Beowulf

advertisement

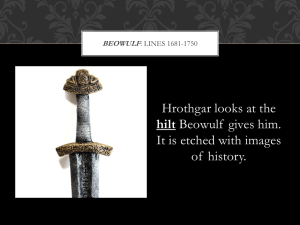

Britain Before the Anglo-Saxons The most important of the early conquerors were the Celts, (with a hard K sound; NOT like Boston Celtics…) who were from southern Europe and migrated /invaded the British Isles between 800 and 600 BCE One group was called Brythons (guess where they landed); the other were known as Gaels who settled in what is now Ireland (Gaelic, get it?) The Celts, briefly Farmers and hunters Tightly-knit clans Druids (a class of priests) settled arguments when clans needed to settle disputes, presided over religious rituals (including sacrifice and prayer) Druids also had the duty of memorizing and reciting long, heroic poems that preserved the people myths about the past (so they are like bards/minstrels/SCOPS Roman Conquest In 55 BC, we have the next set of conquerors, the Romans under Julius Caesar They brought well-paved roads through the woodland wilderness and a highway system, as well as skills in warfare They lasted until around 400 AD, when the Anglo-Saxons showed up Anglo-Saxon Conquest It’s unclear who exactly they were, but historians have some educated guesses. They may have been deep-sea fishermen who were marauding coasts along the Baltic Sea. Or perhaps farmers seeking better soil than the marshy land back home. The Angles and the Saxons were tribes of people who didn’t just perform their piracy to plunder; they sought and won territory, apparently by rowing their shallow boats up the river and then building camps and waging war on the Britons. They gradually gained more and more land and took over what is now England (Angle-land). Anglo-Saxon Conquest: some terms and beliefs The Angles, Saxons, and Jutes transferred to England their highly organized tribal units. Each tribe was ruled by a king who was chosen by a Witan, a council of elders. Four classes: earls – hereditary ruling warlords who owed their position to the king Freeman, who could own land and engage in commerce. This class includes thanes, early barons, who were granted their status as a reward for military service The lowest classes were the serfs (they work the land in return for military protection) and thralls (who are slaves or military prisoners. The Early A/Saxons worshipped ancient Germanic gods (Tiu, god a war and sky; Woden, chief of gods and Fria, Woden’s wife). This is where we get some days of the week. SO…to review: Celts, Roman, AngloSaxons, Scandinavians, Normans Celts invaded in 500 BC Romans invaded in 55 BC, 43 CE and left in 407 CE (Italian) Anglo-Saxons invaded in 449 CE (Germanic) Scandinavians invaded in late 700 CE, 800’s, and end of the 900’s Normans invaded in 1066 CE (France-Normandy) The Coming of Christianity During the 4th century, the Romans had accepted Christianity and introduced it to Britain. A century later, when Celts fled from A/S, they took their Christian faith with them to Wales. From there it spread to Ireland, assisted by St. Patrick It comes back with St. Augustine, who set up a monastery and converted the king and by 650, most of England is Christian in name. It is in this world that Beowulf gets written; the church brings back 2 elements of civilization missing since the time of the Romans: education and written literature Old English (400-1066) Hwæt we Gâr Dena in gear-dagum peod-cyninga prym gefrunon, hu oa æpelingas ellen fremedon Hear me! The Spear Danes in days gone by and the kings who ruled them had courage and greatness. We have heard of those prince’s heroic campaigns. Beowulf Things Which Must Be Known Represents the merging of 2 religions: Pagan and Christianity b/c the missionaries were converting people around the time this story was being passed along through the oral tradition, 500 AD-ish Was written down, probably, by a trained Christian poet b/c it used conventional modes of poetic utterances and traditional poetic forms. Also, the subject matter of poetry was changing from almost all heroic to more religious, as this is a merging of the two The poet himself could’ve been a scop or from a monastery, as most believe, an educated poet who was associated with a monastery It was likely written down around the early 700s to 900s About the Manuscript Some of the Anglo-Saxon poetic devices in it are kennings, alliteration, similes, litotes, antithesis, balance and parallelism, and caesura Some of the characters actually existed The manuscript was saved in the late 1500s. Henry VIII was dissolving the monasteries and so their libraries were in danger. It was saved a # of times from near death (fires have charred away some portion) until in 1753, the British Museum got the original, made two copies (1882 & 1959), and later preserved each page in plastic. An earlier copy of the manuscript was written down sometime around the 11th century CE and is kept in the British Museum Beowulf’s Provenance: So what’s happened to the manuscript since the 11th century? Eventually, it ended up in the library of this guy. Robert Cotton (15711631) Beowulf in the British Museum Setting: Beowulf’s time and place Europe today Insert: Time of Beowulf The Poetry in Beowulf A few things to watch out for 1. Alliterative verse a. Repetition of initial sounds of words (occurs in every line) b. Generally, four feet/beats per line c. A caesura, or pause, between beats two and four, where the scop takes a breath d. No rhyme The Poetry in Beowulf A few things to watch out for Alliterative verse – an example from Beowulf: Oft Scyld Scefing sceapena praetum, Monegum maegpum meodo-setla ofteah; Egsode Eorle, syddan aerest weard. The Poetry in Beowulf A few things to watch out for There was Shield Sheafson, scourge of many tribes, A wrecker of mead-benches, rampaging among foes. The terror of the hall-troops had come far. (Seamus Heaney translation) The Poetry in Beowulf A few things to watch out for 2. Litotes A negative expression; usually an understatement Example: Hildeburh had no cause to praise the Jutes In this example, Hildeburh’s brother has just been killed by the Jutes. This is a poetic way of telling us she hated the Jutes absolutely. Some terms you’ll want to know