U N I V E R S I T Y OF C A L G A R Y

Reinforced Concrete Beam Design for Shear

by

Hongge (Gordon) Wang

A THESIS

S U B M I T T E D TO T H E F A C U L T Y OF G R A D U A T E STUDIES

IN P A R T I A L F U L F I L L M E N T OF T H E R E Q U I R E M E N T S F O R T H E

D E G R E E OF M A S T E R OF E N G I N E E R I N G

D E P A R T M E N T OF CIVIL E N G I N E E R I N G

CALGARY, ALBERTA

N O V E M B E R , 2002

© Hongge (Gordon) Wang 2002

The author of this thesis has granted the University of Calgary a non-exclusive

license to reproduce and distribute copies of this thesis to users of the University

of Calgary Archives.

Copyright remains with the author.

Theses and dissertations available in the University of Calgary Institutional

Repository are solely for the purpose of private study and research. They may

not be copied or reproduced, except as permitted by copyright laws, without

written authority of the copyright owner. Any commercial use or re-publication is

strictly prohibited.

The original Partial Copyright License attesting to these terms and signed by the

author of this thesis may be found in the original print version of the thesis, held

by the University of Calgary Archives.

Please contact the University of Calgary Archives for further information:

E-mail: uarc@ucalgary.ca

Telephone: (403) 220-7271

Website: http://archives.ucalgary.ca

ABSTRACT

The two methods for design of shear adopted by the present C S A Standard A23.3

are either too simple or too complicated. That presents the need for ongoing research to

establish a new design guideline for shear design.

Recent studies by Dr. Loov and others have shown that shear design can be based

on the shear resistance along potential inclined crack and slip planes. Because the basic

equations for this shear design method are derived from "shear friction" theories, we call

it "the shear friction method".

In this thesis an entire review of shear design methods has been given and a

method of shear design based on shear friction theories has been introduced. From

comparison calculations with present code methods it is proved that "the shear friction

method" provides a simpler and more accurate approach for shear design.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am extremely grateful to my supervisor, Dr. Robert E. Loov for his endless

patience and guidance throughout the course of this program.

I would also like to thank my current employer Kassian Dyck & Associates for

giving me the chance to finish this thesis.

Finally I wish to thank my wife Candy for her support and encouragement.

iv

T A B L E OF C O N T E N T S

Cover Page

i

Approval page

ii

Abstract

iii

Acknowledgements

iv

Table of Contents

v

List of Tables

viii

List of Figures

ix

Notation

xiii

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1

1.1 General

1

1.2 Code Review

2

1.3 Scope of Study

3

1.4 Thesis Organization

3

C H A P T E R T W O : B A S I C S H E A R THEORIES

5

2.1 Homogeneous Beam

5

2.2 Beam Cracking Modes

9

2.3 Shear Transfer Mechanisms

10

2.4 Shear Failure Modes

12

2.4.1 Beams without Shear Reinforcement

12

2.4.2 Beams with Shear Reinforcement

16

2.5 Factors Affecting the Shear Strength

16

2.5.1 Tensile Strength of Concrete

16

2.5.2 Longitudinal Reinforcement

17

2.5.3 Shear Span-to-depth Ratio, a/d

17

2.5.4 Size of Beams

19

v

2.5.5 Axial Forces

20

2.5.6 Web Reinforcement

20

C H A P T E R T H R E E : S H E A R DESIGN - C S A S T A N D A R D A23.3-94

22

3.1 General

22

3.2 Simplified Method

22

3.2.1 Shear Supported by Concrete, V

3.2.2 Shear Supported by Stirrups, V

23

c

25

s

3.3 General Method

25

3.3.1 Shear Supported by Concrete, V

3.3.2 Shear Supported by Stirrups, V

26

c g

26

s g

C H A P T E R F O U R : S H E A R DESIGN - S H E A R FRICTION M E T H O D

27

4.1 General

27

4.2 General Equations for Beams Based on Shear Friction

27

4.2.1 Shear Friction Strength

28

4.2.2 Basic Shear Design Equations Based on Work by Loov

31

4.2.3 Approximate Shear Capacity of Concrete

36

4.2.4 Approximate Shear Capacity of Stirrups

40

4.2.5 Approximate Shear Design Equations for Beams with

T>T

40

opl

4.2.6 Critical Shear Failure Angle

41

4.2.7 Beams with Longitudinal Reinforcement T<T ,

op

C H A P T E R F I V E : E X P E R I M E N T A L STUDIES A N D C O M P A R I S O N

44

45

5.1 Application of Shear Friction Method

45

5.2 Test Results in Literature

47

5.2.1 Yoon, Cook and Mitchell's Tests, 1996

48

5.2.2 Saram and Al-Musawi's Tests, 1992

58

vi

5.2.3 Summary of Tests from Literature

71

5.2.3.1 Beams with Shear Reinforcement

79

5.2.3.2 Beams without Shear Reinforcement

93

C H A P T E R SIX: P R O P O S E D C O D E C L A U S E S F O R S H E A R D E S I G N

106

6.1 Proposed Code Clauses for Shear Design

106

6.1.1 Required Shear Resistance

106

6.1.2 Factored Shear Resistance

106

6.1.3 Determination of V

c s f

106

6.1.4 Determination of V

s s f

107

6.1.5 Determination of 0

107

6.1.6 Determination of \|/

108

6.1.7 Limiting Shear Failure Angle

108

6.2 Design Examples

108

C H A P T E R S E V E N : DISCUSSION A N D C O N C L U S I O N

7.1 Conclusions and Recommendations

7.2 Future Research

BIBLIOGRAPHY

111

Ill

112

113

vii

LIST OF T A B L E S

TABLE

5.1 Details of Beam Specimens (Yoon)

5.2 Test Results and Comparison of Predictions (Yoon)

5.3 Details of Beam Specimens (Sarsam)

5.4 Details of Materials (Sarsam)

5.5 Test Results and Comparison of Predictions (Sarsam)

5.6 Details of Specimens with Stirrups

5.7 Details of Specimens without Stirrups

5.8 Comparison of Predictions for Beams with Stirrups

5.9 Comparison of Predictions for Beams without Stirrups

viii

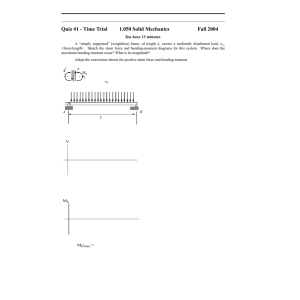

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE

2.1

Internal Forces in Beam

5

2.2 Distribution of Flexural Shear Stresses

6

2.3 Principal Stresses

7

2.4a Stress Trajectories

8

2.4b Potential Crack Pattern

8

2.5 A Cracked Beam without Shear Reinforcement (MacGregor, 2000)

9

2.6 A Cracked Beam with Shear Reinforcement (Peng, 1999)

10

2.7 Internal Forces in a Cracked Beam

11

2.8 Effect of a/d on Shear for Beams Without Shear Reinforcement (MacGregor,

2000)

14

2.9 Shear Failure Modes (Pillai, 1983)

15

2.10 Shear Strength vs. Longitudinal Reinforcement (MacGregor, 2000)

17

2.11 Shear Strength vs. a/d (Kani, 1979)

18

2.12 Influence of Member Size on Shear Strength (CSA A23.3-94)

19

2.13 Effect of Axial Loads in Inclined Cracking Shear (MacGregor, 2000)

20

2.14 Distribution of Internal Shears of Beam with Shear

Reinforcement

(MacGregor, 2000)

21

3.1

Comparison of Shear Design Methods and Test Results ( C S A A23.3-94)

24

4.1

Shear Friction Concept (CSA A23.3-94)

28

4.2 Reinforcement Inclined to Potential Failure Cracks ( C S A A23.3-94)

29

4.3

Push-off Test Results (Loov, 1998)

30

4.4 Free Body Diagram of Beam (Loov, 1998)

31

4.5

34

Shear Strength vs. Crack Angle (Loov, 1998)

ix

4.6 Three-dimensional surface of shear strength along all possible failure planes

for beam 544 (Loov, 1998)

