AUTs,and compared reasonably well in the far-out sidelobe region

of the AUTs. We hope you enjoy October's AMTA Corner.

Feedback and Contact Information

Any questions or feedback may be forwarded to me via e­

mail at stephen.schneider@wpafb.af.mil or to Jeff Kemp at

jeff.kemp@gtri.gatech.edu. If you wish to reference other previous

AMTA publications, AMTA members can do so through our

online archive at http://www.amta.org. If you are not a member,

$50.00 and a few mouse clicks will get you registered as a member

today! Both Jeff Kemp and I are open to feedback. Until next time!

Photonic Probes and Advanced (Also

Phaseless) Near-Field Far-Field Techniques

1

1

1

1

2

2

1

A. Capozzo/i , C. Curcio , G. D'Elia , A. Liseno , P. Vinetti , M. Ameya , M. Hirose ,

2

2

S. Kurokawa , and K. Komiyama

lUniversita di Napoli Federico II, Dipartimento di Ingegneria Biomedica, Elettronica e delle Telecomunicazioni (DIBET)

via Claudio 21, 1-80125 Napoli, Italy

Tel: +39-081-7683115; Fax: +39-081-5934448; E-mail: a.capozzoli@unina.it

2Electromagnetic Wave Division, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST)

Tsukuba-shi, 305-8568, Japan

Tel: +81-29-861-5676; Fax.:+81-29-861-3492; E-mail: masa-hirose@aist.go.jp

Abstract

We present innovative near-field test ranges, named compact-near-field (CNF) and very-near-field (VNF). These use photonic

probes, and advanced near-field far-field (NFFF) transformations from amplitude and phase (complex) or phaseless

measurements. The photonic probe allows AUT-probe distances of less than one wavelength. This drastically reduces test­

range and scanner dimensions, improves the signal-to-clutter ratio and the signal-to-noise ratio, and reduces the scanning

area and time. In both the cases of complex and phaseless measurements, the neat-field-to-far-field transformation problem is

properly formulated to further improve the rejection of clutter, noise, and truncation error. The advantages of the compact­

near-field and very-near-field test ranges are discussed and numerically analyzed. Experimental results are presented for both

planar and cylindrical scanning geometries.

Keywords: Antenna measurements; antenna radiation patterns; near-field far-field transformations; photonic sensors; very

near field; compact range; singular value decomposition; singular value optimization; phaseless.

232

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No.5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

1. Introduction

200 �m. Each pair of antenna arms was separated by a gap region

of ) 2 /.lm in width, so that the total length amounted to 2.4 mm.

hotonic probes [1-3] have paved the way to new scenarios in

near-field (NF) antenna characterization [4-6] in terms of per­

formance, cost, and speed. This has been due to their reduced RCS,

dimensions, and weight, the non-invasiveness of dielectric con­

nections, and the possibility of implementing probe arrays [7],

allowing for parallel (faster) acquisition [8].

was based on channel waveguides realized by titanium ( Ti+) in­

diffusion, working at a wavelength of 1.55 /.lm. A silica

(Si02 buffer layer was introduced onto the substrate to allow easier

P

Indeed, to reduce the interactions among the antenna under

test (AUT), the probe, and its mount, the probe and the AUT must

be sufficiently spaced from each other. However, in doing so the

field intensity decreases and its effective support widens. Accord­

ingly, the signal-to-clutter ratio (SCR: the ratio between the signal

of interest and undesired signals due to environmental reflections)

[9J deteriorates the SNR (the ratio between the signal of interest

and the measurement noise) for a fixed AUT input power. Fur­

thermore, larger anechoic environments and scanners are required.

Finally, the truncation error increases if the scanning area is held

constant.

Following [6], in this paper we deal with innovative near­

field test ranges, named the compact-near-field (CNF) and very­

near-field (VNF) ranges. These were developed in the framework

of the cooperation between the Dipartimento di Ingegneria Bio­

medica, Elettronica e delle Telecomunicazioni (DIBET) of the

Universita di Napoli Federico II, Naples, Italy, and the Electro­

magnetic Waves Division at the National Institute of Advanced

Industrial Science and Technology (AIST), Tsukuba, Japan. The

ranges use photonic probes and advanced near-field-to-far-field

(NFFF) transformations [6, 10, ))]. The probe allows distances of

less than one wavelength between the AUT and the probe. This

drastically reduces the test-range and scanner dimensions,

improves signal-to-clutter ratio and SNR, and reduces the scanning

area and time. The near-field-to-far-field transformations exploit

both amplitude and phase (complex) or phaseless measurements

(here for the very first time with photonic probes). In both the

cases, the near-field-to-far-fie1d transformation problem is properly

formulated to further improve the rejection to clutter, noise, and

truncation error.

