ENGL_427W_Presentation_Angela_Lamb_Jessi_Chai

advertisement

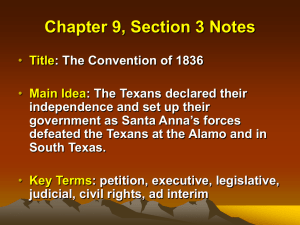

Anna Yearsley: A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave Trade (1788) Presentation by: Angela Lamb & Jessi Chai Table of Contents • • • • • • • • • Definitions Biography & Background Poetic Success: A Fresh Start – Hannah More: Anna’a First Patron Social Response to Yearsley and More’s Feud Anna & The Bluestocking Circle “Portraits in the Characters of the Nine Muses in the Temple of Apollo” by Samuel Johnson Yearsley’s Publications Situating A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave Trade (1788) within Historical Context Triangular Trade”: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Route – • • • • • Map, Ship Diagram & Advertisements Yearsley’s Concerns Frederick Augustus Hervey – The Dedication Summary of the Poem Unifying “Mankind”: Domestic Sentiment Yearsley’s Portrayal of “Mankind” • • • • • • Key Moments Themes Literary Similarities – “Oroonoko”- Aphra Behn – Inkle and Yarico Discussion Questions Pop Quiz Works Cited Definitions Inhumanity: “The quality of being inhuman or inhumane; want of human feeling and compassion; brutality, barbarous cruelty.” (OED Online) Slave-Trade: “Traffic in slaves; spec. the former transportation of black Africans to America. “ (OED Online) Biography & Background • Anna Yearsley (née Chromartie) was born in 1756, on the outskirts of Bristol, England at Clifton Hill. • She was born to “laboring class parents;” consequently, she did not attend school and was not provided with a formal education. • Anna’s mother was a milk-woman; nothing is known about her father. • Anna was apprenticed by her mother as a milkmaid, and was nicknamed by the community as “Lactilla,” and “the Bristol Milk- woman.” • Anna was taught to read by her brother, William. Their mother oftentimes brought home books for them to read that were loaned to her by the “people whom she delivered milk to.” • Some of the books Anna read throughout adolescence include Milton’s “Paradise Lost” and “Night Thoughts” She was also familiar with some of Shakespeare’s plays. • Anna got married at the age of 18 to John Yearsley—he was a yeoman farmer. She and her husband had seven children– five boys and two girls. • After ten years of marriage, the family became impoverished and destitute. • By 1784, John “lost [his] yeoman status and was described as [a] ‘labourer’ in a deed of trust intended to protect his wife's earnings.” • Records from this time indicate that the Yearsley’s had “five children”– two of her sons died. • Landless and starving, the Yearsley family “lived” in barn during the winter months. Tragically, starvation claimed Anna’s mother’s life and she died while huddling for warmth in the barn. • Soon after, their family was “rescued” by a man by the name of Mr. Vaughn, and his charitable organization. Poetic Success: A Fresh Start • Following the family’s rescue, Anna met (and was hired by) Hannah More in September 1784. • Hannah More was an “esteemed Christian moralist, poet, [philanthropist] and educator.” She took immediate notice of Ann’s natural “literary talent and arranged for her work to be published by subscription.” • The publication was a huge success; however, the relationship between More and Yearsley crumbled. More felt that she was owed greater monetary compensation for her assistance and felt Anna was “ungrateful” to her. They never fully reconciled-- Anna was focused on “maintain[ing] full editorial control of her work,” and believed that all the money earned from her poetry was hers alone to keep. • Anna continued her literary career without More’s involvement . In addition to her poetry collections, she also published some novels and a play. In 1793 she “opened a borrowing library in Bristol.” • Ultimately, Anna Yearsley “was one of only a few working-class women of the era” to be published. In 1803 her husband died– upon his death she “retired to Melksham in Wiltshire,” where she eventually died in 1806. • Upon her death, the local newspapers in Bristol “reported […] that [she was] a prominent, worthy person.” According to Bristol bookseller and literary patron Joseph Cottle stated in 1837 that he “remembered [Anna] as evincing, ‘even in her countenance, the unequivocal marks of genius’.” Hannah More: Anna’s First Patron • Part of the first generation of romantic writers along with