Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation - pams

advertisement

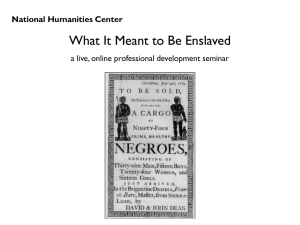

FOREVER FREE: THE STORY OF EMANCIPATION & RECONSTRUCTION IN THE UNITED STATES By Eric Foner, with illustrations edited and commentary added by Joshua Brown PART ONE. AN HISTORIOGRAPHY OF RECONSTRUCTION How Everyday Americans Understood the Reconstruction, 1865 - 1877 Public Memory of Reconstruction Instead of seeing the Reconstruction Period as a time when AfricanAmericans won greater rights, the Reconstruction is often viewed as a “punishment” against white Southerners. The “Radical” Republicans sought to grant liberty, citizenship, and voting rights to AfricanAmericans – and many Southern whites considered this vindictive... When African-Americans and a few Northern whites were elected to office – with Union guns behind them – according to the popular Southern memory – the former Confederates were outraged. Since most Southerners sought to preserve the slave system of social hierarchy after the war, the newly won freedom of former slaves was resented. Resentful Southerners hate Northerners and their agencies – like the Freedman’s Bureau – which advocated for AfricanAmerican rights in the aftermath of the Civil War. Northerners who came to the South to help the society rebuild – land speculators and financiers, yes, but also teachers, clergymen, and members of aid societies – were often viewed as selfinterested, self-righteous, and judgmental characters. They were called “Carpetbaggers” and it was commonly supposed that they had come to the South to take advantage of white Southerners during their time of need. Reconstruction Reconstruction from Southerner’s Perspective Groups like the Freedman’s Bureau, which intervened to provide food, shelter, economic aid, and job opportunities for newly free African-Americans, were portray by Southerners as meddlers who encouraged African-Americans to be lazy and rebellious. In fact, fewer than 1000 Freedman’s Bureau agents were in the South to begin with, and their primary work was to prevent black codes and homelessness from causing enormous harm to blacks in the Deep South. Because of the desire on the part of Northerners and Southerners alike to reunify the nation in the aftermath of the Civil War, it was commonly related that both sides had fought honorably for what they believed was right – and that both sides had fought valiantly for a “just cause.” This interpretation of the war simply left out the narrative of African-Americans and the role which they played in fighting and winning the war for the Union. AfricanAmerican slavery, which was the most important cause of the Civil War, was now a topic which veterans tried to avoid! The Desire to Reunite, Repair, and Reconstruct after the Civil War Film Portrayals of the Reconstruction Distort the History of the Period Film depictions of African-Americans during the Reconstruction period made African-American characters seem simple or, worse yet, unscrupulous. D.W. Griffin’s “The Birth of a Nation”, which was screened in the White House for then President Woodrow Wilson – a well-known segregationist – invents a lie about mob rule by AfricanAmericans and portrays the Ku Klux Klan (a violent hate group responsible for hundreds and perhaps thousands of murders during the period) as an agency promoting order and good will attempting to protect Southern women from assault. In “Gone with the Wind”, African-American characters are distorted as well – loyal slaves like Mammy, embittered black soldiers, evil scalawags, and punitive carpetbaggers are stock characters in the film. Both films were considered epic dramas and masterpieces when they were released. And while the films were infatuating and spectacular for audiences in their respective periods, they are surely not good history. D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” “Gone With the Wind” W.E.B. DuBois: Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880 Setting the Record Straight: The Historian W.E.B. DuBois’ publication, Black Reconstruction in America • W.E.B. DuBois – the historian – published Black Reconstruction in America in 1935, a first attempt to set the record straight. He is, of course, better known for co-founding the NAACP and his book, The Souls of Black Folk. • His book, Black Reconstruction in America is subtitled, “An essay toward a history of the part which black folk played in the attempt to reconstruct democracy in America.” • Dubois finds the Reconstruction to be a “splendid failure” showing the potential of African-Americans to create a society which celebrates virtuous goals – although undermined by the power and force of racist whites of the era. To DuBois, attempting to understand the Civil Rights struggle and the fight for the franchise was simply impossible without an understanding of the Reconstruction Period. PART II. SLAVERY IN UNITED STATES HISTORY: AN OVERVIEW The Coexistence of Slavery and Liberty in an age of Individual Liberty and Representative Government Understanding Slavery as a Part of American History • Slavery was never simply accepted, and a desire to create a just society was • • • • present in African-American communities long before the