Ethics in Engineering

Thomas Taro Lennerfors

A Student!itteratur

r

The book is also available in Swedish: Etik for ingenjor,er, Studentlitteratur 2019.

COPYING PROHIBITED

This book is protected by the Swedish Copyright Act. Any copying is prohibited.

Anyone who violates t he Copyright Act may be prosecuted by a public

prosecutor and sentenced either to a fine or to imprisonment for up to 2 years

and may be liable to pay compensation to the author or to the rightsholder.

The contents of this e-book are an unaltered reproduction of those of the

print version of the book. Thee- book is a supplement to the print book in

accordance with chapter 1, parag ra ph 6 of the Swedish Freedom of the Press

Act.

Art. No 40007-SB

ISBN 978-91-44-16428-1

First ed ition

1:1

©The author and Studentlitteratur 2019

stude ntl itteratur.se

Studentlitteratur AB, Lund

Book design: Jesper Sjiistrand/Metamorf Design

Cover design: Jens Martin/Signalera

Cover illustration: Shutterstock.com

Contents

Preface 7

1 Introduction 9

The three domains of engineering practice 11

What is ethics? 13

The insufficiency of law 21

The structure of the book 22

2 Awareness 25

Working with technology 26

Working together with others 30

Ethics in your personal life 35

3 Responsibility

41

Freedom to - agent-specific aspects 43

Freedom from - context-specific aspects 46

Impact 47

The components of responsibility in practice 48

c,:

...

::,

<(

c,:

w

...

,-

Responsibilities of designers and users 50

Why take responsibility? 54

~

,-

z

w

0

::,

,-

"'

0

z

<(

4 Avoiding responsibility 57

We are determined 57

c,:

0

I

,-

::,

<(

w

...

I

0

No resources 58

Lack of time 60

Too many demands 60

Respect for authorities 61

Peer pressure 63

Division of labour 64

Rationalizations 65

5 Responsibilities of professional engineers 71

What is a profession? 71

The engineering profession 74

Responsibility of engineers and codes of ethics 77

Professional ethics in conflict with other values 81

6 Critical thinking 85

Emotions and reason 86

Six models for critical thinking 89

Discourse ethics 102

Casuistry 107

Strategic, biased, and reflective uses of the models 107

7 Consequentialist ethical theories 113

For whom? 115

What? 118

Rules and consequences 121

Total happiness or happiness for all? 121

Possibilities and risks 122

8 Duties and rights 129

Traditional deontological systems 129

Kantian duty ethics 133

Prima facie duties 136

cc

...

...

:,

<(

cc

w

...,

II-

z

Rights: patient-centred duty ethics 137

w

Cl

:,

,-

VI

Cl

z

<(

cc

0

I

...

:,

<(

w

..

I

I-

4

Con t en t s

9 Virtue ethics 743

Plato 143

Aristotle 146

Modern virtue ethics 149

Virtues or situations? 152

The Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path 154

1o Ethics of freedom 161

Nietzsche 162

Kierkegaard: the aesthetical and ethical way of life 165

Authenticity 766

Life and death 169

Libertarianism 170

Autonomy 170

11 Relational ethics 777

Ethics of care 179

Ethics in different relationships 183

Trust 186

12 Justice and fairness 793

Basic concepts of justice 794

Justice and its relation to other ethical claims 200

Unfairness and injustice 202

John Rawls 203

Robert Nozick 204

cc

:::,

,<(

cc

~

,,~

,-

z

13 Environmental ethics 21 1

A brief background to environmental ethics 212

~

0

:::,

Sustainable development and sustainability 214

C

The moral standing of animals and other things 217

,-

.,,

z

«

cc

0

I

Deep ecology 219

,:::,

«

Contents

5

14 Action and beyond 225

Ethical action following a judgement 225

Ethical action over time: a roadmap 227

Ideals and how to relate to them 228

The linear process becomes circular

229

15 Assignments and case studies 233

Awareness: assignment for chapters 1-2 233

The Kista construction accident: case study for chapters 3-5 233

GMO salmon: case study for chapter 6 236

Bribery: an exercise in casuistry (chapter 6) 236

Autonomous cars: case study for chapters 6-8 238

A robot to love: case study for chapters 9-11 240

Nuclear waste: case study for chapters 12-13 240

Interview study: assignment for chapters 1-13 242

"Just do it": assignment for chapter 14 243

Technical development project and thesis work 243

Notes 247

Image sources 253

References 255

Index of persons 261

Index of topics 263

"'::::,

I<(

"'

II~

1-

z

w

0

::::,

IV'>

Cl

z

<(

"'0

I

::::,

<(

w

I

I-

"

6

Content s

Preface

SINCE 2013, I HAVE BEEN TEACHING the course Engineering Ethics

cc

::,

....

