. Tsosie, Michael P. 1992. Historic Mohave Bead Collars. American Indian Art Magazine, 36-49.