Civil War brought Emancipation and an opportunity for freedom. Even under the slave system, African-Americans found ways to exercise their freedom and to protest their condition. Slaves on the plantations slowed down their working pace, broke tools, and undermined the productivity of the plantation to protest their condition of servitude. Many slaves were allowed to work on their own plots of land during “free time.” Religious celebrations and a uniquely African American culture emerged on the plantation in this manner. Slaves in urban areas frequently were able to acquire skills and make their own money in public markets – some were able to purchase their own freedom and establish profitable businesses in the process. Just as importantly, slavery was an ever-present political issue in the United States; it was always recognized as wrong and at odds with our basic values as a representative democracy. It was in opposition to our beliefs as articulated in the Declaration of Independence. Even the Founding Fathers recoiled at the notion of slavery – leaving the word out of the Constitution despite many references to the violent system itself. George Washington and Slavery George Washington failed in many ways to articulate an antislavery stance during his lifetime. He initially refused to allow slaves and free blacks to serve in the Continental Army; he presided over the Constitutional Convention which both protected and empowered slaveholders in the South; and he OWNED slaves, which he kept even as he accepted the Presidency in 1789. The flaws of Washington are particularly manifest when it comes to the issue of slavery in America. He did, however, make provisions in his will to emancipate his slaves when his wife passed away. (She liberated them almost immediately – fearing that slaves anxious for freedom may take her life.) At Mount Vernon, George Washington held hundreds of slaves which he kept even as he assumed the Presidency in 1789. His wife eventually liberated them. Thomas Jefferson and Slavery Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, removed a passage from that document which criticized the British for maintaining slavery. He held hundreds of slaves – even as President – and had an affair with Sally Hemmings, a slave presumed to be the half-sister of his late wife Martha. Enslaved people, recognizing that the language of liberty applied to their own circumstances, used it in an effort to win their own liberty both during the Revolutionary War period and afterwards. Consider, for example, the banner reading “DEATH OR LIBERTY” which the slave Gabriel’s followers planned to carry in their failed rebellion of 1800 in Richmond, VA. Jefferson often compared the hypocrisy of slavery to “holding a wolf by its ears” – he feared maintaining slavery but also feared ending it. Slavery: A System Based Upon Violence It is often asked, “Why didn’t slaves fight back against their owners?” They did, of course. Nevertheless, we tend to associated slavery with passive, harmonious, and orderly work. Southern slave owners worked hard to maintain this image of slavery in the popular mind, and took pride in their own “paternalism.” They viewed slaves as inferiors but also as dependents and usually sought to maintain a strict hierarchy on their plantations. But ultimately, what kept slaves on the plantations doing work – what allowed plantation owners to sell children away from their mothers – what allowed overseers to whip and brutalize slaves – was violence. Every slave understood that the master could take his or her life without any practical legal consequence. Robert E. Lee – Slaveholder Defenders of slavery like Robert E. Lee contended that slaves were only suited to agricultural labor – that they were intellectually deficient, and that they were unable to acquire any great intellectual ability. Some, like Lee, claimed that by enslaving African-Americans and their ancestors Americans had benefitted the enslaved because they had thereby brought them to Christianity, or that slaves were treated better by their Southern owners than Northern industrial workers were by their bosses. But enslaved men and women had no hope for social improvement under the slave system. The race based, hereditary system of slavery meant that generations to come would remain in slavery. Part III. Slave Revolts, Uprisings, and the Polarization of the US over Slavery Nat Turner’s Rebellion wasn’t the first slave revolt. Hundreds of revolts had taken place over the years – from the Stono Rebellion and Denmark Vesey’s uprising in South Carolina to the Gabriel’s Revolt in Richmond, Virginia in the year 1800. In Haiti, a slave revolt against the French had even resulted in the an independent nation of former slaves. But Nat Turner’s revolt sent out alarm bells across the South. The Southampton Virginia exhorter had organized a massacre – killing men, women, and children – and then escaped punishment for months. When he was caught, he was hung, then skinned. Virginians briefly considered ending the slave system, but instead chose to violently punish the conspirators and then create stricter laws controlling slavery. Nat Turner’s Rebellion of 1830, Southampton, VA SECTION IV. THE ANTEBELLUM