<t

cc

w

>....

~

>-

z

w

0

::,

>-

"'

C

z

<t

at Uppsala University. Throughout the years, we have used a variety of

excerpts, chapters, and papers. In the autumn of 2017, I took the opportunity

to write this book, which is a kind of synthesis of the development of this

course. Therefore, I am indebted to many people for the contents of this

book, most of whom are not mentioned in these acknowledgements but in

the main text of the book.

An obvious source of inspiration has been Dan-Erik Andersson together

with whom I wrote the book Etik published in 2011. My colleagues Per Fors

and Peter Birch have been co-teaching the course, and I have learned a lot

discussing ethics with them. Peter has read and given useful comments

on the manuscript. Furthermore, I would like to thank the students of the

course, both those who have used and discussed other course literature

and the students in the spring of 2018 who read a draft version of this book.

Some of you really took the opportunity to contribute and I really appreciate

your commitment. I have also learned very much from and been truly

supported by Iordanis Kavathatzopoulos, and it is obvious that many basic

assumptions in the book and the synthetic model are heavily indebted to

Iordanis' thinking. Parts of this manuscript have been discussed at the TUR

ethics seminar on critical thinking and I thank all of the participants. Parts

have also been used in the PhD ethics courses (both basic and advanced

level) offered by the Faculty of Science and Technology. I have received very

good comments on the chapter on critical thinking models as well as other

good ideas from Anders Persson. And I also would like to thank Mikael

Laaksoharju who has taken the time to t ruly care about this book.

a:

0

:r:

....

::,

<t

w

:r:

....

"

UPPSALA, DECEMBER 2018

Thomas Taro Lennerfors

7

Chapter 1

Introduction

AN EP I SODE OF THE TV SERIES 24 is about a software engineer who is the

ac

::,

....

""w

c,:

>....

~

>-

z

w

0

::,

>v'l

0

z

""

c,:

0

I

....

::,

""w

I

>-

"

only one able to program a bomb that some terrorists want to detonate in

the middle of a large city. They kidnap him on his way to work and they try

to persuade him to do what they want. He refuses. The terrorists threaten

him and push his head underwater, but he resists. Not until one of the

terrorists takes out an electric drill and threatens to use it on the engineer

does he yield and start programming the bomb. This brief, macabre

episode shows that the engineer was valuable to the terrorists since he had

knowledge - unique knowledge - about a particular technology. He didn't

want to use his knowledge for evil purposes but was forced to comply. Did

he do the right thing? Was he responsible for the consequences when the

bomb detonated?

Let us now turn to another example a long time ago in a galaxy far, far

away. If you have seen Star Wars IV A New Hope you probably remember

that the rebels could destroy the Death Star by dropping a bomb into a

duct leading all the way into the very core of the construction. And maybe

you, like engineers and others, wondered how one could design something

that senseless. If the evil imperial forces had the technical knowledge to

construct such a marvellously horrible death machine, how could they

have made such an error? We get the answer in the 2016 movie Rogue One,

where Galen Erso, an engineer forced to work for the Empire, designs

9

the Death Star with this flaw in order for the rebels to be able to destroy

it. He engaged in an act of insubordination. This is clearly an example

of ethics in engineering. Could the engineer have done otherwise? One

alternative would be to raise his voice against building the Death Star, but

most likely the Emperor, Darth Vader, and the others would have remained

unconvinced, and the consequences for the engineer would have been

fatal. For long, Galen Erso tried to avoid the imperial forces, hiding on

a desolate planet, but when he was apprehended and forced to carry out

the completion of the Death Star, he had no reasonable chance to quit his

job. The Empire is not just something you quit. Further, Galen could have

remained loyal to the Empire by designing the best Death Star possible,

truly following orders and pleasing his bosses, but that would have been

against his principles. So, was his choice correct?

cc

::,

....

s(

cc

....,

>-

>...,

>z

....,

0

::,

>-

Vl

0

z

<(

a:

0

I

...

::,

<(

....,

I

Darth Vader.

10

Chapter 1 Introduct ion

>-

"

These are two extreme examples of ethics in engineering. But also, away

from the extreme example of fictive terrorists and now, on our planet,

engineers and others who are developing, implementing, maintaining,

and using technology face ethical issues.

The three domains of engineering practice

As an engineer, you will work with technology, which is the first domain of

engineering practice. Technology - whether defined as artefacts, the skills

and knowledge to produce such artefacts, or as more intricately linked

technological systems - shapes our society by shaping our perceptions

and actions (see further chapter 2). Technology thus has an impact on

humans and nature.