34

4.7 Possible Critical Shear Failure Planes (Loov, 1999)

35

4.8 A Tested Beam with Critical Shear Cracks (Peng, 1999)

35

4.9

37

Shear Strength vs. cotO

4.10 Shear Strength vs. cot9 by Eq. 4-15 and Eq. 4-19

38

4.11 Shear Strength vs. Longitudinal Reinforcement of Beam

39

4.12 The Shear Contributions of Concrete and Discrete Stirrups (Loov, 1998)

42

5.1

Details of Beam Specimens and instrumentation (Yoon, 1996)

48

5.2

Effect of Concrete Strength on the Shear Friction Method (Yoon)

51

5.3

Effect of Concrete Strength on the Simplified Method (Yoon)

52

5.4 Effect of Concrete Strength on the General Method (Yoon)

52

5.5

Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the Shear Friction Method (Yoon)

53

5.6 Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the Shear Friction Method (Yoon)

54

5.7 Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the Simplified Method (Yoon)

54

5.8

55

Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the Simplified Method (Yoon)

5.9 Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the General Method (Yoon)

55

5.10 Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the General Method (Yoon)

56

5.11 Effect of Concrete Strength on the Shear Friction Method (Yoon)

57

5.12 Effect of Concrete Strength on the Simplified Method (Yoon)

57

5.13 Effect of Concrete Strength on the General Method (Yoon)

58

5.14 Details of Beam Specimens and Instrumentation (Sarsam,1992)

59

5.15 Effect of the Ratio of Shear span on the Shear Friction Method (Sarsam)

62

5.16 Effect of the Ratio of Shear span on the Simplified Method (Sarsam)

63

5.17 Effect of the Ratio of Shear span on the General Method (Sarsam)

63

5.18 Effect of Concrete Strength on the Shear Friction Method (Sarsam)

64

5.19 Effect of Concrete Strength on the Simplified Method (Sarsam)

65

5.20 Effect of Concrete Strength on the General Method (Sarsam)

65

x

5.21 Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the Shear Friction Method (Sarsam)

66

5.22 Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the Shear Friction Method (Sarsam)

67

5.23 Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the Simplified Method (Sarsam)

67

5.24 Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the Simplified Method (Sarsam)

68

5.25 Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the General Method (Sarsam)

68

5.26 Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the General Method (Sarsam)

69

5.27 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement on the Shear Friction Method

(Sarsam)

70

5.28 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement on the Simplified Method (Sarsam)

70

5.29 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement on the General Method (Sarsam)

71

5.30 Predicted Results by the Shear Friction Method (with stirrups)

80

5.31 Predicted Results by the Simplified Method (with stirrups)

81

5.32 Predicted Results by the General Method (with stirrups)

82

5.33 Effect of the Ratio of Shear Span on the Shear Friction Method (with

stirrups)

84

5.34 Effect of the Ratio of Shear Span on the Simplified Method (with stirrups)

85

5.35 Effect of the Ratio of Shear Span on the General Method (with stirrups)

85

5.36 Effect of Concrete Strength on the Shear Friction Method (with stirrups)

86

5.37 Effect of Concrete Strength on the Simplified Method (with stirrups)

86

5.38 Effect of Concrete Strength on the General Method (with stirrups)

87

5.39 Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the Shear Friction Method (with stirrups)

87

5.40 Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the Simplified Method (with stirrups)

88

5.41 Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the General Method (with stirrups)

88

5.42 Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the Shear Friction Method (with stirrups)

89

5.43 Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the Simplified Method (with stirrups)

89

5.44 Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the General Method (with stirrups)

90

5.45 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement on the Shear Friction Method (with

stirrups)

90

xi

5.46 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement on the Simplified Method (with

stirrups)

91

5.47 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement on the General Method (with stirrups)

91

5.48 Effect of Beam Depth on the Shear Friction Method (with stirrups)

92

5.49 Effect of Beam Depth on the Simplified Method (with stirrups)

92

5.50 Effect of Beam Depth on the General Method (with stirrups)

93

5.51 Predicted Results by the Shear Friction Method (without stirrups)

95

5.52 Predicted Results by the Simplified Method (without stirrups)

96

5.53 Predicted Results by the General Method (without stirrups)

97

5.54 Effect of the Ratio of Shear Span on the Shear Friction Method (without

stirrups)

99

5.55 Effect of the Ratio of Shear Span on the Simplified Method (without stirrups)

99

5.56 Effect of the Ratio of Shear Span on the General Method (without stirrups)

100

5.57 Effect of Concrete Strength on the Shear Friction Method (without stirrups)

100

5.58 Effect of Concrete Strength on the Simplified Method (without stirrups)

101

5.59 Effect of Concrete Strength on the General Method (without stirrups)

101

5.60 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement Ratio on the Shear Friction Method

(without stirrups)

102

5.61 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement Ratio on the Simplified Method

(without stirrups)

102

5.62 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement Ratio on the General Method

(without stirrups)

103

5.63 Effect of Longitudinal Reinforcement Strength on the General Method

(without stirrups)

103

5.64 Effect of Beam Depth on the Shear Friction Method (without stirrups)

104

5.65 Effect of Beam Depth on the Simplified Method (without stirrups)

104

5.66 Effect of Beam Depth on the General Method (without stirrups)

105

xii

NOTATION

a

shear span, distance from centre of support to point load

a

clear shear span, distance between outer edge of plate for concentrated

c

load and inner edge of plate at support

A

area of potential shear failure plane

A

area of longitudinal reinforcement in tension zone

A

area of one stirrup

s

v

b

width of beam web

c

coefficient of the cohesion between a potential shear failure plane

Cb

concrete cover at top of beam

c,

concrete cover at bottom of beam

C

concrete strength of beam

w

C

factored concrete strength of beam

C. O. V.

coefficient of variation

r

d

distance from the extreme compression fibre to the centroid of the

longitudinal tension reinforcement

d

diameter of a reinforcing bar

d

distance measured perpendicular to the neutral axis between the resultants

b

v

of the tensile and compressive forces due to flexure

d

effective length of stirrup in the shear friction method

fry

specified yield strength of the stirrups

f

specified yield strength of the longitudinal reinforcement or stirrups

ev

y

f'

specified compressive concrete strength

h

overall height of member

k

factor for relating shear strength and normal stress determined from

c

experiments

n

number of stirrups crossed by a potential shear failure plane

R

normal force acting on potential shear failure plane

xiii

5

spacing of stirrups

S

shear force on potential shear failure plane

T

longitudinal reinforcement strength of beam

T

opi

force in longitudinal reinforcement for peak shear strength

T

r

factored longitudinal reinforcement strength of beam

T

v

tension force in a stirrup

T

vr

factored tension resistance in a stirrup

v

average shear stress on potential shear failure plane according to Loov's

equations

V

factored shear resistance attributed to the concrete

V

factored shear resistance attributed to the concrete for the C S A general

c

cg

method

V f

CS

factored shear resistance attributed to the concrete for the shear friction

method

V

dowel force in the longitudinal reinforcement

Vf

factored shear force at section

d

V

shear resistance of beam using C S A A23.3-94 general method

V

factored transverse component of prestress of beam

V

factored shear resistance of beam

V

rg

factored shear resistance of beam using C S A A23.3-94 general method

V

s

factored shear resistance provided by the shear reinforcement

Vf

factored shear resistance for the shear friction method

V

factored shear resistance provided by the stirrups for the C S A general

g

p

r

s

sg

method

V

sim

shear resistance of beam using C S A A23.3-94 simplified method

V

s¡

shear resistance provided by one stirrup

Vf

factored shear resistance attributed to the reinforcement for the shear

ss

friction method

xiv

V

ultimate shear resistance of beam measured from test

V

shear resistance of concrete on a 45° plane

a

angle between transverse reinforcement and the shear plane

a/

angle between shear friction reinforcement and longitudinal axis

(8

factor that depends on the average tensile strains in the cracked concrete

t

4S

using C S A general method

j3

calibration factor for shear friction method

6

angle between longitudinal axis and potential shear failure plane

v

9

minimum shear failure angle for the shear friction method

X

factor to account for low density concrete

\i

coefficient of friction

p

longitudinal tension reinforcement ratio

p

transverse reinforcement ratio

o

average normal stress on potential shear failure plane

min

v

<j)

resistance factor for concrete

¢¡.

resistance factor for reinforcement

y/

factor that depends on the ratio of longitudinal reinforcement strength to

c

optimum tension for the shear friction method

xv

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 General

Failure in shear of reinforced concrete takes place under combined stresses

resulting from an applied shear force, bending moments and, where applicable, axial

loads and torsion as well. Because of the non-homogeneity of material, non-uniformity

and non-linearity in material response, presence of cracks, presence of reinforcement,

combined load effects, etc., the behavior of reinforced concrete in shear is very

complicated, and the current understanding of and design procedures for shear effects are

based on analyses of results of extensive tests and simplifying assumptions rather than on

an exact universally acceptable theory.

