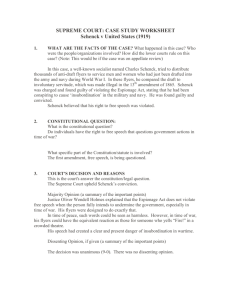

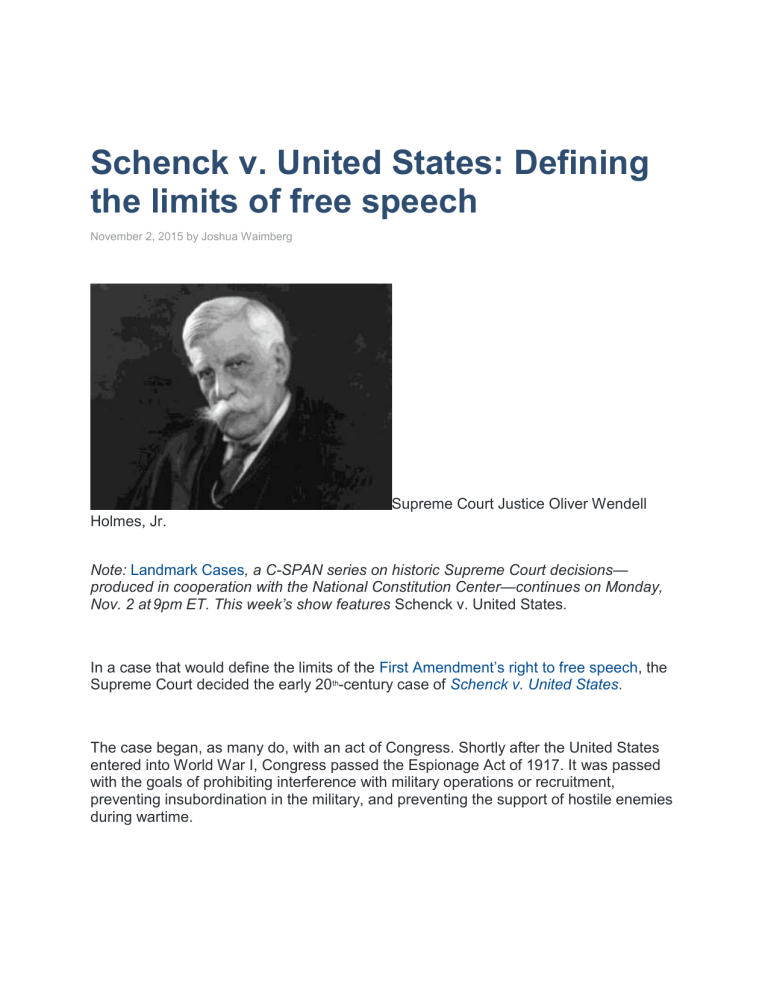

Schenck v. United States: Defining the limits of free speech November 2, 2015 by Joshua Waimberg Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Note: Landmark Cases, a C-SPAN series on historic Supreme Court decisions— produced in cooperation with the National Constitution Center—continues on Monday, Nov. 2 at 9pm ET. This week’s show features Schenck v. United States. In a case that would define the limits of the First Amendment’s right to free speech, the Supreme Court decided the early 20th-century case of Schenck v. United States. The case began, as many do, with an act of Congress. Shortly after the United States entered into World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act of 1917. It was passed with the goals of prohibiting interference with military operations or recruitment, preventing insubordination in the military, and preventing the support of hostile enemies during wartime. At the time, Charles Schenck was an important Philadelphia socialist. He was the general secretary of the Socialist Party of America, and was opposed to the United States’ entry into the war. As part of his efforts to counter the war effort, Schenck organized the distribution of 15,000 leaflets to prospective military draftees encouraging them to resist the draft. The leaflet began with the heading, “Long Live The Constitution Of The United States; Wake Up America! Your Liberties Are in Danger!” It went on to quote Section One of the 13th Amendment, which outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude. Schenck’s leaflet asserted that the draft amounted to involuntary servitude because “a conscripted citizen is forced to surrender his right as a citizen and become a subject.” The leaflet’s other side, titled “Assert Your Rights,” told conscripts that, “[i]f you do not support you rights, you are helping to ‘deny or disparage rights’ which it is the solemn duty of all citizens and residents of the United States to retain.” Schenck was arrested, and, among other charges, was indicted for “conspir[ing] to violate the Espionage Act … by causing and attempting to cause insubordination … and to obstruct the recruiting and enlistment service of the United States.” Schenck and Elizabeth Baer, another member of the Socialist Party who was also charged, were both convicted following a jury trial and sentenced to six months in prison. Schenck and Baer appealed their convictions to the Supreme Court. They argued that their convictions—and Section Three of the Espionage Act of 1917, under which they were convicted—violated the First Amendment. They claimed that the Act had the effect of dissuading and outlawing protected speech about the war effort, thereby abridging the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech. In a unanimous decision written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Supreme Court upheld Schenck’s conviction and found that the Espionage Act did not violate Schenck’s First Amendment right to free speech. The Court determined that Schenck had, in fact, intended to undermine the draft, as the leaflets instructed recruits to resist the draft. Additionally, even though the Act only applied to successful efforts to obstruct the draft, the Court found that attempts made by speech or writing could be punished just like other attempted crimes. When it came to the Act’s alleged violation of the First Amendment, the Court found that context was the most important factor. The Court said that, while “in many places and in ordinary times” the leaflet would have been protected, the circumstances of a nation at war allowed for greater restrictions on free speech. Justice Holmes wrote, “When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in a time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.” Holmes famously analogized the United States’ position in wartime to that of a crowded theater: The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic … The question in every case is whether the words are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. This quote, while famous for its analogy, also gave the Court a pragmatic standard to use when faced with free speech challenges. The “clear and present danger” standard encouraged the use of a balancing test to question the state’s limitations on free speech on a case-by-case basis. If the Court found that