BUILDING BRIDGES

The movie Dream Big features Avery Bang. When she was an engineering student,

she did not really know what to do with her life, but then she studied abroad in

Fiji. There, she rea lized how simple bridges could t ransform people's lives, and

t herefore she decided to dedicate her life to bui lding bridges. She is now the

president and CEO of Bridges to Prosperity, which contributes to community

development by providing footbridges over impassable rivers.

THE SLOPPY INSPECTOR

cc

...

::,

<(

0::

w

r-

...

~

r-

z

w

An eng ineer was hired by a construction company to inspect a facade on a

bui lding in Manhattan. In 2011, he filed a report stating t hat the facade was safe.

Four years later a part of the facade fell down and killed an infant. The engineer

admitted t hat he never inspected the site and t hat the report was completely fake.1

--------------------------■

0

::,

r-

"'

0

z

<(

0::

0

I

...

::,

<(

As a developer of tech nology, you could be the very mind behind the

technology, or the one improving and changing it. Your decisions affect

how people relate to the technology and thus you shape people's perceptions

and actions quite directly. You might also be the one who maintains the

technology, controlling it, inspecting it, and adapting it to the present

Chapter 1 Introd uction

11

needs. You could also be an implementer who decides which technologies

others should use. Examples of implementers are municipal buyers and

managers. Implementation may concern robotic process automation of

project management, robots in healthcare, the decision to adopt climate

change geoengineering, and so on. As both a professional and a private

individual, you are also a user of technology. You actively decide to use

a particular technology, such as a social media platform, how much you

want to use it and when. By using technology, you support it and indirectly

contribute to developing and spreading it.

All of these different roles have a different impact. While all people are

users of technology, engineers to a greater extent work with development,

implementation, and maintenance of technology. Engineers therefore

have a greater impact than other people when it comes to technology. If

engineers have such an impact on our perceptions and actions, how should

they use that power?

Given this power, a main idea in this book is that one ought to promote

ethical reflection about engineering practice. If more engineers were to

reflect upon their own impact and the positive and negative sides of the

technologies they develop, it is likely that they would develop technology

with a positive impact on humans and nature. But it is not easy to be a

reflecting engineer, particularly not when it comes to technology. In the

early 20th century, sociologist William Fielding Ogburn2 coined the

term cultural lag, which points out that societal reflection, thinking, and

discussion always lag behind technological innovations and changes.

Technology seems to outspeed ethics.

TWO-SIDED PRINTING

cc

...

:,

<(

3D printing has allowed engineers to create prototypes and products in a way

that used to be impossible. For example, there are already now people who have

managed to print semi-automatic guns. But. on the other hand, 3D printers may

also be used to print prosthetics.

cc

w

......

...z

-'

w

0

:,

...

v"I

0

z

<(

cc

0

...

I

:,

<(

w

I

...

G

12

Chapter 1 Int roduc tion

Apart from working with technology, engineers constantly work together

with others, which is the second domain of engineering practice. These

others can be stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, and managers.

Here, issues such as workplace relationships, fair compensation, bribery,

and the handling of sensitive information come up. A third area is ethics

in your personal life, since this often has an impact or is impacted by your

engineering practice. It may relate to you as a consumer or family member.

What do you do if your job has a negative impact on your private life, or

vice versa? The book aims to cover these three domains.

What is ethics?

0::

::,

><(

0::

w

>>~

>-

z

w

0

::,

>v,

0

z

<(

0::

0

I

>::,

<(

In general, ethics is about how one should live one's life, what is good, what

is the right way to act, and what one should do. And in that sense, ethics

is everywhere. Philosopher Claes Gustafsson argues that a basic human

activity is that we moralize, which means that we constantly evaluate

other people's actions from an ethical perspective: 3 "She shouldn't have

lied in this situation." "When you make a business deal with this company,

count the number of fingers you have left after shaking hands with their

representatives." "A robot can never be human." "That dude bought a sex

robot - yuck!"

But moralizing is not enough. It is rather automatic and at times you only

end up reproducing what others are saying and thinking. But how about

you? What do you think? Perhaps you rely on your gut feeling. But is the gut

feeling correct? Did people in former days not have a gut feeling that slavery

was okay? Or that women were not allowed to vote? Furthermore, you might

face ethical dilemmas in your life which you cannot just moralize about. For

example, should you try to study two different master programmes at the

same time to learn more, or should you instead take care of your relationships

with your family, your friends, and your partner? Should you doublecheck

all the calculations made by your colleague or do you trust her competence?