The advantages of the compact-near-field and very-near-field

ranges are more deeply discussed here as compared to [6]. They

are thoroughly numerically analyzed by pointing out the fruitful­

ness of performing measurements as close as possible to the

radiator in terms of truncation error, of achievable SNR, and of

rms reconstruction error for both complex and phaseless data.

Experimental results are presented for both planar and cylindrical

scanning geometries, also explaining the satisfactory cross-polari­

zation performance of the probe.

The optical circuit, integrated within the probe's substrate,

deposition of the antenna electrodes. The optical circuit imple­

mented a Mach-Zender interferometer by means of channel

waveguides and a single Y-junction. The probe operated in a

reflection mode, exploiting a reflecting coating properly realized

on the terminal face of the substrate. This configuration allowed

using a unique fiber optic for both the uplink and downlink con­

nections to the optical controller. This reduced the perturbations

unavoidably introduced by the use of two connections, especially if

the sensor was integrated into a probe array.

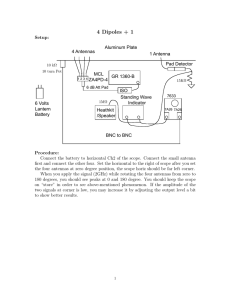

2.2 The Measurement Setups for

Photonic Probe Measurements

For both planar and cylindrical acquisition, the measurement

chain employed can be subdivided into a radio-frequency (RF) part

and an optical part.

The RF part consisted of an Anritsu 37165A vector network

analyzer (VNA) with SM5392 S-parameter test set for planar

measurements. For the cylindrical case, an HP 8719D vector net­

work analyzer, an HP 8348A signal preamplifier, and an HP

84498 power amplifier were used.

The optical part included an NECrrokin OEFS-S I optical

controller, integrating a light source, a circulator, and a

photodetector. An NIT Electronics FAS550DCS optical amplifier

and an Agilent Technologies NIT 427 variable attenuator were

inserted to control the signal power feeding the photodetector.

Finally, the planar scanning was implemented in a semi­

anechoic, planar test facility (the Tokai Techno near-field planar

scanner NAS300), at the Application Technology Labs of Kyoto

Research Park Corp. Kyoto, Japan, kindly made available to the

research team (Figure 2). On the other side, the cylindrical scan­

ning was set up in one of the anechoic-chamber test facilities of

AIST, Tsukuba,Japan (Figure 3).

2. The Photonic Sensor and the

Measurement Setups

2.1 The Probe

The photonic probe was designed at the Electromagnetic

Wave Division of AIST. It consisted of a lithium-niobate

( LiNb03), X-cut crystal wafer, having a thickness of 0.5 mm and

dimensions of 8 mm x 3 mm, with an array antenna printed on it

(Figure I). The array was made up of seven parallel and identically

printed short dipoles, spaced I 00 �m apart from each other. Every

arm of each dipole had a total length of 1.194 mm and a width of

Figure 1. The photonic sensor in front of the tested horn

antenna.

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No.5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

233

pattern (FFP) when either complex or phaseless data were

involved. The purpose of the algorithms was to provide a field rep­

resentation useful to both cases. In particular, the aim was to

improve the robustness against the truncation error, the environ­

mental clutter, and the noise, with further improvements in the

phaseless case in terms of reliability and accuracy. The algorithm

is described by referring to a generic geometry of the acquisition

surfaces, quoting the Appendix for particularizations to the planar

and cylindrical cases.

Let us assume that the AUT lies in the xz plane of a Cartesian

coordinate system Oxyz, and radiates towards the y > 0 half-space,

as shown in Figure 5. The aperture field is assumed to be vanish­

ingly small outside an "effective " aperture, A, contained within the

rectangular

domain,

smallest

(coordinate)

Da

p

Figure 2. The Tokai Techno planar test range.

=[ -aap,aap Jx[ -bap,bap ] centered at O.

For the sake of simplicity, we will refer the discussion to one

Cartesian component of the aperture field (ga

=

Ealz), so that we

can deal with a scalar problem.

The z-component E of the plane-wave spectrum (PWS) can

be expressed as

where JD

""

denotes the Fourier-transform operator limited to Dap.

When the plane-wave spectrum is an essentially finitely supported

Figure 3. The cylindrical range of AIST.

