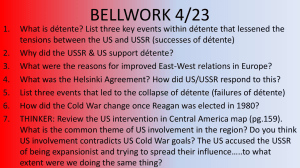

Challenges to Detente

advertisement

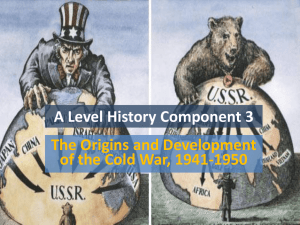

Limitations to Success The achievements of détente, although significant, were limited. Even at its height, in the early 1970s, there were still confrontations between the superpowers and by the later 1970s many US politicians were deeply hostile to the policy. Within President Carter’s administration (19771981), there were deep divisions over détente; Cyrus Vance, the Security of State, generally supported its continuation whilst Zbigniew Brzezinski, Carter’s National Security Adviser, was very aggressive towards the USSR and very skeptical about détente. President Carter himself was very keen to link détente to human rights concessions by the USSR and this attempt at “linkage” angered the Soviet leadership. Ironically what was probably Carter’s greatest diplomatic achievement, his part in the Camp David Agreement of 1978 and the subsequent Egyptian-Israeli Peace treaty of 1979, undermined détente because in brokering the settlement carter had gone back on an earlier promise that the USSR would be involved in any Middle Eastern peace negotiations. By the late 1970s there were growing challenges to the continuation of détente and it is clear that it had totally collapsed by 1980 when a “Second Cold War” was begun. Included is a list of the most important challenges to détente which contributed to its eventual collapse. The Yom Kippur War, 1973 This Arab-Israeli conflict showed up the limitations of Détente as during it the USA and the USSR were drawn into a major confrontation. Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack on Israel in October 1973 and made big advances into Israel. The USA airlifted military equipment to Israel and the Israeli armed forces counterattacked successfully, crossing the Suez Canal and surrounding an entire Egyptian army. At this point Brezhnev proposed that a joint USSoviet military force be sent to Egypt to impose a ceasefire on the Arab and Israeli forces and threatened to send Soviet troops alone if the USA failed to agree. President Nixon responded very strongly, rejecting this proposal and putting US forces on world-wide alert. The USSR backed down and accepted the US suggestion of a UN peacekeeping force. In late October the UN imposed a ceasefire on the Arabs and Israelis which the Israelis reluctantly accepted. The Yom Kippur War showed that détente was only partly successful in improving EastWest relations; there remained the possibility of renewed conflict. Détente survived the Yom Kippur War but from 1976 onwards the process was increasingly under pressure. Soviet Intervention in Africa Of particular importance in the collapse of détente was Soviet intervention in the developing world. Whist the USSR saw in détente a means of securing stable and peaceful relations in Europe, the Soviet leadership did not accept that détente should restrain the USSR from seeking to extend its influence in the developing world. Soviet influence in the developing world was much more limited than that of the USA and the USSR refused to accept that inferior position. In particular the USSR was eager to establish close relations with countries which might provide the Soviet navy with bases. At the start of the 1970s the Soviet navy lacked naval bases outside of the USSR itself which meant that although its Navy was bigger than that of the USA, the USSR could not keep its fleet and submarines at sea as long as the Americans and their NATO allies could. Between 1967 and 1972 the USSR was granted naval facilities in Egypt following Soviet military aid to Egypt in the Six Day War (1967) but in 1972 Soviet-Egyptian relations broke down. President Sadat expelled thousands of Soviet advisers and refused to allow the Soviet navy to continue to use Egyptian ports. The mid to late 1970s saw the USSR exploit a number of opportunities for intervention in Africa which alarmed the USA and contributed to a souring of US-Soviet relations. Until 1974, Angola was a Portuguese colony. In 1974 a military coup overthrew the right-wing Portuguese dictator, Marcelle Caetano. There had been resistance to Portuguese rule in Angola since the 1950s; The MPLA (the Moviment Popular de Liberatacao de Angola) was established in 1956, the FNLA (Frente Nacional de Liberatacao de Angola) in 1962 and UNITA (the Uniao Nacional para a Independencia Total de Angola) in 1966. The Portuguese granted Angola independence in 1975 which led to civil war between a coalition of FNLA-UNITA forces and the MPLA. The FNLA-UNITA forces received help from South Africa, including South African ground troops, and some limited military supplies from the USA. However, the US Congress, after discovering that President Ford, had already provided unauthorized aid to the FNLA-UNITA, refused to vote money for further aid. By contrast, the USSR provided substantial military supplies to the MPLA as well as Russian military advisers. More importantly Cuba sent 17,000 troops to fight alongside the MPLA. Soviet and Cuban aid helped tip the balance in the MPLA’s favour and by early 1976 the MPLA controlled most of Angola. The US administration was very concerned at this successful Soviet intervention in Southern Africa. In spite of the MPLA’a success, UNITA’s guerrilla war against the MPLA regime continued into the 1980s. The USSR had close linked in the 1970s with both Ethiopia and Somalia but in 1977-1978 the USSR intervened on the side of the Ethiopia when it went to war with Somalia over the disputed Ogaden