Should you accept the offer to work at a company developing weapons systems

or not? In these dilemmas, you do not moralize, nor make judgements about

a certain ethical issue, because the dilemma concerns you directly. The aim

of this book is to support you to develop the skills to make judgements and

Chapter 1 Int roduct ion

13

navigate through dilemmas within the three domains of engineering practice.

This is important for your future working life, so important that it is required

in the Swedish Higher Education Ordinance for all bachelor's, master's, and

3-year and 5-year engineering programmes. A key concept for this is critical

thinking (see chapter 6).

To learn how to think critically about ethics, it is important to think

with others. Therefore, the book will guide you through ethical theory as

it is discussed in various academic fields, as well as some more popular

contexts. At the universities, ethics is often seen as a part of philosophy,

where philosophers have discussed what concepts such as "good", "evil",

and "right" mean. These philosophers have also proposed normative ethical

theories - what principles should guide us in our lives. However, ethics is

also a central concern in other fields, such as anthropology, psychology,

and sociology. In these fields, ethics is often more descriptive. In other

words, they study how ethical decision-making works, how we respond

to various moral dilemmas, the norms, values, and cultures in different

groups, what role trust plays in building a functioning society, and so on.

In short, it studies what ethics is to people, how it functions. Ethics is also

studied by historians ofphilosophy, who try to understand Immanuel Kant,

Mary Wollstonecraft, Friedrich Nietzsche, Hannah Arendt, and other

philosophers in new ways. Furthermore, ethics is discussed by practitioners

and academics from various more practical fields, such as engineering. In

this book, you will think together with all of these sources of inspiration.

Ethics is messy

Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre described in the 1980s how the theoretical

discussion about ethics was fragmented and incomplete, and this also

applies to a great extent today. 4 He argued that when we talk about ethics,

both in practice and in academic debates, we use a wide range of concepts

that are all based on different theoretical foundations and which stem from

different historical contexts. Furthermore, sometimes we use the same

ethical concept to refer to different things. It is difficult to define ethical

concepts, and even if one manages to create a definition, it is not certain that

people will accept or use it. The ethical concepts are discursive constructs,

14

Chapter 1 Introduction

a:

::,

...

<(

a:

........w

_,

,_

z

w

0

::,

,_

V'>

C

z

<(

a:

0

...

:r:

::,

<(

w

:r:

l-

o

which means that they are created as words, concepts, and sentences in

our social practices (in groups, in societies, and so on). This means that

it is difficult to be sure of the exact meaning of an ethical concept. One

cannot merely look it up in a dictionary, on Wikipedia, or in the Stanford

Encyclopedia ofPhilosophy. In these sources, we get a particular view of how

the concept is understood, or should be understood, but not the "objectively

true" way, because there is (probably) none.

a:

::,

,_

<(

a:

w

,_

,_

,_

~

z

w

0

::,

,_

V,

0

:z

<(

a:

0

:r:

,_

::,

<r

w

:r:

,_

"

In his late work, philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed that it is not

easy to create precise definitions of a certain concept.5 He tried that in his

youth but gave up. For example, it is very difficult to define the essence of

the concept game, but all games share some characteristics of the concept,

such as chess, golf, badminton, soccer, and Monopoly. However, the same

features are not found in all of them. They have "family resemblances",

Wittgenstein said. The same goes for ethical concepts.

Take the example of the difference between ethics and morality. They

stem from the same word in two different languages - ancient Greek and

Latin. Seen from that light, they should mean the same thing. In everyday

speech, some use them to express the same thing, while others believe

that there is a difference. In philosophy, the concepts often mean different

things. However, academics distinguish between the concepts in different

ways, which leads to conceptual confusion, particularly since they are

sometimes not open to other ways oflooking upon the issue.

The most straightforward distinction, which may be found on

Wikipedia, is that morality represents the beliefs that people hold and how

they act within the sphere of doing good, right, and so on, while ethics

represents the systematic reflection about morality. So, ethics would be the

philosophy of morality or, in other words, moral philosophy.

This differs somewhat from existential philosophy (see chapter 10), where

morality represents the (often somewhat boring) norms of society. Ethics

for these existentialists concerns being true to yourself and not wasting

your life following the rules of others. As the Swedish band Broder Daniel

sings, "Why is it so we die just as copies/If it's so we're born originals."

There are other distinctions as well. Some say that ethics is the guidelines

provided by an external authority, such as codes of conduct or religious

principles, while morality is personal convictions and one's own principles

Chapter 1 Introd uct ion

15

about what is right and wrong. Another way of distinguishing between the

concepts is that morality is about what should or should not be done (for

example not to violate human rights), while ethics describes the process

of reaching a judgement about what to do. In this text, we use ethics and

morality synonymously, since there are more conceptual disadvantages

than advantages involved in distinguishing between the two.

