Anglo-Saxon & Old English History and Literature

advertisement

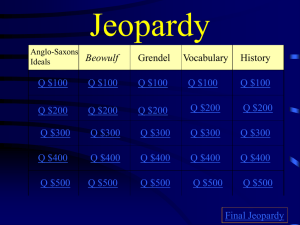

Overview of Periods of Early English History Pre-History—1066 A. D. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Pre-Rome/Pre-History up to 55 B. C. Roman Occupation 55 B. C. – 410 A. D. Anglo-Saxon Period 410 – 787 A. D. Viking Invasions 787 – 1066 A. D. Norman Conquest begins in 1066 Pre-Historic / Pre-Roman ??-55 B.C. Stonehenge circa 3100 BC A towering circle of ancient stones, draped in the mist of centuries. The clatter of horses’ hooves, the clash of swords and spears. A tiny island whose motley tongue would become the language of the world, and whose laws, customs, and literature would help form Western civilization. This is England, and the story begins here. McDougal Littell, p 18 The islands we know as Great Britain have been occupied by man since the Paleolithic Period [Old Stone Age]. We have archeological evidence dating back 40,000 years of nomadic peoples living in what is now England and Wales. © Dane Degenhardt, Monde Dane, 2009. www.wordinfo.info/.../Eng-hist-2-Celts-Brit.gif Centuries of Invasion The Dark Ages, as the Anglo-Saxon period is often called, was a time of bloody conflicts, ignorance, violence, and barbarism. Life was difficult, and the literature of the period reflects that reality. Little imagery of the brief English summers appears in this literature; winter prevails, and spring comes slowly, if at all. The people were serious minded, and the reader finds scarce humor in their literature. Indeed, many of the stories and poems present heroic struggles in which only the strong survive. And no wonder. McDougal Littell, p 19 Chief among the earliest actual cultures was a group of loosely related tribes called Celts which inhabited most of central Europe. It is not known when the Celts entered Great Britain; but according to Julius Caesar, it was likely before 200 BC. The Celtic tribe which entered Great Britain was called the Brythons [which became Britons from which we get the term Britain]. The Celts were great story-tellers, great drinkers and great fighters - with a liking for single combat, after which the victor proudly displays the severed head of his opponent. Their religion was polytheistic [from the Greek roots polys-many; theos-god]. The Celts in Europe began to trouble their very different neighbors, the sober and disciplined Romans during the first century B.C. http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.asp?groupid =831&HistoryID=aa84&gtrack=pthc#ixzz0ukMiW6rF The first person ever to write about England may have been the Roman general Julius Caesar, who in 55 B.C attempted to conquer the British Isles. Put off by fierce Celtic warriors, Caesar hastily claimed victory for Rome and returned to Europe, leaving the Britons (as the people were known) and their neighbors to the north and west, the Picts and Gaels, in peace. McDougal Littell, p 19 Fosse Way- Built in 47 AD by the Emperor Claudius , it is the only road remaining from the initial Roman invasion. geograph.org.uk A century later, however, the Roman army returned in force and made good Caesar’s claim. Britain became a province of the great Roman Empire, and the Romans introduced cities, roads, written scholarship, and eventually Christianity to the island. Their rule lasted more than three hundred years. “Romanized” Britons adapted to an urban lifestyle, living in villas and frequenting public baths, and came to depend on the Roman military for protection. Then, early in the fifth century, the Romans pulled out of Britain, called home to help defend their beleaguered empire against hordes of invaders. With no central government or army, it was not long before Britain, too, became a target for invasion. McDougal Littell, p 19 www.hadrians.com/.../roman_soldiers_clothes.html Summary of the Roman Occupation Julius Caesar began the invasion/occupation of Britain in 55 B.C. His visits planted the seeds for trade and diplomacy that made possible the later occupation by Claudius. Tacitus, Agricola 13 The occupation was completed by the Emperor Claudius from 43 to 50 A.D. The Romans left in 410 A.D. because the Visigoths attacked Rome and the fall of the empire began. By 476 there was no longer a western Roman Empire. St. Augustine landed in Kent in 597 and converted King Aethelbert (king of Kent, the oldest Saxon settlement) to Christianity; he became the first Archbishop of Canterbury. Roman architecture found in England today. Hadrian’s Wall built about 122 A.D. Roman baths at Bath, England www.travelpod.com/.../tpod.html www.travlang.com www.english-heritage.org.uk/.../ Cultural and Historical Results of the Roman Occupation in Britain Military Infrastructure The Romans built a strong government (fell apart when the Romans left). Architectural structures were built: Roads, walls, cities, villas, public baths (some remains still exist) Language and Writing Celts were pushed into Wales and Ireland. Romans prevented Vikings from raiding for several hundred years: C. Warren Hollister