Background

Black and marginalised individuals may be suspicious of

social service interventions influenced by discourses of

family dysfunction (Agozino, 1997; Barn, 2001; Bernard and

Gupta, 2008; Lees, 2002), further explored in first person

narratives of Black British women abused as children (Briscoe,

2009; Mason-John, 2005; Riley, 1985; Williams, 2011).

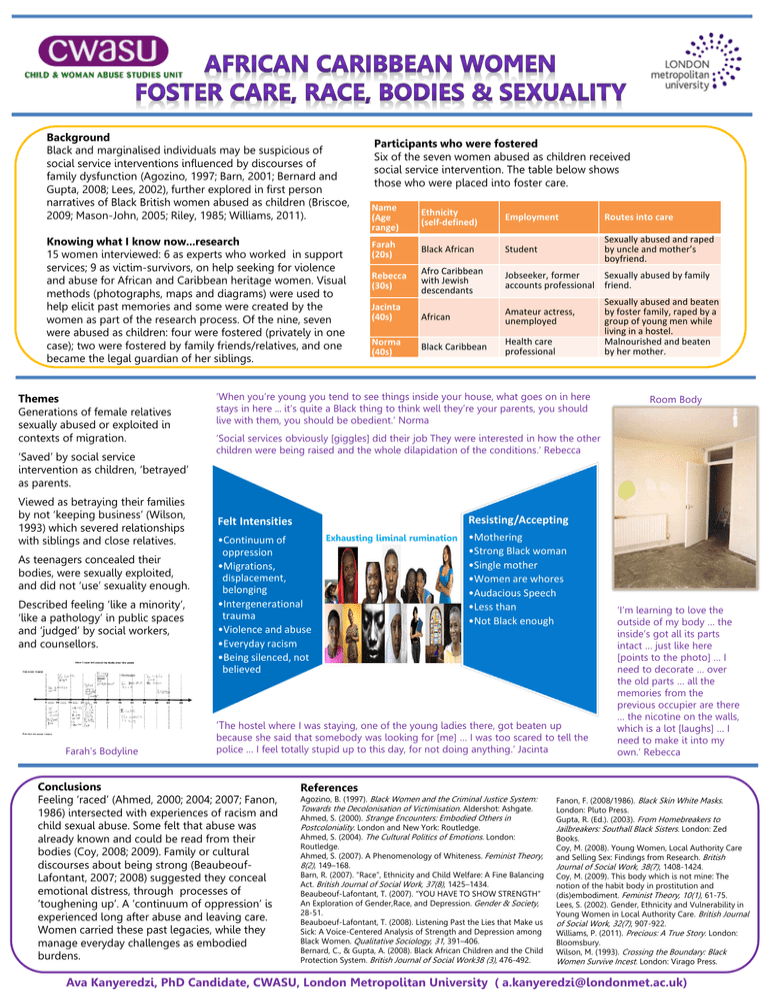

Knowing what I know now...research

15 women interviewed: 6 as experts who worked in support

services; 9 as victim-survivors, on help seeking for violence

and abuse for African and Caribbean heritage women. Visual

methods (photographs, maps and diagrams) were used to

help elicit past memories and some were created by the

women as part of the research process. Of the nine, seven

were abused as children: four were fostered (privately in one

case); two were fostered by family friends/relatives, and one

became the legal guardian of her siblings.

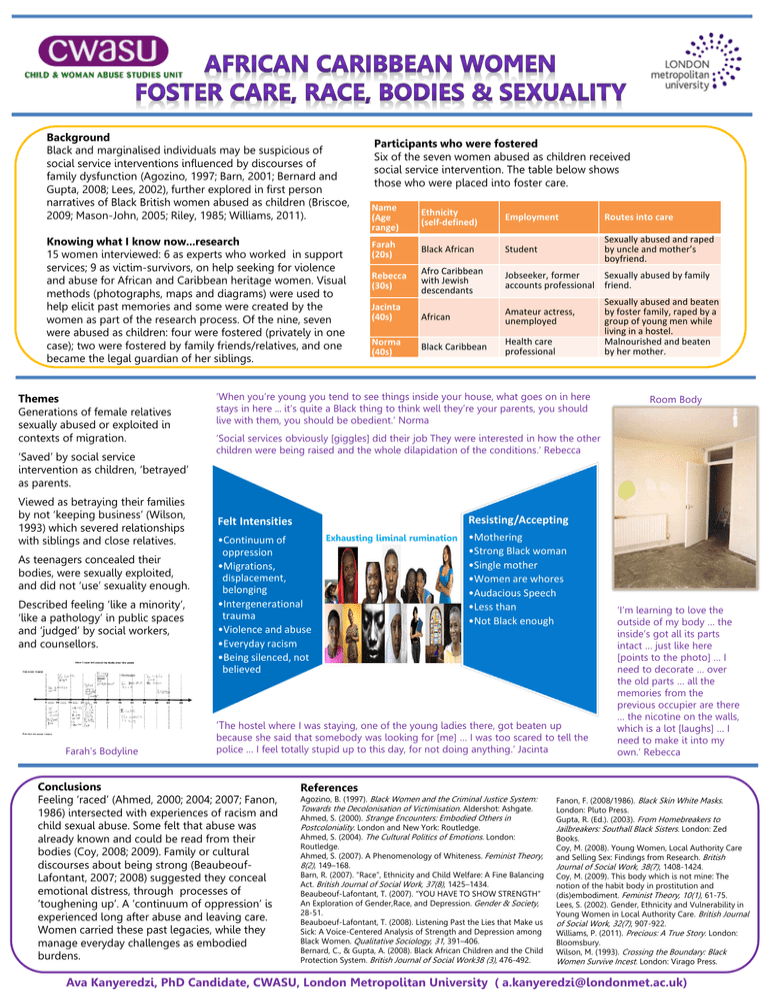

Participants who were fostered

Six of the seven women abused as children received

social service intervention. The table below shows

those who were placed into foster care.