So, how can we study this messy field? We could, on the one hand,

structure the chaos by providing clear definitions of concepts. This strategy

would probably still lead to not everyone accepting and using the concepts

in the way we intend. And if we have a strict definition and others use

another definition, it will limit our ability to communicate, which creates

frustration and conflict between us. On the other hand, and which is what

this book suggests, we could embrace the messiness, muddle through

ethics, and try to sketch a preliminary outline of how we generally use these

ethical concepts and how they relate to each other. In this way we can add

nuance to discussions, and we learn to think rather than slavishly follow

strict definitions. Additionally, it allows us to be flexible when new concepts

appear in the debate, which they will definitely do. This is also a way to use

the theories about ethics for our main purpose - to think critically.

In the next part, we make a first attempt to think critically about some

ethical concepts we face in our everyday lives.

Ethical concepts

We have already discussed the distinction between ethics and morality.

Another important concept sometimes used is norms. A norm is some kind

of rule of action that is normative - and normative means how we should

or ought to behave. If someone says that "it's not cricket" they mean that

the norms of fair play or decent behaviour are being broken. Norms specify

what is normal. Norms are not always good. Perhaps being heterosexual is

the norm if you are an engineer, and gay and lesbian engineers then have

to hide their sexuality to safeguard their careers.6 In engineering practice,

norms may also have a non-moral meaning, for example technical norms.

Rules are similar to norms, but in everyday speech they are not always as

embedded with value as norms. For example, there may be rules of soccer,

16

Chapter 1 Introduction

cc

::,

,_

<(

cc

w

,_

,_

,_

~

z

w

0

::,

IV'>

0

z

<(

cc

0

:r:

,_

::,

<(

w

:r:

l-

o

cc

::,

><(

cc

~

>-

z

u.,

0

::,

>-

"'

0

z

<(

cc

0

:r:

>-

::,

<(

u.,

:r:

><l>

which might not be related to ethics (but following them is an ethical

issue). Rules are frequently distinguished from principles, which are seen

as more directly stemming from some kind of ethical argumentation and

ethical values. Principles are also broader than rules. During the history of

ethics, there has been a lot of critique against rule-following. For example,

sociologist Zygmunt Bauman has argued that the Holocaust was not

based on evil but on rule-following. 7 Yes, perhaps there were genuinely

evil people around, but the main bulk of those carrying out the Holocaust

were people who just followed rules. And this is yet another argument for

the importance of critical thinking.

Another word related to ethics is values. One is often confronted by

questions about what one values in life, or which values one lives by. In many

companies, the "core values" of the company are described, for example

stating that the company should not only be profitable, but also care about

values such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) or sustainability.

Intrinsic or inherent value is often distinguished from extrinsic or

instrumental value - do we believe that something is valuable in itself

(intrinsic), or just as a means to something else (extrinsic/instrumental)?

For example, one might debate whether the environment has intrinsic or

instrumental value. If we want to preserve the environment for the sake

of human beings, then it has instrumental value. If we preserve it for its

own sake, we take it to have intrinsic value. There are also values that do

not relate to ethics, such as aesthetic values. You might think that a piece

of music is good, that it has aesthetic value, and that it has little to do with

ethics. We may also say that various business deals have economic value.

So, value is a broader concept than ethics.

Right is yet another word related to ethics. "She did the right thing" is

an expression that we often hear. The right thing may be linked to ethics

if it concerns the right choice in an ethical dilemma, but it may also be

disconnected from ethics if it concerns the right answer to a mathematical

problem. Sometimes one distinguishes between the right and the good,

where "the right" is more concerned with principles and "the good" with

outcomes. "The right" is more often linked to deontological, duty-based

theories (see chapter 8) while "the good" often is related to consequentialist

theories (see chapter 7). But sometimes we use them in other ways.

Chapter 1 Introd uct ion

17

r

Often we distinguish between the normative and the descriptive. The

descriptive is when we account for something as it is. It is more related to

facts. The normative, which is sometimes called prescriptive, concerns how

we want things to be. Others distinguish between prescriptive - something

that should be done - and proscriptive - something that should not be done

- which is somewhat similar to the distinction between maximalistic ethics

(reaching standards of ethical excellence) and minimalistic ethics (doing

only what is required of you).8 Returning to the distinction between the

descriptive and the normative, the 18th-century philosopher David Hume

has argued that there can never be normative conclusions stemming from

descriptive premises, something that is called the is/ought gap or Hume's

law.9 Imagine someone saying that human beings evolved as meat-eating

animals and therefore we should eat meat. Hume would say that although

it is a fact that human beings did evolve in this way, it does not follow that

we ought to eat meat. Rather, there is an implicit assumption that we ought

to do what we evolved to do. 10

Many ethical theories concern the normative - how we should live,

what we should do and so on, but theories may also be descriptions of how

we behave. Although Hume's law is sometimes called Hume's guillotine,

the distinction is not clear-cut. Remember the fact that many homosexual

engineers hide their sexuality at work. Within this descriptive statement,

there is also a more normative message - they should not have to do this.