2.3 The Measurement Setup for Open­

Ended-Waveguide Probe Measurements

For cylindrical measurements exploiting (un-flanged) open­

ended waveguides, the indoor testing environment was the anech­

oic chamber designed and realized by MI-Tech [12] for the

Microwave and Millimetre-Wave Lab of DIBET (Figure 4). The

chamber was set up to work in the 900 MHz to 40 GHz frequency

band. It was equipped with both planar and cylindrical scanning

systems, driven by an external MI-4190 controller. The measure­

ments were performed by means of an Anritsu vector network

analyzer 37397C, operating in the 40 MHz to 65 GHz frequency

band.

3. Advanced Near-Field Far-Field

Techniques

3.1 Near-Field Characterization Algorithm

We will now outline the near-field characterization algo­

rithms for aperture antennas. These aimed at retrieving the far-field

234

Figure 4. The cylindrical range of DIBET.

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine. Vol. 52. No.5. October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

z

throughout the paper to a "standard" near-field-to-far-field trans­

formation that obtains the far-field pattern by avoiding the use of

Equation (2).

In the case of phaseless measurements, the anm are searched

for as those coefficients making the squared amplitudes of the cor­

responding theoretical fields on

Sl and S

on

as close as possible to

� ( ):::::;"M

Ei B {.rDup [Ea (�)]}

the measured data. Denoting by

the unknowns, and by

2

anm

=

the matrix of

the (complex) field

=

Si' 'B being the operator connecting the spectrum to the near

field, then the unknown � is obtained by minimizing the objective

functional [II]

(4)

Figure 5. The problem geometry with arbitrary scanning sur­

faces.

where

I .I �( Sj)

is the usual

£.2 norm on Si' i

=

1,2 - say

£.2 (Si) -

i:t? (r) and i:ti (r) are the squared amplitude measurements.

and

function with support n = [-u,u]x[-il, il], then the aperture field

can be expanded as [13, 14]

N-lM-l

Ea(x,z)= L L

n=O m=O

[

]

[

3.2 Advanced Field Sampling

(2)

anm<I>n cx.x <I>m cz'z ,

]

Recently, a new perspective was given to the field-sampling

[ w , w] is the prolate-spheroidal wave function (PSWF)

with

space-bandwidth product

cw'

Cx

uaap' Cz Vhap ,

N [2Cx/1e], and M

[2cz/n], with the symbol [x] denoting the

where <I>i c

=

=

=

and field-reconstruction problems [15]. It is capable of also pro­

viding a measurement strategy for the very-near-field region of the

radiator.

By exploiting the representation in Equation

=

integer part ofx [10, II, 13, 14].

The characterization problem amounts to reconstructing the

E

an from the knowledge of the complex

field acquired over the

m

single surface SI in the case of complex measurements, or of the

squared amplitude,

IEI2,

{(xp,zp )};=I

by

of the E field over two surfaces,

SI and

S2' in the case of phaseless measurements (see Figure 5). Follow­

ing the retrieval of the anm, then the plane-wave spectrum can be

determined from Equation (I), and the far-field pattern can be

{Ep=E(Xp,Zp)}:=1

.Jl. the operator connecting the measured

measurements and according to Equation (2), the unknowns

an

m

locations,

and

letting

be the very-near-field samples (see Fig­

field of the AUT and the anm is described by a proper matrix

r

[10, IS]. Accordingly, for fixed sample number P and locations,

the anm can be recovered from the

Ep

by using the singular-value

decomposition (SVD) approach [lO, IS].

The retrieval of the

field to the plane-wave spectrum, then in the case of complex

sampling

ure 6), the relationship between the sampled field in the very-near­

deduced.

On denoting by

the

(2), on denoting

vided that

a nm

can be reliable and accurate, pro­

r is well-conditioned. On the other hand, the matrix r

is not univocally defined, since it depends on the choice of P and

on the sample distribution. In other words, we have at our disposal

can be determined as

XI

_

. .

.

.

X2

y

XII

XN

• . . . . . . . • . . . . .• . . • . . . . . . . . . •. . . . . . • . . . . . • . • . . . . . . .

(3)

where E is the measured (complex) near field,

:r.-1

is the inverse

o

d

Fourier transform truncated to n, and Ak is the eigenvalue corresponding to <l> k' To emphasize the filtering power of the prolate­

spheroidaJ-wave-function representation in Equation (2), the com­

plex

near-field-to-far-field

transformation

will

be

compared

o

X

Figure 6. Sampling in the reactive region of the AUT.

IEEE Ant9l1nas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No.5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

235

a family of matrices

r with different behavior of the singular val­

ues. The inversion should therefore be performed by exploiting the

element of the family with "the most convenient" singular-value

aperture plane

behavior.