PERIOD : ENGENDERING WAR How the United States was Polarized and Provoked into War over the Issue of Enslaved Men and Women Having run on the posturing campaign motto “Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!”, a barb intended for English ears over the Oregon Country, Polk was soon embroiled in a dispute not with England, but with our neighbors to the South, in Mexico. Desiring the resource rich land of California, Polk quickly provoked a war with Mexico, defeated them, and demanded the cession of Mexico’s northwestern provinces. The Mexican Cession of 1848 included California, as well as most of the American Southwest. But the rapid expansion left Americans reeling and anxious over the future of slavery as pioneers and settlers went forth. James K. Polk, Texas, and the Mexican-American War THE COMPROMISE: California entered the Union as a free state. The slave trade was banned in Washington, D.C. Popular Sovereignty would determine the future of slavery in Western Territories. The Fugitive Slave Law was made stricter than ever, requiring Northerners to aid in the capture and return of runaway slaves from the South. The Compromise of 1850 TIMELINE: Events of the 1850s Polarize Americans over Slavery 1850 – The Compromise of 1850 left Southerners angry over the decline of their influence in the Congress – and doubtful that slavery would be extended into the West. Northerners were equally outraged that they might be compelled to participate in the capture and return, indeed, the enslavement of runaway “property.” 1852 – Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin is published, enraging Southerners for it portrayal of slaveholders and eliciting great, passionate support for abolitionism among Northern readers. 1854 – The Kansas-Nebraska Act resolves that popular sovereignty would determine the future of slavery in the west. “Bleeding Kansas” a microcosm and forerunner of the Civil War, breaks out in the Kansas Territory. John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry, VA In 1858, radical abolitionist John Brown and a handful of his followers marched into Harper’s Ferry, VA intending to provoke a slave rebellion on a massive scale. Brown was a veteran of the fighting in Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas, and had devoted his live to the destruction of slavery. He vowed to purge the land of the sin of slavery with blood, if necessary. Although the uprising in Harper’s Ferry was quickly put down, the South was nonplussed by the event. A white man had led slaves into battle, openly advocating murder, revolution, and bloodshed. And what was worse in the eyes of most Southerners, Brown was considered a hero by many Northern abolitionists, from Frederick Douglas to Ralph Waldo Emerson, to William Lloyd Garrison. Depictions of Brown as a martyr and hero were inexplicable to those who favored slavery, yet, they persisted. PART V. THE CIVIL WAR AND AFRICAN-AMERICANS EMANCIPATION How African-Americans Liberated Themselves During the Course of the United States Fratricidal War The Goal of the Union, 1861 Students of American History realize that Abraham Lincoln’s goal at the start of the Civil War was to reunify the Union. He did not seek to end slavery, and indeed, four states and the District of Columbia all allowed slavery during the course of the Civil War. When Fort Sumter was attacked, when Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to defend the nation, and even as the fighting of the war continue through 1862, the only goal Lincoln articulated was the preservation of the Union. And yet, enslaved African-Americans themselves knew that war had an more meaningful imperative. They viewed the event as a Biblical struggle for liberty. And most took steps to gain their own freedom, expediting the process. When the war began, AfricanAmericans viewed it as a war for their own liberation. Despite pronouncements to the contrary and despite an effort at the start of the conflict to return slaves to their masters in the South, blacks consistently fled to the Union lines and surrendered themselves to the US Army. By the end of 1861, Union General Benjamin Butler, stationed at Fort Monroe near Hampton, VA, began to accept African-Americans as “contraband of war.” Soon, African-Americans flocked to the encampment, worked in its barracks, and founded “contraband schools” to educate themselves. Even if the Union soldiers and government were not ready to admit it, the war would be about the emancipation of enslaved people – the slaves themselves would insist upon it! General Benjamin Butler and “Contraband” at Fortress Monroe, Hampton, VA, 1861 The Emancipation Proclamation The start of the Civil War went poorly for the Union Army, as it was dealt defeat after defeat by a better prepared Confederate military. Lincoln, as an act of military necessity, decided to liberate the slaves. He believed (1) that liberating slaves in the South would cripple the area economically, and (2) that AfricanAmericans serving in the Union Army would help the cause of the nation. And yet, even at this point, the war was not exclusively about ending slavery. Indeed, Lincoln did not free the slaves in the Union’s border states, and he did not free the