Strength and Conditioning: Biological Principles & Applications

advertisement

Strength and Conditioning

Biological Principles and Practical Applications

Edited by

Marco Cardinale, Rob Newton and Kazunori Nosaka

A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication

ffirs.indd iii

10/18/2010 5:12:11 PM

flast.indd xx

10/18/2010 5:12:12 PM

Strength and Conditioning

ffirs.indd i

10/18/2010 5:12:11 PM

ffirs.indd ii

10/18/2010 5:12:11 PM

Strength and Conditioning

Biological Principles and Practical Applications

Edited by

Marco Cardinale, Rob Newton and Kazunori Nosaka

A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication

ffirs.indd iii

10/18/2010 5:12:11 PM

This edition first published 2011 © 2011, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Wiley-Blackwell is an imprint of John Wiley & Sons, formed by the merger of Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical

and Medical business with Blackwell Publishing.

Registered office: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

Editorial Offices: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK

The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK

111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for

permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/

wiley-blackwell

The right of the author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted

by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names

and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their

respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book. This

publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered.

It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services. If professional

advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Strength and conditioning – biological principles and practical applications / edited by Marco Cardinale, Rob

Newton, and Kazunori Nosaka.

p. ; cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-01918-4 (cloth) – ISBN 978-0-470-01919-1 (pbk.)

1. Muscle strength. 2. Exercise–Physiological aspects. 3. Physical education and training. I. Cardinale,

Marco. II. Newton, Rob (Robert U.) III. Nosaka, Kazunori.

[DNLM: 1. Physical Fitness. 2. Exercise. 3. Physical Endurance. QT 255]

QP321.S885 2011

613.7′11–dc22

2010029179

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book is published in the following electronic format: ePDF 9780470970003