Mary Wollstonecraft, Ann Radcliffe, Anna Letitia Barbauld, and many more (1790s-1800s) • Renowned abolitionist and actively encouraged women to join the anti-slavery movement. • Integral member of the Bluestocking group. • Conflicts involving class, jealousy, and appropriate financial restitution are what caused the dissolution of Yearsley and More’s relationship. Social Response to Yearsley and More’s Feud “Two Sappho’s in one City bred & born, Sufficient a Whole Kingdom to adorn. Tis hard to say, which we must more admire, More’s polish’d Muse, or Yearsley’s Muse of Fire. Yearsley self taught uncramp’d by Art or Rhyme, Is forcible pathetic & Sublime;But More’s trim Muse subdues the Critic’s Heart, And leads it Captive by the Rules of Art.” -Eliza Dawson Anna & The Bluestocking Circle • Anna became a member of the Bluestocking circle (initially through Hannah More’s invitation). This group was comprised of intelligent, intellectual women in Britain during the 18th century who advocated on behalf of educational and social reform– they are considered to be one of the first feminist groups. • The Bluestocking’s were advocates of the abolishment of slavery and were concerned with “emphasiz[ing] education and mutual co-operation rather than […] individualism.” • Notable members include Anna Letitia Barbauld, Hannah More, Samuel Johnson and Edmund Burke. • The Bluestocking’s supported the “intellectual endeavors” and projects of each member (reading, artwork, and writing), and like Yearsley, many were published writers. The group placed paramount importance on “intellectual enjoyment;” ultimately, they opposed the “universal tyranny of a custom (gambling and playing cards) which absorbed the life and leisure of the rich,” and were focused on discussing “literature and the arts.” • Men were also members of the Bluestockings-- although the group was founded by women, they seemed to collectively encourage gender neutrality and equality in the pursuit of intellectual development. “Portraits in the Characters of the Nine Muses in the Temple of Apollo” by Samuel Johnson • Johnson-- a renowned painter-depicted the nine, most prominent members of the Bluestockings as the Nine Muses. • Although Yearsley is not included in this portrait, Anna Letitia Barbauld is pictured (behind the easel), along with Hannah More (centre). Yearsley’s Publications • First volume- Poems on Several Occasions (1785). Anna is assisted by Hannah More--she invested her time and supplied financial aid to help Anna publish the work (More organized a subscription service with her wealthy group of friends and peers). – These poems explored “religious and domestic themes.” • Second volume- Poems on Various Subjects (1787). Anna receives help and encouragement from the Earl of Bristol (Frederick Hervey) to publish her collection– he provides her with financial aid. “A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave Trade” is held within this collection. – Hannah More is no longer involved with any of Ann’s writing/publishing. • Third volume- The Rural Lyre: A Volume of Poems (1796). Situating A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave Trade (1788) within Historical Context • Bristol: Rooted in the slave trade, dating back to the 11th century. The trade revolved around capturing Anglo-Saxon men, women and children and selling them off to locations “throughout the world.” Their enslavement was eventually “forbidden by the crown.” • 17th century: The British Empire began to colonize the Americas and the Caribbean-slavery became “an increasingly important commodity.” • Bristol gained financial prosperity because of the slave trade. Bristol, the West Indies and Africa comprised “the three points of the slave triangle.” • 1697-1807: approximately 2,100 trips were carried out upon Bristol’s slave ship “The Beginning” for transporting African slaves. • Start of the 18th century, abolitionist literature began circulating and its production increased during the 1770-80’s. The literature helped to incite “political and economic resistance on part of the British middle and upper class” while exposing “the evils of slavery.” • In 1787, the “Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade” was founded, and by 1788 they were publishing and circulating the majority of abolitionist propaganda. 