slaves in parts of the South which were not actively in revolt – places, for example, like Princess Anne County, VA! The Gettysburg Address Perhaps more than any other speech, the Gettysburg Address defines the changes in the goals of the Union during the Civil War. The brief address, which was delivered on November 19, 1863 to dedicate the national cemetery on the site of the battlefield, redefined the purpose of the war. Lincoln’s speech was not well received, as it was short and the anxious crowd sought to hear more from the President. Yet, upon further review, it is treasured as part of our national creed. The “new birth of freedom” Lincoln invokes is a clear reference to the emancipation of enslaved people and the resolve to maintain our nation’s representative democracy “of the people, by the people, for the people.” The Role of African-American Soldiers in the Civil War Close to 200,000 African American soldiers fought on the side of the Union during the Civil War, and many died for the cause of liberty and the emancipation of their people. From the onset of the war, African-American leaders like Frederick Douglass had petitioned President Lincoln to allow black soldiers into combat. There had been many problems along the way. Many whites did not believe African-American soldiers could perform their duties under fire. Even when troops were enlisted, they received only 62% of the wages whites drew. Yet, they came to serve their nation and to fight for their own liberation. The most famous of the regiments to form was the 54th Massachusetts Colored Regiment, led by white abolitionist William Gould Shaw. The regiment performed dutifully along the South Carolina coast, liberating parts of the regions before meeting catastrophe at Fort Wagner on the Atlantic shoreline. The 54th Massachusetts Colored Regiment In January of 1865, General William Tecumseh Sherman responded to a group of African-American freedmen’s request for land. The group, known as the Savannah Colloquy, was symposium of leaders in the African American community who had once met with Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton regarding the future of the newly freed black population of South Carolina. They sought liberty, which they defined as the ability to inherit the fruits of their own labor. They needed land, and Sherman was willing to accommodate their request. Largely because he felt the freedmen following his army had become a bit of a burden, he promised each slave family in the South Carolina community forty acres of land – and a broken down mule from his own army. The promise was not meant to inspire anything but local change, but it was quickly vested with great power. Even to this day, Spike Lee’s Forty Acres and a Mule Filmworks celebrates the promise – the broken promise, one must remember, of Sherman’s Field Order #15. Sherman’s Field Order #15 PART VI. THE RECONSTRUCTION Conflict Between the Formerly Enslaved and the Confederate Social Hierarchy Following the Civil War The Black Codes • Most states required that African-Americans sign yearly labor contracts with local whites – and those who refused could be arrested for vagrancy. Often, the punishment for vagrancy was a fine, and if the African-American in question could not pay the fine, his labor would be auctioned off to a white landowner who could. Slavery? • Courts could declare poor families incapable of providing for their children and assign those children as unpaid laborers to local white families. • Blacks were not allowed to sit on juries in trials against white defendants. • Blacks were not allowed to move freely, work freely, or participate freely in civil society. Northerners were outraged at the Black Codes, and responded by increasing the powers and responsibilities of the Freedman’s Bureau to intervene and protect the rights of African Americans. According to Foner, “The Chicago Tribune, the leading Republican newspaper of the Midwest [declared]: ‘We tell the white men of Mississippi that the men of the North will convert the state of Mississippi into a frog pond before they will allow such laws to disgrace one foot of soil in which the bones of our soldiers sleep and over which the flag of freedom waves!” The Freedman’s Bureau Intervenes Lincoln’s Ten Percent Plan By far the most lenient of plans for Reconstruction, Abraham Lincoln’s Ten Percent Plan would never be articulated in full – for he was assassinated. The principle points of the plan, however, were clear: Once 10% of a Southern State’s population had declared loyalty to the United States, they could form a new state government and apply for re-entry into the Union. Every state must ban slavery. While most Confederate soldiers would be granted amnesty, no Confederate government leaders or top military officials could represent the state in governmental positions. Andrew Johnson was both a Democrat and a Southerner; Lincoln had picked him as Vice President in 1864 just to show his goodwill toward the Southern States. When Lincoln was murdered, Johnson was very unpopular! Radical Republican leaders in Congress did not trust him, especially after he vetoed the extension of the Freedman’s Bureau and the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Bad