writes, “Rome’s greatest gift to Britain was peace” (15). Latin became the official language The practice of recording history led to the earliest English “literature” being documentary [Venerable Bede 672-735: Ecclesiastical History of the English People]. Religion Christianity began to take hold, especially after St. Augustine converted King Aethelbert www.classjump.com/.../Anglo-Saxon%20%20Old%20English%20History%20and%20Literature%201.ppt The Most Important Results of the Roman Occupation Latin heavily influenced the English language. Relative peace prevailed. Christianity began to take hold in England (but did not fully displace Paganism for several hundred years). The Anglo-Saxon Period 410-787 www.classjump.com The Angles and Saxons, along with other Germanic tribes, began arriving from northern Europe around 449 AD. The Britons—perhaps led by a Celtic chieftain named Arthur (likely the genesis of the legendary King Arthur of myth and folklore)—fought a series of battles against the invaders. Eventually, however, the Britons were driven to The west (Cornwall and Wales), the north (Scotland), and across the English Channel to an area of France that became known as Brittany. McDougal Littell, p 19 McDougal Littell, p 19 http://www.phancocks.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/lo calhistory/germanic.htm Settled by the Anglo-Saxons, the main part of Britain took on a new name: Angle-land, or England. Anglo-Saxon culture became the basis For English culture, and their gutteral, vigorous language became the spoken language of the people, the language now known as Old English. Important Events in the Anglo-Saxon Period From 410- 450, Angles and Saxons invaded from Baltic shores of Germany, and the Jutes invaded from the Jutland peninsula in Denmark. [The Geats, a tribe from Jutland, appear in the epic Beowulf.] Nine Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms eventually became the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy (England was not unified), or “Seven Sovereign Kingdoms.” www.classjump.com Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy [hept=7 arch=government, rule] Heptarchy = Seven Kingdoms [England-to-be] 1. Kent 2. Essex (East Saxon) 3. Sussex (South Saxon) 4. East Anglia 5. Northumbria 6. Mercia 7. Wessex (West Saxon) Scotland-to-be 5 6 4 Wales-to-be 2 1 7 3 Do you recognize any of these names? www.classjump.com Viking Invasions 787-1066 home.online.no/~joeolavl/viking/osebergskipet.htm McDougall-Littell, p 20 The first Viking raids in the British Isles were in 793. For the next 30-40 years, the Vikings engaged in hitand-run raids where they landed a small number of ships at a settlement, spent a few days pillaging and burning it before heading back to Scandanavia to sell their booty. The Vikings were after two types of booty - riches and slaves - which they carried off to sell. They soon found that the monasteries were the richest sources of both goods and this is why monasteries suffered so much. However, the Vikings also attacked a lot of grád Fhéne (commoner's) dwellings. getasword.com/.../ www.wesleyjohnston.com/.../vikings.html www.wesleyjohnston.com/.../vikings.html Picture by Ray Pritchard PicturesOfEngland.com McDougall-Littell, p 20 A sidebar about the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. http://www.britannia.com/history/ docs/asintro2.html The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is one of the most important documents that has come down to us from the middle ages. It was originally compiled on the orders of King Alfred the Great in approximately A.D. 890, and subsequently maintained and added to by generations of anonymous scribes until the middle of the 12th Century. The original language was AngloSaxon (Old English), but later entries were probably made in an early form of Middle English. We like to think of this document as the ultimate timeline of British history from its beginnings up to the end of the reign of King Stephen in 1154. The Chronicle certainly does not present us with a complete history of those times and is probably not 100% accurate, either, but that doesn't diminish its enormous value in helping us to arrive at a clearer picture of what actually happened in Britain over a thousand years ago. The entire Chronicle runs to almost 100,000 words. Seven of the nine surviving manuscripts and fragments now reside in the British Library. The remaining two are in the at Oxford and Cambridge universities. http://www.britannia.com/history/docs/asintro2.html Important Results of the Anglo-Saxon and Viking Invasions Politically and Culturally Continued political instability and conflict (i.e., tribal war): there was no central government or church The Anglo-Saxon code (more on this when we read Beowulf) Linguistically The English language is “born” during the first millennium and is known as Old English (OE). Anglo-Saxon is the term for the culture. Old English is mainly Germanic the core of our modern English is vastly influenced by this early linguistic “DNA” MANY dialects of Old-English, as one might imagine. This is because there were five or six different cultures: Angles, Saxons, Frisians, Jutes, Danes, and Swedes *Alfred the Great (ruled from approx. 