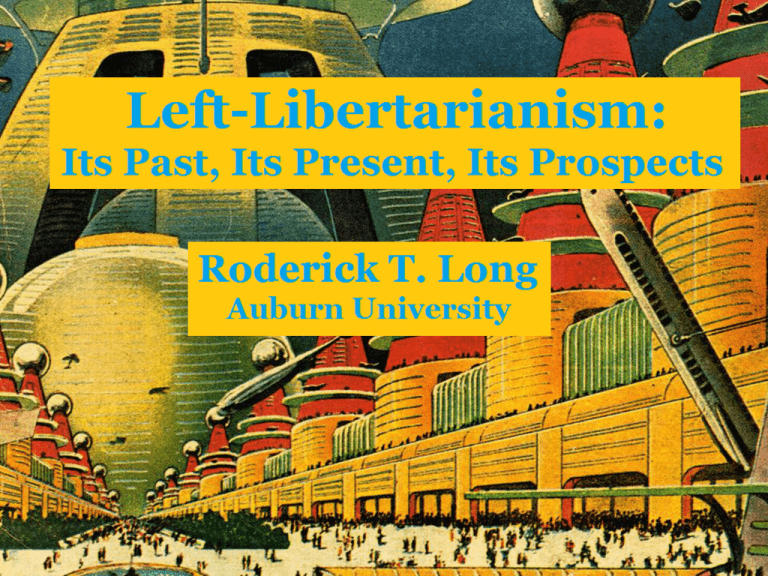

left-libertarians

advertisement

What I do NOT mean by “left-libertarianism” • The Vallentyne-Otsuka-Steiner (VOS) position that combines self-ownership with common resource ownership (dubbed “left-libertarianism” in the 1990s) • The communist anarchist position (occasionally dubbed “left-libertarianism” in the early 1900s, but more frequently in the 1970s What I DO mean by “left-libertarianism” A movement • growing out of the rapprochement of market libertarianism and the New Left in the 1960s and 70s, but • having roots in the individualist anarchism of the 19th century, and • emerging in its current form over the past decade. Terminological Prolegomena • The term “libertarian” (as “libertaire”), designating a specific political position, originates in 1857 with Joseph Déjacque as term for his own communist anarchism • By the 1880s it is also being used by marketoriented anarchists, e.g. in Benjamin Tucker’s journal Liberty • Nowadays French has two words for “libertarian”: “libertaire” (Déjacquean) and “libertarien” (market) Terminological Prolegomena • The term “left-libertarian” appears to emerge as a way of differentiating anarchist communism from market libertarianism • Hence “left-libertarian” becomes more common as “libertarian” becomes more common • Attested as early as 1917, it’s still uncommon before the mid-1970s Terminological Prolegomena • A new sense of “left-libertarian” (but still two decades older than the VOS sense) emerges in the 1970s • This is the most common sense within the libertarian movement itself • Unlike the Déjacquean and VOS senses, this sense refers to a form of, not an alternative to, market libertarianism: the “left wing” of the market libertarian movement Terminological Prolegomena • One early use of “leftlibertarian” in this sense: Roy A. Childs Jr., “How Bad is the U.S. Government?,” The Abolitionist, May 1971 • Samuel E. Konkin III’s “Movement of the Libertarian Left” dates from 1978 Usual Features of Left-Libertarianism • radical (usually anarchistic) commitment to freed markets, private property, and laissez-faire • opposition to hierarchical workplaces, corporate dominance, and gross economic inequality as evils both akin to and largely enabled by statism • opposition to forms of social privilege such as racism, sexism, homophobia, and cissexism, as evils both akin to statism and standing in relationships of mutual support with it Usual Features of Left-Libertarianism • orientation toward class analysis • opposition to militarism, nationalism, and intellectual property • support for environmentalism and open borders • preference for restitution over punishment • strategic emphasis on education, direct action, and building alternative institutions, rather than electoral politics Distinct From Bleeding-Heart Libertarianism • BHL combines free markets with social justice concerns, as do left-libertarians • But BHL is broader; includes not only left-libertarians (whose leftism and libertarianism reinforce each other: fusing Rothbard with Graeber) but also liberaltarians (whose leftism and libertarianism moderate each other: fusing Hayek with Rawls) Origins of Left-Libertarianism • In one sense, left-libertarianism can be traced back to the English Levellers of the 1640s • But if we’re looking for a movement that is seen, and sees itself, as a) marketlibertarian, but b) significantly to the “left” of other market libertarians, the early 19th century seems to be our starting point Origins of Left-Libertarianism • First Wave: 19th-century individualist anarchists • Second Wave: the libertarian / New Left rapprochement of the 1960s-70s • Third Wave: the past decade Before the First Wave: The Industrialist Theory of Class Crucial prehistory of left-libertarianism: the “Industrialist”: movement • leaders of authoritarian wing: Auguste Comte, Henri de Saint-Simon • leaders of libertarian wing: Charles Comte, Charles Dunoyer, Augustin Thierry • journal of libertarian wing: Le Censeur (18141815) and its successor, Le Censeur Européen (1817-1820) Before the First Wave: The Industrialist Theory of Class “Industrialists” anticipate Marx: • in seeing society as the scene of a struggle between an exploiting and an exploited (“industrious”) class • in looking forward to a social transformation that will end this class division forever Before the First Wave: The Industrialist Theory of Class “Industrialists” differ from Marx: • in seeing differential access to political power rather than differential access to the means of production as the crucial enabler of exploitation • this class division cuts across that between capitalists and workers Before the First Wave: The Industrialist Theory of Class “Industrialists” differ from one another: • authoritarian wing’s solution: replace aristocrats in the top political slots with representatives of the industrious class (anticipates Marx’s dictatorship of the proletariat) • libertarian wing’s solution: dismantle the political hierarchy itself rather than merely changing the personnel (anticipates Marx’s withering of the state) Before the First Wave: The Industrialist Theory of Class • States are “monstrous aggregations ... formed and made necessary by the spirit of domination .... [The] spirit of industry will dissolve them [and] municipalise the world [as] centers of actions ... multiply.” – Charles Dunoyer • “Federations will replace states; the chains of interest ... will succeed the despotism of men and of laws; the tendency toward government ... will cede to the free community .... The era of empire is finished; the era of association begins.” – Augustin Thierry Before the First Wave: The Industrialist Theory of Class Liberals influenced by the Censeur group and their theory of class: • Adolphe-Jérôme Blanqui • Frédéric Bastiat • Gustave de Molinari • probably James Mill: “We must call to mind the division which philosophers have made of men placed in society. ... The first class, Ceux qui pillent, are the small number. They are the ruling Few. The second class, Ceux qui sont pillés, are the great number. They are the subject Many.” Marx vs. the Industrialist Theory of Class “No credit is due to me for discovering the existence of classes in modern society or the struggle between them. Long before me bourgeois historians had described the historical development of this class struggle and bourgeois economists, the economic economy of the classes. ... Marx vs. the Industrialist Theory of Class ... What I did that was new was to prove: (1) that the existence of classes is only bound up with particular historical phases in the development of production ... (2) that the class struggle necessarily leads to the dictatorship of the proletariat, (3) that this dictatorship itself only constitutes the transition to the abolition of all classes and to a classless society.” Marx vs. the Industrialist Theory of Class Marx’s claim that the “bourgeois economists/historians” did not anticipate an end to class conflict is: • incorrect if “class” is understood as they understood it (in terms of access to political power) • correct if “class” is understood as Marx understands it (in terms of monopolisation of the means of production) The Censeur group did not challenge the separation of labour from ownership Marx vs. the Industrialist Theory of Class “When one casts a superficial glance at even the best organised societies, and sees, beside a large number of men who live off the products of their lands, a still larger number who have nothing to live on but the products of their daily labour, one is tempted to consider the former as clever usurpers and the latter as dupes or victims; one would readily demand that the division be done anew so that each might have his share. ... Marx vs. the Industrialist Theory of Class ... This apparent injustice disappears, at least in great part, when one admits in principle that every man is the proprietor of the values that he has created; when one observes the way in which property is formed and the way in which the various classes increase their numbers. Fortunes made by fraud or violence are the only ones that morality and justice may condemn.” – Charles Comte Marx vs. the Industrialist Theory of Class Here Comte • acknowledges the attractiveness of a Marxianstyle means-of-production version of class analysis • nonetheless rejects it in favour of a Censeur-style force-and-fraud version • assumes that the division between propertied employers