The best-known model for the expression of the behavior of beams with web

reinforcement failing in shear is the truss model. The truss model is a helpful tool to

visualize the nature of stresses in the stirrups and in the concrete, and to base simplified

design concepts and methods on. It may also be used to derive equations for the design of

shear reinforcement. However, it does not recognize fully the actual action of web

reinforcement and its effect on the various types of shear transfer mechanisms.

A shear-friction model has been developed to predict the shear strength of beams

by Loov

( 1 7 ) ( 1 8 ) ( I 9 )

and many others O W i X W M W W W S ) . Because shear friction works well

for composite beams, it might also predict the shear strength of beams which also have

potential

major

cracks

along which

slip can occur. Stirrups and longitudinal

reinforcement provide a clamping force thereby increasing the friction force which can be

transferred across a crack along a potential failure plane. This model is based on the shear

strength after cracking so that no diagonal tension strength is included. In this thesis, the

shear friction model has been investigated and developed for the purpose of shear design

of beams.

2

1.2 Code Review

Prior to its 1984 revision, C S A Standard A23.3 recommended a method for shear

and torsion design based on the traditional method adopted by the A C I code.

The

procedure is called the "V + V" approach. The term V is referred to as the "shear carried

c

c

by the concrete", while the term V is referred as the "shear carried by the stirrups". A23.3

s

assumes that V is equal to the shear strength of a beam without stirrups and further

c

simplifies V to equal the shear at inclined cracking. V relies on the tensile strength of the

c

s

transverse reinforcement. The stirrups and the inclined compressive struts are assumed to

act as members of a 45-degree truss and the term V is calculated based on this model.

s

The 1984 revision of the Canadian Standard, C A N 3 A23.3-M84, recommended

two alternative methods for shear design.

The first of these, termed the "simplified

method" (CAN3 A23.3-M84 (11.3)) is a shortened version of the traditional method

followed by A C I and previous Canadian codes. In the simplified method, the transverse

reinforcement is designed for the combined effect of shear and axial load i f any, while the

longitudinal reinforcement is designed for the combined effect of flexural and axial load.

The second method is termed as "general method" for shear design (CAN3

A23.3-M84(l 1.4)). In this method, the truss analogy has been used in a more direct

manner to account for the influence of diagonal tension cracking on the diagonal

compressive strength of concrete, and the influence of shear on the design of longitudinal

reinforcement. The code requires that deep beams, parts of members with deep shear

span, brackets and corbels, and regions with abrupt changes in cross-section (such as

regions of web openings in beams) be designed by the general method only. But we will

find later in this thesis that the general method is not suited to the design of deep beams,

brackets and corbels.

C S A Standard A23.3-94 recommends three alternative methods for shear design.

Regions of members in which it is reasonable to assume that plane sections remain plane

shall be proportioned for shear and torsion using either the general method or the

simplified method (if member is not subjected to significant axial tension) or the strut-

3

and-tie model. Regions of members in which the plane section assumption of fiexural

theory is not applicable shall be proportioned for shear and torsion using the strut-and-tie

model.

The simplified method of shear design described in C S A Standard A23.3-94 is

not simple. The designer is required to check numerous equations and limits. On the other

hand, the general method is extremely complex so engineers rarely use it in engineering

practice.

1.3 Scope of Study

The main objective of this study is to introduce the shear-friction method for

engineering design. After reviewing shear design theories and shear design methods

which are used by recent C S A Standard A23.3-94, a method of shear design based on

shear friction theories has been applied to predict the shear capacity of reinforced

concrete beams.

A comparison of the shear-friction method and recent code methods with the test

results of beams from the literature has been presented in this thesis. Proposed code

clauses for shear design based on the shear-friction method have been developed and

design examples based on the shear friction method are also included in this thesis.

1.4 Thesis Organization

Chapter 2 contains the review of basic shear theories. The factors of shear

strength are listed and shear failure mechanisms and modes are discussed in this chapter.

In Chapter 3 C S A Standard A23.3-94 for shear design has been introduced and

the design methods have been discussed.

Chapter 4 introduced the shear friction methods by Loov and others. In Chapter 5

a modified equation of the shear friction method has been introduced and a comparison of

the shear-friction method and recent code methods with the test results of beams from the

literature has been presented in this chapter.

4

Proposed code clauses for shear design based on the shear-friction method with

design examples have been put in Chapter 6. Conclusions and recommendations are

given in Chapter 7.

5

CHAPTER 2

B A S I C S H E A R THEORIES

2.1 Homogeneous Beam

In order to gain an insight into the causes of shear failure in reinforced concrete,

the stress distribution in a homogeneous elastic beam of rectangular section will be

reviewed briefly. From the free-body diagram as shown in Fig.2-1, it can be seen that

Where

dM = the bending moment change from section to section

dx = the distance between sections

V = the shear force on the section

M+dM

Fig. 2-1, Internal Forces in Beam

By the traditional theory for homogeneous-elastic-uncracked beams, the shear

stresses, v, and the flexural stress, f , at a point in the section distant y from the neutral

x

axis are given by

(2-2)

6

(2-3)

Where

Q = the first moment about the neutral axis of the part of the cross-sectional

area above the depth y

I - the moment of inertia of the cross section

b = the width of the beam

The distribution of these stresses is as shown in Fig. 2-2. Considering an element

at depth y (Fig. 2-3), the fiexural and shear stresses can be combined using Mohr's circle

into equivalent principal stresses, f¡ and f , acting on orthogonal planes inclined at an

2

angle a, where

ÍZ7

i

f

u

~

2

f

x

±

Í{2

f

(2-4)

x

and

(2-5)

tan(2«) = —

Fig. 2-2, Distribution of Fiexural Shear Stresses

Fig. 2-3, Principal Stresses

The principal stress trajectories in the uncracked beam are plotted in Fig. 2-4a.

Stress trajectories are a set of orthogonal curves, whose tangent at any point is in the

direction of the principal stress at that point. The compressive stress trajectories are steep

near the bottom of the beam and flatter near the top.

In concrete, which is weak in

tension, tensile cracks would occur at right angles to the tensile stresses and hence the

compressive stress trajectories indicate potential crack patterns (see Fig.2-4b). (Note that

if in fact a crack is developed, the stress distributions assumed here are no longer valid in

that region and redistribution of the internal stresses takes place.) The location of the

absolute maximum principal tensile stress will depend on the variation off and v, which

x

in turn depends on the shape of the cross section and on the span and loading.

It is seen that the general influence of shear is to induce tensile stresses on an

inclined plane. Failure of concrete beams in shear is triggered by the development of

these inclined cracks under combined stresses. To avoid a failure of the concrete in

compression, it is also necessary to ensure that the principal compressive stress,/^, is less

than the compressive strength of concrete under the biaxial state of stress.

Fig. 2-4a, Stress Trajectories

Fig. 2-4b, Potential Crack Pattern

9

Although several theories of failure have been used for concrete shear design, for

the traditional method of shear and torsion design, the principal tensile stress theory has

been followed.

2.2 Beam Cracking Modes

The cracking pattern in a test beam is shown in Fig.2-5. Two types of cracks can

be seen. The vertical cracks occurred first, due to fiexural stresses. These start at the

bottom of the beam where the fiexural stresses are the largest. The inclined cracks at the

ends of the beam are due to combined shear and flexure. These are commonly referred to

as inclined cracks or shear cracks. Such cracks must exist before a beam can fail in shear.

Several of the inclined cracks have extended along the reinforcement toward the support,

weakening the anchorage of the reinforcement.