blood ensued, and within two years, Johnson found himself being impeached before Congress. Meanwhile, the Congress attempted to take complete control over the Reconstruction process. Andrew Johnson’s Presidential Reconstruction, “Restoration” The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson • In 1867 and 1868, the Congress accused Andrew Johnson of committing “high crimes and misdemeanors” for firing a member of his own cabinet, violating the Tenure of Office Act – a completely unconstitutional measure created just for the occasion. • In February of 1868, he was put on trial before the Senate, which came just one vote shy of removing him from office. • After 1866, however, Johnson was completely ineffective as President of the United States – Radical Republicans had taken control of both houses of Congress, and were able to pass both laws with or without his approval – simply overriding the President’s veto power when necessary. Radical Republicans in Charge, and African American Enfranchisement Radical Republicans are often portrayed as men and women eager to punish ex-Confederates. Indeed, many harbored animosity towards Southerners. More importantly, however, Radical Republicans sought equal rights under the law for the formerly enslaved African-Americans living in the South. Among the accomplishments of the Radical Republicans: The 13th Amendment, ending slavery in the United States. The 14th Amendment, providing citizenship rights for all persons born in the United States, with the exception of Native American Indians. The 15th Amendment, which provided voting rights for African American men. The establishment and continuation of the Freedman’s Bureau, which created schools and provided assistance securing jobs and basic needs for the formerly enslaved. Laws which reversed the Black Codes of the Southern States and fought against hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan, which grew to prominence in the South following the Civil War. Providing African American Suffrage was the key to success for Radical Republican leaders. Although today we consider suffrage a basic right of all American adults, at the time of Reconstruction there were large portions of the population who were considered citizens but unable to vote. Traditionally, there had been property requirements in order to vote, women had been forbidden the franchise, and states had been able to decide for themselves which citizens could participate in elections and which could not. But after the Civil War, African American leaders quickly recognized that the right to vote was essential to participation in American society as equals. As Eric Foner writes, “In a society that had made political participation a core element of freedom, the right to vote inevitably became central to the former slaves desire for empowerment and autonomy.” Abolitionist and government appointee Frederick Douglas explained it this way: “Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot!” The Fifteenth Amendment After the Civil War was the first time African Americans had been given the franchise on a wide scale, and the first time that they had been able to run for elected office. By the late 1860s, many African-American leaders ran for public office successfully, including local, state, and national offices. In the South Carolina state legislature, the majority of delegates elected to office were African-Americans, and states from South Carolina, to Mississippi, to Louisiana sent black officials to Congress. Many of these leaders were able to transform the way Americans thought about the African-American population through their efforts. Nevertheless, racism and threats were an ever-present threat for African-American leaders. African Americans are elected to office. Senator Hiram Revels (R) Mississippi Senator Hiram Revels had been born a free man in North Carolina and traveled around the United States quite a bit during his lifetime. His most prestigious job before the Civil War had been as a schoolmaster in Baltimore, MD. But after the Civil War, he joined the Freedman’s Bureau, which brought him to Mississippi. From there, he rose to social prominence. As many newspapers and historians have noted since, Revels, when sworn into office in 1870, took the seat once vacated by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Senator Blanche K. Bruce (R) Mississippi Blanche K. Bruce had been born as a slave near Farmville, Virginia – perhaps the son of his owner. He had been privileged as a slave, allowed to learn how to read and write by a tutor in the family who also worked with his half-brother. He had left his master at the start of the Civil War and become a school teacher in Samuel Clements (Pseudonym: Mark Twain) hometown of Hannibal, Missouri. From there, he moved to Mississippi, where he invested in a plantation, and worked as a tax collector for Bolivar County. He rose to prominence through diligence and hard work, and was elected to the United States Senate in 1875. Eric Foner describes Robert Smalls: “In May of 1862, in one of the Civil War’s most celebrated acts of individual daring and bravery, Robert Smalls, the slave pilot of the Confederate navel vessel the