Set in 9 on 10.5pt Times by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

First Impression 2011

ffirs.indd iv

10/21/2010 3:17:13 PM

Contents

Foreword by Sir Clive Woodward

Preface

List of Contributors

1.2.3.3 Surface EMG for noninvasive

neuromuscular assessment

xiii

xv

xvii

1.3

Section 1 Strength and Conditioning

Biology

1.1 Skeletal Muscle Physiology

Valmor Tricoli

1.1.1 Introduction

1.1.2 Skeletal Muscle Macrostructure

1.1.3 Skeletal Muscle Microstructure

1.1.3.1 Sarcomere and myofilaments

1.1.3.2 Sarcoplasmic reticulum and

transverse tubules

1.1.4 Contraction Mechanism

1.1.4.1 Excitation–contraction (E-C)

coupling

1.1.4.2 Skeletal muscle contraction

1.1.5 Muscle Fibre Types

1.1.6 Muscle Architecture

1.1.7 Hypertrophy and Hyperplasia

1.1.8 Satellite Cells

1.2

ftoc.indd v

1

3

3

3

3

4

7

7

7

7

9

10

11

12

Neuromuscular Physiology

Alberto Rainoldi and Marco Gazzoni

17

1.2.1 The Neuromuscular System

1.2.1.1 Motor units

1.2.1.2 Muscle receptors

1.2.1.3 Nervous and muscular conduction

velocity

1.2.1.4 Mechanical output production

1.2.1.5 Muscle force modulation

1.2.1.6 Electrically elicited contractions

1.2.2 Muscle Fatigue

1.2.2.1 Central and peripheral fatigue

1.2.2.2 The role of oxygen availability

in fatigue development

1.2.3 Muscle Function Assessment

1.2.3.1 Imaging techniques

1.2.3.2 Surface EMG as a muscle imaging

tool

17

17

17

18

18

20

22

22

22

23

23

23

24

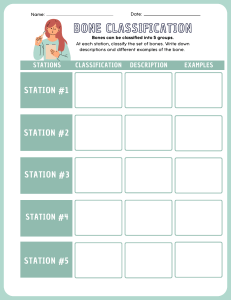

Bone Physiology

Jörn Rittweger

1.3.1 Introduction

1.3.2 Bone Anatomy

1.3.2.1 Bones as organs

1.3.2.2 Bone tissue

1.3.2.3 The material level: organic

and inorganic constituents

1.3.3 Bone Biology

1.3.3.1 Osteoclasts

1.3.3.2 Osteoblasts

1.3.3.3 Osteocytes

1.3.4 Mechanical Functions of Bone

1.3.4.1 Material properties

1.3.4.2 Structural properties

1.3.5 Adaptive Processes in Bone

1.3.5.1 Modelling

1.3.5.2 Remodelling

1.3.5.3 Theories of bone adaptation

1.3.5.4 Mechanotransduction

1.3.6 Endocrine Involvement of Bone

1.3.6.1 Calcium homoeostasis

1.3.6.2 Phosphorus homoeostasis

1.3.6.3 Oestrogens

1.4

25

29

29

29

29

30

31

32

32

32

33

33

33

34

35

35

35

36

37

38

38

38

38

Tendon Physiology

45

Nicola Maffulli, Umile Giuseppe Longo,

Filippo Spiezia and Vincenzo Denaro

1.4.1

1.4.2

1.4.3

1.4.4

1.4.5

1.4.6

1.4.7

1.4.8

1.4.9

1.4.10

Tendons

The Musculotendinous Junction

The Oseotendinous Junction

Nerve Supply

Blood Supply

Composition

Collagen Formation

Cross-Links

Elastin

Cells

45

46

46

46

46

47

47

47

48

48

10/19/2010 10:00:56 AM

vi

CONTENTS

1.4.11

1.4.12

Ground Substance

Crimp

1.5 Bioenergetics of Exercise

Ron J. Maughan

1.5.1 Introduction

1.5.2 Exercise, Energy, Work, and Power

1.5.3 Sources of Energy

1.5.3.1 Phosphagen metabolism

1.5.3.2 The glycolytic system

1.5.3.3 Aerobic metabolism: oxidation

of carbohydrate, lipid, and protein

1.5.4 The Tricarboxylic Acid (TCA) Cycle

1.5.5 Oxygen Delivery

1.5.6 Energy Stores

1.5.7 Conclusion

1.6 Respiratory and Cardiovascular

Physiology

Jeremiah J. Peiffer and Chris R. Abbiss

1.6.1 The Respiratory System

1.6.1.1 Introduction

1.6.1.2 Anatomy

1.6.1.3 Gas exchange

1.6.1.4 Mechanics of ventilation

1.6.1.5 Minute ventilation

1.6.1.6 Control of ventilation

1.6.2 The Cardiovascular System

1.6.2.1 Introduction

1.6.2.2 Anatomy

1.6.2.3 The heart

1.6.2.4 The vascular system

1.6.2.5 Blood and haemodynamics

1.6.3 Conclusion

1.7

1.7.2.6 Signalling associated with muscle

protein breakdown

1.7.2.7 Satellite-cell regulation during

strength training

1.7.2.8 What we have not covered

53

53

53

54

55

56

57

57

58

58

60

63

63

63

63

63

66

67

68

68

68

68

70

71

72

74

Genetic and Signal Transduction

Aspects of Strength Training

77

Henning Wackerhage, Arimantas Lionikas,

Stuart Gray and Aivaras Ratkevicius

1.7.1 Genetics of Strength and Trainability

1.7.1.1 Introduction to sport and exercise

genetics

1.7.1.2 Heritability of muscle mass,

strength, and strength trainability

1.7.2 Signal Transduction Pathways that

Mediate the Adaptation to Strength

Training

1.7.2.1 Introduction to adaptation to

exercise: signal transduction

pathway regulation

1.7.2.2 Human protein synthesis and

breakdown after exercise

1.7.2.3 The AMPK–mTOR system and the

regulation of protein synthesis

1.7.2.4 Potential practical implications

1.7.2.5 Myostatin–Smad signalling

ftoc.indd vi

48

48

77

77

77

79

79

80

81

82

83

1.8

Strength and Conditioning

Biomechanics

Robert U. Newton

83

84

84

89

1.8.1 Introduction

89

1.8.1.1 Biomechanics and sport

89

1.8.2 Biomechanical Concepts for Strength

and Conditioning

89

1.8.2.1 Time, distance, velocity, and

acceleration

90

1.8.2.2 Mass, force, gravity, momentum,

work, and power

90

1.8.2.3 Friction

91

1.8.3 The Force–Velocity–Power Relationship 91

1.8.4 Musculoskeletal Machines

92

1.8.4.1 Lever systems

92

1.8.4.2 Wheel-axle systems

93

1.8.5 Biomechanics of Muscle Function

93

1.8.5.1 Length–tension effect

93

1.8.5.2 Muscle angle of pull

93

1.8.5.3 Strength curve

94

1.8.5.4 Line and magnitude of resistance

95

1.8.5.5 Sticking region

95

1.8.5.6 Muscle architecture, strength,

and power

95

1.8.5.7 Multiarticulate muscles, active

and passive insufficiency

96

1.8.6 Body Size, Shape, and Power-ToWeight Ratio

96

1.8.7 Balance and Stability

96

1.8.7.1 Factors contributing to stability

96

1.8.7.2 Initiating movement or change

of motion

97

1.8.8 The Stretch–Shortening Cycle

97

1.8.9 Biomechanics of Resistance

Machines

98

1.8.9.1 Free weights

98

1.8.9.2 Gravity-based machines

98

1.8.9.3 Hydraulic resistance

99

1.8.9.4 Pneumatic resistance

99

1.8.9.5 Elastic resistance

100

1.8.10 Machines vs Free Weights

100

1.8.11 Conclusion

100

Section 2 Physiological adaptations to

strength and conditioning

2.1 Neural Adaptations to Resistance

Exercise

Per Aagaard

2.1.1 Introduction

2.1.2 Effects of Strength Training on

Mechanical Muscle Function

103

105

105

105

10/19/2010 10:00:56 AM

CONTENTS

2.1.2.1 Maximal concentric and eccentric

muscle strength

2.1.2.2 Muscle power

2.1.2.3 Contractile rate of force

development

2.1.3 Effects of Strength Training on

Neural Function

2.1.3.1 Maximal EMG amplitude

2.1.3.2 Contractile RFD: changes in

neural factors with strength

training

2.1.3.3 Maximal eccentric muscle

contraction: changes in neural

factors with strength training

2.1.3.4 Evoked spinal motor neuron

responses

2.1.3.5 Excitability in descending

corticospinal pathways

2.1.3.6 Antagonist muscle coactivation

2.1.3.7 Force steadiness, fine motor

control

2.1.4 Conclusion

2.2 Structural and Molecular Adaptations

to Training

Jesper L. Andersen

2.2.1 Introduction

2.2.2 Protein Synthesis and Degradation

in Human Skeletal Muscle

2.2.3 Muscle Hypertrophy and Atrophy

2.2.3.1 Changes in fibre type composition

with strength training

2.2.4 What is the Significance of Satellite

Cells in Human Skeletal Muscle?

2.2.5 Concurrent Strength and Endurance

Training: Consequences for Muscle

Adaptations

2.3 Adaptive Processes in Human Bone

and Tendon

Constantinos N. Maganaris, Jörn

Rittweger and Marco V. Narici

2.3.1 Introduction

2.3.2 Bone

2.3.2.1 Origin of musculoskeletal forces

2.3.2.2 Effects of immobilization on

bone

2.3.2.3 Effects of exercise on bone

2.3.2.4 Bone adaptation across the

life span

2.3.3 Tendon

2.3.3.1 Functional and mechanical

properties

2.3.3.2 In vivo testing

2.3.3.3 Tendon adaptations to altered

mechanical loading

2.3.4 Conclusion

ftoc.indd vii

105

106

107

107

108

109

110

114

116

116

119

119

125

2.4 Biochemical Markers and Resistance

Training

Christian Cook and Blair Crewther

vii

155

2.4.1 Introduction

2.4.2 Testosterone Responses to Resistance

Training

2.4.2.1 Effects of workout design

2.4.2.2 Effects of age and gender

2.4.2.3 Effects of training history

2.4.3 Cortisol Responses to Resistance

Training

2.4.3.1 Effects of workout design

2.4.3.2 Effects of age and gender

2.4.3.3 Effects of training history

2.4.4 Dual Actions of Testosterone and

Cortisol

2.4.5 Growth Hormone Responses to

Resistance Training

2.4.5.1 Effects of workout design

2.4.5.2 Effects of age and gender

2.4.5.3 Effects of training history

2.4.6 Other Biochemical Markers

2.4.7 Limitations in the Use and

Interpretation of Biochemical Markers

2.4.8 Applications of Resistance Training

2.4.9 Conclusion

155

155

155

156

156

156

156

157

157

157

157

158

158

158

158

159

159

160

125

2.5

125

127

128

131

132

137

137

137

137

138

140

140

141

141

143

143

147

Cardiovascular Adaptations to

Strength and Conditioning

165

Andrew M. Jones and Fred J. DiMenna

2.5.1 Introduction

2.5.2 Cardiovascular Function

2.5.2.1 Oxygen uptake

2.5.2.2 Maximal oxygen uptake

2.5.2.3 Cardiac output

2.5.2.4 Cardiovascular overload

2.5.2.5 The cardiovascular training

stimulus

2.5.2.6 Endurance exercise training

2.5.3 Cardiovascular Adaptations to Training

2.5.3.1 Myocardial adaptations to

endurance training

2.5.3.2 Circulatory adaptations to

endurance training

2.5.4 Cardiovascular-Related Adaptations

to Training

2.5.4.1 The pulmonary system

2.5.4.2 The skeletal muscular system

2.5.5 Conclusion

2.6 Exercise-induced Muscle Damage

and Delayed-onset Muscle Soreness

(DOMS)

Kazunori Nosaka

2.6.1 Introduction

2.6.2 Symptoms and Markers of

Muscle Damage

165

165

165

165

165

166

167

167

167

167

170

172

172

173

174

179

179

179

10/19/2010 10:00:56 AM

viii

CONTENTS

2.6.2.1 Symptoms

2.6.2.2 Histology

2.6.2.3 MRI and B-mode ultrasound

images

2.6.2.4 Blood markers

2.6.2.5 Muscle function

2.6.2.6 Exercise economy

2.6.2.7 Range of motion (ROM)

2.6.2.8 Swelling

2.6.2.9 Muscle pain

2.6.3 Relationship between Doms and

Other Indicators

2.6.4 Factors Influencing the Magnitude

of Muscle Damage

2.6.4.1 Contraction parameters

2.6.4.2 Training status

2.6.4.3 Repeated-bout effect

2.6.4.4 Muscle

2.6.4.5 Other factors

2.6.5 Muscle Damage and Training

2.6.5.1 The importance of eccentric

contractions

2.6.5.2 The possible role of muscle

damage in muscle hypertrophy

and strength gain

2.6.5.3 No pain, no gain?

2.6.6 Conclusion

2.7 Alternative Modalities of Strength

and Conditioning: Electrical

Stimulation and Vibration

Nicola A. Maffiuletti and Marco

Cardinale

2.7.1 Introduction

2.7.2 Electrical-Stimulation Exercise

2.7.2.1 Methodological aspects: ES

parameters and settings

2.7.2.2 Physiological aspects: motor unit

recruitment and muscle fatigue

2.7.2.3 Does ES training improve muscle

strength?

2.7.2.4 Could ES training improve sport

performance?

2.7.2.5 Practical suggestions for ES use

2.7.3 Vibration Exercise

2.7.3.1 Is vibration a natural stimulus?

2.7.3.2 Vibration training is not just

about vibrating platforms

2.7.3.3 Acute effects of vibration in

athletes

2.7.3.4 Acute effects of vibration

exercise in non-athletes

2.7.3.5 Chronic programmes of vibration

training in athletes

2.7.3.6 Chronic programmes of vibration

training in non-athletes

ftoc.indd viii

179

179

2.7.3.7 Applications in rehabilitation

2.7.3.8 Safety considerations

203

203

180

180

181

182

182

182

183

2.8 The Stretch–Shortening Cycle (SSC)

Anthony Blazevich

209

2.8.1 Introduction

2.8.2 Mechanisms Responsible for

Performance Enhancement with

the SSC

2.8.2.1 Elastic mechanisms

2.8.2.2 Contractile mechanisms

2.8.2.3 Summary of mechanisms

2.8.3 Force Unloading: A Requirement

for Elastic Recoil

2.8.4 Optimum MTU Properties for SSC

Performance

2.8.5 Effects of the Transition Time

between Stretch and Shortening

on SSC Performance

2.8.6 Conclusion

209

184

184

185

185

185

186

186

187

187

187

188

188

193

193

193

193

194

195

196

196

197

200

201

201

202

202

203

209

209

212

216

216

217

218

218

2.9 Repeated-sprint Ability (RSA)

David Bishop and Olivier Girard

223

2.9.1 Introduction

2.9.1.1 Definitions

2.9.1.2 Indices of RSA

2.9.2 Limiting Factors

2.9.2.1 Muscular factors

2.9.2.2 Neuromechanical factors

2.9.2.3 Summary

2.9.3 Ergogenic aids and RSA

2.9.3.1 Creatine

2.9.3.2 Carbohydrates

2.9.3.3 Alkalizing agents

2.9.3.4 Caffeine

2.9.3.5 Summary

2.9.4 Effects of Training on RSA

2.9.4.1 Introduction

2.9.4.2 Training the limiting factors

2.9.4.3 Putting it all together

2.9.5 Conclusion

223

223

223

223

224

227

229

229

230

230

230

231

232

232

232

232

235

235

2.10 The Overtraining Syndrome (OTS)

Romain Meeusen and Kevin De Pauw

243

2.10.1 Introduction

2.10.2 Definitions

2.10.2.1 Functional overreaching (FO)

2.10.2.2 Nonfunctional overreaching

(NFO)