Fig. 2-5, A Cracked Beam without Shear Reinforcement (Ref. 27)

Although there is a similarity between the planes of maximum principal tensile

stresses and the cracking pattern, fiexural cracks generally occur before the principal

tensile stresses at midheight become critical. Once such a crack has occurred, the

10

principal tensile stresses across the crack drops to zero. To maintain equilibrium, a major

redistribution of stresses is necessary. As a result, the onset of inclined cracking in a

beam cannot be predicted from the principal stresses unless shear cracking precedes

flexural cracking. This very rarely happens in reinforced concrete but does occur in some

prestressed beams (such as I-section beam).

The cracking pattern in a test beam with shear reinforcement is shown in Fig.2-6.

It is obvious that inclined cracks are almost straight lines instead of curves that we have

seen in the test beam without shear reinforcement in Fig.2-5. Another evidence we can

see is that inclined cracks bypass as many stirrups as possible. These evidences are useful

to predict possible beam shear failure planes.

Fig. 2-6, A Cracked Beam with Shear Reinforcement (Ref. 35)

2.3 Shear Transfer Mechanisms

There are several mechanisms by which shear is transmitted between two planes

in a concrete member. Fig. 2.7 shows a free body of one of the segments of a reinforced

concrete beam separated by an inclined crack. The major components contributing to the

shear resistance are:

11

(1) The shear strength, V , of the uncracked concrete;

cz

(2) The vertical component, V^, of the aggregate interlock shear, V ;

a

(3) The dowel force, V , in the longitudinal reinforcement;

d

(4) The shear, V , carried by the shear reinforcement.

s

Fig. 2-7, Internal Forces in a Cracked Beam

The aggregate interlock, V , is a tangential force transmitted along the plane of the

a

crack, resulting from the resistance to relative movement (slip) between the two rough

interlocking surfaces of the crack, much like frictional resistance and transverse rebar

dowel effects. So long as the crack is not too wide, the force V may be very significant.

a

The dowel force in the longitudinal tension reinforcement is the transverse force

developed in these bars functioning as a dowel across the crack, resisting relative

transverse displacements between the two segments of the beam.

12

Each of the components of this process except V has a brittle load-deflection

s

response. So it is difficult to quantify the contributions of V , V¿¡, and V . In design,

cz

ay

these are lumped together as V , referred to as "the shear carried by the concrete". Thus

c

the nominal shear strength, V , is assumed to be

n

V =V +V

n

c

(2-6)

s

In North American design practice, V is traditionally taken equal to the failure

c

capacity of a beam without stirrups.

2.4 Shear Failure Modes

2.4.1 Beam without Shear Reinforcement

In beams without shear reinforcement, the breakdown of any of the shear transfer

mechanisms may lead to failure. In such beams there are no stirrups enclosing the

longitudinal bars and restraining them against splitting failure and the value of V is

d

usually small. The component V

ay

also decreases progressively due to the unrestrained

opening up of the crack. The spreading of the crack into the compression zone decreases

the area of uncracked concrete section contributing to V .

cz

However, in relatively deep

beams (a/d < 1), tied-arch action may develop following inclined cracking (see Fig. 2-9

(b)), which in turn will transfer part or all of the shear load at the section directly to the

supports thereby the shear capacity of the beam does not totally rely on V

ay

and V .

cz

Because of the uncertainties in all these effects, it is difficult to predict precisely the

behavior and strength beyond diagonal cracking of beams without shear reinforcement.

In beams without shear reinforcement, the shear failure load may equal or exceed

the load at which inclined cracks develop, depending on several variables such as the

ratio M/(Vd), thickness of web, influence of vertical normal stresses, concrete cover and

resistance to splitting (dowel) failure. Further, the margin of strength beyond diagonal

cracking fluctuates considerably.

Hence, for beams of normal proportions (M/(Vd) >

about 2.5), as a design criterion, the shear force, V , causing the formation of the first

cr

13

inclined crack is generally considered as the usable ultimate strength for beams without

shear reinforcement.

The moments and shears at inclined cracking and failure of rectangular beams

without web reinforcement are plotted as a function of the shear span, a, to the depth, d,

in Fig.2-8. The shaded areas in this figure show the reduction in strength due to shear, so

web reinforcement has to be provided to ensure that the full fiexural capacity can be

developed.

Typical shear failure modes of reinforced concrete beams, and the influence of the

a/d ratio, are illustrated in Fig. 2-9 with reference to a simply supported rectangular beam

subjected to symmetrical two-point loading.

In very deep beams (a/d < 1) without web reinforcement, inclined cracking

transforms the beam into a tied-arch (Fig. 2-9b).

The tied-arch can fail by either a

breakdown of its tension element, or by a breakdown of the concrete compression chord

by crushing.

In relatively short beams, with a/d in the range of 1 to 2.5 (Fig. 2-9c), the failure

is initiated by an inclined crack, usually a flexural-shear crack. The actual failure may

take place by crushing of the reduced concrete section above the head of the crack under

combined shear and compression, or cracking along the tension reinforcement resulting

in loss of bond and anchorage of the tension reinforcement. This type of failure usually

occurs before the fiexural strength of the section is attained.

Normal beams have a/d ratios in excess of about 2.5. Such beams may fail in

shear or in flexure. The limiting a/d ratio above which fiexural failure occurs depends on

the tension reinforcement ratio, yield strength of reinforcement and concrete strength.

V

v

a

a

(a) Beam.

Deep

*

H

Slender

Very.Shorty

short

c

1

re

^¾¾^

c

Failure

03

O

E

o

,

y / A / e r y slender

" ' V

1

/

/

/

/

^ ^ C ^

^

^ s ^ ^

^

^

Flexural capacity

Inclined cracking

and failure

^*».

2

•

1.0

Inclined

cracking

i

2.5

6.5

a/d

(b) Moments at cracking and failure.

<T3

C>t

Flexural capacity

JO

CO

nclined cracking and failure

1.0

2.5

6.5

a/d

(c) Shear at cracking and failure.

Fig. 2-8, Effect of a/d on Shear for Beams Without Shear Reinforcement (Ref. 27)

15

i

(a)

Shear-tension failure

( )

c

Diagonal tension failure

l«a/d<2

5

Shear-compression failure

(d) 2.5 < a / d < * * 6

T

( e ) Web-crushing failure

Fig. 2-9, Shear Failure Modes (Ref. 36)

16

For beams with a/d ratios in the range of 2.5 to 6, fiexural tension cracks develop

early on; however, before the ultimate fiexural strength is reached the beam may fail in

shear by the development of inclined flexure-shear cracks, which, in the absence of web

reinforcement, rapidly extend right through the beam as shown in Fig. 2-9d. This type of

failure is usually sudden and without warning and is termed diagonal-tension failure.

Addition of web reinforcement in such beams leads to a shear-compression failure or a

fiexural failure.

In addition to these different modes, thin webbed members such as I-beams with

web reinforcement may fail by crushing of the concrete in the web portion between

inclined cracks under the diagonal compression forces (Fig. 2-9e).

2.4.2 Beam with Shear Reinforcement

In members with shear reinforcement the shear resistance continues to increase

even after inclined cracking until the shear reinforcement yields and V can increase no

s

more. Any further increase in applied shear force leads to increases in V , V , and V^.

cz

d

With progressively widening crack width (which is no longer restrained because of

yielding of the shear reinforcement),

begins to decrease forcing V and V to increase

cz

d

at a faster rate until either a splitting (dowel) failure occurs, or the concrete in the

compression zone fails under the combined shear and compression forces.

Thus, in

general, the failure of shear-reinforced members is more gradual (ductile).

2.5 Factors Affecting the Shear Strength

2.5.1 Tensile Strength of Concrete

The inclined cracking load is a function of the tensile strength of the concrete.

The stress state in the web of the beam involves biaxial principal tension and

compression stresses as discussed before. A similar biaxial state of stress exists in a split

cylinder tension test and the inclined cracking load is frequently related to the strength

from such test.

17

2.5.2 Longitudinal Reinforcement

Fig. 2-10 shows the shear capacities of simply supported beams without stirrups

as a function of the steel ratio, p. When the steel ratio, p, is small, flexural cracks extend

higher into the beam and open wider, as a result inclined cracking occurs earlier and the

beam shear strength tends to be lower.