Planter, brought on board his family and several other slaves, disguised himself as the captain, guided the ship out of the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, and surrendered it to Union forces. The feat won for Smalls an officer’s commission in the Union navy and a reward of $1500, which he later used to purchase land in Beaufort, South Carolina, his place of birth. During Reconstruction, Smalls would become one of the most powerful political leaders of the state. He served five terms in Congress in the 1870s and 1880s, and as late as 1913 he held the position of collector of customs in Beaufort. Only when President Woodrow Wilson swept most of the remaining black appointees from office did Small’s long political career come to an end.” Congressional Representative Robert Smalls, (R) South Carolina President Ulysses S. Grant, 1869 - 1877 • Although often condemned as a poor manager of his own • • • • government and a corrupt leader, Ulysses S. Grant was very devoted to the cause of freedom and the preservation of the Union’s established goals. Grant’s Administration suffered from corruption, particularly corruption related to the rapidly expanding railroads, but his devotion to equal rights under the law for the formerly enslaved never wavered. Under Grant, soldiers continued to occupy the South, the Freedman’s Bureau continued to advocate for the formerly enslaved, and laws were passed to prevent domestic terrorism by groups like the Ku Klux Klan. The 15th Amendment was passed while Grant was President. The Transcontinental Railroad was completed under the leadership of President Ulysses S. Grant, as well. PART VII. A SUMMARY VIEW OF THE RECONSTRUCTION Alternatives, Perspectives, Compromise, Abandonment, and the Failed Legacy of the Reconstruction Unfortunately, conditions among poor people in the South did not improve economically as quickly as many had supposed they would. The United States government refused to simply give away land to the formerly enslaved – or to poor whites for that matter. Most of the plantation in the South were not immediately profitable, and having to pay labor costs in a post-slavery economy undermined their profitability. And thus, the sharecropping system emerged. Poor farmers would work the land of a larger plantation owner, and pay rent for their living arrangements by handing over a portion of their crop to the owner. Generally, the tenant farmer (sharecropper) was never able to pay off their rent, pay for their tools and satisfy their basic needs without falling into debt – and the cycle of poverty continued. Sharecropping and Poverty Faced with a lack of economic opportunity in the South, and confronted with the arbitrary danger of hate groups like the Ku Klux Klan, many AfricanAmericans chose to emigrate from the region. For some, organized pilgrimages towards Caribbean or African destinations were pursued. But many other African Americans set forth towards the West. They called themselves ‘Exodusters’ – invoking the images of Old Testament Israelites – who escaped slavery(The Pharaoh V. the Confederacy) , crossed a great body of water (Red Sea V. Mississippi River), and sought to sustain themselves in a desert-like region (Land of Canaan V. Kansas)by hard work and steadfast faith in God. “Exodusters” Many African-American men decided to join the United States military, a choice which was difficult given the open racism and discrimination which thrived in that organization. Some black soldiers were stationed in the South during the Reconstruction, but more were sent to points West, where they were employed in forts along the Frontier. Clearing the railroads, maintaining telegraph wires, and protecting settlers – often by fighting against Native Americans – were their principle duties. The irony that black soldiers would risk life and limb to fight against Native Americans for the benefit of white settlers who discriminated against and, indeed, oppressed both groups has been much written about. Bob Marley’s famous song, “Buffalo Soldier” address the topic as well. Buffalo Soldiers The Accomplishments of African American Leaders During Reconstruction • Legal gains passed through national and state governments which • • • • ended slavery, provided citizenship rights, and granted the franchise to black men were all articulated – even if they were denied regionally in the South. An imperfect wage system had been established for AfricanAmerican works, and land ownership had been achieved by close to one in seven of the formerly enslaved. Black Churches were organized and became the center of many new communities. The Freedman’s Bureau schools organized by African-Americans inspired the public school system (for both whites and blacks) across the entire South. Although these schools were segregated, in most places, they were the first of schools to be established at all. African American men participated in government as both voters and elected officials. The Compromise of 1877 • In 1876, the Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes and the Democratic candidate Samuel Tilden were in a bitter contest characterized by violence on both sides. • While Tilden had won more popular votes in the election, the Electoral