Still, the distinction is useful for thinking about ethics.

DESCRIPTIVE AND NORMATIVE EGOISM

Psychological egoism is a descriptive theory saying that we are egoists - we think

about ourselves all the time. Ethical egoism is a normative theory (see chapter 7)

saying that we should be egoists.

a:

::,

.,,

I-

a:

w

....

I-

,_

~

z

w

Yet another concept is etiquette. While ethics is about "taking serious

things seriously", as philosopher Goran Collste11 writes in his Introduction

to Ethics, etiquette primarily concerns things that could be seen as less

serious than ethics. Sometimes we describe etiquette as manners. In Japan,

"manner mode" means silent mode on a mobile phone. Even though

18

Chapter 1 Introduction

c:,

::,

....

v"I

Q

.,,z

a:

0

I

1-

.,,

::,

w

I

,_

0

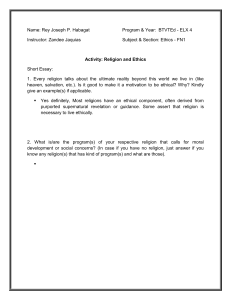

Image removed for copyright reasons.

Manner rules in

the Tokyo metro.

etiquette might seem irrelevant for ethics, our behaviour when it comes

to minor matters could raise awareness about larger issues. Look at the

Japanese manner rules in the figure above. If we realize that we cause harm

by being drunk and passed out on the train, litter, or open an umbrella so

that some people are exposed to water, we are likely better equipped to see

our impact in other, more important practices. So, the next time you hold

the door for someone, perhaps you learn something very deep.

Ethics as awareness, responsibility,

critical thinking, and action

a:

:::,

1-

<t

a:

w

II~

1-

z

w

Cl

::,

IV\

C

z

<t

a:

0

:r:

1-

:::,

<t

w

:r:

1,;,

In this book, a process is presented which sees ethics as consisting of four

steps: awareness, responsibility, critical thinking, and action.

Let us first discuss awareness. If we are not aware of ethical issues,

then it is of course difficult, if not impossible, for us to act ethically, to do

good. Therefore, a first step must be to become aware. This seems simple,

but it is not. We are often used to one way of seeing things. Ethical issues

may be hidden behind what Claes Gustafsson calls the wall of obviousness

- a psychological barrier limiting ou r perception of reality, 12 and more

specifically in this book, a barrier making us blind to ethical issues. This

wall is built by our expectations, and its bricks are our habits. Being able

to identify an issue as ethical is a first step. It is about making the practices

that you are part of an object of reflection, to become sensitized to ethics.

Chapter 1 Introduction

19

r

The wall of obviousness.

The second step is to make the ethical issue your own, in other words to

take responsibility for it. It is easy to say that this or that particular ethical

issue is not your concern, that somebody else should deal with it, that you

do not have the means to have an impact on it even if you tried. Certainly,

you do not have to carry all the burdens - some issues are the responsibility

of others to solve, but perhaps fewer than we regularly think. To make an

ethical issue your own, or to take responsibility, is thus the second step in

this ethical framework. But what is responsibility? And what are our usual

ways of avoiding it?

The third step of the ethical process is critical thinking. Critical thinking

does not mean to be "against something", to criticize, but to see an issue

from various perspectives, highlight the advantages and disadvantages,

the good and bad sides, and, based on this process, to reach a judgement

about the issue. Critical thinking is about thinking yourself, but is assisted

by thinking together with others. This does not mean that we can hide

behind others or behind ethical theories. Critical th inking demands that

ethics is more than political correctness. Even if a lot of people, including

your friends and family, even the entire society, thinks that some practice

is ethically good, critical thinking still requires us to think and reach our

own judgement, even though it is much easier to go with the flow.

20

Chapter 1 Introd uction

c,:

::,

I<(

c,:

w

II~

1-

z

w

C

=>

I-

v'>

C,

z

<(

""

0

I

I-

=>

<(

w

I

1(1

The fourth step is action. It is not sufficient to just judge what is right in a

particular situation, and then do something else. For example, perhaps you

know that you should not go by car to work because of the environmental

impact, but you do it anyway. Ethics can never be about only thought and

reflection. Ethics is intrinsically linked to action.