Name

(Age

range)

Ethnicity

(self-defined)

Employment

Routes into care

Farah

(20s)

Black African

Student

Sexually abused and raped

by uncle and mother’s

boyfriend.

Rebecca

(30s)

Afro Caribbean

with Jewish

descendants

Jobseeker, former

Sexually abused by family

accounts professional friend.

Jacinta

(40s)

African

Amateur actress,

unemployed

Norma

(40s)

Black Caribbean

Health care

professional

Sexually abused and beaten

by foster family, raped by a

group of young men while

living in a hostel.

Malnourished and beaten

by her mother.

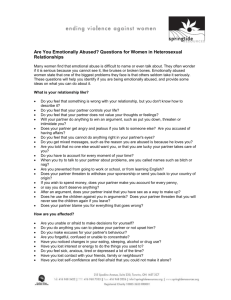

Room body

Themes

Generations of female relatives

sexually abused or exploited in

contexts of migration.

‘Saved’ by social service

intervention as children, ‘betrayed’

as parents.

Viewed as betraying their families

by not ‘keeping business’ (Wilson,

1993) which severed relationships

with siblings and close relatives.

As teenagers concealed their

bodies, were sexually exploited,

and did not ‘use’ sexuality enough.

Described feeling ‘like a minority’,

‘like a pathology’ in public spaces

and ‘judged’ by social workers,

and counsellors.

‘When you’re young you tend to see things inside your house, what goes on in here

stays in here ... it’s quite a Black thing to think well they’re your parents, you should

live with them, you should be obedient.’ Norma

‘Social services obviously [giggles] did their job They were interested in how the other

children were being raised and the whole dilapidation of the conditions.’ Rebecca

Resisting/Accepting

Felt Intensities

•Continuum of

oppression

•Migrations,

displacement,

belonging

•Intergenerational

trauma

•Violence and abuse

•Everyday racism

•Being silenced, not

believed

Exhausting liminal rumination

•Mothering

•Strong Black woman

•Single mother

•Women are whores

•Audacious Speech

•Less than

•Not Black enough

‘The hostel where I was staying, one of the young ladies there, got beaten up

Farah’s Bodyline

Room Body

because she said that somebody was looking for [me] … I was too scared to tell the

police … I feel totally stupid up to this day, for not doing anything.’ Jacinta

Conclusions

Feeling ‘raced’ (Ahmed, 2000; 2004; 2007; Fanon,

1986) intersected with experiences of racism and

child sexual abuse. Some felt that abuse was

already known and could be read from their

bodies (Coy, 2008; 2009). Family or cultural

discourses about being strong (BeaubeoufLafontant, 2007; 2008) suggested they conceal

emotional distress, through processes of

‘toughening up’. A ‘continuum of oppression’ is

experienced long after abuse and leaving care.

Women carried these past legacies, while they

manage everyday challenges as embodied

burdens.

‘I’m learning to love the

outside of my body … the

inside’s got all its parts

intact … just like here

[points to the photo] … I

need to decorate … over

the old parts … all the

memories from the

previous occupier are there

… the nicotine on the walls,

which is a lot [laughs] … I

need to make it into my

own.’ Rebecca

References

Agozino, B. (1997). Black Women and the Criminal Justice System:

Towards the Decolonisation of Victimisation. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Ahmed, S. (2000). Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in

Postcoloniality. London and New York: Routledge.

Ahmed, S. (2004). The Cultural Politics of Emotions. London:

Routledge.

Ahmed, S. (2007). A Phenomenology of Whiteness. Feminist Theory,

8(2), 149–168.

Barn, R. (2007). “Race”, Ethnicity and Child Welfare: A Fine Balancing

Act. British Journal of Social Work, 37(8), 1425–1434.

Beaubeouf-Lafontant, T. (2007). “YOU HAVE TO SHOW STRENGTH”

An Exploration of Gender,Race, and Depression. Gender & Society,

28-51.

Beauboeuf-Lafontant, T. (2008). Listening Past the Lies that Make us

Sick: A Voice-Centered Analysis of Strength and Depression among

Black Women. Qualitative Sociology, 31, 391–406.

Bernard, C., & Gupta, A. (2008). Black African Children and the Child

Protection System. British Journal of Social Work38 (3), 476-492.

Fanon, F. (2008/1986). Black Skin White Masks.

London: Pluto Press.

Gupta, R. (Ed.). (2003). From Homebreakers to

Jailbreakers: Southall Black Sisters. London: Zed

Books.

Coy, M. (2008). Young Women, Local Authority Care

and Selling Sex: Findings from Research. British

Journal of Social Work, 38(7), 1408-1424.

Coy, M. (2009). This body which is not mine: The

notion of the habit body in prostitution and

(dis)embodiment. Feminist Theory, 10(1), 61-75.

Lees, S. (2002). Gender, Ethnicity and Vulnerability in

Young Women in Local Authority Care. British Journal

of Social Work, 32(7), 907-922.

Williams, P. (2011). Precious: A True Story. London:

Bloomsbury.

Wilson, M. (1993). Crossing the Boundary: Black

Women Survive Incest. London: Virago Press.

Ava Kanyeredzi, PhD Candidate, CWASU, London Metropolitan University ( a.kanyeredzi@londonmet.ac.uk)