From this point of view, among all the matrices

r and for a

probe

fixed P, it is convenient to choose the locations of the sampling

points providing the "flattest" singular-value behavior. In other

words, for a fixed P and on letting K = min

tional '¥ [10, 15],

{P, M x N} the func­

,

AUT

(5)

evaluating the "area" subtended by the normalized singular values

compact near field

erd erl , is maximized.

(cylindrical or spherical)

measurement surface

The choice of the "optimal" number of samples P can be per­

formed by observing that '¥ admits an interpretation in terms of a

generalized Shannon number [16]. On denoting by '¥ opt

(p) the

optimum of '¥ for a given P, adding further sampling points will

increase '¥ opt

(p) until the maximum amount of information that

Figure 7b. Compact-near-field cylindrical or spherical meas­

urements.

can be gathered from them is reached. Beyond this, no further

information can be acquired by any newly added field sample. This

corresponds to the appearance of very small singular values, and

thus to a "saturation" behavior of '¥ opt

(p) as a function of P [10,

aperture plane

15, 16]. The number, P, at the saturation knee represents the mini­

mum number of samples needed to achieve the information avail­

able on the anm.

probe

AUT aperture

compact near field

cylindrical or spherical

measurement plane

measurement surface

Figure 8. Compact-near-field cylindrical or spherical meas­

urements.

aperture plane

probe

4. Compact Near Field

We now discuss how photonic sensors and proper near-field

processing algorithms enable the implementation of accurate and

reliable compact-near-field setups, thanks also to the possibility of

AUT aperture

performing the measurements under unconventional geometries.

very near field

Indeed, employing such kinds of probes allows longitudinal driv­

ing and the straightforward generalization of the geometries of the

scanning surfaces, trying to minimize the range dimensions and the

truncation error.

To begin with, some examples of unconventional compact­

near-field measurements are illustrated in Figures 7 and 8.

Under planar scanning, the compact-near-field range can be

implemented by drawing the measurement plane in the very close

proximity of

Figure 7a. Compact-near-field planar measurements.

236

a (planar)

aperture antenna (Figure 7a).

When

required, cylindrical or spherical compact-near-field environments

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No.5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

can be also used to test the AUT by means of "planar-cylindrical "

or "planar-spherical " approaches,in order to:

a.

b.

.0

,.-,.

f{3

'"-"'

Limit the data truncation, by encircling the radiator

and/or feeding structures as in the case of retlectors or

retlectarrays, thus avoiding the need for using large

scanning areas (Figure 7b).

Reduce the error due to truncation on the far field (Fig­

ures 7b and 8), by profiting from a proper representa­

tion of equivalent planar-aperture fields.

�

0

.....

ro

u

§

cz:::

.l:l

Z 27

§

r/J

It should be remarked that in the presence of feeding struc­

tures (Figure 7b), the measurement radius of the enclosing surface

can be several wavelengths. On the other hand (Figure 8), the

measurement radius can be of the order of the wavelength or less,

depending on the antenna's size.

The advantages of a compact-near-field test range are first

enlightened numerically. To this end, we here address the case of

planar acquisitions when the AUT simulates the hom antenna con­

sidered also for the experimental test case. The hom had an aper­

ture of 193 mm x 144 mm, a phase center located 290 mm behind

the aperture, and worked at 9 GHz (Scientific Atlanta 12-8-2 stan­

dard-gain hom). For the sake of brevity, the numerical investiga­

tions will be led only in the case of complex acquisitions, since

similar considerations can be extended to the phaseless case.

4.1 Robustness as a Function of

Data Truncation

For a measurement surface fixed in size and moving away

from the AUT, the truncation of the data obviously increases. Fig­

ure 9 reports the data truncation undergone by a planar surface,

260 mm x 180 mm,centered on the AUT's aperture and scanned at

different distances, d, from the AUT ranging over (0.2..1,,20..1,).

Figure 10 shows the percentage rms error as a function of d, fol­

lowing the reconstruction of the far-field pattern by the standard

near-field-to-far-field transformation. On the same figure, the per­

formance achieved by using the filtering power of the prolate­

spheroidal-wave-function representation is also depicted. By com­

paring the two graphs, how a proper expansion of the unknown also in the case of a complex near-field-to-far-field transformation

·

- can be of significant help against data truncation clearly

appeared. In other words, the use of the representation provided a

filtering of the truncation error in the reconstructed far-field pat­

tern.

In order to provide a benchmark of the convenience of com­

pact-near-field systems against truncation, we stress that for the

case above, when the surface was set at d 6..1, (a typical distance

for standard probes), the rms error was 21.3%. To reach the 3%

error corresponding to a distance of 0.4..1" the scanning surface,

still at d 6..1" would have to be extended to 1222 mm x 846 mm,

i.e.,to an overall area that is approximately 22 times larger.

