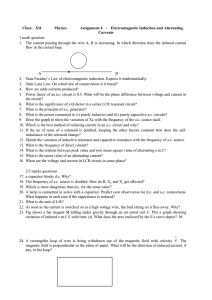

Republic of the Philippines BULACAN STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING City of Malolos, Bulacan CIRCUITS 2 LABORATORY MANUAL Names: _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Section: Instructor: Score: Date: Engr. Diane H. Villanueva Capacitive Reactance ACTIVITY No. 4 OBJECTIVES To examine the capacitive reactance and its relationship to capacitance and frequency, including a plot of capacitive reactance versus frequency. INTRODUCTION The current – voltage characteristic of a capacitor is unlike that of typical resistors. While resistors show a constant resistance value over a wide range of frequencies, the equivalent ohmic value for a capacitor, known as capacitive reactance, is inversely proportional to frequency. The capacitive reactance may be computed via the formula: 𝑋𝐶 = −𝑗 1 2𝜋𝑓𝐶 The magnitude of capacitive reactance may be determined experimentally by feeding a capacitor a known current, measuring the resulting voltage, and dividing the two, following Ohm’s law. This process may be repeated across a range of frequencies to obtain a plot of capacitive reactance versus frequency. An AC current source may be approximated by placing a large resistance in series with an AC voltage, the resistance being considerably larger than the maximum reactance expected. EQUIPMENT AND MATERIALS AC function generator (1) 1 μF capacitor Oscilloscope (1) 2.2 μF capacitor Digital Multimeter (1) 10 kΩ resistor SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM Figure 4.1 Series RC Circuit PROCEDURE 1. Using Figure 4.1 with Vin = 10 V p-p and R = 10 kΩ, and assuming that the reactance of the capacitor is much smaller than 10kΩ and can be ignored, determine the circulating current using measured component values and record in Table 4.1. 2. Build the circuit of Figure 4.1 using R = 10 kΩ, and C = 1 μF. Place one probe across the generator and another across the capacitor. Set the generator to a 200 Hz sine wave and 10 V p-p. Make sure that the Bandwidth Limit of the oscilloscope is engaged for both channels. This will reduce the signal noise and make for more accurate readings. 3. Calculate the theoretical value of Xc and record in Table 4.2. 4. Record the peak-to-peak capacitor voltage and record in Table 4.2. 5. Using the source current from Table 4.1 and the measured capacitor voltage, determine the experimental reactance and record it in Table 4.2. Also compute and record the deviation. 6. Repeat steps three through five for the remaining frequencies of Table 4.2. 7. Replace the 1 μF capacitor with the 2.2 μF unit and repeat steps two through six, recording results in Table 4.3. 8. Using the data of Tables 4.2 and 4.3, create plots of capacitive reactance versus frequency on a graphing paper. Plot to scale. Create separate graphs for 1 μF and 2.2 μF capacitors and label properly. DATA TABLES Table 4.1 Current Source 𝑖𝑠𝑜𝑢𝑟𝑐𝑒 (𝑝−𝑝) Table 4.2 Reactance and Voltage of 1 μF Capacitor Frequency (Hz) 200 400 600 800 1.0 k 1.2 k 1.6 k 2.0 k XC Theory (Ω) VC(p-p) Exp (V) XC Exp (Ω) % Dev XC Exp (Ω) % Dev Table 4.3 Reactance and Voltage of 2.2 μF Capacitor Frequency (Hz) 200 400 600 800 1.0 k 1.2 k 1.6 k 2.0 k XC Theory (Ω) VC(p-p) Exp (V) QUESTIONS 1. What is the relationship between capacitive reactance and frequency? Capacitive reactance (X_C) is inversely proportional to frequency (f), as indicated by the formula: XC= 1 /2πfC1 This implies that when the frequency is raised, capacitive reactance lowers, permitting greater current flow through the capacitor. At lower frequencies, however, the reactance increases, limiting current flow. This is the reason capacitors are usually applied in high-pass filters, allowing high-frequency signals while blocking low-frequency signals. 2. How does capacitive reactance depend on capacitance? The capacitive reactance is also directly proportional to the reciprocal of capacitance (C), and the equation remains the same: XC= 1 /2πfC1 A greater capacitance yields smaller reactance, allowing for greater AC current flow at the same frequency. This is because a capacitor with larger capacitance can supply and accept more charge per cycle. This is important in such applications as power factor correction, where capacitors are 3. Suppose the experiment were to be repeated using frequencies 10 times those of Table 4.2. If the frequency is ten times higher, the capacitive reactance will be reduced by the same factor. Consequently: - The graphs plotted would shift downwards, showing smaller (X_C) values at every frequency point. - The capacitor would carry more current, practically acting as a short circuit at high frequencies. - The voltage drop across the capacitor would be much smaller. - On a linear scale, the inverse relationship would still hold but be compressed towards lower reactance values. - In a log-log graph, the line would curve in the same downward direction but shift appropriately. This is exactly what is desired for signal processing where applications include removing unwanted low-frequency noise using high-pass filters. 4. What if the experiment were done with frequencies 10 times lower than in Table 4.2? If the frequency were lowered by a factor of 10: - The capacitive reactance would go up ten times, so that the capacitor would be even closer to an open circuit for AC. - The graphs plotted would move higher up, on graphs showing very large (X_C) values for all frequencies. - The capacitor would limit the flow of AC current, with greater voltage drop across it. - The curve of reactance on a linear graph would stretch up, highlighting its resistance to lowfrequency signals. - Capacitors are less efficient at passing AC at lower frequencies in real-world circuits, and that is why they are commonly employed to filter out DC signals. This is the reason why capacitors are an important component of low-pass filters, passing lower frequencies while suppressing higher frequencies.