2.5.3 Shear Span-to-depth Ratio, a/d

As discussed earlier, the shear span-to-depth, a/d, has effects on the inclined

cracking shears and ultimate shears of "deep" beam, while for longer shear spans with a/d

greater than 3 it has little effect on the inclined cracking shear.

0.005

0.010

0.015

0.020

0.025

0.030

0.035

Fig. 2-10, Shear Strength vs. Longitudinal Reinforcement (Ref. 27)

0.040

Fig. 2-11, Shear Strength vs. a/d (Ref. 14)

19

2.5.4 Size of Beam

As the overall depth of a beam increases, the shear stress at inclined cracking

tends to decrease for a given f' , p, and a/d. As the depth of the beam increases, the

c

crack widths at points above the main reinforcement tend to increase. This leads to a

reduction in aggregate interlock across the crack, resulting in earlier inclined cracking. In

beams with web reinforcement the web reinforcement holds the crack faces together so

that the aggregate interlock is not lost as much as that of beams without web

reinforcement.

Fig. 2-12, Influence of Member Size on Shear Strength (Ref. 7)

20

2.5.5 Axial Forces

Axial tensile forces tend to decrease the inclined cracking load, while axial

compressive forces tend to increase it. As the axial compressive force is increased, the

onset of fiexural cracking is delayed and the fiexural cracks do not penetrate as far into

the beam. So a larger shear is required to cause principal tensile stresses equal to the

tensile strength of the concrete.

•

•

_

••

Vu

•

^Fcbwd

-

Eq. 6 - 1 7 a

/

(ACI Eq. 11-4)

1500

1000

•

•

-/-—

^**"

Eq. 6 - 1 7 b

(ACI Eq. 11-8)

500

Compression

A x i a l stress, NJA

g

(psi)

Fig. 2-13, Effect of Axial Loads in Inclined Cracking Shear (Ref. 27)

2.5.6 Web Reinforcement

Prior to inclined cracking, the strain in the stirrups is equal to the corresponding

strain of the concrete. Since concrete cracks at a very small strain, the stress in the

stirrups prior to inclined cracking will be very small. Thus stirrups do not prevent

inclined cracks from forming. They come into play only after the cracks have formed.

Following the development of inclined cracking, stirrups intercepted by the cracks

resist a portion of the shear. The web reinforcement contributes significantly to the

21

overall shear strength by the direct contribution of V to the shear strength. Secondly, web

s

reinforcement crossing the inclined cracks restricts the widening of the crack and thereby

helps maintain the aggregate interlock resistance of shear. The web reinforcement also

can improve the longitudinal tension reinforcement dowel action and provide another

dowel action of itself crossing inclined cracks.

Flexural

cracking

Inclined

cracking

Yield of

stirrups

Failure

Applied shear

Fig. 2-14, Distribution of Internal Shears of Beam with Shear Reinforcement (Ref. 27)

22

CHAPTER 3

S H E A R DESIGN - C S A S T A N D A R D A23.3-94

3.1 General

The C S A Standard A23.3-94 recommends two alternative methods for shear

design. The "Simplified Method" is a short version of the traditional method followed by

A C I and previous Canadian Codes. In the Simplified Method, a 45-degree truss model

has been used and the transverse reinforcement is designed based on that.

The second method is the "general method" for shear design. In this method, the

truss analogy has been used in a more direct manner to account for the influence of

diagonal tension cracking on the diagonal compressive strength of concrete, and the

influence of shear on the design of longitudinal reinforcement.

Both simplified method and general method are sectional methods and can be

applied only to the flexural region of beams, in which it is reasonable to assume that

plane sections remain plane and that shear stresses are distributed in a reasonably uniform

manner over the depth of the beam. Because of this, both methods are not appropriate for

regions of members near static or geometric discontinuities, the code requires regions

with abrupt changes in cross-section (such as regions of web openings in beams) and

brackets and corbels, to be designed by the strut-and-tie method, which is capable of

more accurately modeling the actual flow of forces in these regions.

3.2 Simplified Method

For flexural members not subjected to significant axial tension, the Canadian code

allows shear design based on the simplified method.

Required shear resistance for beam is:

V >V,

r

(3-1)

23

Where Vf is the factored shear force at a section, and V is the sum of the

r

contribution attributed to the concrete and transverse reinforcement.

V = V + V,

r

(3-2)

c

But V is limited to:

r

V,iV +0.8ty JfJb d

e

e

(3-3)

w

This upper limit is intended to ensure that the stirrups will yield prior to crushing

of the web concrete and that diagonal cracking at specified loads is limited.

3.2.1 Shear Supported by Concrete, V

c

V =0.2ty Jf¡b d

c

e

(3-4)

w

This equation can be used only for beams with minimum transverse reinforcement

given by Clause 11.2.8.4 i f ^exceeds 0.5 V + <j) V :

c

p

p

A =0.06jf ^f

v

(3-5)

c

J V

The minimum transverse reinforcement restrains the growth of inclined cracking

and increases ductility to provide a warning of failure.

For beams without transverse reinforcement, Clause 11.3.5.2 shall be used to

account for the reduced strength of beams deeper than 300 mm.

24

V,

260

1000+ d

(3-6)

At Jfìb d>0.lA&4fÌb d

c

w

w

Studies have shown that the equations for V above are more appropriate for

c

beam with a/d ratios greater than three. It results in overly conservative design for beams

with a/d ratios less than 2.5 (see Fig. 3-1).

0.30

|«

a

0.25

»|

|——a

»»j

//.illi.l

f

0.20

Clause 11.5:

Strut-and-tie model

bdf,

-

610mm

•

f ' = 27.2 MPa

c

max. agg. = 19 mm

0.15

d = 538 mm

Experimental

result

b= 155 mm

0.10

A, = 2277 m m

Clause 11.4:

Sectional model

r = 3 7 2 MPa

y

A =0

v

0.05

3

4

a/d

Fig. 3-1, Comparison of Shear Design Methods and Test Results (Ref.7)

2

25

3.2.2 Shear Supported by Stirrups, V

s

<l> Avf d

s

y

(3-7)

s

Here the transverse reinforcement is assumed to be perpendicular to the

longitudinal axis of the member.

Additional

maximum spacing (Clause

11.2.11) and minimum transverse

reinforcement requirement (Clause 11.2.8) have been patched onto the basic equation in

order to obtain satisfactory behavior under various conditions.

3.3 General Method

Shear resistance for beam is:

(3-8)

Where V

cg

is the factored shear resistance contributed by concrete at a section,

and V is the factored shear resistance contributed by transverse reinforcement.

sg

But V„ shall not exceed

V = 0.25

c

Áfcf¿b d

w

v

(3-9)

Where d is the distance measured perpendicular to the neutral axis between the

v

resultants of the tensile and compressive forces due to flexure, but need not be taken less

than 0.9d.

This upper limit is intended to ensure that the stirrups will yield prior to crushing

of the web concrete and that diagonal cracking at specified loads is limited.

26

3.3.1 Shear Supported by Concrete, V

V =UA&ft

cg

4f!b d

c

w

(3-10)

v

Where p is determined in accordance with Clause 11.4.4.

3.3.2 Shear Supported by Stirrups, V

sg

S

Where 0is given in Clause 11.4.4. Obviously i f 0 = 45° both simplified method

and general method will have the same shear resistance contributed by transverse

reinforcement. Again assume that the transverse reinforcement is perpendicular to the

longitudinal axis of the member.

For members with transverse reinforcement inclined at an angle a to the

longitudinal axis, V shall be computed from

sg

_

faA f d (cot0

v y

v

+ cota)sina

27

CHAPTER 4

S H E A R D E S I G N - S H E A R FRICTION M E T H O D

4.1 General

The Clause 11.1.3 in C S A Standard A23.3-94 states that shear friction shall be

used to design "Interfaces between elements such as webs and flanges, between

dissimilar materials, and between concrete cast at different times or at existing or

potential major cracks along which slip can occur..." Because beam shear failure

normally comes with a major crack and slip between the crack, it would seem that shear

friction can also be applied to predict the shear strength of beams. In 1997, Loov

(19)

presented the rudiments of a procedure , which applied this concept to the shear design

of beam. In recent years, Loov, Peng, Tozser, Kriski, and others, have shown that it is

possible to use a simpler method for shear design that is based on the shear friction

theory.