=

=

4.2 Robustness as a Function of

Disturbances

In order to analyze the case above to enlighten the effects of

near-field disturbances on the quality of the far-field pattern, the

,

,

10

dJA

12

,.

16

"

'-50

20

a

.·a

.....

:;E

Figure 9. The SNR (solid) and minimum truncation level (cir­

cles).

30

�

15

dJA

Figure 10. The rms error in the estimation of the far-field pat­

tern amplitude under a standard (solid) and prolate-spher­

oidal-wave-function-based

(circles)

near-field-to-far-field

transformation.

analysis was performed by keeping the scanned area fixed. Fig­

ure II reports a cut along the z direction of the numerically simu­

lated amplitude of the field radiated by the hom at different values

of d. As expected, as long as d increased, the support of the field

broadened and the intensity weakened. Hence, for a measurement

surface fixed in size, moving away from the AUT, both the SNR

and the signal-to-c1utter ratio decreased. In real terms, Figure 9

reports the numerical evaluations of the disturbance (SNR and sig­

nal-to-c1utter ratio): for the sake of simplicity,modeled as additive,

Gaussian, and spatially uncorrelated. Such statistics could be con­

sidered not very realistic to model the signal-to-c1utter ratio, but

this gap will be filled in the subsection devoted to the experimental

results, wherein real cases are considered. (A more-detailed analy­

sis of the signal-to-c1utter-ratio effect in the case of phaseless

acquisitions was reported in the very recent contribution [11].)

By referring to the same case in the previous subsection,Fig­

ure 12 shows the percentage rms error following the reconstruction

of the far field by the standard near-field-to-far-field transforma­

tion, and that achieved by using the prolate-spheroidal-wave-func­

tion representation of the aperture field. Again, the utility of a

proper expansion of the unknown was confirmed.

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No.5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

237

collected over the first of the mentioned surfaces. Good agreement

could be seen between the far-field pattern retrieved from sur­

face #1 and the simulated pattern. Analysis of the algorithm's per­

formance as long as the scanning plane was moved away from the

AUT was reported in [6]. Surfaces #2 and #3 were employed for

the phaseless analysis in the following subsection.

4.4 Experimental Phaseless

Compact Near Field

·��.-----.,�o----��----�----��----,�o-----7,.·

y/'A.

Figure 1 1. The field amplitude radiated by a horn antenna at

different distances.

d. from the aperture: (black) d

=

O.3A;

(blue) d = 4.2A ; (red) d = 8.lA; (green) d = 12A.

In the phaseless case, bounding the test-range dimensions

was even more relevant, since these techniques require larger

measurement volumes, needing two sufficiently spaced scanning

surfaces to provide reliable results. We now show the possibility

and the advantage of implementing compact-near-field phaseless

techniques, again numerically and experimentally.

Resuming the numerical analysis with two planar surfaces,

260 mm x 180 mm in size and located 0.2A and 3A apart from the

aperture, respectively, the rms error equaled 7.1%. On the other

side, when the first surface was at a standard near-field distance

and, in particular, d = 6A, reaching the same rms error was possi­

ble only by considering two planar surfaces 520 mm x 360 mm in

size, and with the second one at d 12A

r--

�

22

'--"

1-0

o

C20

=

(1)

en

.

Figure 13 illustrates a comparison between the cuts along the

E ••

�

Concerning amplitude and phase measurements, a thorough

analysis was already presented in [6].

v axis of the retrieved far-field patterns under complex and phase­

' 6�

,.10L

�=:::;:I=--=::!:::;:'

12

14

Ie

18

�

n

SNR (dB)

�

�

==::-:�o

»

u

Figure 12. The rms error in the estimation of the far-field pat­

tern amplitude under a standard (solid) and prolate-spher­

oidal-wave-function-based

(circles)

near-field-to-far-field

transformation for d = 3A •

less reconstructions, when one of the two surfaces was in the very

near field. The complex near-field-to-far-field transformation was

the same as before when applied to surface # I, while the phaseless

near-field-to-far-field transformation was applied to data from sur­

faces #1 and #2, which were spaced approximately 3.57A apart.

Good agreement could be appreciated between the complex and

phaseless techniques.

5. Very-Near-Field (VNF ) Measurements

We now further enlighten the possibilities of very near field.

By this term, we mean those configurations for which the probe

4.3 Experimental Complex

Compact Near Field

To test the above arguments, we tum attention now to the

experimental analysis. In this, three planar surfaces were scanned

at different distances from the AUT, namely

,.--..., ·10

�.,.

