Pearson_Basketball

advertisement

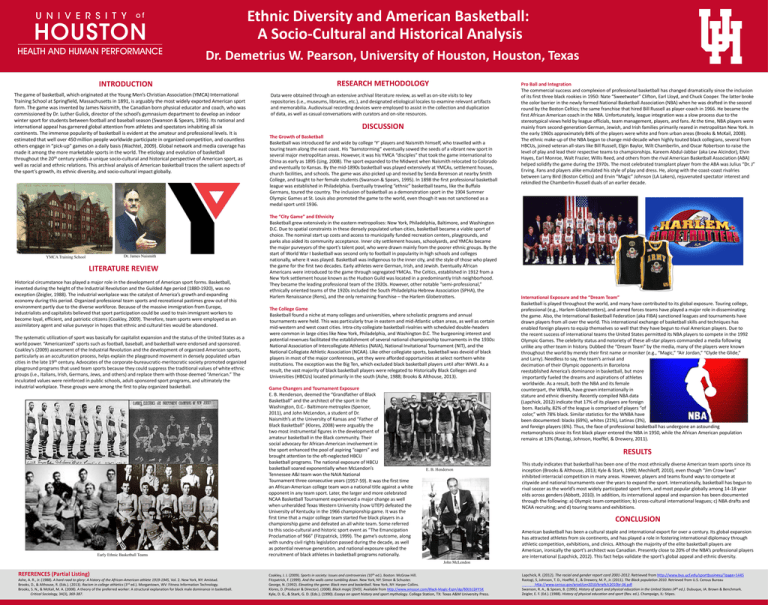

Ethnic Diversity and American Basketball: A Socio-Cultural and Historical Analysis Dr. Demetrius W. Pearson, University of Houston, Houston, Texas INTRODUCTION The game of basketball, which originated at the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) International Training School at Springfield, Massachusetts in 1891, is arguably the most widely exported American sport form. The game was invented by James Naismith, the Canadian born physical educator and coach, who was commissioned by Dr. Luther Gulick, director of the school’s gymnasium department to develop an indoor winter sport for students between football and baseball season (Swanson & Spears, 1995). Its national and international appeal has garnered global attention from athletes and spectators inhabiting all six continents. The immense popularity of basketball is evident at the amateur and professional levels. It is estimated that well over 450 million people worldwide participate in organized competition, and countless others engage in “pick-up” games on a daily basis (Wachtel, 2009). Global network and media coverage has made it among the more marketable sports in the world. The etiology and evolution of basketball throughout the 20th century yields a unique socio-cultural and historical perspective of American sport, as well as racial and ethnic relations. This archival analysis of American basketball traces the salient aspects of the sport’s growth, its ethnic diversity, and socio-cultural impact globally. Dr. James Naismith YMCA Training School LITERATURE REVIEW Historical circumstance has played a major role in the development of American sport forms. Basketball, invented during the height of the Industrial Revolution and the Guilded Age period (1880-1920), was no exception (Zeigler, 1988). The industrial workplace was the catalyst of America’s growth and expanding economy during this period. Organized professional team sports and recreational pastimes grew out of this environment partly due to the diverse workforce. Because of the massive immigration from Europe, industrialists and capitalists believed that sport participation could be used to train immigrant workers to become loyal, efficient, and patriotic citizens (Coakley, 2009). Therefore, team sports were employed as an assimilatory agent and value purveyor in hopes that ethnic and cultural ties would be abandoned. The systematic utilization of sport was basically for capitalist expansion and the status of the United States as a world power. “Americanized” sports such as football, baseball, and basketball were endorsed and sponsored. Coakley’s (2009) assessment of the Industrial Revolution and the development of organized American sports, particularly as an acculturation process, helps explain the playground movement in densely populated urban cities in the late 19th century. Advocates of the corporate-bureaucratic-meritocratic society promoted organized playground programs that used team sports because they could suppress the traditional values of white ethnic groups (i.e., Italians, Irish, Germans, Jews, and others) and replace them with those deemed “American.” The inculcated values were reinforced in public schools, adult-sponsored sport programs, and ultimately the industrial workplace. These groups were among the first to play organized basketball. Early Ethnic Basketball Teams RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Data were obtained through an extensive archival literature review, as well as on-site visits to key repositories (i.e., museums, libraries, etc.), and designated etiological locales to examine relevant artifacts and memorabilia. Audiovisual recording devices were employed to assist in the collection and duplication of data, as well as casual conversations with curators and on-site resources. DISCUSSION The Growth of Basketball Basketball was introduced far and wide by college ‘Y’ players and Naismith himself, who travelled with a touring team along the east coast. His “barnstorming” eventually sowed the seeds of a vibrant new sport in several major metropolitan areas. However, it was his YMCA “disciples” that took the game international to China as early as 1895 (Ling, 2008). The sport expanded to the Midwest when Naismith relocated to Colorado and eventually to Kansas. By the mid-1890s basketball was played extensively at YMCAs, settlement houses, church facilities, and schools. The game was also picked up and revised by Senda Berenson at nearby Smith College, and taught to her female students (Swanson & Spears, 1995). In 1898 the first professional basketball league was established in Philadelphia. Eventually traveling “ethnic” basketball teams, like the Buffalo Germans, toured the country. The inclusion of basketball as a demonstration sport in the 1904 Summer Olympic Games at St. Louis also promoted the game to the world, even though it was not sanctioned as a medal sport until 1936. The “City Game” and Ethnicity Basketball grew extensively in the eastern metropolises: New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington D.C. Due to spatial constraints in these densely populated urban cities, basketball became a viable sport of choice. The