(16)(17)(18)(21)(23)(24){25)(26)(35)

It is encouraging that some of the resulting equations

derived by Loov match those equations derived by a number of people, including

(5)

Braestrup , Nielsen

(33)

and Zhang

(45)

based on theories of plasticity.

4.2 General Equations for Beam Shear Based on Shear Friction:

The shear-friction concept for concrete-to-concrete interfaces is based on the

assumption that a crack will form and shear will be transferred across the interface

between the two parts that can slip relative to one another. If the crack faces are rough

and irregular, this slip is accompanied by separation of the crack faces. The separation

will stress the reinforcement crossing the crack until the reinforcement reaches its yield

point. Thus the reinforcement provides a clamping force across the crack interface.

28

Shear displacement

t î t î î t î 1111

Compression

in concrete = T

(i) Shear Tension Causing Crack Opening

i

Shear stress

Tension in

reinforcement = T

(ii) Free-Body-Diagram

Fig. 4-1, Shear Friction Concept (Ref.7)

4.2.1 Shear Friction Strength:

There are many equations that have been developed for predicting shear friction

strength.

Fig.4-1 illustrates the

shear

friction

concept for the case where the

reinforcement is perpendicular to the potential failure plane. Because the interface is

rough, shear displacement will cause a widening of the crack. This crack opening will

cause tension in the reinforcement balanced by compressive stresses, a, in the concrete

across the crack. The shear resistance of the face is often assumed to be equal to the

cohesion, c, plus the coefficient of friction, ju, times the compressive stress, a, across the

face. That is,

v =À&(c+Mff)

(4-1)

r

If inclined reinforcement is crossing the crack, part of the shear can be directly

resisted by the component, parallel to the shear plane, of the tension force in the

reinforcement. See Fig.4-2. Clause 11.6 of C S A Standard A23.3-M94 suggests that the

factored shear stress resistance of the shear plane shall be computed as:

v =A,fc(c+fia)+ûp fcosa/

r

v

(4-2)

29

Where a is the angle between the shear friction reinforcement and the shear

f

plane.

\ \ \

Fig. 4-2, Reinforcement Inclined to Potential Failure Cracks (Ref.7)

C S A Standard A23.3-M94 also gives an alternative equation for shear friction

strength, which is based on the work of Loov and P a t n a i k

(20)(22)

.

(4-3)

Where

& = 0.5 for concrete placed against hardened concrete

k = 0.6 for concrete placed monolithically.

In this method, the shear resistance is a function of both the concrete strength and

the amount of reinforcement crossing the failure crack. Fig. 4-3 shows how this equation

compares with the results from various push-off tests.

a Mattock (uncracked)

• Mattock (cracked)

A Walraven (cracked)

v/0~fHMPa)

Fig. 4-3, Push-off Test Results (Ref.22)

31

Fig. 4-4 shows a free body diagram of the end portion of a simple beam with

loads applied somewhere to the right of the section. Two equilibrium equations relate the

normal force, R, and the shear force, S, to T, the force in the main tension reinforcement,

nT , the total force in the stirrups crossing the plane and V, the end reaction. The forces

v

on a potential failure plane vary with the angle 0 between the axis of the beam and the

plane. When the loads between the reaction and the plane in question are negligible, then

V is equal to the vertical shear on the inclined plane.

R = Tsin0-(V-ZT )cosd

n

(4-4)

S = Tcos0-(V-ZT )sin0

(4-5)

v

v

32

Where T = Af

y

and T = AJ^. Here A is the area of longitudinal reinforcement

v

s

and f is its yield strength, while A is the total area of all legs of a stirrup and f

y

v

vy

is the

stirrup yield strength.

Using the relationship from Eq. 4-3, the shear friction stress is

v=

kjtf

(4-6)

While

R

and

a =

Where A is the area of the inclined failure plane,

A=

bh

w

(4-7)

sine?

Where b is the width of web, h is the total depth, and 6 is the angle between the

w

longitudinal reinforcement and the crack.

The shear force is therefore proportional to the square root of the normal force, R

S = k4Rf^4

(4-8)

The equations shown above (Eq. 4-4 to Eq. 4-8) can be combined to give a

general equation for the shear strength

2

V = 0.5k C

2

2

0.25 k C

+ cot

0-cotO (1 + cot 6)-Tcot0

2

+ Yjv

4

9

(")

Where

C -

f'Xh

(4-10)

33

This equation is similar to that derived by Braestrup

( 5 )

and by Nielsen

( 3 3 )

with

plasticity theory.

For design, the factored values should be used thus

2

V

r

2

=0.5k C,

0.25k'C.

• + cot

0-cotO (1 + cot 0)-T cot0

2

r

+ J]T

vr

(4-11)

n

Where

(4-12)

(4-13)

T

r=<t>Asfy

T

vr

(4-14)

A

= <t>s vf,y

A l l planes between the inside edge of the support and the edge of the load to a

maximum angle of 90° should be considered to be potential failure planes. The shear

strength on each plane is calculated and the lowest strength, when comparing all possible

failure planes, is the governing shear strength. Under some circumstances it may be

extremely unlikely that a crack will form along particular failure planes so that choosing

the absolute

lowest strength

without regarding to location may be excessively

conservative. This aspect has been investigated by Zhang

( 4 5 )

.

Fig. 4-5 shows the change

in predicted shear strength as the failure plane angle is varied. When a crack intercepts a

stirrup, the shear strength increases by T , the force that can be developed in the stirrup.

v

Fig. 4-6 shows a three-dimensional surface plot, which was obtained by analyzing

beam tests by Kani

( 1 4 )

. The test beams had only one stirrup but in different locations to

determine the effects of stirrup location. The test result shows that it is not necessary to

check every potential failure plane. The planes with the lowest strength have the flattest

possible angle while intersecting a minimum number of stirrups.

Fig. 4-6, Three-dimensional surface of shear strength along all possible failure

planes for beam 544 (Réf. 18)

35

Fig. 4-7 shows a beam with possible critical shear failure planes. Fig. 4-8 is a

photograph of a beam indicating that the actual cracks correspond to the expected failure

planes.

essala

V

T-

Fig. 4-8, A Tested Beam with Critical Shear Cracks (Ref. 35)

B - 7

36

4.2.3 Approximate Shear Capacity of Concrete

If the shear failure plane bypasses the stirrups, the strength along the weakest

plane depends on the longitudinal reinforcement and the angle of the failure plane, but is

unaffected by the stirrup strength. From Eq. 4-9 we can obtain

2

V = 0.5k C

2

2

0.25k C

2

+ cot 6 -cot6 (1 + cot

(4-15)

0)-Tcot6

Beams depend on longitudinal reinforcement and the anchorage of longitudinal

reinforcement to develop shear capacity. The optimum tension in the longitudinal

reinforcement, by which the maximum shear capacity will be developed, can be obtained

by differentiating Eq. 4-15

2

dV

(l + cot 6)

— - = . '

c

/

2

dT

=-cotO

(4-16)

2

4t /0.25k C +cot 0

2

T

opt

(4-17)

2

= 0.25k C(2 +tan 6)

Substitute Eq. 4-17 into Eq. 4-15, the shear strength of beams will be

V = 0.25k''Ctond

(4-18)

c

Eq.4-18 gives the shear capacity of beams with longitudinal reinforcement tension

capacity f A

y

s

>T

2

opt

2

- 0.25k C(2+tan

9). It is assumed that anchorage for longitudinal

reinforcement to develop such tension capacity is sufficient.

Fig. 4-9 shows VjC

vs.cot# for different ratios of longitudinal reinforcement. It

is clear that Eq. 4-8 represents the upper bound value of shear capacity of beams. For

beams with longitudinal reinforcement tension capacity less than T t> the ^

op

longitudinal reinforcement tension capacity, the less the shear capacity.

e s s

the

37

0.50

0.40

0.30

>

0.20

0.10

0.00

Fig. 4-9, Shear Strength vs. cotO

For beams with longitudinal reinforcement tension capacity f A

y

s

less than Jopt,

Eq. 4-15 can be substituted approximately by a simple equation as following:

2

V, = 0.25k sin

\

n T

2T

°t* J

Ctand

(4-19)

38

Fig. 4-10, Shear Strength vs. cotO by Eq. 4-15 and Eq. 4-19

The curves from Eq. 4-15 and Eq. 4-19 have been plotted on Fig. 4-10 for

comparison. The graph shows that Eq. 4-19 is a useful approximation for the shear

capacity of concrete.