Planar surface # 1, spaced 129 mm ( O.3A) apart from

the AUT and 300 mm x 240 mm in size;

Planar surface #2, spaced 129 mm ( 3.n) apart from

the AUT and 400 mm x 400 mm in size;

Planar surface #3, spaced 295 mm ( 8.9A) apart from

the AUT and 640 mm x 640 mm in size.

Figure 13 shows a comparison among the cuts along the v axis of

the far fields, as evaluated by the prolate-spheroidal-wave-func­

tion-based near-field-to-far-field procedure applied to the data

238

' --�

�2

O'��

�,�-�

�.'�������

��

��--�O�2��O�

�--�

O.�

' --�

v/6

Figure 13. The far-field pattern retrieved from surfaces # 1 and

#2: (black) numerical reference; (red) complex near-field-to­

far field; (blue) phaseless near-field-to-far field.

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No.5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

employed allows performing the acquisitions so close to the AUT

as to acquire information of better quality, or even more informa­

tion than that usually available in standard near-field ranges.

..

·10

First, in phaseless near-field-to-far-field, direct access to the

quantity of interest during the AUT's characterization - namely,

the amplitude of the aperture field - could significantly help the

reconstructions. Indeed, on resuming the last experimental test of

the foregoing section, Figure 14 illustrates the same comparison as

for Figure 13. However, now the situation was when both the pla­

nar surfaces were in the near-field range (surfaces

and #3) with

a spacing of approximately 52, that is, larger than the reciprocal

distance between surfaces I and

As could be seen, the best

agreement between the complex and phaseless near-field-to-far­

field transformations was obtained when one of the two surfaces

was very close to the antenna's aperture.

�.15

'-"

#2

#

·M

�2�� �� �

0 2��0�

�,�-7

A--�

.' --�

O�

. --�

O.��

�.•�-��.•����

viP

Figure 14. The far-field pattern retrieved from surfaces #2 and

#3. (black) numerical reference; (red) complex near-field-to­

far field; (blue) phaseless near-field-to-far field.

#2.

Second, the very-near-field region of the AUT can also con­

vey information about the evanescent (invisible) part of the plane­

wave spectrum, which is to the contrary unavailable under standard

near-field scanning.

6. Experimental Results on a Slot-Array

Antenna and on a Patch Antenna

In this section, we finally present the results obtained in a

cylindrical compact-near-field range.

As a first test case, an array of 13 slots realized in a rectangu­

lar waveguide was considered. The slots were located in alternat­

ing positions with respect to the waveguide's centerline, spaced

2g

from each other ( 2g being the wavelength in the

j2

waveguide). The work was done at X band (in particular, 9.4 GHz)

(Figure 15). To characterize the mentioned antenna, two cylindri­

cal surfaces were acquired by the photonic probe at AIST, with

point coordinates denoted by ( r cos cp, r sin cp, z), radii r = r] = I2

and r = r2 = 5.62, and -

son, scans with a standard open-ended waveguide over two cylin­

drical surfaces with radii r = 1j = I I2, r = r2 = 02 and

Figure 15. The tested slot-array antenna.

-,,/2

viP

Figure 16. The slot array far-field patterns: (black) complex

near-field-to-far field by open-ended-waveguide probe; (red)

near-field-to-far

field

phaseless near-field-to-far field.

by

photonic

probe;

,,12

2

-:;, cp -:;,

were also performed at DIBET. Figure 16 shows

cuts along the v axis of the far-field patterns as retrieved from

complex near-field-to-far-field transformations by the photonic and

the open-ended-waveguide probes, compared to the results

obtained by a phaseless near-field-to-far-field transformation.

Furthermore, Figure 17 depicts the results obtained by complex

near-field-to-far-field transformations from cross-polarized data by

the photonic and the open-ended-waveguide probes. As could be

seen, the cross-polarized results for the two probes were approxi­

mately at the same level (-40 dB) below the retrieved co-polarized

far-field pattern.

..

complex

2.

"/2 -:;, cp -:;, ,,/2. For the sake of compari­

(blue)

Figure 18 shows cuts along the v axis of the far-field pattern

retrieved from a cylindrical scan when the AUT was an array of

four patches, of which only one patch was radiating and the others

were parasitic. A radius of I2 was used for the measurement sur­

face. In more detail, Figure 18 compares the far-field pattern

retrieved by the considered approach with that determined when a

standard near-field-to-far-field transformation from very-near-field

data was considered, and with that obtained when a standard open­

ended-waveguide (open-ended waveguide G) was used, with a

measurement radius of 6.52. The improvement produced by the

adopted prolate-spheroidal-wave-function representation could be

clearly observed.