871-899 A.D.) was one of the first Anglo-Saxon kings to push Vikings back; in fact, he was one of the first kings to begin consolidating power, unifying several of the separate Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. www.classjump.com Huh? (we better boil those important results down!) Lots of ongoing tribal feuds and wars led to . . . Lots of intermingling of similar but different Germanic languages . . . interrupted by . . . MORE Viking invasions, which gave way to . . . Some political unification (Alfred) . . . . . . Which led to . . . OLD ENGLISH, the earliest form of our language!! www.classjump.com The Norman Conquest 1066 In 1042, a descendant of Alfred’s took the throne, the deeply religious Edward the Confessor. Edward, who had no children, had once sworn an oath making his French cousin William, duke of Normandy, his heir—or so William claimed. When Edward died, however, a council of nobles and church officials chose an English earl named Harold to succeed him. Incensed, William led his Norman army in what was to be the last successful invasion of the island of Britain: the Norman Conquest. McDougal Littell, p 20 Harold was killed at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, and on Christmas Day of that year, William the Conqueror was crowned King of England. The Norman Conquest ended Anglo-Saxon dominance in England. Losing their land to the Conquerors, noble Scale model of the Battle of Hastings families sank into the peasantry, and a new class of privileged Normans took their place. McDougal Littell, p 20 A Voice from the Times William returned to Hastings, and waited there to know whether the people would submit Edward the Confessor in his coffin to him. But when he found that Bayeux Tapestry they would not come to him, he went up with all his force that was left and that came since to him from over sea, and ravaged all the country. . . . Harold receives arrow in his eye at —Anglo-Saxon Chronicle the Battle of Hastings and dies. Bayeux Tapestry www.historic-uk.com/.../NormanConquest.htm A Sidebar on the Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry is an embroidery, 1.6 by 230 ft, made in the 11th century. The origin of the tapestry is unknown. The earliest known written reference to it is a 1476 inventory of Bayeaux Cathedral.. It is on display today in Bayeaux, Normandy, France. Celebrating the conquest of England by William, Duke of Normandy, this linen canvas was probably created after the Battle of Hastings on October 14th, 1066 in the south of England by AngloSaxon embroiderers as their work was well-known throughout Europe. Legendary animals, ships, Vikings, Norman and Saxon cavalries illustrate the exploits of William and his opponent Harold, another pretender to the throne of England. http://www.tapestry-bayeux.com/index.php?id=3 The tapestry: 18 inches high and 230 feet long Normans sailing to Hastings Section depicting Halley’s Comet. Death of King Harold Early England Created by Three Invasions 1. Roman Occupation 55 B.C.-410 A.D. 2. Anglo-Saxon and Viking Invasions 410 – 1066 A.D. GERMAN(IC) LATIN (Roman) www.classjump.com 3. The Norman Invasion (The Battle of Hastings) in 1066 A.D. FRENCH Results of the Norman Conquest Two Most Important Effects: French becomes official language of politics and power and exerts enormous influence on Old English England begins unifying under a French political system, much of which is still with us (even in the U.S.) today The Spread of Christianity Like all cultures, that of the Anglo-Saxons changed over time. The early invaders were seafaring wanderers whose lives were bleak, violent, and short. Their pagan religion was marked by a strong belief in wyrd, or fate, and they saved their admiration for heroic warriors whose fate it was to prevail in battle. As the Anglo-Saxons settled into their new land, however, they became an agricultural people— less violent, more secure, more civilized. The bleak fatalism of the Anglo-Saxons’ early beliefs may have reflected the reality of their lives, but it offered little hope. Life was harsh, it taught, and the only certainty was that it would end in death. Christianity opened up a bright new possibility: that the suffering of this world was merely a prelude to the eternal happiness of heaven. Early Anglo-Saxon literature reflected a fatalistic worldview, while later works were influenced by rapidly spreading Christianity. Christianity takes hold No one knows exactly when the first Christian missionaries arrived in Britain, but by a.d. 300 the number of Christians on the island was significant. Over the next two centuries, Christianity spread to Ireland and Scotland, and from Scotland to the Picts and Angles in the north. In 597, a Roman missionary named Augustine arrived in the kingdom of Kent, where he established a monastery at Canterbury. From there, Christianity spread so rapidly that by 690 all of