1807the Slave Trade Act abolished slavery in the British Empire; however, it was not until 1833 that slavery was finally rendered an illegal practice. “Triangular Trade”: The Transatlantic Slave Trade Route • “Must our wants/Find their supply in murder?” (26) • “The sweet luxuriant cane” (16) • “Slave ships carried goods (cloth, guns, ironware and drink) that were traded in exchange for slaves, at the West African coast.” • Bristol’s first slave ship was named “The Beginning.” • Slave traders either captured people OR purchased them from African chiefs. • “Money made from the sale of the enslaved Africans, supplied Britain with goods (sugar, coffee and tobacco) that were bought and carried back to Britain for sale. “ The Slave Ship: “Cargo Planning” Slaves For Sale: 18th Century Advertisements Yearsley’s Concerns • Anna Yearsley (and fellow abolitionists, like Hannah More) began “campaigning against slavery;” ultimately, Yearsley et. al., helped form the “Committee for the Abolishment of the Slave Trade” in May, 1787. • Yearsley’s poem represents an act of agency on behalf of the marginalized and oppressed– she suggests that by understanding others’ suffering as our own, we will act more compassionately to one another. Furthermore, she argues for the development of “social love,” and that society must redefine its “self-interest.” • The poem depicts “extended portraits of suffering” for the enslaved and the fundamental point of the poem is that society must collectively favor “social love” because it is the sole “universal good.” The poem expresses her passionate plea for society to turn away from the slave trade and instead, favor humanity. • The poem also functions as a MAJOR critique of commerce by connecting the idea of one’s “home” with the “domestication of suffering.” Yearsley makes it clear that the desire to make money and be profitable is causing society to behaviour “injurious[ly]” to people. • Yearsley calls into question the legitimacy of contemporary custom with regard to the treatment of slaves within the context of “commerce” versus “domesticity.” Yearsley’s life experience as a labouring, lower-class woman allows her to express her concerns with the system of commerce in Bristol. Frederick Augustus Hervey The Dedication: Frederick, Earl of Bristol • Frederick is Yearsley’s patron (sponsor) for her second collection of poetry-- he provided her with significant financial aid to help publish the work. • The dedication provides us with information that indicates Yearsley is attempting to arouse compassion by “aligning her sense of power, with her imaginative representation of him.” • For example, Yearsley writes “Vanity is flattered, when I but fancy that Your Lordship feels as I do.” Anna seems to “invert their economic relationship” and is essentially trying to appeal to his senses through praise, in hopes that he will enact more substantial forms of social advocacy. • Moreover, Anna implies that by adopting and nurturing a sense of powerful compassion, the Earl will read the poem correctly. She posits the notion that power can be both “powerful and powerless” and suggests that the former is more authentic and effective. Powerful compassion (within a social and political context) nurtures one’s conscious choice to act with agency. Ultimately, powerful compassion is Anna’s solution for challenging inhumanity– she contrasts the relationship between the commodification of humanity, with the concept of “social love.” Summary of Poem • Yearsley claims that “Custom […] hast undone us,” and has “led us far / From God-like probity, from truth, and heaven” (3). • Society does not adhere to what is true and morally right– we do not adhere to the purest ideals or the highest principles. Instead, we behave injuriously and favor the commodification of mankind to profit financially. • Society is the “slave of avarice” and are disconnected from human suffering. Again, we are consumed with the insatiable desire to obtain wealth through greediness (4). • The poem shames colonialism, imperialism, slavery, commerce, etc. and questions the legitimacy of its so-called “Christian” foundation. • Slavery disallows people from maintaining their “Heav’n-born Liberty”—for e.g. experiencing sacred moments with family is denied (Death of a parent pg. 5-6). Summary- continued • • • • • • “Bristol, thine heart hath throbb’d to glory. Slaves […]” (1) Yearsley is addressing the problems of the commodification of mankind in the very first line of