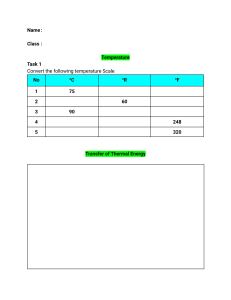

Numerical Analysis of the Thermal Performance of a Contemporary CEB Tiny House Andreas Kyriakidis∗†1 , Marios Kyriakides‡2,3 , Rafail Panagiotou∗§2 , David Castrillo4 , Maria Costi De Castrillo¶4 , Rogiros Illampas∗5 , Aimilios Michael‖1 , and Ioannis Ioannou∗∗2 1 Department of Architecture, University of Cyprus – Cyprus Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Cyprus – Cyprus 3 Department of Engineering, University of Nicosia – Cyprus 4 Between the Lines Ltd, Nicosia – Cyprus 5 Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Cyprus – Cyprus 2 Abstract Compressed earth blocks (CEBs) are the modern evolution of adobe bricks, an earth building technique dating to prehistoric times [1]. Although industrialization has led to a decline in the use of earthen building materials, including CEBs, since the 1950s, the latter are lately re-gaining attention due to their sustainable nature and low production cost. However, in order for CEBs to be used in contemporary construction, a holistic approach must be adopted that analyzes all parameters involved in material production and use. In this paper, the thermal performance of a CEB masonry system and of a contemporary CEB ‘tiny house’ (Figure 1a) are evaluated. A ‘tiny house’ is an aesthetically attractive, environmentally friendly structure, with an area ≤ 35 m2. Its prototype architectural design was derived based on the physico-mechanical properties of non-stabilized CEBs produced in Cyprus with local raw materials [2]. The research work presented includes the computation of the time lag and decrement factor of the proposed masonry system. The results obtained are compared against corresponding properties of other typical construction systems. Subsequently, the thermal performance of the CEB house is numerically examined. All thermo-physical properties used in the analyses were adopted from EN ISO 10456:2007 [3], except from those of the CEBs that were acquired through laboratory tests (Figure 1b). The proposed masonry system comprises of 0.30 m thick CEBs with thermal conductivity 1.032 W/mK, density 2070 kg/m3 and specific heat capacity 724 J/kgK. The interior and exterior surfaces of the walls are covered with 0.05 m thick extruded polystyrene and are coated with 0.025 m thick lime plaster. The use of polystyrene was deemed necessary (despite the fact that this material is not sustainable and masks the hydrothermal advantages of CEBs) in order to satisfy local thermal regulations, which impose U-values ≤ 0.4 W/m2K ∗ Speaker Corresponding author: kyriakidis.andreas@ucy.ac.cy ‡ Corresponding author: kyriakides.marios@ucy.ac.cy § Corresponding author: panagiotou.rafail@ucy.ac.cy ¶ Corresponding author: mariacosticastrillo@gmail.com ‖ Corresponding author: aimilios@ucy.ac.cy ∗∗ Corresponding author: ioannis@ucy.ac.cy † sciencesconf.org:conf-earth:379923 for new constructions, irrespective of the building material used [4]. The performance of the CEB masonry system was compared against walls constructed of perforated fired clay bricks with external insulation, and drywall panel infills. Time lag and decrement factor were computed through time-dependent transient heat transfer analysis [5] in Comsol Multiphysics 5.2. For the thermal analysis of the ‘tiny house’, and the assessment of heating and cooling loads, Energy Plus through OpenStudio was used. The proposed structure was modelled as a single thermal zone, to assess the entire building’s heating and cooling loads (Figure 1c). Shading surfaces were used to model the external shading, the roof protrusions, and the thickness of the external masonry. For the roof, an insulated reinforced concrete slab was assumed. For the ground, a reinforced concrete slab covered with ceramic tiles was considered. For the openings, windows with thermal transmittance equal to 2.25 W/m2K were adopted. The city of Larnaca in Cyprus was selected as representative of the island’s climate characteristics, while weather data from the Energy Plus database were used (https://energyplus.net). To account for the possible effects of building use on the overall thermal performance of the building envelope, internal heat gains and occupancy were considered. Typical values of lighting, appliances and activity level of people for a residential building were used. Indoor desired conditions and time schedule profiles were selected in accordance with EN 167981:2019 [6]. The results obtained for the proposed masonry system and other typical wall constructions indicate that the CEB masonry system exhibits similar, or even better, thermal performance, mostly due to its high thermal mass. The thermal analysis of the ‘tiny house’ shows that the heating loads are significantly lower than the cooling loads. This was pretty much expected and it is attributed to the local climatic conditions, the building’s geometry, size, envelope and use [7, 8]. More specifically, Larnaca is generally characterized by hot summers, with intense solar irradiation, and mild winters. The rectangular shape of the building with a north-south orientation, and the big openings on the east, south and west walls, maximize solar exploitation, thus minimizing heating needs during winter. At the same time, they increase cooling needs during the summer period [7-12]. The use of external insulation minimizes heat losses and gains through the building’s envelope, while the high thermal inertia of the building’s walls contributes to the reduction of the internal temperature fluctuation, thus establishing more stable indoor thermal conditions [12-14]. Finally, the internal loads from people, the lighting and electric equipment, contribute to the reduction of heating loads, but also increase cooling loads during the summer period [8]. With regards to heat gains and losses, most occur through the roof, despite the fact that the latter is insulated. Significant heat gains also occur through the external windows, mostly due to their size and orientation [9, 10]. As expected, heat gains from people, electric equipment and infiltration constitute a significant portion of the overall heat gains of the building, mostly due to its small size. Regarding the external walls, the higher solar irradiation occurred on the south wall; this resulted in higher heat gains, while higher heat losses occurred on both the south and north walls, mostly due to their size [10, 11]. The authors would like to acknowledge financial support by the European Regional Development Fund and the Republic of Cyprus, through the Cyprus Research and Innovation Foundation (Project ENTERPRISES/0618/0007). II and RP would also like to acknowledge funding by the University of Cyprus. They would also like to thank Mr. M. Tapakoudis from Gigantas Antaios Touvlopiio Ltd for helping with the production of CEBs.