The various steps in this model will be explained in the book. But before

that, we need to turn to an argument that says that ethics is not needed at all.

The insufficiency of law

~

>-

z

~

0

::,

>-

"'

C

z

<l'.

C£'.

0

I

>-

::,

<l'.

UJ

I

0

Think about all the laws that exist in the world, which allegedly are

based on what we believe to be ethically correct. For example, since we

value that everyone, irrespective of gender, ethnicity, religion, and so on

is treated the same way and has the same opportunities, there are laws

against discrimination. So why is ethics needed if such frameworks are

already in place? Why do we have to think about ethics rather than just

following the law?

First of all, we can never be sure that the rules, laws, and frameworks are

ethically correct. Throughout history, we have reformed law because our

values changed, or when the power structure of society made it possible for

us to change it. For example, voting rights were for a long time restricted

to men and slavery was permitted. While we might think that we are at the

"end ofhistory", the final state in which all laws are just and right, we should

probably think that some laws still need to be reformed. There might thus be

a potential conflict between ethics and law. Some claim that anti-piracy laws

are immoral since they just protect the interests of powerful corporations.

Others claim that a strong right to ownership (which is protected by law) is

immoral since it makes society unequal. This discrepancy between ethics

and law is one reason why following the law is simply not enough. What is

interesting, however, is that we often learn about morality through what is

legal and illegal. In other words, we might learn to think that something is

unethical because it is illegal.

Second, and in line with the preceding argument, it is important to

remember that laws and principles are socially and politically constructed,

which basically means that they seldom represent a potential objective

Chapter 1 Int roduction

21

truth, but rather emerge from social processes. The laws allowing slavery

were not created by the slaves, but by others. This might seem to open up

to too much arbitrariness, but it also gives us the insight that laws can

be changed by social processes. If there are laws we do not find ethically

correct, it is possible to change them.

Third, it is not entirely easy to follow a law. It is well-known that all laws

need to be interpreted to work in practice. There is also a need for judgments

about how the law should be applied in each particular case, which is the

reason why there are courts. In each case we need to think about what the

law means and how it should be applied. There is thus a need for a reflective,

critical attitude rather than one of pure submission. This is what we try to

promote by means of the ethical process.

Fourth, one needs to remember that not everyone always follows the

law. Perhaps you walk or cycle against a red light, which is illegal in many

countries. Imagine then what others might do.

The structure of the book

In chapter 2, awareness is discussed, and examples are provided from the

three domains of engineering practice: working with technology, working

together with others, and your private ethics. At the end of the chapter,

you will for the first time meet a case that you will follow throughout

the book: you are going to imagine that you are working at a company

which will develop a robot and think about the ethical issues you will face.

Chapters 3-5 concern responsibility. Chapter 3 is about the components of

cc

Responsibility

Chapters 3-5

::,

....

.,:

cc

w

....

_,

~

,-

z

w

Awareness

Chapter 2

0

::,

Critical thinking

Chapters 6-13

1v'I

0

2

.,:

cc

0

:r:

....

Action

Chapter 14

22

Chapter 1 Introduction

::,

.,:

w

:r:

The st ruct ure of the book.

I-

"

responsibility, what it means to be responsible, and when we can say that

we are responsible for something. Chapter 4 describes how we willingly or

unwillingly do not take responsibility. Chapter 5 concerns the particular

responsibilities that professional engineers have. Chapters 6-13 concern

critical thinking. In chapter 6, models of ethical judgment and decisionmaking are presented. The rest of the chapters concern thinking together

with others by studying ethical theory: consequentialism, duty ethics,

virtue ethics, ethics of freedom, relationships, justice, and environmental

ethics. All these theories are expected to contribute to the judgment and

decision-making model in order to create better and more reflective

decisions. Chapter 14 concerns action - the last step in the ethical process.

The book is concluded by a number of assignments and case studies.

STUDY QUESTIONS

1

2

3

What are the three domains of engineering practice?

4

What does it mean that ethics is messy?

In which academic fields is ethics studied and are there any

differences in how ethics is studied in these fields?

What does it mean that ethical concepts are discursive constructs

and how does that influence the meaning of ethical concepts?

What is the difference between ethics and morality? How do you use

the concepts?

5

6

7

:,

"'

...

<(

"'

w

......,>-

8

>-

z

w

0

:,

>v'1

9

0

z

<(

"'

0

...

I

:,

<(

w

Did the engineer in the TV series 24 who programmed the bomb do

the right thing?

Was Galen Erso from the movie Rogue One right not to

follow orders?