the poem. • Bristol-- where Anna was born is now a city flourishing because of the inhumanity and sinful nature of the slave trade. “We feel enslaved” (2) • Who is “we?” The slaves? Women? Children? The poor, working class? “Horrid and insupportable” (4) – Slavery is worse then death (see Luco’s attempt at escape in Key Moment slide.) “My song / Shall teach sad Philomel a louder note, When Nature swells her woe” – Referencing Philomela – A character in Greek mythology – Raped by her sister’s husband, Tereus; has her tongue cut off to be silenced forever. She becomes a nightingale. • Anna writes that her “song” will encourage the “Philomel” (nightingale) to sing more loudly. Yearsley wants her poem to inspire hope and faith in those who are marginalized & oppressed within the confines of society. Yearsley criticizes the English law-- how can we place ownership over another person’s life? – “Speak, ye few / Who fill Britannia’s senate, and are deem’d / The fathers of your country! Boast you laws, / Defend the honour of a land so fall’m” (27) – Reference to “Rule Britannia Rule” Summary- continued -Christianity & Religion• • • • • • “* Indians have been often heard to say, in their complaining moments, “God Almighty no love us well; he be good to buckera; he bid buckera burn us; he no burn buckera.” Yearsley asks “[…] where/ Is your true essence of religion? where /Your proofs of righteousness, when ye conceal/The knowledge of the Deity from those/ who would adore him fervently? Your God/Ye rob of worshippers, his altars keep/Unhail’d, while driving from the sacred font/The eager slave, lest he should hope in Jesus.” (22) On page 23, Yearsley describes how the Turks give freedom to their slaves if they embrace “Mahometism.” “* Spaniard, immediately on purchasing an Indian, gives him baptism” Towards the end of the poem Yearsley advises “Advance, ye Christians, and oppose my strain” (25). “A fellow-creature’s blood: bid Commerce plead/ Her publick good, her nation’s many wants” (26). Summary- continued “Indian Luco” & his lover, Incilanda: – Luco is captured by Christian slaver traders; he is “destin’d to plant/The sweet luxuriant cane.” (16) – Yearsley describes how the labor is wearing out his body. – Slave masters whip him. – Yearsley goes on to describe Luco’s greatness and Incilanda’s undying love for her man. They used to meet at noon, but Luco is not there. She mourns as she is “banish’d from his arms,” (14) – Burned to death Unifying “Mankind”: Domestic Sentiment Yearsley’s Portrayal of “Mankind” White Men • • • • • • • • • “guileful crocodile’s” (3) “slave[s] of avarice” (4) “seller of mankind” (7) “Selfish” and Remorseless Christian” (8 & 18) “superior […] boast[ful]” (8-9) “Christian renegade” and “violate[s] justice” (16) “cruel soul” (17) Prideful and malicious (18) Inhumane Slaves (Luco) • “gentle” (9) • “generous breast” and “faithful lover” (10) • Loving and devoted to his beloved, Incilanda (10) • “strives to please, / nor once complains” (16) • “smothers grief” (16) • “poor Indian, with the sage, is prov’d / The work of a Creator” (13) Key Moments • “[…] where / Is your true essence of religion? Where / Your proofs of righteousness […]. / Ye hypocrites, disown / The Christian name, nor shame its cause: yet where / Shall souls like yours find welcome?” (22) • “[…] Oh, social love, / Thou universal good, thou that canst fill / The vacuum of immensity, and live / In endless void! / […] touch the soul of man; / Subdue him; make him a fellow-creature’s woe / His own by heart-felt sympathy, whilst wealth / Is made subservient to his soft disease.” (29-30) “By nature fierce; while Luco sought the beach, / And Plung’d beneath the wave; but near him lay / A planter’s barge, whose seamen grasp’d his hair / Dragging to life a wretch who wish’d to die.” (19) Themes • Slaves = commodity – Torture (20 & 21) • Slaves = women no equality, freedom, etc. – “Sight no more / Is Luco’s, his parch’d tongue is ever mute” (21). Literally and figuratively silenced. – Philomela symbolic representation of both the “slave,” and those in society who are held under the thumb of social hierarchy. • Religion • “Social love” • Souls (“Nature”) Literary Similarities • “Oroonoko” by Aphra Behn (1688): Similar fate as Luco: punished for striking his master; facial features altered permanently. Burned to death. • “Inkle and Yarico” (1787): comic opera & first staged in London • “A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave Trade” by Anna Yearsley (1788) • “Slavery: A Poem” by Hannah More (1788) Discussion Questions 1. What do you think Anna’s motives were for writing this poem? Is this truly an act of advocacy to encourage and influence social change, or was she merely trying to profit off of the “slave trade.” Is Luco a literary commodity? 