College votes needed for victory were not secured by either man. • Disputed election returns in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida forced Congress to investigate the issue. • The Compromise, or Bargain of 1877 resulted from this inquiry. The Compromise of 1877 The corrupt bargain that was struck in 1877 resulted in Rutherford Hayes becoming President of the United States. Not every aspect of the agreement came to fruition, but the basics of the agreement did. Rutherford B. Hayes would become President of the United States. Republicans in Congress promised not to intervene in the affairs of Southern States, and to allow Democrats to claim control of the local governments in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. Rutherford B. Hayes promised to appoint one Southerner to his Presidential Cabinet. Hayes also promised to provide federal aid to the Texas and Pacific Railroad, which was creating a Southern Railroad route across the West. Finally, Democrats promised to respect the civil and political rights of African American citizens. Southern State Undermine the Voting Rights of African-Americans Southern states almost immediately resumed the practice of creating black codes to control the movements and economic opportunities of African-American citizens. Voting restrictions were established as well, preventing African-American men from exercising the franchise: Literacy Tests and Poll Taxes prevented many AfricanAmericans from being eligible to vote. Grandfather clauses allowed white citizens to vote – even if they were illiterate or poor – as long as someone in their families had previously voted. (Most enslaved persons had no one in their “legitimate” families who had ever cast a ballot.) The Practice of Lynching and Violence continues… Mobs of angry whites would take the law into their own hands whenever African-American men were accused of crimes in the South. Since black men were not allowed to testify against whites in court, and because most of the high ranking members of society – judges, police officers, teachers, and sometimes even ministers – participated in the crimes, lynch mobs were generally fearless of the law. Often, people who had just committed heinous crimes against humanity would stop to have their portraits made by the murdered person. In doing so, their own dignity was the worst corrupted. This practice continued well into the 1960s, although some very courageous individuals – starting with Ida B. Wells-Barnett and continuing across history to men like Booker T. Washington and Medgar Evers, spoke out bravely against the practice. “Jim Crow” Law Segregate the South “Jim Crow” was a character in a popular minstrel routine practiced during the mid to late 19th Century – a comedy routine where white actors would paint their faces black and then act like buffoons and dance wildly to ridicule African Americans. “Jim Crow” laws, though, were used to segregate the South and to prevent any sort of public interaction between blacks and whites – in schools, restaurants, public parks, transportation systems, and even bathrooms. The Segregated South created by Jim Crow laws was obviously discriminatory, yet, it was maintained as “social custom” by white Southerners for nearly a century. Plessy V. Ferguson, (1896) In the 1896 Supreme Court Case of Plessy V. Ferguson, Homer Plessy sued a commuter train company for violating his rights by refusing to allow him to sit in a first class seat alongside white customers. The Supreme Court ruled that segregation was legal in public facilities, so long as the institutions were “separate but equal.” This case would be used to justify segregation and racist practices for the next 58 years, before being overturned in Brown V. Board of Education, Topeka, KS, in 1954. A barrier on the gains made by African-Americans during the Civil War and Reconstruction had been established which would persist until a second Civil Rights Movement emerged a half century later. W.E.B. DuBois on Reconstruction • Eric Foner, in Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction, argues that many white Southern historians of the early 20th Century considered the Reconstruction a “tragic era” of misrule and tyranny. • Yet, “For DuBois, the tragedy was not that Reconstruction was attempted, but that it failed. DuBois called it a “splendid failure,” since the era demonstrated the capacity of African-Americans for the full enjoyment of citizen’s rights. And, in the families, schools, and churches created or consolidated after the Civil War, and in the constitutional amendments that established the principle of legal and political equality regardless of race, Reconstruction laid the foundation for future struggle.” • One truly cannot understand the power of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s without a proper understanding of the Reconstruction Era. Moreover, the Civil Rights Movement of the 20th Century could not have achieved its successes without the foundation which was constructed by African-Americans in the years following the Civil War. BASED ON THE BOOK FOREVER FREE: THE STORY OF EMANCIPATION AND RECONSTRUCTION, BY ERIC FONER Illustration edited and with commentary by Joshua Brown