Uploaded by

hamza hamdan

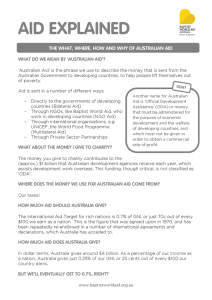

Progressive Realism: Australian Foreign Policy in the 21st Century

advertisement