nominal start up costs and access to municipally funded recreation centers, playgrounds, and parks also aided its community acceptance. Inner city settlement houses, schoolyards, and YMCAs became the major purveyors of the sport’s talent pool, who were drawn mainly from the poorer ethnic groups. By the start of World War I basketball was second only to football in popularity in high schools and colleges nationally, where it was played. Basketball was indigenous to the inner city, and the style of those who played the game for the first two decades. Early athletes were German, Irish, and Jewish. Eventually African Americans were introduced to the game through segregated YMCAs. The Celtics, established in 1912 from a New York settlement house known as the Hudson Guild was located in a predominantly Irish neighborhood. They became the leading professional team of the 1920s. However, other notable “semi-professional,” ethnically oriented teams of the 1920s included the South Philadelphia Hebrew Association (SPHA), the Harlem Renaissance (Rens), and the only remaining franchise – the Harlem Globetrotters. The College Game Basketball found a niche at many colleges and universities, where scholastic programs and annual tournaments were held. This was particularly true in eastern and mid-Atlantic urban areas, as well as certain mid-western and west coast cities. Intra-city collegiate basketball rivalries with scheduled double-headers were common in large cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. The burgeoning interest and potential revenues facilitated the establishment of several national championship tournaments in the 1930s: National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA), National Invitational Tournament (NIT), and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). Like other collegiate sports, basketball was devoid of black players in most of the major conferences, yet they were afforded opportunities at select northern white institutions. The exception was the Big Ten, which excluded black basketball players until after WWII. As a result, the vast majority of black basketball players were relegated to Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) located primarily in the south (Ashe, 1988; Brooks & Althouse, 2013). Game Changers and Tournament Exposure E. B. Henderson, deemed the “Grandfather of Black Basketball” and the architect of the sport in the Washington, D.C.- Baltimore metroplex (Spencer, 2011), and John McLendon, a student of Dr. Naismith’s at the University of Kansas and “Father of Black Basketball” (Klores, 2008) were arguably the two most instrumental figures in the development of amateur basketball in the Black community. Their social advocacy for African-American involvement in the sport enhanced the pool of aspiring “cagers” and brought attention to the oft-neglected HBCU basketball programs. The national exposure of HBCU basketball soared exponentially when McLendon’s Tennessee A&I team won the NAIA National Tournament three consecutive years (1957-59). It was the first time an African-American college team won a national title against a white opponent in any team sport. Later, the larger and more celebrated NCAA Basketball Tournament experienced a major change as well when unheralded Texas Western University (now UTEP) defeated the University of Kentucky in the 1966 championship game. It was the first time that a major college team started five black players in a championship game and defeated an all white team. Some referred to this socio-cultural and historic sport event as “The Emancipation Proclamation of 966” (Fitzpatrick, 1999). The game’s outcome, along with sundry civil rights legislation passed during the decade, as well as potential revenue generation, and national exposure spiked the recruitment of black athletes in basketball programs nationally. Pro Ball and Integration The commercial success and complexion of professional basketball has changed dramatically since the inclusion of its first three black rookies in 1950: Nate “Sweetwater” Clifton, Earl Lloyd, and Chuck Cooper. The latter broke the color barrier in the newly formed National Basketball Association (NBA) when he was drafted in the second round by the Boston Celtics; the same franchise that hired Bill Russell as player-coach in 1966. He became the first African American coach in the NBA. Unfortunately, league integration was a slow process due to the stereotypical views held by league officials, team management, players, and fans. At the time, NBA players were mainly from second-generation German, Jewish, and Irish families primarily reared in metropolitan New York. In the early 1960s approximately 84% of the players were white and from urban areas (Brooks & McKail, 2008). The ethnic make-up of the NBA began to change mid-decade when highly touted black collegians, several from HBCUs, joined veteran all-stars like Bill Russell, Elgin Baylor, Wilt Chamberlin, and Oscar Robertson to raise the level of play and lead their respective teams to championships. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (aka Lew Alcindor), Elvin Hayes, Earl Monroe, Walt Frazier, Willis Reed, and others from the rival American Basketball Association (ABA) helped solidify the game during the 1970s. The most celebrated transplant player from the ABA was Julius “Dr. J” Erving. Fans and players alike emulated his style of play and dress. He, along with the coast-coast rivalries between Larry Bird (Boston Celtics) and Ervin “Magic” Johnson (LA Lakers), rejuvenated spectator interest and rekindled the Chamberlin-Russell duals of an earlier decade. International Exposure and the “Dream Team” Basketball is played throughout the world, and many have contributed to its global exposure. Touring college, professional (e.g., Harlem Globetrotters), and armed forces teams have played a major role in disseminating the game. Also, the International Basketball Federation (aka FIBA) sanctioned leagues and tournaments have drawn players from all over the world. This international exchange of basketball skills and techniques has enabled foreign players to equip themselves so well that they have begun to rival American players. Due to the recent success of international teams the United States permitted its NBA players to compete in the 1992 Olympic Games. The celebrity status and notoriety of these all-star players commanded a media following unlike any other team in history. Dubbed the “Dream Team” by the media, many of the players were known throughout the world by merely their first name or moniker (e.g., “Magic,” “Air Jordan,” “Clyde the Glide,” and Larry). Needless to say, the team’s arrival and decimation of their Olympic opponents in Barcelona reestablished America’s dominance in basketball, but more importantly fueled the dreams and aspirations of athletes worldwide. As a result, both the NBA and its female counterpart, the WNBA, have grown internationally in stature and ethnic diversity. Recently compiled NBA data (Lapchick, 2012) indicate that 17% of its players are foreign born. Racially, 82% of the league is comprised of players “of color,” with 78% black. Similar statistics for the WNBA have been documented: blacks (69%), whites (21%), Latinas (3%), and foreign players (6%). Thus, the face of professional basketball has undergone an astounding metamorphosis since its first black player entered the NBA in 1950, while the African American population remains at 13% (Rastogi, Johnson, Hoeffel, & Drewery, 2011). RESULTS E. B. Henderson This study indicates that basketball has been one of the most ethnically diverse American team sports since its inception (Brooks & Althouse, 2013; Kyle & Stark, 1990; Mechikoff, 2010), even though “Jim Crow laws” inhibited interracial competition in many areas. However, players and teams found ways to compete at citywide and national tournaments over the years to expand the sport. Internationally, basketball has begun to rival soccer as the world’s most widely participated sport form, and most popular globally among 14-18 year olds across genders (Abbott, 2010). In addition, its international appeal and expansion has been documented through the following: a) Olympic team competition; b) cross-cultural international leagues; c) NBA drafts and NCAA recruiting; and d) touring teams and exhibitions. CONCLUSION American basketball has been a cultural staple and international export for over a century. Its global expansion has attracted athletes from six continents, and has played a role in fostering international diplomacy through athletic competition, exhibitions, and clinics. Although the majority of the elite basketball players are American, ironically the sport’s architect was Canadian. Presently close to 20% of the NBA’s professional players are international (Lapchick, 2012). This fact helps validate the sport’s global appeal and ethnic diversity. John McLendon REFERENCES (Partial Listing) Ashe, A. R., Jr. (1988). A hard road to glory: A history of the African-American athlete 1919-1945, Vol. 2. New York, NY: Amistad. Brooks, D., & Althouse, R. (Eds.). (2013). Racism in college athletics (3rd ed.). Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology. Brooks, S. N., & McKail, M. A. (2008). A theory of the preferred worker: A structural explanation for black male dominance in basketball. Critical Sociology, 34(3), 369-387. Coakley, J. J. (2009). Sports in society: Issues and controversies (10th ed.). Boston: McGraw Hill. Fitzpatrick, F. (1999). And the walls came tumbling down. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. George, N. (1992). Elevating the game: Black men and basketball. New York, NY: Harper Collins. Klores, D. (Producer & Director). (2008). Black magic [DVD]. Available from http://www.amazon.com/Black-Magic-Espn/dp/B001CDFY5K Kyle, D. G., & Stark, G. D. (Eds.). (1990). Essays on sport history and sport mythology. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. Lapchick, R. (2012). The racial and gender report card 2001-2012. Retrieved from http://www.bus.ucf.edu/sportbusiness/?page=1445 Rastogi, S, Johnson, T. D., Hoeffel, E., & Drewery, M. P., Jr. (2011). The Black population 2010. Retrieved from U.S. Census Bureau http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-06.pdf Swanson, R. A., & Spears, B. (1995). History of sport and physical education in the United States (4th ed.). Dubuque, IA: Brown & Benchmark. Zeigler, E. F. (Ed.). (1988). History of physical education and sport (Rev. ed.). Champaign, IL: Stipes.