region. The USSR provided Ethiopia with military supplies but again Cuba went further sending 17,000 troops to fight on Ethiopia’s side. Ethiopia won the war and the USSR benefited by being granted the use of Ethiopian ports. Once more the USA saw this as Soviet aggression and the Right in the US politics criticized détente for failing to curb Soviet expansionism. However, the USSR was reacting to events in the Horn of Africa, it did not provoke the crisis and would have preferred to remain on good terms with both Ethiopia and Somalia. The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan, 1979 This was arguably the event that finally killed off the process of détente and did most to provoke the “Second Cold War” Soviet intervention in Afghanistan was very different from the USSR’s involvement in Angola and Ethiopia. This time, although the Soviet leadership had anticipated a brief military operation, the USSR found itself bogged sown in a full scale war lasting nine years and costing over 15,000 Soviet soldiers lives. The origins of the USSR’s intervention lay in a successful coup by a left-wing Afghan group, the PDPA (the People’[s Democratic Party of Afghanistan), in April 1978, which overthrew the regime headed by General Mubammed Daoud. The PDPA aligned themselves with the USSR, signing a Friendship Treaty in December 1978. The PDPA, led by Muhamed Tarakki, introduced a range of radical reforms, including measures to emancipate women, which offended Islamic fundamentalists. This resulted in the outbreak of civil war, which intensified in 1979. The Afghan rebel groups received support from Pakistan and Iran, and, the USSR suspected CIA involvement too. Also causing concerns to the USSR was the internal feuding within the PDPA between the Khalq and Parcham factions. Also causing concern to the USSR was internal feuding within the PDPA between the Khalq and Parcham factions. In October 1979 Hafizullah Amin had Tarakki arrested and executed and became the new president. However, the Amin regime failed to prevent the civil war from escalating and did not end the PDPA’s factionfailed. In December 1979 the USSR sent 85,000 troops into Afghanistan and installed a new president, Babrak Karmal, leader of the Parcham faction (Amin, leader of the Khalqs, was executed). The Soviet leadership invaded Afghanistan with intention of preserving a left-wing, pro-Soviet government on its border. The USSR was anxious to prevent the collapse of the PDPA regime because it feared that a successful Islamic fundamentalist revolution in Afghanistan would incite unrest among the millions of Muslims who were Soviet citizens. The concern was understandable given the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979 which brought the Ayatollah Khomeni to power. The Republicans launched scathing attacks on Carter for failing to prevent yet more Soviet “expansionism”. Consequently, President Carter reacted very strongly to the Soviet invasion, declaring that it was the most serious threat to world peace since the end of World War Two. In January 1980, Carter end his attempts to get SALT II Treaty ratified by the Senate (where it would not have passed in any case), It placed an embargo on certain US exports to the USSR, including grain, banned American involvement in the Moscow Olympics. Promised to increase defence spending by 5% each year in real terms over the next five years. Détente was now finally killed off. The Deployment of SS-20s & Cruise Missiles The late 1970s saw an intensification of the nuclear arms race, with both superpowers developing and deploying more technologically advanced intermediate ranged nuclear missiles. This development increased international tensions. In 1977 the USSR began to deploy the SS-20, a new type of intermediate range nuclear missile, based in the USSR itself and targeted on Western Europe and China. The SS-20 was moveable from one launch site to another, had a longer range than the SS-4 and SS-5 which it replaced, and was a MIRV. The USA decided, in response, to deploy their own new intermediate missiles, the Cruise and Pershing II. Cruise missiles flew at low levels to avoid detection by radar and so were seen as a weapon that could be used for a surprise attack. The USA’s Western European alli4es had asked the USA to deploy the new missiles to counter the Soviet SS-20s. In December 1979, NATO announced that, from 1983, 108 Pershing II missiles would be sited in West Germany and 464 Tomahawk cruise missiles in five Western European countries. This decision alarmed the USSR which saw them as evidence that the USA might consider a successful first strike against the USSR as possible option. It also caused a storm of protest from antinuclear groups in Western Europe e.g. from CND (the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament) in the UK. The Rise of the “New Right” in US Politics Within US politics, the “New Right” emerged: an alliance of Republicans and conservative Democrats who favoured substantial increases in defence spending as both a way of deterring Soviet expansionism and of pulling the US economy out of the severe recession that it had suffered since 1973-1974. The New Right saw détente as fundamentally flawed, describing it as a “one-way street”; they argued that the USA had entered into the spirit of détente but the USSR had not. They (the New Right) believed that the Soviet leadership had cynically exploited détente, refusing to improve their record on human rights in the Eastern bloc and increasingly seeking to intervene in the developing world.