For factored design, we should use:

2

V

cr

= 0.25 k C tane

r

2

V„ = 0.25k sin

n T

C tan6

r

2T

V

°p>

When

T>Topt

(4-20)

When

T<Tapt

(4-21)

J

Where

(4-22)

39

T = <t> AJ

s

T

opt

(4-23)

y

2

= 0.25k C (2

r

2

+ tan 9)

(4-24)

Fig. 4-11 plots the beam shear strength of concrete vs. the beam longitudinal

reinforcement for a particular plane in the beam based on shear-friction equations of Eq.

4-18 and Eq. 4-19. It shows that the variation of the beam shear strength of concrete

increases as the beam longitudinal reinforcement increases. When the beam longitudinal

2

reinforcement reaches f A

y

s

2

= 0.25k C(2 +tan 9), the beam shear strength of concrete

reaches its peak value and will not increase even though the beam longitudinal

reinforcement increases.

A f (kN)

s

y

Fig. 4-11, Shear Strength vs. Longitudinal Reinforcement of Beam

40

4.2.4 Approximate Shear Capacity of Stirrups

The usual equations for the shear strength of stirrups are overly optimistic. Fig.4-7

shows several possible failure planes with zero, one and two stirrups crossing them. Fig.

4-8 is a photograph of a beam indicating that the actual cracks correspond to the expected

failure planes. To ensure a conservative prediction, the number of stirrups that are

considered to cross the shear plane should be the number of stirrup spaces crossed by the

crack minus one. M a r t i

( 2 8 )

correctly accounted for this in his work. Therefore, because of

the nature of shear failure planes that tend to avoid stirrups the proper estimate of the

stirrup contribution may be

ÚL cote

(4-25)

For factored design, we shall use:

V

y

sr

- V

r

'd cote

}

ev

(4-26)

si

Where

(4-27)

vy

Equation 4-27 is one of the most significant discoveries by M a r t i

( 2 8 )

and Loov

( 1 8 )

in shear design, because this corrects a basic mistake that has been used for years in shear

design.

4.2.5 Approximate Shear Design Equations for Beams with T>T

opt

Using the " V + V " approach, the approximate shear strength along a plane at an

c

s

angle 0 to the beam axis is

41

V =V tanû

r

4S

'décote

+ V

sl

v

s

-1

(4-28)

j

Where

2

V = 0.25k C

4}

(4-29)

r

Further, Eq. 4-31 can be written as:

V =WJ 4TXh

45

(4-30)

v

Where

2

J3 = 0.25k 4/:

(4-31)

V

The coefficients k and fi are calibration factor that can be adjusted to match the

v

equation with test results.

The shear strength of beams without stirrups is governed by the first term in

Equation (4-28), where 0 is the angle of the failure plane with the lowest slope that can

be expected to occur.

V =V tanG

r

45

(4-32)

4.2.6 Critical Shear Failure Angle

Although theoretically we have only an integer number of possible shear failure

planes such as 1, 2 and 3 in Fig. 4-7 and Fig. 4-8, it is convenient to treat Eq. 4-28 as a

continuous function of 6 when deriving the critical shear failure angle. It is notable that

the effects of stirrup spacing will be ignored and Eq. 4-28 will form a lower bound of the

shear capacity, when Eq. 4-28 is considered to be a continuous function of 0 (see Fig. 412).

42

Fig. 4-12, The Shear Contributions of Concrete and Discrete Stirrups (Ref. 18)

The critical angle 0 corresponding to the minimum strength can be found by

differentiating Eq. 4-28.

ñ

—V

d0

r

V

=—½

cos 0

2

V

d

"

=0

sin 0 s

ev

IK,

tane =i^L^-

v

]

a

(4-33)

2

s

Substituted Eq. 4-34 into Eq. 4-28,

(4-34)

43

+v

V. = V45

\v

-i

sl

45

y45

(4-35)

s

So

d„

V =2AV V ^--V

r

45

sl

s¡

(4-36)

Eq. 4-36 is a direct solution for the shear strength of reinforced concrete beams. It

combines the contribution of the web stirrups and concrete corresponding to the

minimum strength of the combination.

From Eq. 4-36 we can solve directly to obtain the maximum stirrup spacing.

s<

(4-37)

(Vf+K,)

2

Eq. 4-37 can be used for design of stirrup spacing, while Eq. 4-36 is used to

calculate the shear capacity of a beam with known stirrup spacing.

Eq. 4-36 and Eq. 4-37 do not apply in cases where the shear failure angle is not

determined by Eq. 4-34. The shear failure crack can only be formed between the beam

support and load, so the beam shear span limits the minimum shear failure angle to:

tanO>

(4-38)

a..

The strength along this steeper plane can be obtained directly using Eq. 4-28.

However, Eq. 4-36 and Eq. 4-37 are conservative i f the shear failure angle becomes

steeper under the limitation of beam shear span.

44

4.2.7 Beams with Longitudinal Reinforcement T <T.opt

For beams without stirrups, the shear capacity can be derived from Equation (421) as following:

K

=yV tanO

When

45

T<Topt

(4-39)

Where

TV T

y/ - sin

(4-40)

2 T

Accordingly, Eq. 4-36 and Eq. 4-37 need to be modified as follows:

V; = 2

\ V V -^-V

s

¥

V

s<

45

sl

(v +v r

f

sl

(4-41)

(4-42)

sl

It is worthy to notice that Eq. 4-41 and Eq. 4-42 may generate conservative results

for beams with short shear span.

45

CHAPTER 5

E X P E R I M E N T A L STUDIES A N D C O M P A R I S O N S

By testing the proposed shear friction method against available experimental

results from different authors, the shear friction method for shear design of beams will be

evaluated in this chapter. A comparison study of the simplified method and the general

method is also conducted in this chapter to choose a more accurate method for shear

strength prediction.

5.1 Application of Shear Friction Method

Using the "V + V" approach as discussed in Chapter 4, the total shear capacity of

c

a beam is:

=V

V

Y

y

sf

csf

T

(5-1)

+V

ssf

y

The shear capacity of concrete, V ^ can be calculated from

cs

(5-2)

Vcs =¥V tane

f

45

Where

(5-3)

=i

w

if/ = sin

tanO =

n T

2T

o

When

T<Topt

(5-5)

(5-7)

y

45

(5-4)

s

*,AJ

T =V (2

T>T,opt

(5-6)

V

4S

T =

When

2

+

tan 0)

(5-8)

46

(5-9)

IT

The value of V / shall be computed from

ss

d„., cot 6

Y

ssf

y

si

-I

(5-10)

Eq. 5-2 is derived from the equation in Chapter 4 with some modifications. The

value of P from Eq.4-37 is:

v

P =0.25k 4fl

2

(5-11)

v

It has been found that k becomes smaller as the concrete strength increases

( 2 2 ) ( 3 7 )

.

The equation found from a least-squares fit of tests is:

k=2.0(/:)-

0

(5-12)

4

Substituted Eq. 5-12 into Eq. 5-11 and get:

/

A

=0.36

\0.30

'30^

\f'c

(5-13)

J

To consider the effects of beam depth as discussed in Chapter 2, Eq. 5-13 needs to

be modified. According to the researches by Tozser and Loov

( 2 5 ) ( 2 6 )

, the shear strength of

025

beams decreases when the depth of beams increases in proportion to h~ . Finally, the

equation for calculating fi is presented by Eq. 5-14.

v

47

0.30

/3 =0.36

V

h

(5-14)

There are two limitations for the cracking angle 0. First, for beams with short

shear spans the shear cracking angle may be limited by the ciç/h ratio as mentioned in

Chapter 4. Second, from pictures of crack patterns of specimens from literature

( 1 4 ) ( 4 5 )

, it

is observed that when the shear span is greater than 2.5, the shear cracking angle 0 stays

at a limiting angle even with increasing shear span. Based on the analysis of the test

results from literature, the minimum shear cracking angle 9 is about 2 i f - ^ / ^ J

degree.