2.10.2.3 The overtraining syndrome

(OTS)

2.10.2.4 Summary

2.10.3 Prevalence

2.10.4 Mechanisms and Diagnosis

2.10.4.1 Hypothetical mechanisms

2.10.4.2 Biochemistry

243

243

243

244

244

244

244

245

245

245

10/19/2010 10:00:56 AM

CONTENTS

2.10.4.3 Physiology

2.10.4.4 The immune system

2.10.4.5 Hormones

2.10.4.6 Is the brain involved?

2.10.4.7 Training status

2.10.4.8 Psychometric measures

2.10.4.9 Psychomotor speed

2.10.4.10 Are there definitive

diagnostic criteria?

2.10.5 Prevention

2.10.6 Conclusion

Section 3 Monitoring strength and

conditioning progress

3.1 Principles of Athlete Testing

Robert U. Newton, Prue Cormie and

Marco Cardinale

3.1.1 Introduction

3.1.2 General Principles of Testing

Athletes

3.1.2.1 Validity

3.1.2.2 Reliability

3.1.2.3 Specificity

3.1.2.4 Scheduling

3.1.2.5 Selection of movement tested

3.1.2.6 Stretching and other preparation

for the test

3.1.3 Maximum Strength

3.1.3.1 Isoinertial strength testing

3.1.3.2 Isometric strength testing

3.1.3.3 Isokinetic strength testing

3.1.4 Ballistic Testing

3.1.4.1 Jump squats

3.1.4.2 Rate of force development

(RFD)

3.1.4.3 Temporal phase analysis

3.1.4.4 Equipment and analysis methods

for ballistic testing

3.1.5 Reactive Strength Tests

3.1.6 Eccentric Strength Tests

3.1.6.1 Specific tests of skill

performance

3.1.6.2 Relative or absolute measures

3.1.7 Conclusion

245

246

246

246

247

247

247

248

248

249

253

255

3.3.1 Introduction

3.3.1.1 Energy systems

3.3.1.2 The importance of anaerobic

capacity and RSA

3.3.2 Testing Anaerobic Capacity

3.3.2.1 Definition

3.3.2.2 Assessment

3.3.3 Testing Repeated-Sprint Ability

3.3.3.1 Definition

3.3.3.2 Assessment

3.3.4 Conclusion

3.4

255

255

255

255

255

256

256

256

257

257

258

259

259

260

261

261

264

265

266

267

267

267

3.2 Speed and Agility Assessment

Warren Young and Jeremy Sheppard

271

3.2.1 Speed

3.2.1.1 Introduction

3.2.1.2 Testing acceleration speed

3.2.1.3 Testing maximum speed

3.2.1.4 Testing speed endurance

3.2.1.5 Standardizing speed-testing

protocols

3.2.2 Agility

3.2.3 Conclusion

271

271

271

272

272

ftoc.indd ix

3.3 Testing Anaerobic Capacity and

Repeated-sprint Ability

David Bishop and Matt Spencer

273

273

275

ix

277

277

277

277

277

277

279

284

284

284

286

Cardiovascular Assessment and

Aerobic Training Prescription

291

Andrew M. Jones and Fred J. DiMenna

3.4.1 Introduction

3.4.2 Cardiovascular Assessment

3.4.2.1 Health screening and risk

stratification

3.4.2.2 Cardiorespiratory fitness

and VO2max

3.4.2.3 Submaximal exercise testing

3.4.2.4 Maximal exercise testing

3.4.3 Aerobic Training Prescription

3.4.3.1 Specificity and aerobic overload

3.4.3.2 Mode

3.4.3.3 Frequency

3.4.3.4 Total volume

3.4.3.5 Intensity

3.4.3.6 Total volume vs volume per

unit time

3.4.3.7 Progression

3.4.3.8 Reversibility

3.4.3.9 Parameter-specific

cardiorespiratory enhancement

3.4.3.10 VO2max improvement

3.4.3.11 Exercise economy improvement

3.4.3.12 LT/LTP improvement

3.4.3.13 VO2 kinetics improvement

3.4.3.14 Prescribing exercise for

competitive athletes

3.4.4 Conclusion

3.5 Biochemical Monitoring in Strength

and Conditioning

Michael R. McGuigan and Stuart J.