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No. 5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

239

Future developments branch out in three directions_ First, we

mention the possibility of setting up very fast systems based on

probe arrays. Second, proper very-near-field sampling techniques

should be developed to also profit from the information arising

from the evanescent part of the plane-wave spectrum. Third, the

employed field representation by equivalent planar apertures is not

a limitation, as different (e.g., ellipsoidal) surfaces matching the

antenna's geometry can be employed.

-10

Finally, the system can be extended to spherical scanning

[17]. It can find applications in many other fields, such as security

(intelligence) [18], protection (safety of people and structures),

electromagnetic compatibility [19], and diagnostics (inverse elec­

tromagnetic scattering) [20].

.7�1�--o-:':.•:---:

-o�

. --:!'

-o ..,---JL-o

•

:":

.2-�L-O=-=

. 2'----:

- 0""

A --:':

O .•:--�--':""..J

v/j3

8. Appendix

Figure 17. The slot array far-field patterns. (black) complex

near-field-to-far field by open-ended-waveguide probe and co­

polarized

data;

(red):

complex

near-field-to-far

field

by

8.1 Planar geometry

photonic probe and cross-polarized data; (blue) complex near­

field-to-far field by open-ended-waveguide probe and cross­

The generic surface, Sj, is a portion of a plane y =Yo . The

polarized data.

operator .Jl. particularizes as

E( u, v) = If E( x,Yo,z)e}(ux+vz+wYo)dxdz

.

(6)

s,

On the other side, the operator 'B is

)

(

E x,yo,z = 'B

=

(27r)

n

8.2 Cylindrical Geometry

..

.10 '------'

v/j3

Figure 18. The patch array far-field patterns: (black) standard

near-field-to-far-field

( E) _1-2 If E(u, v)e}(ux+vz+wYo)dudv. (7)

transformation;

(red)

proposed

approach with photonic probe; (blue) open-ended waveguide G

reference.

The generic surface, Sj, is a portion of a cylinder with radius

rj,

(

that

is,

the

) (

scanning

)

points

ture antennas, Ij should be chosen larger than max

ip is strictly limited to

)

•

We discussed the performance of a measurement system

employing some of the recent innovations introduced in near-field

antenna-testing facilities, allowing non-conventional scanning

geometries and accurate data processing. The system is based on a

noninvasive photonic probe, performing acquisitions in the very­

near-field or compact-near-field regions, without significant probe­

AUT coupling. It adopts reliable and accurate algorithms for

antenna characterization from amplitude and phase or phaseless

data. The improvements over standard near-field acqujsitions have

been numerically and experimentally discussed. The setup allows

significant reductions of the dimensions (and costs) of usual near­

field test ranges. The potentials of very-near-field measurements

have been pointed out, along with the satisfactory cross-polarized

isolation of the probe.

240

coordi­

{Gap' hap} , and

(-"/2,,,/2). The operator .Jl. particular­

izes as

( )

sin ()

00

E( u, v = .Jl. E = 4A-.- L fbn

7. Conclusions and Future Developments

have

nates x,y,z = ljcosip,rjsinip,z . As we are dealing with aper-

sm rp n=-oo

(!3 cos(} ) eJn¢, (8)

.

where u = -/3 sin () cos rp, v =/3 cos () , and

h=

�p2 - y2 , and H�2) ( ) is the Hankel function of nth order

.

and second kind.

On the other side, the operator 'B is

(

)

E Ij,z,rp = 'B

( E) If E(u, v)e-}[WiCOS¢+vz+w'isin¢]dudv.

=

n

(10)

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No. 5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

9. References

I. M. Kanda and K. D. Masterson, "Optically Sensed EM-Field

Probes for Pulsed Fields," Proceedings of the IEEE, 80, I, January

1992,pp. 209-215.

2. Z. Fuwen, C. Fushen, and Q. Kun, "An Integrated Electro-Optic

E-Field Sensor with Segmented Electrodes," Microwave and Opti­

cal Technology Letters, 40, 4,February 2004,pp. 302-305.

3. A. Capozzoli, G. D'Elia, M. Iodice, I. Rendina, and P. Vinetti,

"A Photonic Probe for Antenna Measurements," Proceedings of

the 9th International Conference on Electromagnetics in Advanced

Applications (ICEAA05), Turin, Italy,September 12-16,2005, pp.

179-182.