So the two limitations for the failure angle are:

tanO>

(5-15)

6>21 'fit"

\30)

(5-16)

5.2 Test Results in Literature:

Experimental data from the literature were examined to verify whether the shear

friction method is a rational approach for estimating the shear capacity of beams. Tests

from two series of tests from the literature are presented and discussed in detail. The

results predicted by the shear friction method were then compared with the test results

from a total of 113 beams with stirrups and 105 beams without stirrups. A l l selected

beams were simply supported rectangular beams subjected to a symmetrical single or

two-point load. The effects of concrete strength, shear span ratios, amount of longitudinal

reinforcement and stirrup spacing are discussed. Notice that the limitation on maximum

stirrup spacing by the C S A A23.3-94 clauses 11.2.11 for the simplified method and the

general method was ignored during the analysis.

48

5.2.1 Yoon, Cook and Mitchell's Tests, 1996

( 4 4 )

:

Yoon, Cook and Mitchell investigated six full-scale beam specimens

( 4 4 )

. The six

beams having different amounts of shear reinforcement at each end were tested to

provide a total of 12 shear tests. Fig. 5-1 shows the details of the 375 mm wide x 750 mm

deep specimens that were tested with a clear shear span of 2000 mm and shear span ratio

of a/d = 3.28 and a^h = 2.67. The fiexural tension reinforcement for all of the specimens

consisted of 10-No.30 bars in two layers, giving a reinforcement ratio of p = 0.028. A

symmetrical single point load had been applied at midspan. Table 5-1 lists the details of

the beam specimens.

75

11

|350|

1

2000 mm dear

-

150

1—»

1/¾

2150

2150^

5000

y

1

|350i

ELEVATION VIEW

2-No.lO

Strain 9«9e«

on

Stirrup

rwrtforoefnent

vanea

fWNrafONIMflt

r"*""""4

J a/2

LVOT»

on

concreto

10- No 30

cover MOmm

I

SECTION A-À

650

J6JL

INSTRUMENTATION

Fig. 5-1, Details of Beam Specimens and instrumentation (Yoon, Cook and Mitchell)

49

Table. 5-1, Details of Beam Specimens

(,

Shear reinforcement

/ / . Stirrup size and spacing,

MPa

mm

Specimen

36

Comments

8.0 mm diameter at 325

9.5 mm diameter at 465

9.5 mm diameter at 325

0.00

0.35

0.35

0.50

No stirrups

Min /4,, s - d/2

Min A,, s = 0.7d

> Min A,, s = d/2

8.0 mm diameter at 325

0.00

0.35

M-Series:

Ml-S

Ml-N

67

M2-S

M2-N

9.5 mm diameter at 325

9.5 mm diameter at 230

No stirrups

AC1 83, ACI 89,*

CSA 84

Min A^ s = d/2

0.50 CSA 94 min /1,, s = d/2

0.70 ACI 89t mm A,, s < d/2

8.0 mm diameter at 325

0.00

0.35

H-Series:

Hl-S

Hl-N

H2-S

H2-N

87

w

MPa

N-Se ríes:

Nl-S

Nl-N

N2-S

N2-N

b s*

9.5 mm diameter at 270

9.5 mm diameter at 160

No stirrups

ACI 83, ACI 89,*

CSA 84

Min Ay, s = d/2

0.60 CSA 94 min A„ s < d/2

1.00 ACI 89t min A* s < d/2

•Lower amount of minimum *4 provided when *jf ií a/69 MPa in design.

V

tUpper amount of minimum A provided when Jf/

v

c

> a/69 MPa in design.

2

Noterj^. for all stirrups is 430 MPa; area of 8.0-mm-diamcter bar = 50 mm ; area of

2

9.5-mm-diameter bar = 7! mm .

The purpose of the paper was to evaluate the minimum shear reinforcement

requirements in normal, medium, and high-strength reinforced concrete beams. Therefore

the tested beams were reinforced with minimum shear reinforcement, except three

50

specimens without shear reinforcement ( N l - S , M l - S and H l - S ) . Here these test data are

used for evaluation of shear design methods under the effects of concrete strength, stirrup

spacing and shear reinforcement,

Table 5-2 gives the test results and a comparison of predicted and measured shear

capacities of specimens. The predictions using the shear friction method and the

simplified method agree well with the experimental results with value of C.O.V. 6.8%

and 12.5% respectively, while the prediction using the general method results in a higher

value of C.O.V. 23.7%.

Table. 5-2, Test Results and Comparison of Predictions

V,

Vf

Vsim

Vg

Specimen

(kN)

(kN)

(kN)

(kN)

Vt/V,,

v /v

Nl-S

249

208

232

204

1.199

Nl-N

N2-S

N2-N

Ml-S

Ml-N

M2-S

M2-N

Hl-S

Hl-N

H2-S

H2-N

457

363

483

296

405

552

689

376

354

436

270

411

468

567

302

432

534

712

318

318

418

316

403

525

576

360

209

208

404

278

269

455

504

1.216

1.025

1.108

1.096

0.985

1.180

1.214

1.075

1.436

316

1.082

447

606

708

300

526

625

1.117

1.119

1.012

m

a

327

483

598

721

S

C.O.V.

t

sim

1.143

1.156

0.937

1.006

1.051

1.196

0.908

1.082

0.986

Vt/V

g

1.223

2.188

1.741

1.194

1.066

1.508

1.213

1.367

1.034

1.018

1.612

1.136

1.154

1.11

1.08

1.37

0.075

6.8%

0.135

12.5%

0.325

23.7%

51

The analyses of the 9 beams with shear reinforcement are illustrated from Fig. 5-2

to 5-10. In Fig. 5-2, the ratios of test results to the results predicted by the shear friction

method against concrete strength, f' , are plotted to demonstrate the effect of concrete

c

strength on the shear friction method. It shows no obvious trend in the prediction of shear

capacity for beams with different concrete strength. Fig. 5-3 and Fig 5-4 present the

analysis results of the effects of concrete strength using the C S A simplified method and

general method respectively. A downward trend exists for both of methods.

2.5

2

V

t

Vrf

•••

1.5

•

•

•

1

•

•

-tr

0.5

30

40

50

60

70

80

f c (MPa)

Fig. 5-2, Effect of Concrete Strength on the Shear Friction Method

90

2.5r

1.5-

•

Vsim

•••

1

•

V

t

•

-B-

0.5

0

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

f c (MPa)

Fig. 5-3, Effect of Concrete Strength on the Simplified Method

2.5r

V

t

•••

-s•

•

1-5

1

0.5

0

30

40

50

60

f

c

70

80

(MPa)

Fig. 5-4, Effect of Concrete Strength on the General Method

90

53

The ratios of test results to the results predicted by the shear friction method

against the ratios of s/d and the web reinforcement index Pyfyy are plotted in Fig. 5-5 and

Fig. 5-6 respectively. The shear friction method demonstrates a consistent accuracy of the

prediction of shear capacity for beams with different stirrup spacing and different

amounts of shear reinforcement.

In Fig. 5-7 to Fig. 5-10, the measured/calculated ratios of shear capacity versus

the ratios of s/d and the web reinforcement index / V v y by

m

e

C S A simplified method

and general method are plotted. There is a larger scatter for these results than the scatter

when shear strength is predicted by shear friction. Notice that the scatter gets

significantly larger around / V v y

=

0.3 ~ 0.4. The reason is that some specimens are just

under the minimum shear reinforcement requirement by the code and the application of

different equations creates inconsistent conservative results. Fig.5-9 also shows that when

the ratio of s/d increases the general method tends to be more conservative.

2.5

2

•

Vrf

• ••

o

1

•

•

o

0.4

0.5

•

0.5

0

0.2

0.3

0.6

s

d

Fig. 5-5, Effect of Stirrup Spacing on the Shear Friction Method

0.7

1

2.5r

V

t

:

I

r

r

i

r

i

15

•

•

•

Vsf

• •D

I

•

1

0.5

0

0.2

J

I

I

I

I

I

I

L

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1

1.1

f

p - vy(MPa)

v

Fig. 5-6, Effect of Shear Reinforcement on the Shear Friction Method

2.51

V

t

15