Cormack

3.5.1 Introduction

3.5.2 Hormonal Monitoring

3.5.2.1 Cortisol

3.5.2.2 Testosterone

3.5.2.3 Catecholamines

3.5.2.4 Growth hormone

291

291

291

291

292

292

297

297

297

297

298

298

298

299

299

299

299

300

300

300

301

301

305

305

305

305

305

306

306

10/19/2010 10:00:56 AM

x

CONTENTS

3.5.2.5 IGF

306

3.5.2.6 Leptin

307

3.5.2.7 Research on hormones in sporting

environments

307

3.5.2.8 Methodological considerations

308

3.5.3 Metabolic Monitoring

308

3.5.3.1 Muscle biopsy

308

3.5.3.2 Biochemical testing

309

3.5.4 Immunological and Haematological

Monitoring

309

3.5.4.1 Immunological markers

309

3.5.4.2 Haematological markers

310

3.5.5 Practical Application

310

3.5.5.1 Evaluating the effects of training 310

3.5.5.2 Assessment of training workload 311

3.5.5.3 Monitoring of fatigue

311

3.5.5.4 Conclusions and specific advice for

implementation of a biochemical

monitoring programme

311

3.6 Body Composition: Laboratory and

Field Methods of Assessment

Arthur Stewart and Tim Ackland

3.6.1 Introduction

3.6.2 History of Body Composition

Methods

3.6.3 Fractionation Models for Body

Composition

3.6.4 Biomechanical Imperatives for Sports

Performance

3.6.5 Methods of Assessment

3.6.5.1 Laboratory methods

3.6.5.2 Field methods

3.6.6 Profiling

3.6.7 Conclusion

317

317

317

317

318

319

319

323

330

330

3.7 Total Athlete Management (TAM)

and Performance Diagnosis

335

Robert U. Newton and Marco Cardinale

3.7.1 Total Athlete Management

335

3.7.1.1 Strength and conditioning

335

3.7.1.2 Nutrition

335

3.7.1.3 Rest and recovery

336

3.7.1.4 Travel

336

3.7.2 Performance Diagnosis

336

3.7.2.1 Optimizing training-programme

design and the window of

adaptation

337

3.7.2.2 Determination of key performance

characteristics

338

3.7.2.3 Testing for specific performance

qualities

339

3.7.2.4 What to look for

339

3.7.2.5 Assessing imbalances

339

3.7.2.6 Session rating of

perceived exertion

340

ftoc.indd x

3.7.2.7 Presenting the results

3.7.2.8 Sophisticated is not necessarily

expensive

3.7.2.9 Recent advances and the future

3.7.3 Conclusion

340

340

341

342

Section 4 Practical applications

4.1 Resistance Training Modes:

A Practical Perspective

Michael H. Stone and Margaret

E. Stone

345

347

4.1.1 Introduction

4.1.2 Basic Training Principles

4.1.2.1 Overload

4.1.2.2 Variation

4.1.2.3 Specificity

4.1.3 Strength, Explosive Strength,

and Power

4.1.3.1 Joint-angle specificity

4.1.3.2 Movement-pattern specificity

4.1.3.3 Machines vs free weights

4.1.3.4 Practical considerations:

advantages and disadvantages

associated with different

modes of training

4.1.4 Conclusion

347

348

348

348

348

348

349

350

351

355

357

4.2 Training Agility and Change-ofdirection Speed (CODS)

Jeremy Sheppard and Warren Young

4.2.1 Factors Affecting Agility

4.2.2 Organization of Training

4.2.3 Change-of-Direction Speed

4.2.3.1 Leg-strength qualities and CODS

4.2.3.2 Technique

4.2.3.3 Anthropometrics and CODS

4.2.4 Perceptual and Decision-Making

Factors

4.2.5 Training Agility

4.2.6 Conclusion

4.3 Nutrition for Strength Training

Christopher S. Shaw and

Kevin D. Tipton

4.3.1 Introduction

4.3.2 The Metabolic Basis of Muscle

Hypertrophy

4.3.3 Optimal Protein Intake

4.3.3.1 The importance of energy

balance

4.3.4 Acute Effects of Amino Acid/Protein

Ingestion

4.3.4.1 Amino acid source

4.3.4.2 Timing

4.3.4.3 Dose

4.3.4.4 Co-ingestion of other nutrients

363

363

363

364

366

366

369

370

371

374

377

377

377

377

378

379

379

381

382

382

10/19/2010 10:00:57 AM

CONTENTS

4.3.4.5 Protein supplements

4.3.4.6 Other supplements

4.3.5 Conclusion

4.4

Flexibility

William A. Sands

4.4.1 Definitions

4.4.2 What is Stretching?

4.4.3 A Model of Effective Movement: The

Integration of Flexibility and Strength

4.5

5.1.3.5 Training of sport-specific

movements

5.1.4 Conclusion

389

5.2 Strength Training for Children

and Adolescents

Avery D. Faigenbaum

389

390

393

Sensorimotor Training

399

Urs Granacher, Thomas Muehlbauer,

Wolfgang Taube, Albert Gollhofer and

Markus Gruber

4.5.1 Introduction

4.5.2 The Importance of Sensorimotor

Training to the Promotion of Postural

Control and Strength

4.5.3 The Effects of Sensorimotor Training

on Postural Control and Strength

4.5.3.1 Sensorimotor training in healthy

children and adolescents

4.5.3.2 Sensorimotor training in healthy

adults

4.5.3.3 Sensorimotor training in healthy

seniors

4.5.4 Adaptive Processes Following

Sensorimotor Training

4.5.5 Characteristics of Sensorimotor

Training

4.5.5.1 Activities

4.5.5.2 Load dimensions

4.5.5.3 Supervision

4.5.5.4 Efficiency

4.5.6 Conclusion

Section 5 Strength and Conditioning

special cases

5.1 Strength and Conditioning as a

Rehabilitation Tool

Andreas Schlumberger

5.1.1 Introduction

5.1.2 Neuromuscular Effects of Injury as

a Basis for Rehabilitation Strategies

5.1.3 Strength and Conditioning in

Retraining of the Neuromuscular

System

5.1.3.1 Targeted muscle overloading:

criteria for exercise choice

5.1.3.2 Active lengthening/eccentric

training

5.1.3.3 Passive lengthening/stretching

5.1.3.4 Training of the muscles of the

lumbopelvic hip complex

ftoc.indd xi

383

383

383

399

400

401

401

401

401

402

402

402

403

405

405

406

411

413

413

414

415

415

417

419

421

5.2.1 Introduction

5.2.2 Risks and Concerns Associated with

Youth Strength Training

5.2.3 The Effectiveness of Youth

Resistance Training

5.2.3.1 Persistence of training-induced

strength gains

5.2.3.2 Programme evaluation

and testing

5.2.4 Physiological Mechanisms for

Strength Development

5.2.5 Potential Health and Fitness Benefits

5.2.5.1 Cardiovascular risk profile

5.2.5.2 Bone health

5.2.5.3 Motor performance skills and

sports performance

5.2.5.4 Sports-related injuries

5.2.6 Youth Strength-Training Guidelines

5.2.6.1 Choice and order of exercise

5.2.6.2 Training intensity and volume

5.2.6.3 Rest intervals between sets

and exercises

5.2.6.4 Repetition velocity

5.2.6.5 Training frequency

5.2.6.6 Programme variation

5.2.7 Conclusion

Acknowledgements

5.3

Strength and Conditioning

Considerations for the Paralympic

Athlete

Mark Jarvis, Matthew Cook and

Paul Davies

5.3.1 Introduction

5.3.2 Programming Considerations

5.3.3 Current Controversies in Paralympic

Strength and Conditioning

5.3.4 Specialist Equipment

5.3.5 Considerations for Specific

Disability Groups

5.3.5.1 Spinal-cord injuries

5.3.5.2 Amputees

5.3.5.3 Cerebral palsy

5.3.5.4 Visual impairment

5.3.5.5 Intellectual disabilities

5.3.5.6 Les autres

5.3.6 Tips for More Effective Programming

Index

xi

422

423

427

427

427

429

429

429

430

430

431

431

432

432

432

433

434

434

435

435

435

435

435

441

441

441

442

443

443

443

445

446

447

448

449

449

453

10/19/2010 10:00:57 AM

ftoc.indd xii

10/19/2010 10:00:57 AM

Foreword by Sir Clive Woodward

High-level performance may seem easy to sport fans. Coaches

and athletes know very well that it is very difficult to achieve.

Winning does not happen in a straight line. It is the result of

incredible efforts, dedication, passion, but also the result of the

willingness to learn something new every day in every possible

field which can help improve performance.

Strength and conditioning is fundamental for preparing athletes to perform at their best. It is also important to provide

better quality of life in special populations and improve fitness.

Scientific efforts in this field have improved enormously our

understanding of various training methods and nutritional interventions to maximize performance. Furthermore, due to the

advancement in technology, we are nowadays capable of measuring in real time many things able to inform the coach on the

best way to improve the quality of the training programmes.

Winning the World Cup in 2003 was a great achievement.

And in my view the quality of our strength and conditioning

programme was second to none thanks to the ability of our staff

to translate the latest scientific knowledge into innovative practical applications. The success of Team GB in Beijing has also

been influenced by the continuous advancement of the strength

and conditioning profession in the UK as well as the ability of

our practitioners to continue their quest for knowledge in this

fascinating field.

Now, even better and more information is available to

coaches, athletes, sports scientists and sports medicine professionals willing to learn more about the field of strength and

conditioning. Strength and Conditioning: Biological Principles

and Practical Applications is a must read for everyone serious

about this field. The editors, Dr Marco Cardinale, Dr Robert

fbetw.indd xiii

Newton and Dr Kazunori Nosaka are world leaders in this field

and have collected an outstanding list of authors for all the

chapters. Great scientists have produced an incredible resource

to provide the reader with all the details needed to understand

more about the biology of strength and conditioning and the

guidance to pick the appropriate applications when designing

training programmes.

When a group of sports scientific leaders from all over the

world come together to produce a book about the human body

and performance, the reader can be assured the material is at

the leading edge of sports science. Success in sport is nowadays

the result of a word class coach working with a world class

athlete surrounded by the best experts possible in various fields.

This does not mean the coach needs to delegate knowledge to

others. A modern coach must be aware of the science to be able

to challenge his/her support team and always stimulate the quest

for best practice and innovation.

The book contains the latest information on many subjects

including overtraining, muscle structure and function and its

adaptive changes with training, hormonal regulation, nutrition,

testing and training planning modalities, and most of all it

provides guidance for the appropriate use of strength and conditioning with young athletes, paralympians and special

populations.

I recommend that you read and use the information in this

book to provide your athletes with the best chances of performing at their best.

Sir Clive Woodward

Director of Sport

British Olympic Association

10/18/2010 5:12:10 PM

fbetw.indd xiv

10/18/2010 5:12:10 PM

Preface

In order to optimise athletic performance, athletes must be

optimally trained. The science of training has evolved enormously in the last twenty years as a direct result of the large

volume of research conducted on specific aspects and thanks to

the development of innovative technology capable of measuring athletic performance in the lab and directly onto the field.

Strength and conditioning is now a well recognised profession

in many countries and professional organisations as well as

academic institutions strive to educate in the best possible way

strength and conditioning experts able to work not only with

elite sports people but also with the general population. Strength

and conditioning is now acknowledged as a critical component

in the development and management of the elite athlete as well

as broad application of the health and fitness regime of the

general public, special populations and the elderly. Strength and

conditioning it is in fact one of the main ways to improve health

and human performance for everyone.