Britain was at least nominally Christian, though many held on to some pagan traditions and beliefs. McDougall Littell p. 21 Monasteries became centers of intellectual, literary, artistic, and social activity. At a time when schools and libraries were completely unknown, monasteries offered the only opportunity for education. Monastic scholars imported books from the Continent, which were then painstakingly copied. In addition, original works were written, mostly in scholarly Latin, but later in Old English. The earliest recorded history of the English people came from the clergy at the monasteries. McDougall Littell p. 21 The greatest of these monks was the Venerable Bede (c. 673–735), author of A History of the English Church and People. When Vikings invaded in the late eighth and ninth centuries, they plundered monasteries and threatened to obliterate all traces of cultural refinement. Yet Christianity continued as a dominant cultural force for more than a thousand years to come. McDougall Littell p. 21 A Sidebar on the Venerable Bede The Venerable Bede (673-735), regarded as the father of English history, lived and worked in a monastery in northern Britain during the late seventh and early eighth centuries. His most famous work, A History of the English Church and People, is a major source of information about life in Britain from the first successful Roman invasion (about a.d. 46) to a.d. 731. The book contains many stories about the spread of Christianity among the English. McDougall Littell, p. 92 http://www.religionfacts.com/ christianity/people/bede.htm First page of Bede’s History, this written in 800 Raised By Monks At the age of seven, Bede was taken by his parents to a monastery at Wearmouth, on the northeast coast of Britain, where he was left in the care of the abbot, Benedict Biscop. It is not known why the boy’s parents left Picture by Ray Pritchard PicturesOfEngland.com him or whether he ever saw them again. When he was nine, Bede moved a short distance to a new monastery at Jarrow, where he McDougall Littell, p. 92 spent the rest of his life. Multitalented Scholar ede was a brilliant scholar and a gifted writer and teacher. He was also a careful and thorough historian. He sought out original documents and reliable eyewitness accounts on which to base his writing. Working in a chilly, damp, poorly lit cell in the monastery, Bede managed to write about 40 books, including works on spelling, grammar, science, history, and religion. McDougall Littell p. 21 A Bookish Boy Bede seems to have been a naturally devout and studious child. He read widely in the monastery libraries and participated fully in the religious life of the monastery. He was exposed to the art and learning of Europe through the paintings, books, and religious objects brought from Rome by Abbot Biscop. Bede became a deacon of the church at the age of 19—six years earlier than was usual—and was ordained to the priesthood when he was 30. McDougall Littell p. 21 Still Venerable Today Bede’s reputation as a scholar and a devout monk spread throughout Europe during his lifetime and in the centuries following. (The honorific title “Venerable” was probably first applied to him during the century after his death, as an acknowledgment of his achievements.) Although Bede was influenced by the outlook of his time—as is evident in the miracle stories he included in his History—his carefulness and integrity are still respected and valued by scholars today, almost 1,300 years later. The tomb of the Venerable Bede McDougall Littell p. 21 Interesting facts: •Bede is the only Englishman that Dante names in the Paradiso. •From Bede’s era came the idea of dating everything from the birth of Christ (AD). Thus, the letters BC (before Christ) may have been started by him. •Bede was the first person to use footnotes---thus they are his invention. •It is believed that the library at his monastery had between 300500 books, making it one of the largest in England and a center for education and culture. •The word Venerable was first attached to his name in the 9th century. It means that his holiness is recognized by the church. The Epic Tradition Anglo-Saxon literature often focused on great Heroes such as Beowulf, though sometimes it addressed everyday concerns. The early literature of the Anglo-Saxon period mostly took the form of lengthy epic poems praising the deeds of heroic warriors. These poems reflected the reality of life at this time, which was often brutal. However, the context in which these poems were delivered was certainly not grim. McDougall Littell p. 21 In poets—bring the epic poems to life. o n s p e c i o a n l s o p c e c c a i s a i l o o n c s c t a o s c i e o l n e s b t r o a c t e e l i heorot.dk McDougall Littell p. 21 In the great mead halls of kings and nobles, Anglo-Saxons would gather on special occasions to celebrate in style. They feasted on pies and roasted meats heaped high on platters, warmed themselves before a roaring fire, and listened to scops— professional poets— bring the epic poems to life. Strumming a harp, the