there was a “clear and present danger” that the speech would produce a harm that Congress had forbidden, then the state would be justified in limiting that speech. It was only a year later that Holmes attempted to redefine the standard. In the 1919 case of Abrams v. United States, the Justice reversed his position and dissented, questioning the government’s ability to limit free speech. Holmes did not believe that the Court was applying the “clear and present danger” standard appropriately in the case, and changed its phrasing. He wrote that a stricter standard should apply, saying that the state could restrict and punish “speech that produces or is intended to produce clear and imminent danger that it will bring about forthwith certain substantive evils that the United States constitutionally may seek to prevent.” But the “clear and present danger” standard would last for another 50 years. In Brandenburg v. Ohio, a 1969 case dealing with free speech, the Court finally replaced it with the “imminent lawless action” test. This new test stated that the state could only limit speech that incites imminent unlawful action. This standard is still applied by the Court today to free speech cases involving the advocacy of violence. The Espionage Act of 1917 lives on as well. Since the decision in Schenck v. United States, those who have been charged under the act include Socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs, executed communists Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, and Pentagon Papers whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg. Most recently, both Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden have also been charged under the Act. Joshua Waimberg is a legal fellow at the National Constitution Center. Filed Under: First Amendment, Freedom of Speech, Supreme Court, Speech and Press Clause OPO.COM UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT AND POLITICS Daily Briefing, Supreme Court Cases A cropped image of the pamphlet at issue. Clear and Present Danger. The first time the Supreme Court examined a federal conviction on a free speech claim was in Schenck v. United States (1919). As the United States entered World War I, the 1917 Sedition and Espionage Acts prevented publications that criticized the government, that advocated treason, insurrection, or that brought disloyal behavior in the military. A U.S. district court tried and convicted Charles Schenck, the secretary of the Socialist party, when he printed 15,000 anti-draft leaflets intended for Philadelphia-area draftees. His pamphlet cited the Thirteenth Amendment and claimed that a mandatory military U.S. draft (a procedure also known as conscription) amounted to involuntary servitude denied by that amendment. Schenck appealed his guilty verdict. The Court drew a distinction between speech that communicated honest opinion and speech that incited unlawful action. In a unanimous opinion written by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes and delivered after the war’s end, the Court upheld the government’s right to define and convict citizens for certain speech. Schenk went to prison as did defendants in five similar cases. The clear and present danger test became the balancing act between competing demands of free expression and a government needing to protect a free society. . . . In impassioned language, [the pamphlet] intimated that conscription was despotism in its worst form, and a monstrous wrong against humanity in the interest of Wall Street’s chosen few . . . It described the arguments on the other side as coming from cunning politicians and a mercenary capitalist press, and even silent consent to the conscription law as helping to support an infamous conspiracy . . . Of course, the document would not have been sent unless it had been intended to have some effect, and we do not see what effect it could be expected to have upon persons subject to the draft except to influence them to obstruct the carrying of it out . . . We admit that, in many places and in ordinary times, the defendants, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force. The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.Oliver Wendell Holmes Analyze and Interpret: 1. What was unique about Schenck’s case and the time of this controversy? 2. How did the Supreme Court decide his appeal? 3. What standard did the Court develop to determine if the speech might go too far?