The challenge for everyone is to determine the appropriate

type of training not only in terms of exercises and drills used,

but most of all, to identify and understand the biological consequences of various training stimuli. Understanding how to

apply the correct modality of exercise, the correct volume and

intensity and the correct timing of various interventions is it in

fact the “holy grail” of strength and conditioning. The only way

to define it is therefore to understand more and more about the

biological principles that govern human adaptations to such

stimuli, as well as ways to measure and monitor specific adaptations to be able to prescribe the most effective and safe way of

exercising. Modern advancements in molecular biology are

now helping us understand with much greater insight how

muscle adapts to various training and nutritional regimes.

Technology solutions help us in measuring many aspects of

human performance as it happens. We now have more advanced

capabilities for prescribing “evidence-based” strength and conditioning programmes to everyone, from the general population

to the elite athlete. Our aim with this book is to collect all the

most relevant and up to date information on this topic as written

by World leaders in this field and provide a comprehensive

resource for everyone interested in understanding more about

this fascinating field.

We have structured the book to provide a continuum of

information to facilitate its use in educational settings as well

as a key reference for strength and conditioning professionals

and the interested lay public. In Section 1 we present the

biological aspects of strength and conditioning. How muscles,

bones and tendons work, how neural impulses allow muscle

activity, how genetics and bioenergetics affect muscle function

and how the cardiorespiratory system works. In section 2 we

present the latest information on how various systems respond

fpref.indd xv

and adapt to various strength and conditioning paradigms to

provide a better understanding of the implications of strength

and conditioning programmes on human physiology. Section

3 provides a detailed description of various modalities to

measure and monitor the effectiveness of strength and conditioning programmes as well as identifying ways for improving strength and conditioning programme prescriptions. Section

4 provides the latest information on practical applications and

nutritional considerations to maximise the effectiveness of

strength and conditioning programmes. Finally section 5 provides the latest guidelines to use strength and conditioning

in various populations with the safest and most effective

progressions.

The way the material has been presented varies among the

chapters. We wanted our contributors to present their area of

expertise for a varied audience ranging from sports scientists to

coaches to postgraduate students. Authors from many countries

have contributed to this book and whatever the style has been,

we are confident the material can catch the attention of every

reader.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The editors would like to thank Nicola Mc Girr, Izzy Canning,

Fiona Woods, Gill Whitley the wonderful people in the John

Wiley & Sons, Ltd. for the continuous support, guidance and

help to make this book happen.

Marco Cardinale would like to thank the numerous colleagues contributing to this book as well as the coaches, athletes

and sports scientists which over the years contributed to the

development of strength and conditioning. Thank you, my dear

wife Daniela and son Matteo for your love and support over the

years and for putting up with my odd schedules and moods over

the preparation of this project.

Robert Newton acknowledges the fantastic collaborators

that he has had the honour to work with over the past three

decades and the dedicated and hardworking students and postdocs that he has been privileged to mentor. Thank you, my dear

wife Lisa and daughter Talani for all your support and patience

through my obsession with research and teaching.

Ken Nosaka appreciates the opportunity to make this book

with many authors, Marco, Rob, and the wonderful people in

the John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. I have experienced how challenging it is to edit a book and to make an ideal book, but it was a

good lesson. Because of many commitments, I have a limited

time with my wife Kaoru and daughter Cocolo. I am so sorry,

but your support and understanding are really appreciated, and

would like to tell you that you make my life valuable.