scop would chant in a clear voice that carried over the shouts and laughter of the crowd, captivating them for hours on end with tales of courage, high drama, and tragedy. McDougall Littell p. 21 adventuresindailyliving.blogspot.com matherart.com To the Anglo-Saxons, these epic poems were far more than simple entertainment. The scop’s performance was a history lesson, moral sermon, and pep talk rolled into one, instilling cultural pride and teaching how a true hero should behave. At the same time, in true Anglo-Saxon fashion, the scop reminded his listeners regia.org that they were helpless in the hands of fate and that all human ambition would end in death. With no hope for an afterlife, only an epic poem could provide a measure of immortality. McDougall Littell p. These epic poems were an oral art form: memorized and performed, not written down. Later, as Christianity spread through Britain, literacy spread too, and poems were more likely to be recorded. In this age before printing presses, however, manuscripts had to be written out by hand, copied slowly and laboriously by scribes. McDougall Littell p. illuminatedleaves.com Thus, only a fraction of Anglo-Saxon poetry has survived, in manuscripts produced centuries after the poems were originally composed. The most famous survivor is the epic Beowulf, about a legendary hero of the northern European past. In more than 3,000 lines, Beowulf relates the tale of a heroic warrior who battles monsters and dragons to protect the people. Yet Beowulf, while performing superhuman deeds, is not immortal. His death comes from wounds incurred in his final, great fight. McDougall Littell p. Reflections of Common Life While epics such as Beowulf gave Anglo-Saxons a taste of glory, scops also sang shorter, lyric poems, such as “The Seafarer,” that reflected a more everyday reality: the wretchedness of a cold, wet sailor clinging to his storm-tossed boat; the misery and resentment of his wife, left alone for months or years, not knowing if her husband would ever return. McDougall Littell p. Some of these poems mourn loss and death in the mood of grim fatalism typical of early AngloSaxon times; others, written after the advent of Christianity, express religious faith or offer moral instruction. A manuscript known as the Exeter Book, produced by a single scribe around a.d. 950, contains many of the surviving Anglo-Saxon lyrics, including nearly 100 riddles, religious verse, and a heroic narrative. It is the largest collection of . McDougall Littell p98. Old English poetry in existence. Early Authors Most Old English poems are anonymous. One of the few poets known by name was a monk called Caedmon, described by the Venerable Bede in his famous history of England. Like most scholars of his day, Bede wrote in Latin, the language of the church. It was not until the reign of Alfred the Great that writing in English began to be widespread; in addition to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was written in the language of the people, Alfred encouraged English translations of the Bible and other Latin works. McDougall Littell p98 As England moved into the Middle Ages, its literature continued to capture the rhythms of everyday life. The medieval period was one of social turbulence and unrest, and several works give modern readers a glimpse of the individual hopes and fears of people of the time. Margery Kempe, for example, describes a crisis of faith brought on by childbirth; the letters of Margaret Paston and her family mainly deal with issues of marriage and managing the family estate. McDougall Littell p98 A Short History of Our Language —or— “How English got to be so hard to study, but is still so beautiful to hear and read” www.classjump.com/.../ Quick History of English Language Old English (OE) dates from approximately* 400 A.D. to 1066 Middle English (ME) dates from approximately 1066-1485 They are quite different to the eye and ear. Old English is nearly impossible to read or understand without studying it much like and English speaker today would study French, Latin, or Chinese *The dating of the beginnings of OE is difficult; scholars only have written texts in OE beginning in around 700 A.D., but peoples in England must have been speaking a version of OE prior to works being written in the vernacular (as opposed to Latin) www.classjump.com/.../ Just as Britain’s fifth-century invaders eventually united into a nation called England, their closely related Germanic dialects evolved over time into a distinct language called English— today called Old English to distinguish it from later forms of the language. McDougall Littell p98 A Different Language: Old English was very different from the language we know today. Though about half of our basic vocabulary comes from the Anglo-Saxon language, a modern English speaker would find the harsh sounds impossible to understand. Some words can still be recognized in writing, though the spelling is a little unfamiliar: for instance, sc¯oh (shoe), hunig (honey), milc (milk), and faeder (father). Other words have