and propertyless workers is “at least in great part” legitimate, because NOT the product of force or fraud Left-Libertarianism’s First Wave • For the Censeur group, political violence explains pre-capitalist economic divisions but not capitalist ones • For Marx, by contrast, the “historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production” is “written in the annals of mankind in letters of blood and fire” • The left-libertarian agrees with the Censeur group on property rights but with Marx on history Left-Libertarianism’s First Wave For individualist anarchist Thomas Hodgskin, “the share claimed by the capitalist for the use of fixed capital” is “derived from the whole surface of the country, having been at one period monopolised by a few persons,” since the landlord is “the descendant of those who forcibly appropriated,” while the capitalist, by “obtaining from the landlord interest or profit on his property, shared his power.” Left-Libertarianism’s First Wave • Proper basis of property rights for Hodgskin: Lockean homesteading via labour-mixing, “ordained by nature” • Basis of capitalist property rights: violent usurpation “created and protected by the law” • Hodgskin grounds a means-ofproduction class theory in a political-power class theory Left-Libertarianism’s First Wave • Hodgskin both criticises and is criticised by other radical market liberals more favourable to capitalism • Hodgskin’s Labour Defended (a reference to James Mill’s Commerce Defended) includes Mill among those whose “notions of the nature and utility of capital” he aims to “refute” • Mill for his part says that Hodgskin’s “mad nonsense ... would be the subversion of civilised society; worse than the overwhelming deluge of Huns and Tartars” • Charles Knight adds that Hodgskin would give us “skins instead of cloth, hollow trees instead of houses” Left-Libertarianism’s First Wave • With Hodgskin a position emerges that is clearly identifiable as a) a radical form of market libertarianism, but b) to the left of mainstream market libertarianism • Similar ideas emerge slightly later, apparently independently, in France (P.-J. Proudhon) and the United States (anarchist-feminist-abolitionists Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews) • Their views are inherited by the American individualist anarchists, including Ezra and Angela Heywood, Lysander Spooner, William B. Greene, Benjamin Tucker, and Voltairine de Cleyre (many called themselves socialists and were members of the First International) Tucker’s Four Monopolies • land monopoly (use-andoccupancy as criterion for continued ownership) • money monopoly (mutual banking will free credit) • tariff monopoly • patent monopoly And underlying all four, the state monopoly Tucker’s Four Monopolies Spooner disagrees with Tucker on need for ongoing land use to retain property titles, but agrees that • much landed property has been established by legal privilege rather than homesteading • freer markets would undermine the wage system by increasing opportunities for self-employment (whether individual or collective); working for an employer would become an option, not a necessity Left-Libertarianism’s First Wave • Tucker condemns anti-market socialists like Marx, who thinks that the “only way to abolish the class monopolies” is to “centralize and consolidate all industrial and commercial interests, all productive and distributive agencies, in one vast monopoly in the hands of the State.” • Tucker also condemns right-wing libertarians like Herbert Spencer and the Manchester liberals for “believ[ing] in liberty to compete with the laborer in order to reduce his wages, but not in liberty to compete with the capitalist in order to reduce his usury.” Left-Libertarianism’s First Wave • “Liberty’s aim – universal happiness – is that of all Socialists, in contrast with that of the Manchester men – luxury fed by misery. But its principle – individual sovereignty – is that of the Manchester men, in contrast with that of the Socialists – individual subordination. But individual sovereignty, when logically carried out, leads, not to luxury fed by misery, but to comfort for all industrious persons ....” – Benjamin R. Tucker Left-Libertarianism’s Second Wave • During the early 