10/18/2010 5:12:12 PM

fpref.indd xvi

10/18/2010 5:12:12 PM

List of Contributors

Per Aagaard

Institute of Sports Science and Clinical Biomechanics,

University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

Prue Cormie

School of Exercise, Biomedical and Health Sciences,

Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, WA, Australia

Chris R. Abbiss

School of Exercise, Biomedical and Health

Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup,

WA, Australia

Blair Crewther

Imperial College, Institute of Biomedical Engineering,

London UK

Tim Ackland

School of Sport Science, Exercise and Health,

University of Western Australia, WA, Australia

Jesper L. Andersen

Institute of Sports Medicine Copenhagen,

Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark

David Bishop

Institute of Sport, Exercise and Active Living (ISEAL),

School of Sport and Exercise Science,Victoria

University, Melbourne, Australia

Anthony Blazevich

School of Exercise, Biomedical and Health Sciences,

Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, WA, Australia

Marco Cardinale

British Olympic Medical Institute, Institute of Sport

Exercise and Health, University College London,

London, UK; School of Medical Sciences, University of

Aberdeen, Aberdeen, Scotland, UK

Christian Cook

United Kingdom Sport Council, London, UK

Matthew Cook

English Institute of Sport, Manchester, UK

Stuart J. Cormack

Essendon Football Club, Melbourne, Australia

flast.indd xvii

Paul Davies

English Institute of Sport, Bisham Abbey Performance

Centre, Marlow, Bucks, UK

Vincenzo Denaro

Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery,

Campus Bio-Medico University, Rome, Italy

Kevin De Pauw

Department of Human Physiology and Sports

Medicine, Faculteit LK, Vrije Universiteit Brussel,

Brussels, Belgium

Fred J. DiMenna

School of Sport and Health Sciences, University of

Exeter, Exeter, UK

Avery D. Faigenbaum

Department of Health and Exercise Science, The

College of New Jersey, Ewing, NJ, USA

Marco Gazzoni

LISiN, Dipartimento di Elettronica, Politecnico di

Torino, Torino, Italy

Olivier Girard

ASPETAR – Qatar Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine

Hospital, Doha, Qatar

Umile Giuseppe Longo

Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery,

Campus Bio-Medico University, Rome, Italy

10/18/2010 5:12:12 PM

xviii

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

Albert Gollhofer

Institute of Sport and Sport Science, University of

Freiburg, Germany

Thomas Muehlbauer

Institute of Exercise and Health Sciences,

University of Basel, Switzerland

Urs Granacher

Institute of Sport Science, Friedrich Schiller University,

Jena, Germany

Marco V. Narici

Institute for Biomedical Research into Human

Movement and Health (IRM), Manchester

Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK

Stuart Gray

School of Medical Sciences, College of Life

Sciences and Medicine, University of Aberdeen,

Aberdeen, UK

Markus Gruber

Department of Training and Movement Sciences,

University of Potsdam, Germany

Mark Jarvis

English Institute of Sport, Birmingham, UK

Andrew M. Jones

School of Sport and Health Sciences, University of

Exeter, Exeter, UK

Arimantas Lionikas

School of Medical Sciences, College of Life Sciences

and Medicine, University of Aberdeen,

Aberdeen, UK

Nicola A. Maffiuletti

Neuromuscular Research Laboratory, Schulthess

Clinic, Zurich, Switzerland

Robert U. Newton

School of Exercise, Biomedical and Health

Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup,

WA, Australia

Kazunori Nosaka

School of Exercise, Biomedical and Health

Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup,

WA, Australia

Jeremiah J. Peiffer

Murdoch University, School of Chiropractic and

Sports Science, Murdoch, WA, Australia

Alberto Rainoldi

Motor Science Research Center, University School

of Motor and Sport Sciences, Università degli Studi,

di Torino, Torino, Italy

Aivaras Ratkevicius

School of Medical Sciences, College of Life Sciences

and Medicine, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK

Nicola Maffulli

Centre for Sports and Exercise Medicine, Queen

Mary University of London, Barts and The London

School of Medicine and Dentistry, Mile End Hospital,

London, UK

Jörn Rittweger

Institute for Biomedical Research into Human

Movement and Health, Manchester Metropolitan

University, Manchester, UK; Institute of Aerospace

Medicine, German Aerospace Center (DLR),

Cologne, Germany

Constantinos N. Maganaris

Institute for Biomedical Research into Human

Movement and Health (IRM), Manchester

Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK

William A. Sands

Monfort Family Human Performance Research

Laboratory, Mesa State College – Kinesiology,

Grand Junction, CO, USA

Ron J. Maughan

School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences,

Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK

Andreas Schlumberger

EDEN Reha, Rehabilitation Clinic, Donaustauf,

Germany

Michael R. McGuigan

New Zealand Academy of Sport North Island,

Auckland, New Zealand; Auckland University of

Technology, New Zealand

Christopher S. Shaw

School of Sport and Exercise Sciences, The University

of Birmingham, UK

Romain Meeusen

Department of Human Physiology and Sports

Medicine, Faculteit LK, Vrije Universiteit Brussel,

Brussels, Belgium

flast.indd xviii

Jeremy Sheppard

Queensland Academy of Sport, Australia; School of

Exercise, Biomedical and Health Sciences, Edith

Cowan University, Joondalup,

WA, Australia

10/18/2010 5:12:12 PM

CONTRIBUTORS

xix

Matt Spencer

Physiology Unit, Sport Science Department, ASPIRE,

Academy for Sports Excellence, Doha, Qatar

Wolfgang Taube

Unit of Sports Science, University of Fribourg,

Switzerland

Filippo Spiezia

Department of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery,

Campus Bio-Medico University, Rome, Italy

Kevin D. Tipton

School of Sports Sciences, University of Stirling,

Stirling, Scotland, UK

Arthur Stewart

Centre for Obesity Research and Epidemiology,

Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, UK

Valmor Tricoli

Department of Sport, School of Physical Education

and Sport, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Margaret E. Stone

Center of Excellence for Sport Science and Coach

Education, East Tennessee State University, Johnson

City, TN, USA

Henning Wackerhage

School of Medical Sciences, College of Life Sciences

and Medicine, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK

Michael H. Stone

Center of Excellence for Sport Science and Coach

Education, East Tennessee State University, Johnson

City, TN, USA; Department of Physical Education,

Sport and Leisure Studies,University of Edinburgh,

Edinburgh, UK; Edith Cowan University, Perth,

Australia

flast.indd xix

Warren Young

School of Human Movement and Sport Sciences,

University of Ballarat, Ballarat, Victoria. Australia

10/18/2010 5:12:12 PM

flast.indd xx

10/18/2010 5:12:12 PM

Section 1

Strength and Conditioning Biology

c01.indd 1

10/18/2010 5:11:13 PM

c01.indd 2

10/18/2010 5:11:13 PM

1.1

Skeletal Muscle Physiology

Valmor Tricoli, University of São Paulo, Department of Sport, School of Physical Education and Sport,

São Paulo, Brazil

1.1.1

INTRODUCTION

The skeletal muscle is the human body’s most abundant tissue.

There are over 660 muscles in the body corresponding to

approximately 40–45% of its total mass (Brooks, Fahey and

Baldwin, 2005; McArdle, Katch and Katch, 2007). It is estimated that 75% of skeletal muscle mass is water, 20% is

protein, and the remaining 5% is substances such as salts,

enzymes, minerals, carbohydrates, fats, amino acids, and highenergy phosphates. Myosin, actin, troponin and tropomyosin

are the most important proteins.

Skeletal muscles play a vital role in locomotion, heat production, support of soft tissues, and overall metabolism. They

have a remarkable ability to adapt to a variety of environmental

stimuli, including regular physical training (e.g. endurance or

strength exercise) (Aagaard and Andersen, 1998; Andersen

et al., 2005; Holm et al., 2008; Parcell et al., 2005), substrate

availability (Bohé et al., 2003; Kraemer et al., 2009; Phillips,

2009; Tipton et al., 2009), and unloading conditions (Alkner

and Tesch, 2004; Berg, Larsson and Tesch, 1997; Caiozzo

et al., 2009; Lemoine et al., 2009; Trappe et al., 2009).

This chapter will describe skeletal muscle’s basic structure

and function, contraction mechanism, fibre types and hypertrophy. Its integration with the neural system will be the focus of

the next chapter.

1.1.2 SKELETAL MUSCLE

MACROSTRUCTURE

Skeletal muscles are essentially composed of specialized contracting cells organized in a hierarchical fashion supported by

a connective tissue framework. The entire muscle is surrounded

by a layer of connective tissue called fascia. Underneath the

fascia is a thinner layer of connective tissue called epimysium

which encloses the whole muscle. Right below is the perimysium, which wraps a bundle of muscle fibres called fascicle (or

fasciculus), thus; a muscle is formed by several fasciculi.

Lastly, each muscle fibre is covered by a thin sheath of collagenous connective tissue called endomysium (Figure 1.1.1).

Strength and Conditioning – Biological Principles and Practical Applications

© 2011 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

c01.indd 3

Directly beneath the endomysium lies the sarcolemma, an

elastic membrane which contains a plasma membrane and a

basement membrane (also called basal lamina). Sometimes, the

term sarcolemma is used as a synonym for muscle-cell plasma

membrane. Among other functions, the sarcolemma is responsible for conducting the action potential that leads to muscle

contraction. Between the plasma membrane and basement

membrane the satellite cells are located (Figure 1.1.2). Their

regenerative function and possible role in muscle hypertrophy

will be discussed later in this chapter.

All these layers of connective tissue maintain the skeletal

muscle hierarchical structure and they combine together to form

the tendons at each end of the muscle. The tendons attach

muscles to the bones and transmit the force they generate to the

skeletal system, ultimately producing movement.

1.1.3 SKELETAL MUSCLE

MICROSTRUCTURE

Muscle fibres, also called muscle cells or myofibres, are long,

cylindrical cells 1–100 μm in diameter and up to 30–40 cm in

length. They are made primarily of smaller units called myofibrils which lie in parallel inside the muscle cells (Figure 1.1.3).

Myofibrils are contractile structures made of myofilaments

named actin and myosin. These two proteins are responsible for

muscle contraction and are found organized within sarcomeres

(Figure 1.1.3). During skeletal muscle hypertrophy, myofibrils

increase in number, enlarging cell size.

A unique characteristic of muscle fibres is that they are

multinucleated (i.e. have several nuclei). Unlike most body

cells, which are mononucleated, a muscle fibre may have 250–

300 myonuclei per millimetre (Brooks, Fahey and Baldwin,

2005; McArdle, Katch and Katch 2007). This is the result of

the fusion of several individual mononucleated myoblasts

(muscle’s progenitor cells) during the human body’s development. Together they form a myotube, which later differentiates

into a myofibre. The plasma membrane of a muscle cell is often

called sarcolemma and the sarcoplasm is equivalent to its cytoplasm. Some sarcoplasmic organelles such as the sarcoplasmic

reticulum and the transverse tubules are specific to muscle cells.

Marco Cardinale, Rob Newton, and Kazunori Nosaka.

10/21/2010 3:16:19 PM

4

SECTION 1

Fascia

STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING BIOLOGY

Tendon

Endomysium

Basal lamina

Muscle

Plasma membrane

Myonucleus

Epimysium

Muscle Fiber

Satellite cell

Endomysium

Basal lamina

Plasma membrane

(sarcolemma)

Myonucleus

Muscle fiber

Muscle Fiber

Perimysium

Figure 1.1.2 Illustration of a single multinucleated muscle fibre and

satellite cell between the plasma membrane and the basal lamina

Connective tissue

Figure 1.1.1 Skeletal muscle basic hierarchical structure. Adapted

from Challis (2000)

1.1.3.1

Sarcomere and myofilaments

A sarcomere is the smallest functional unit of a myofibre and

is described as a structure limited by two Z disks or Z lines

(Figure 1.1.3). Each sarcomere contains two types of myofilament: one thick filament called myosin and one thin filament

called actin. The striated appearance of the skeletal muscle is

the result of the positioning of myosin and actin filaments inside

each sarcomere. A lighter area named the I band is alternated

with a darker A band. The absence of filament overlap confers

a lighter appearance to the I band, which contains only actin

filaments, while overlap of myosin and actin gives a darker

appearance to the A band. The Z line divides the I band in two

equal halves; thus a sarcomere consists of one A band and two

half-I bands, one at each side of the sarcomere. The middle of

the A band contains the H zone, which is divided in two by the

M line. As with the I band, there is no overlap between thick

and thin filaments in the H zone. The M line comprises a

number of structural proteins which are responsible for anchoring each myosin filament in the correct position at the centre of

the sarcomere.

On average, a sarcomere that is between 2.0 and 2.25 μm

long shows optimal overlap between myosin and actin filaments, providing ideal conditions for force production. At

lengths shorter or larger than this optimum, force production is

compromised (Figure 1.1.4).

c01.indd 4

The actin filament is formed by two intertwined strands (i.e.

F-actin) of polymerized globular actin monomers (G-actin).

This filament extends inward from each Z line toward the centre

of the sarcomere. Attached to the actin filament are two regulatory proteins named troponin (Tn) and tropomyosin (Tm) which

control the interaction between actin and myosin. Troponin is a

protein complex positioned at regular intervals (every seven

actin monomers) along the thin filament and plays a vital role in

calcium ion (Ca++) reception. This regulatory protein complex

includes three components: troponin C (TnC), which binds

Ca++, troponin T (TnT), which binds tropomyosin, and troponin

I (TnI), which is the inhibitory subunit. These subunits are in

charge of moving tropomyosin away from the myosin binding

site on the actin filament during the contraction process.

Tropomyosin is distributed along the length of the actin filament in the groove formed by two F-actin strands and its main

function is to inhibit the coupling between actin and myosin

filaments from blocking active actin binding sites (Figure 1.1.5).