2. By taking Yearsley and More’s feud into account, and recognizing that they each published pro-abolitionist poetry in 1788, do you feel that their poems were influenced by their conflicts (and or “competition”)? If so, how does this influence our impression of the poem? 3. Do you feel that Yearsley was justified in distancing herself from More? Was Anna’s decision founded upon an “ungrateful disposition,” or was it ultimately a testament of Ann’s strong-willed nature (to preserve her own personal autonomy)? POP QUIZ 1. What was Anna’s maiden name? a) Chromartie b) Hervey c) Lactilla 3. Anna had ___ children and her husband was a ____ farmer. a) 7 , cattle b) 5 , cattle c) 7 , yeoman 2. Which volume of poetry contained “A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave Trade,” and what year was it published? a) Poems on Several Occasions (1785) b) Poems on Various Subjects (1788) c) Poems on Various Subjects (1785) 4. Anna was given a/an ____ education and her brother’s name was _____. a) formal , John b) informal , John c) informal, William d) formal , William WORKS CITED “Ann Yearsley (1752-1806).” Poetry Foundation. Poetry Foundation, n.p. Web. 22 Jan. 2013. http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/ann-yearsley “Brilliant Women: the Bluestocking Circle.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, n.p. Web. 22 Jan. 2013. http://www.oxforddnb.com/public/bluestockings/ “Bristol’s Role in the Slave Trade and Abolition.” Bristol. Britain Online, 2013. Web. 27 Jan. 2013. http://www.bristol.org.uk/history/slave_trade/ Felsenstein, Frank. “Ann Yearsley and the Politics of Patronage The Thorp Archive: Part 1.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 21.2 (2002): 346-392. Print. Ferguson, Moira. “The Unpublished Poems of Ann Yearsley.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 12.1 (1993): 13-29. Print. Mitchell, Robert Edward. “The soul that dreams it shares the power it feels so well”: The Politics of Sympathy in the Abolitionist Verse of Williams and Yearsley.” The Transatlantic Poetess 23.30 (2003): n.p. Web. 22 Jan. 2013. http://www.erudit.org/revue/RON/2003/v/n29/007719ar.html Waldren, Mary. “Ann Yearsley.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press, 2004. Web. 29 Jan. 2013. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/30206 Yearsley, Ann. “A Poem on the Inhumanity of the Slave-Trade.” BrycchanCarey. 17 Nov. 2007. London: G.G.J. and J. Robinson, 1788. n.p. Web. 20 Jan. 2013. http://www.brycchancarey.com/slavery/yearsley1.htm Photos: Ann Yearsley [photo]. Retrieved January 22, 2013, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Ann-Yearsley.jpg Ann Yearsley [photo]. Retrieved January 22, 2013, from: http://www.oxforddnb.com/templates/article.jsp?articleid=30206&back= Bluestockings Muse Portrait [photo]. Retrieved January 29, 2013, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Portraits_in_the_Characters_of_the_Muses_in_the_ Temple_of_Apollo_by_Richard_Samuel.jpg Bristol Slave Ship [photo]. Retrieved January 29, 2012, from: http://www.flickr.com/photos/brizzlebornandbred/5130645895/ The Dedication [photo]. Retrieved January 22, 2013, from: http://discoveringbristol.org.uk/browse/slavery/P2410/ Frederick August Hervey [photo]. Retrieved January 22, 2013, from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Hervey,_4th_Earl_of_Bristol Hannah More [photo]. Retrieved January 27, 2013, from: http://www.awesomestories.com/assets/hannah-more “Luco is gone” [photo]. Taken by Jessi Chai from actual Yearsley poem: January 31, 2013. Map of Slave Trade Route [photo]. Retrieved January 27, 2013, from: http://www.africanculturalcenter.org/4_5slavery.html “Negroes for Sale” Advertisement [photo]. Retrieved January 29, 2013, from: http://www.bbc.co.uk/suffolk/content/articles/2007/03/08/suffolk_and_the_sla ve_trade_feature.shtml “To Be Sold” Slave Advertisement [photo]. Retrieved January 27, 2013, from: http://african-american-rights811.blogspot.ca/2008/03/why-till-case-stillmatters.html