20th century, libertarians drift into an alliance with conservatives against state socialism • Left-libertarianism becomes less prominent • In the 1960s, partly in response to the rise of the New Left (including historians like Gabriel Kolko’s), it is revived by Murray Rothbard, Karl Hess, Robert Anton Wilson, and others • Rothbardian Carl Oglesby becomes president of the Students for a Democratic Society Left-Libertarianism’s Second Wave • Hess defines the “left wing” as “the side of politics and economics that opposes the concentration of power and wealth and, instead, advocates and works toward the distribution of power into the maximum number of hands.” • The abolition of slavery is a “great unfinished business,” since merely “setting slaves free, in a world still owned by their masters,” is unjust. • Libertarianism seeks to “advance principles of property,” but not to “defend ... all property which now is called private.” Left-Libertarianism’s Second Wave Rothbard likewise places libertarianism on the left and conservatism (the “polar opposite of liberty”) on the right, seeing state-socialism as a “confused, middle-ofthe road movement” that accepts “the liberal goals of freedom, reason, mobility, progress, higher living standards the masses, and an end to theocracy and war; but [tries] to achieve these ends by the use of incompatible, Conservative means: statism, central planning, communitarianism.” Left-Libertarianism’s Second Wave • “Regulations that present-day Rightists think of as ‘socialistic’ were not only uniformly hailed, but conceived and brought about by big businessmen. This was a conscious effort to fasten upon the economy a cement of subsidy, stabilization, and monopoly privilege.” • Rothbard even calls for worker takeover of government-funded corporations (e.g. military-industrial complex) • Does not challenge the wage system, but some Rothbardians (e.g. Konkin) do Left-Libertarianism’s Third Wave • With collapse of the New Left, Rothbard begins a retreat toward a more right-wing form of libertarianism • Konkin continues to develop an “agorist” libertarian left, focusing on counter-economic action to undermine the state • In the 1990s, Chris M. Sciabarra develops a left-friendly dialectical libertarian theory drawing on Marx, F. A. Hayek, and Ayn Rand Left-Libertarianism’s Third Wave • In the 21st century’s first decade, a new left-libertarianism emerges, drawing on Hodgskin, Tucker, Rothbard, Hess, Wilson, Konkin, and Sciabarra, as well as on antimarket anarchists like Kropotkin • Leading figures include Kevin Carson, Charles W. Johnson, and Gary Chartier • Competition is seen as a levelling force; vast inequalities are hard to sustain if imitation is permitted Kevin Carson Carson follows Tucker in defending • a subjectivised version of the labour theory of value (disutility of providing good sets lower price limit; competition sets upper price limit) • a use-and-occupancy theory of property rights (natural rights specify some form of private property but not what kind; pragmatic considerations specify more) But Carson stresses that his conclusions do not depend, for the most part, on these premises Kevin Carson Carson combines, updates, and extends: • Hodgskin’s and Marx’s accounts of the historical origin of the capitalist monopoly of the means of production in government intervention • Tucker’s, Kolko’s, and Rothbard’s accounts of the ways in which state privilege continues to benefit capital at the expense of labour • Rothbard’s and Hess’s calls for redistribution of property arising from state privilege Kevin Carson Carson’s terminology: • Vulgar libertarianism: treating the virtues of a free market as though they legitimised existing corporate capitalism (example: Ayn Rand) • Vulgar liberalism: treating the evils of existing corporate capitalism as though they constituted an objection to free markets (example: Noam Chomsky) These enable conservatives to pose as foes of big government and liberals to pose as foes of big business, when both in practice support business-government partnership Kevin Carson • As firms grow larger and more hierarchical, diseconomies of scale overtake economies of scale – unless state privilege insulates them from competition • It is