The thick filament is made mostly of myosin protein. A

myosin molecule is composed of two heavy chains (MHCs) and

two pairs of light chains (MLCs). It is the MHCs that determines muscle fibre phenotype. In mammalian muscles, the

MHC component exists in four different isoforms (types I, IIA,

IIB, and IIX), whereas the MLCs can be separated into two

essential LCs and two regulatory LCs. Myosin heavy and light

chains combine to fine tune the interaction between actin and

myosin filaments during muscle contraction. A MHC is made

of two distinct parts: a head (heavy meromyosin) and a tail

(light meromyosin), in a form that may be compared to that of

a golf club (Figure 1.1.6).

Approximately 300 myosin molecules are arranged tail-totail to constitute each thick filament (Brooks, Fahey and

Baldwin, 2005). The myosin heads protrude from the filament;

10/18/2010 5:11:13 PM

CHAPTER 1.1

Muscle fibre

Dark

A band

SKELETAL MUSCLE PHYSIOLOGY

5

Light

I band

Myofibril

Section

of a myofibril

A band I band

Z disc

Actin: Thin filament

Myosin: Thick filament

Sarcomere

Cross-bridges

M line

A band

I band

Z disc

Tension (percent of maximum)

Figure 1.1.3 Representation of a muscle fibre and myofibril showing the structure of a sarcomere with actin and myosin filaments. Adapted

from Challis (2000)

100

80

60

40

20

0

Optimal Length

1.2 μm

2.1 μm 2.2 μm

3.6 μm

Sarcomere Length

Figure 1.1.4 Skeletal muscle sarcomere length–tension relationship

c01.indd 5

10/18/2010 5:11:13 PM

6

SECTION 1

STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING BIOLOGY

Myosin heavy chain

G actin

actin-binding site

Troponin I

Myosin head

mATPase

Troponin C

Myosin tail

F actin

Troponin T

Tropomyosin

Ca++

Tn T

Myosin Filament

Tn C

Tn I

Actin

Myosin

active binding site

Figure 1.1.5 Schematic drawing of part of an actin filament

showing the interaction with tropomyosin and troponin complex

Figure 1.1.6 Schematic organization of a myosin filament, myosin

heavy chain structure, and hexagonal lattice arrangement between

myosin and actin filaments

Vinculin

α-integrin

β-integrin

Actin filament

Myosin

filament

Z disk

M line

C-protein

Desmin

Titin

α-actinin

Z disk

Nebulin

Figure 1.1.7 Illustration of the structural proteins in the sarcomere

each is arranged in a 60 ° rotation in relation to the preceding

one, giving the myosin filament the appearance of a bottle

brush. Each myosin head attaches directly to the actin filament

and contains ATPase activity (see Section 1.1.5). Actin and

myosin filaments are organized in a hexagonal lattice, which

means that each myosin filament is surrounded by six actin filaments, providing a perfect match for interaction during contraction (Figure 1.1.6).

A large number of other proteins can be found in the

interior of a muscle fibre and in sarcomeres; these constitute

the so-called cytoskeleton. The cytoskeleton is an intracellular

system composed of intermediate filaments; its main functions

c01.indd 6

are to (1) provide structural integrity to the myofibre, (2) allow

lateral force transmissions among adjacent sarcomeres, and

(3) connect myofibrils to the cell’s plasma membrane. The

following proteins are involved in fulfilling these functions

(Bloch and Gonzalez-Serratos, 2003; Hatze, 2002; Huijing,

1999; Monti et al., 1999): vinculin, α- and β-integrin (responsible for the lateral force transmission within the fibre), dystrophin (links actin filaments with the dystroglycan and

sarcoglycan complexes, which are associated with the sarcolemma and provide an extracellular connection to the basal

lamina and the endomysium), α-actinin (attaches actin

filaments to the Z disk), C protein (maintains the myosin

10/18/2010 5:11:14 PM

CHAPTER 1.1

SKELETAL MUSCLE PHYSIOLOGY

7

Plasma membrane (sarcolemma)

Action potential

Lateral sacs

Myofibrils

Ca++

Transverse tubule

Ca++

Sarcoplasmic reticulum

Triad

Figure 1.1.8 Representation of the transverse tubules (T tubules) and sarcoplasmic reticulum system

tails in a correct spatial arrangement), nebulin (works as a

ruler, assisting the correct assembly of the actin filament),

titin (contributes to secure the thick filaments to the Z lines),

and desmin (links adjacent Z disks together). Some of these

proteins are depicted in Figure 1.1.7.

1.1.3.2 Sarcoplasmic reticulum and

transverse tubules

The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) of a myofibre is a specialized

form of the endoplasmic reticulum found in most human body

cells. Its main functions are (1) intracellular storage and (2)

release and uptake of Ca++ associated with the regulation of

muscle contraction. In fact, the release of Ca++ upon electrical

stimulation of the muscle cell plays a major role in excitation–

contraction coupling (E-C coupling; see Section 1.1.4). The SR

can be divided into two parts: (1) the longitudinal SR and (2)

the junctional SR (Rossi and Dirksen, 2006; Rossi et al., 2008).

The longitudinal SR, which is responsible for Ca++ storage and

uptake, comprises numerous interconnected tubules, forming an

intricate network of channels throughout the sarcoplasm and

around the myofibrils. At specific cell regions, the ends of the

longitudinal tubules fuse into single dilated sacs called terminal

cisternae or lateral sacs. The junctional SR is found at the junction between the A and the I bands and represents the region

responsible for Ca++ release (Figure 1.1.8).

The transverse tubules (T tubules) are organelles that carry

the action potential (electrical stimulation) from the sarcolemma surface to the interior of the muscle fibre. Indeed, they

are a continuation of the sarcolemma and run perpendicular to

the fibre orientation axis, closely interacting with the SR. The

association of a T tubule with two SR lateral sacs forms a

structure called a triad which is located near each Z line of a

sarcomere (Figure 1.1.8). This arrangement ensures synchronization between the depolarization of the sarcolemma and the

release of Ca++ in the intracellular medium. It is the passage of

an action potential down the T tubules that causes the release

of intracellular Ca++ from the lateral sacs of the SR, causing

muscle contraction; this is the mechanism referred to as E-C

coupling (Rossi et al., 2008).

c01.indd 7

1.1.4

CONTRACTION MECHANISM

1.1.4.1 Excitation–contraction

(E-C) coupling

A muscle fibre has the ability to transform chemical energy into

mechanical work through the cyclic interaction between actin

and myosin filaments during contraction. The process starts

with the arrival of an action potential and the release of Ca++

from the SR during the E-C coupling. An action potential is

delivered to the muscle cell membrane by a motor neuron

through the release of a neurotransmitter named acetylcholine

(ACh). The release of ACh opens specific ion channels in the

muscle plasma membrane, allowing sodium ions to diffuse

from the extracellular medium into the cell, leading to the

depolarization of the membrane. The depolarization wave

spreads along the membrane and is carried to the cell’s interior

by the T tubules. As the action potential travels down a T

tubule, calcium channels in the lateral sacs of the SR are opened,

releasing Ca++ in the intracellular fluid. Calcium ions bind to

troponin and, in the presence of ATP, start the process of skeletal muscle contraction (Figure 1.1.9).

1.1.4.2 Skeletal muscle contraction

Based on a three-state model for actin activation (McKillop and

Geeves, 1993), the thin filament state is influenced by both Ca++

binding to troponin C (TnC) and myosin binding to actin. The

position of tropomyosin (Tm) on actin generates a blocked, a

closed, or an open state of actin filament activation. When

intracellular Ca++ concentration is low, and thus Ca++ binding

to TnC is low, the thin filament stays in a blocked state because

Tm position does not allow actin–myosin interaction. However,

the release of Ca++ by the SR and its binding to TnC changes

the conformational shape of the troponin complex, shifting the

actin filament from a blocked to a closed state. This transition

allows a weak interaction of myosin heads with the actin filament, but during the closed state the weak interaction between

myosin and actin does not produce force. Nevertheless, the

weak interaction induces further movements in Tm, shifting the

10/18/2010 5:11:14 PM

8

SECTION 1

STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING BIOLOGY

Axon

Vesicles

Mithocondria

Release site

Acetylcholine

Action potential

Sarcoplasmic reticulum

Myofibrils

T tubule

Ca++ release

Troponin complex

Actin filament

Myosin filament

Tropomyosin

active binding

site

Figure 1.1.9 Excitation–contraction coupling and the sequence of events that will lead to skeletal muscle contraction

Myosin Filament

Myosin head

Open state (attached)

Actin Filament

Actin binding site

ATP

Detached

ADP + Pi

ATP hydrolysis

Release of Pi

Power stroke

Open state (attached)

Figure 1.1.10 Cyclic process of muscle contraction

c01.indd 8

10/18/2010 5:11:14 PM

CHAPTER 1.1

1.1.5

MUSCLE FIBRE TYPES

The skeletal muscle is composed of a heterogeneous mixture of

different fibre types which have distinct molecular, metabolic,

structural, and contractile characteristics, contributing to a

range of functional properties. Skeletal muscle fibres also have

an extraordinary ability to adapt and alter their phenotypic

profile in response to a variety of environmental stimuli.