disappeared entirely, such as hatheart (angry) and gleowian (joke). Another Way of Looking at the History of English Old English 400-1066 Beowulf (from Beowulf!) “Gaæþ a wyrd swa hio scel” (OE) = “Fate goes ever as it must” (MnE) Middle English 1066-1485 Chaucer (from CT) “Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote . . . ” (ME) = “When that April with its sweet showers . . .” (MnE) Early Modern English 1485-1800 Shakespeare “Sir, I loue you more than words can weild ye matter” (EMnE) = (from KL) “Sir, I love you more than word can wield the matter” (MnE) Modern English 1800present Austen (from P&P) It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife. OE=Old English ME=Middle English EMnE=Early Modern English MnE=Modern English A page from the manuscript of Beowulf, reproduced from William J. Long, English Literature: Its History and Its Significance for the Life of the English Speaking World (Boston: Ginn and Co, 1919; repr. as The Project Gutenberg EBook of English Literature, by William J. Long (Project Gutenburg, 2004), http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/0/6/0/10609/10609-h/10609-h.htm#el003) Whan that Apryll with his shoures soote The droghte of March hath perced to the roote, And bathed every veyne in swich licour Of which vertu engendred is the flour; Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth Inspired hath in every holt and heeth The tender croppes, and the yonge sonne Hath in the Ram his half cours yronne, And smale foweles maken melodye, That slepen al the nyght with open ye (So priketh hem Nature in hir corages), Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages, And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes, To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes; its showers sweet drafts vine (root) such liquid West Wind also gover and field young sun (Spring sun) Ram (Aries) his course has run small fowls (little birds) sleep open eye pricks (spurs) spirits Then palmers (pilgrims) strange shores famous halls? foreign shrines? known in (distant) lands And specially from every shires ende shire (country) Of Engeland to Cauterbury they wende, wend (go) The hooly blisful martir for to seke, martir (martyr) seke (seek That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke. Holpen (helped) seeke (sick) Grammatically, the language was more complex than modern English, with words changing form to indicate different functions, so that word order was more flexible than it is now. McDougall Littell p98 The Growth of English The most valuable characteristic of Old English, however, was its ability to change and grow, to adopt new words as the need arose. While Christianity brought Latin words such as cloister, priest, and candle into the Anglo-Saxon vocabulary, encounters with the Vikings brought skull, die, crawl, and rotten. The arrival of the Normans in 1066 would stretch the language even farther, with thousands of words from the French. McDougall Littell p98 English = ? Celtic (from 1700 or 400 B.C. to 55 B.C.) + Latin (from 55 B. C. to 410 A. D.) + German (from 410 A.D. to 1066 A.D.) + French (from 1066 A.D. to 1485 A.D.) = OLD ENGLISH and MIDDLE ENGLISH VERY DIFFICULT LANGUAGE, BUT ONE PERFECT FOR LIMITLESS AND BEAUTIFUL EXPRESSION Transition to Beowulf We study English history to understand the context of the epic, Beowulf; and we study Beowulf to understand the world which was Old England. It is the story of a Scandinavian (Geat) “thane” (warrior or knight) who comes to help a neighboring tribe, the Danes, that is being attacked by a monster. According to Venerable Bede, the Britons called the Romans for help when the Picts and Scots were attacking them (B.C.). Hundreds of years later, the Britons called the Saxons to help them when the Romans couldn’t. The Saxons came “from parts beyond the sea” (qtd. in Pyles and Algeo 96). This journey of Germanic peoples to England “from parts beyond the sea” is the prototypical story for the first millennium of England’s history. It formulates much of their cultural mindset and clearly influences their stories. Be sure to consider how it plays a role in Beowulf. Bibliography Abrams, M. H., and Stephen Greenblatt, Eds. Introduction. The Norton Anthology of English Literature, seventh ed., vol. 1. New York: W.W. Norton, 2000. 1-22, 29-32. Anderson, Robert, et al. Eds. Elements of Literature, Sixth Course, Literature of Britain. Austin: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1993. 2-42. Burrow, J. A. “Old and Middle English Literature, c. 700-1485.” The Oxford Illustrated History of English Literature. Ed. Pat Rogers. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1987. Grant, Neil. Kings and Queens. Glasgow: Harper Collins, 1999. Hollister, C. Warren. The Making of England, 55 B.C. to 1399. 6th ed. Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Heath, 1988 McDougall Littell, Literature. Houghton Miflin. 2009. Pyles, Thomas and John Algeo. The Origins and Development of the English Language. 4th Ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt, 1993.