labour legislation, not the nature of unions, that diverts unions from being agents of worker empowerment to being labour cartels • What is called deregulation leaves “primary” pro-business regulations in place and removes only “secondary” alleviatory regulations, thus increasing state intervention Gary Chartier on “Capitalism” • “capitalism1: an economic system that features personal property rights and voluntary exchanges of goods and services • capitalism2: an economic system that features a symbiotic relationship between big business and government • capitalism3: rule – of workplaces, society, and ... the state – by capitalists” Gary Chartier on “Capitalism” • Three senses are frequently conflated but are actually incompatible: support for capitalism1 negates capitalism2 and thereby undermines capitalism3 • The word “capitalism” suggests a system favouring capital owners over labourers and so should be abandoned by free-market advocates, since genuinely freed markets empower workers • Equation of markets with the cash nexus should also be resisted Left-Libertarianism’s Third Wave • Left-libertarians also revive and extend the 19thcentury individualist anarchists’ commitments to feminism, antiracism, antimilitarism, environmentalism, etc. • Like their 19th-century forebears, leftlibertarians see statism, patriarchy, white supremacy, homophobia etc. as mutually reinforcing forms of oppression, and thus as demanding a unified, activist, but nongovernmental response Charles Johnson on Hayek and Feminism “‘Spontaneous order’ can be used to mean a macroscale pattern of social coordination which is: • Consensual rather than coercive (when ‘spontaneous’ means ‘uncoerced’); • Polycentric or participatory rather than directive (when ‘spontaneous’ means ‘unprompted’); or • Emergent rather than a consciously designed pattern (when ‘spontaneous’ means ‘not planned in advance’)” Charles Johnson on Hayek and Feminism Disentangling these usually conflated senses allows for the possibility of • polycentric and undesigned but nonconsensual orders (rape culture) • consensual and participatory but designed orders (Wikipedia, grassroots activism) The first shows why libertarians are wrong to think only state action is oppressive The second shows why feminists are wrong to think only state action can combat oppression Charles Johnson on Thick vs. Thin Libertarianism Libertarians as libertarians must embrace certain values causally or conceptually connected with, even though not entailed by, the nonaggression principle (NAP) • grounds thickness: values entailed by the best reasons for NAP (anti-authoritarianism) • application thickness: values needed in order to apply NAP correctly (animal rights) • strategic thickness: causal preconditions for implementing NAP (gross economic inequality) • consequence thickness: opposing independently bad things caused by NAP violations (sweatshops) Advantage of Left-Libertarianism • Should the baseline for mutual advantage be equality (Rawls) or natural entitlement (Nozick)? • Nozickian “historical” justice lays bare the causes of inequality in class domination and so does better, not worse, job than Rawls of condemning existing inequalities (despite Nozick’s intentions) • Rawlsian and Nozickian standards usually thought to conflict: means-of-production class theory à la Marx favours egalitarian baseline while Censeur-style force-and-fraud class theory favours natural-entitlement baseline • But if means-of-production class theory can be grounded in forceand-fraud class theory à la Hodgskin, Tucker, and Carson, we don’t have to choose but can accommodate the intuitions supporting both baselines Advantage of Left-Libertarianism What of counterfactual conflicts between the baselines? Options: • choose property rights over economic equality • choose economic equality over property rights • forge a compromise through mutual adjustment • deny the possibility of systematic conflicts for beings like us These are the same options raised by conflict between consequentialism and deontology and so are no special problem for left-libertarianism

![Kaikoura Human Modification[1]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005232493_1-613091dcc30a5e58ce2aac6bd3fb75dd-300x300.png)