Muscle fibres defined as slow, type I, slow red or slow

oxidative have been described as containing slow isoform contractile proteins, high volumes of mitochondria, high levels of

myoglobin, high capillary density, and high oxidative enzyme

capacity. Type IIA, fast red, fast IIA or fast oxidative fibres

have been characterized as fast-contracting fibres with high

oxidative capacity and moderate resistance to fatigue. Muscle

fibres defined as type IIB, fast white, fast IIB (or IIx), or fast

c01.indd 9

9

ATPase activity (mmol l–1s–1)

Figure 1.1.11 Photomicrograph showing three different muscle fibre

types

0.5

Shortening velocity (a.u.)

actin filament from the closed to the open state, resulting in a

strong binding of myosin heads. In the open state, a high affinity

between the myosin heads and the actin filament provides an

opportunity to force production.

The formation of the acto-myosin complex permits the

myosin head to hydrolyse a molecule of ATP and the free

energy liberated is used to produce mechanical work (muscle

contraction) during the cross-bridge power stroke (Vandenboom,

2004). Cross-bridges are projections from the myosin filament

in the region of overlap with the actin filament. The release of

ATP hydrolysis byproducts (Pi and ADP) induces structural

changes in the acto-myosin complex that promote the crossbridge cycle of attachment, force generation, and detachment.

The force-generation phase is usually called the ‘power stroke’.

During this phase, actin and myosin filaments slide past each

other and the thin filaments move toward the centre of the

sarcomere, causing its shortening (Figure 1.1.10). Each crossbridge power stroke produces a unitary force of 3–4 pico

Newtons (1 pN = 10−12 N) over a working distance of 5–15

nanometres (1 nm = 10−9 m) against the actin filament (Finer,

Simmons and Spudich, 1994). The resulting force and displacement per cross-bridge seem extremely small, but because billions of cross-bridges work at the same time, force output and

muscle shortening can be large.

Interestingly, the myosin head retains high affinity for only

one ligand (ATP or actin) at a time. Therefore, when an ATP

molecule binds to the myosin head it reduces myosin affinity

for actin and causes it to detach. After detachment, the myosin

head rapidly hydrolyses the ATP and uses the free energy to

reverse the structural changes that occurred during the power

stroke, and then the system is ready to repeat the whole cycle

(Figure 1.1.10). If ATP fails to rebind (or ADP release is inhibited), a ‘rigour ’ cross-bridge is created, which eliminates the

possibility of further force production. Thus, the ATP hydrolysis cycle is associated with the attachment and detachment of

the myosin head from the actin filament (Gulick and Rayment,

1997). If the concentration of Ca++ returns to low levels, the

muscle is relaxed by a reversal process that shifts the thin filament back toward the blocked state.

SKELETAL MUSCLE PHYSIOLOGY

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

I

IIA

IIA-B

IIB

Figure 1.1.12 Representation of the relationship between skeletal

muscle fibre type, mATPase activity, and muscle shortening velocity

glycolytic present low mitochondrial density, high glycolytic

enzyme activity, high myofibrilar ATPase (mATPase) activity,

and low resistance to fatigue (Figure 1.1.11).

Several methods, including mATPase histochemistry,

immunohistochemistry, and electrophoretic analysis of myosin

heavy chain (MHC) isoforms, have been used to identify myofibre types. The histochemical method is based on the differences

in the pH sensitivity of mATPase activity (Brooke and Kaiser,

1970). Alkaline or acid assays are used to identify low or high

mATPase activity. An ATPase is an enzyme that catalyses the

hydrolysis (breakdown) of an ATP molecule. There is a strong

correlation between mATPase activity and MHC isoform

(Adams et al., 1993; Fry, Allemeier and Staron, 1994; Staron,

1991; Staron et al., 2000) because the ATPase is located at the

heavy chain of the myosin molecule. This method has been used

in combination with physiological measurements of contractile

speed; in general the slowest fibres are classified as type I

(lowest ATPase activity) and the fastest as type IIB (highest

ATPase activity), with type IIA fibres expressing intermediate

values (Figure 1.1.12). The explanation for these results is that

10/18/2010 5:11:14 PM

10

SECTION 1

STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING BIOLOGY

the velocity of the interaction between myosin and actin depends

on the speed with which the myosin heads are able to hydrolyse

ATP molecules (see Section 1.1.4).

Immunohistochemistry explores the reaction of a specific

antibody against a target protein isoform. In this method,

muscle fibre types are determined on the basis of their immunoreactivity to antibodies specific to MHC isoforms. An electrophoretic analysis is a fibre typing method in which an

electrical field is applied to a gel matrix which separates MHC

isoforms according to their molecular weight and size (MHCIIb

is the largest and MHCI is the smallest). Because of the difference in size, MHC isoforms migrate at different rates through

the gel. Immunohistochemical and gel electrophoresis staining

procedures are applied in order to visualize and quantify MHC

isoforms.

Independent of the method applied, the results have revealed

the existence of ‘pure’ and ‘hybrid’ muscle fibre types (Pette,

2001). A pure fibre type contains only one MHC isoform,

whereas a hybrid fibre expresses two or more MHC isoforms.

Thus, in mammalian skeletal muscles, four pure fibre types can

be found: (1) slow type I (MHCIβ), (2) fast type IIA (MHCIIa),

(3) fast type IID (MHCIId), and (4) fast type IIB (MHCIIb)

(sometimes called fast type IIX fibres) (Pette and Staron, 2000).

Actually, type IIb MHC isoform is more frequently found in

rodent muscles, while in humans type IIx is more common

(Smerdu et al., 1994).

Combinations of these major MHC isoforms occur in hybrid

fibres, which are classified according to their predominant

isoform. Therefore, the following hybrid fibre types can be

distinguished: type I/IIA, also termed IC (MHCIβ > MHCIIa);

type IIA/I, also termed IIC (MHCIIa > MHCIβ); type IIAD

(MHCIIa > MHCIId); type IIDA (MHCIId > MHCIIa); type

IIDB (MHCIId > MHCIIb); and type IIBD (MHCIIb > MHCIId)

(Pette, 2001). All these different combinations of MHCs contribute to generating the continuum of muscle fibre types represented below (Pette and Staron, 2000):

TypeI ↔ TypeIC ↔ TypeIIC ↔ TypeIIA ↔ TypeIIAD ↔

TypeIIDA ↔ TypeIID ↔ TypeeIIDB ↔ TypeIIBD ↔ TypeIIB

Despite the fact that chronic physical exercise, involving

either endurance or strength training, appears to induce transitions in the muscle fibre type continuum, MHC isoform changes

are limited to the fast fibre subtypes, shifting from type IIB/D

to type IIA fibres (Gillies et al., 2006; Holm et al., 2008;

Putman et al., 2004).The reverse transition, from type IIA to

type IIB/D, occurs after a period of detraining (Andersen and

Aagaard, 2000; Andersen et al., 2005). However, it is still

controversial whether training within physiological parameters

can induce transitions between slow and fast myosin isoforms

(Aagaard and Thorstensson, 2003). The amount of hybrid fibre

increases in transforming muscles because the coexistence of

different MHC isoforms in a myofibre leads it to adapt its phenotype in order to meet specific functional demands.

How is muscle fibre type defined? It appears that even in

foetal muscle different types of myoblast exist and thus it is

likely that myofibres have already begun their differentiation

into different types by this stage (Kjaer et al., 2003);

c01.indd 10

innervation, mechanical loading or unloading, hormone profile,

and ageing all play a major role in phenotype alteration.

The importance of innervation in the determination of specific myofibre types was demonstrated in a classic experiment

of cross-reinnervation (for review see Pette and Vrbova, 1999):

fast muscle phenotype became slow once reinnervated by a

slow nerve, while a slow muscle became fast when reinnervated