scop A bard or story-teller. The scop was responsible for praising deeds of past heroes, for recording history, and for providing entertainment Some terms you’ll want to know comitatus Literally, this means “escort” or “comrade” This term identifies the concept of warriors and lords mutually pledging their loyalty to one another Mead Hall The large hall where the lord and his warriors slept, ate, held ceremonies Some terms you’ll want to know wyrd Fate. This idea crops up a lot in the poem, while at the same time there are Christian references to God’s will. But Fate in the Anglo-Saxon world stems from one’s choices. Some terms you’ll want to know elegy An elegy is a poem that is sad or mournful, and it’s usually about death. The adjective is elegaic. werguild Someone’s honor price. The family is compensated for someone’s death. Note that when Hondshew gets eaten by Grendel, this is mentioned Themes and Important Aspects Good vs. Evil Religion: Christian and Pagan influences The importance of wealth and treasure The importance of the sea and sailing The sanctity of the home Fate Loyalty and allegiance Characteristics of a Hero and heroic deeds Epic Poem a LONG narrative poem (it tells a story) on a great and serious subject that - is told in an elevated, formal style (fancy words, very serious, almost ceremonial) - has a heroic or quasi-divine character on whose actions depend the fate of something huge like a nation or the whole human race or the universe. Traditional epics developed from the Oral Tradition, which means historical and legendary tales passed down through generations of story-telling. They are often during a period of expansion and warfare. Classical Epic poems: the Illiad, the Odyssey; AngloSaxon epic: Beowulf Later ones written in deliberate imitation of those above: Virgil’s Aeneid, Milton’s Paradise Lost There are all sorts of rules/conventions these types of tales must follow: hero has to be of great national or cosmic importance. In the Greek ones, he is usually related to the gods somehow (Achilles, Aeneas) the setting must be VAST. So the hero will often go on a long journey that takes years, during which he visits many different lands. There must be superhuman deeds in battle (Achilles, Odysseus, Beowulf) Gods and/or supernatural folks take an active interest or even participate and offer advice All of the previous traits are part of the archetypal hero’s journey, which has several stages. The most important ones for our purpose: the hero has to have a “descent into darkness,” which in the Greek Tales usually means a trip to the Underworld; he also must grow as a character during this journey and return home changed. Odysseus learns from his adventures. He had to experience all these things to become who he is. As Tennyson puts Odysseus’ thoughts, “Much have I seen and known…and drunk delight of battle with my peers, far on the ringing plains of windy Troy. I am a part of all that I have met;” Rules for the Writing Style In the Greek epics, the narrator begins with an invocation to the muse. He’s asking for inspiration so he can tell his tale better. There are 9 muses; one of them (Calliope) is the muse of epic poetry. The Anglo-Saxon scop calls for our attention with “HWAET!” story beings in medias res, in the middle of the action, and then the narrative has flashbacks to catch up to where you began, and then it moves on from there. Notice that in Beowulf, after the prologue, it’s understood that Grendel had been rampaging for 12 winters before Beowulf shows up. Other Elements of Style That You’ll Notice: Epics reflect the important conventions of their time, like the importance of the patriarchal lineage (who’s your daddy?), the role of a good king/warrior, and other patterns you should look for Because these stories were performed, there are lots of repetitive clues and wordplay to keep the characters straight. Homer used epithets (grey-eyed goddess), but the Anglo-Saxons use Kennings (whale-road, sea bench, candle of heaven). The end! What did England Look Like? Petty kingdoms Language – governed by Roman Catholic Church Monastic institutions – cultural identity Danish invasions of the 9th Century – King Alfred’s efforts to institute Latin religious and historical works Secular works like Beowulf were not set in England Sutton Hoo – An AngloSaxon Burial Ground Site was found in 1939 on the property of Mrs. Edith Pretty who died before it was fully excavated Treasures from an Anglo-Saxon Ship burial at Sutton Hoo, Suffolk Treasures collected from Germany, Scandinavia, Alexandria, Byzantium Currently stored at the British Museum The Epic Long narrative poem – story about heroes Epic Conventions – invoke a muse – poet states the subject or purpose of the poem and calls upon a muse In Medias Res – in the middle of things – actions is already underway Elevated style - tone, diction, syntax Supernatural forces Valorous deeds Epic hero – embodies the culture and values and ideals of a nation or culture Major Themes of Beowulf Good versus Evil Christianity’s influence The importance of wealth and treasure Characteristics of a hero Sanctity of home Loyalty and Allegiance Bravery Fate Beowulf’s Provenance It is set in Scandinavia (what is now Sweden) Tribe known as the Geats Set around 400-500 CE There are Vikings Christian references…pagan ideals long since past Oral Tradition Monsters, Dragons, Kings, Princes, Magic, and more…. It all starts with a monster…and a scop Literary Elements of Beowulf Kennings – two-word poetic renamings like “Whales’ home” for the sea, compound nouns Assonance – repeated vowele sounds in unrhymed stressed syllables Alliteration – repeated initial consonant sounds in stressed syllables Parallelism – parataxis series of parallel constructions strung toether one after another using coordinating conjunctions such as and.. Metonymy – object linked to another object where an object stands for another – suits for businessmen, shield for the people, etc. Litotes – understatement, generally ironic and sometimes even humorous using negatives and double negatives Elegy – a poem mourning the loss of someone or something