4. M. Hirose, K. Komiyama, J. Ichijoh, and S. Torihata, "Pattern

Measurement of X-Band Standard Gain Hom Antenna Using

Photonic Sensor and Planar Near-Field Scanning Technique," Pro­

ceedings of the 22nd AMTA Symposium, Cleveland, OH, Novem­

ber 3-8,2002,pp. 284-288.

5. M. Hirose, T. Ishizone, and K. Komiyama, "Antenna Pattern

Measurements Using Photonic Sensor for Planar Near-Field Meas­

urement at X Band," IEICE Trans. Commun., E87-B, 3, March

2004,pp. 727-734.

6. A. Capozzoli, C. Curcio, G. D'Elia, A. Liseno, P. Vinetti, M.

Ameya, M. Hirose, S. Kurokawa, and K. Komiyama, "Dielectric

Field Probes for Very-Near-Field and Compact-Near-Field

Antenna Characterization," IEEE Antennas and Propagation

Magazine, 5 1, 5, October 2009,pp. 118-125.

7. 1. C. Bolomey and F. E. Gardiol, Engineering Applications of

the Modulated Scatterer Technique, Norwood, MA, Artech House,

2001.

I I. A. Capozzoli, C. Curcio, G. D'Elia, and A. Liseno, "Phaseless

Antenna Characterization by Effective Aperture Field and Data

Representations," IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propaga­

tion, AP-57, I, January 2009, pp. 215-230.

12. D. W. Hess, C. A. E. Rizzo, and J. Fordham, "Measurement of

Antenna Performance for Active Array Antennas with Spherical

Near-Field Scanning," Proceedings of the lET Seminar on Wide­

band, Multiband Antennas and Arrays for Defence or Civil Appli­

cations, London,UK, March 13,2008.

13. B. R. Frieden, "Evaluation, Design and Extrapolation Methods

for Optical Signals, Based on Use of the Prolate Functions," in E.

Wolf (ed.), Progress in Optics, Volume 9, Amsterdam, North­

Holland,1971,pp. 311-407.

14. H. J. Landau and H. O. Pollak, "Prolate Spheroidal Wave

Functions, Fourier Analysis and Uncertainty - III: The Dimension

of Essentially Time- and Band-Limited Signals," Bell System

TechnicalJournal, 41, July 1962, pp. 1295-1336.

15. A. Capozzoli, C. Curcio, A. Liseno, and P. Vinetti, "Field

Sampling and Field Reconstruction: A New Perspective," Radio

Science, in press.

16. F. Gori and G. Guattari, "Shannon Number and Degrees of

Freedom of an Image," Opt. Commun., 7, 2, February 1973, pp.

163-165.

17. M. Hirose, S. Kurokawa, and K. Komiyama, "Compact Spheri­

cal Near-Field Measurement System for UWB Antennas," IEEE

International Symposium on Antennas and Propagation Digest,

Washington, DC,July 3-8, 2005,pp. 692-695.

18. E. Kume and S. Sakai, "Millimeter-Wave Radiation from a

Teflon Dielectric Probe and its Imaging Application," Meas. Sci.

Technol., 19, II, November 2008, pp. 1-6.

8. "A New, Non Perturbing System, for the Measurement of High

Frequency Electromagnetic Fields," Progetto di Rilevante Interesse

Nazionale, Research Program Funded by the Italian Ministry for

University and Research, April 2005, National coordinator: G.

D'Elia.

19. D. Serafin, 1. L. Lasserre, 1. C. Bolomey, G. Cottard, P.

Garreau, F. Lucas, and F. Therond, "Spherical Near-Field Facility

for Microwave Coupling Assessment in the 100 MHz-6 GHz Fre­

quency Range," IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compati­

bility, 40, 3,August 1998,pp. 225-234.

9. J. W. Odendaal and J. Joubert, "Using Hardware Gating to

Improve Antenna Gain Measurements in Compact Antenna

Range," Electronics Letters, 39, 22,October 1999,pp. 1894-1896.

20. O. Franza, N. Joachimowicz, and J. C. Bolomey, "SICS: A

Sensor Interaction Compensation Scheme for Microwave Imag­

ing," IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation, AP-50, 2,

February 2002,pp. 211-216. @)

10. A. Capozzoli, C. Curcio, G. D'Elia, and A. Liseno, "Singular

Value Optimization in Plane-Polar Near-Field Antenna Character ­

zation," IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, 52, 2, Apnl

2010, pp. 103-112.

�

IEEE Antennas and Propagation Magazine, Vol. 52, No.5, October 2010

Authorized licensed use limited to: Shanxi University. Downloaded on February 20,2025 at 02:40:51 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.

241