10

11

What are norms, rules, values, the right, the normative and

the descriptive?

What are the steps in the ethical process described in the chapter?

What do you think about that process?

How can we think critically by using ethical theory?

What are the differences and connections between ethics and law?

...

I

0

Chapter 1 Introduct ion

23

r

Chapter 2

Awareness

A FIR s T s TEP in the ethical process is to be aware of the ethical dimensions

of engineering practice. To do this, we need to go beyond the wall of

obviousness (see chapter 1), since we often speak of engineering practice as

being unrelated to ethics. The ethical aspects are fundamentally concerned

with impact. People and things, texts and images, shape our perceptions

regarding what is good and desirable, and they also shape our actions. The

impact may not be direct - often it is about many small things that change

us over time. It is important that you are aware of this impact that you are

subjected to. But you also have an impact on others through working with

a:

~

a:

:::

technology, working together with others, and in your private life. Through

your actions, you contribute to forming the perceptions and actions of

others. In this chapter, a number of examples are presented from the three

domains of engineering practice (technology, work together with others,

private life). The purpose of this wide range of examples is to increase

awareness and hopefully have an impact on the way you perceive the world.

w

:r:

~

G

25

THE STEREOTYPICAL ENGINEER

In media, the engineer is often depicted as a lone, male, creative genius. In the TV

series Prison Break, the construction engineer Michael Scofield tries to break out of

a prison with his brother. Scofield has idiosyncratic plans and an enormous sense of

detail. Even though this representation of engineers as "experts and lone wolves"

may be inspiring to some, it does not represent a general picture of how engineers

are and how they work. Instead, imagine all the collaborative engineering projects

where ideas are created in interaction between several individuals. How the media

portrays engineers generates images that have an impact on engineers and the

interest of younger generations to become engineers.1

Working with technology

As an engineer, you will develop, implement, or maintain technology. As in

the conclusion from our discussion about ethical concepts in chapter 1, there

is not one definition of technology which everybody agrees on. Technology

is often seen as material artefacts, in other words things (tools, machines,

housing, clothing, transportation, etc.) that have some function. For

example, the function of a knife is to cut. From a broader perspective,

technology is also the knowledge, processes, and skills necessary to develop

and use these material artefacts. French philosopher Jacques Ellul2 took

yet another step and saw technique as an instrumental worldview. He held

that technique constituted the rational methods and procedures aiming at

absolute efficiency. This worldview self-augments and spreads everywhere.

It becomes a milieu where human beings must live, and all must define

themselves in relation to it.

If we return to the basic definition, technology is seen simply as

a material artefact with a function. This has led many to conclude that

technology is value-neutral, in other words amoral (without relation to

ethics and morality). But some have argued that values are embedded

in technology. An example is Langdon Winner's3 discussion about the

overpasses over the road from New York to Long Island, designed by Robert

Moses in the 1930s. These overpasses were low, and the public buses were

too high to pass under them. This prevented the least well-off, including

minorities, from getting to Long Island Beach. Even though the historical

26

Chapter 2 Awareness

cc

::,

....

<(

cc

w

....

....

..,

....

z

w

Cl

::,

....

V'>

Cl

2

<(

cc

0

I

....

::,

<(

w

I

....

0

accuracy of the account is contested or even proven to be outright wrong

by later research, 4 one could conclude that it would have been possible to

design overpasses that affect society in this way. And even after the death

of the designer, the overpasses would continue to embody the designer's

values. The material artefacts have thus become the bearers of values and

cannot be said to be value-neutral.

Philosopher Slavoj Zizek5 describes how values are even built into

something as banal as toilets. In a German toilet, the outlet is in the front,

and in the back the excrement is laid out for us to inspect with our senses,

perhaps to see traces of illnesses. In a French toilet, the hole is at the back in

order to get rid of the excrement as quickly as possible when flushing. The

American (Anglo-Saxon) toilet is a synthesis: the excrement floats in it, but

not to be inspected. We could add the Japanese modern toilets, washlet, that

take care of our excrement in a high-tech manner. Zizek states that none of

these toilets may be accounted for in purely functional and rational terms.

Rather, each of the toilets mirrors an ideological perception, a normative

view, about how we should relate to our excrement. Also according to Zizek,

technology is not only about function but also concerns values.

More specifically one could say that technology shapes our perceptions

and actions. 6

w

:r:

~

Functional or ideological toilet?

Chapter 2 Awareness

27

Technology shapes perception

What is meant by technology shaping perception is that through technology,

we start to view things differently - we even start to think differently.

Technology shapes what we perceive through amplification and reduction.

It amplifies some aspects of reality and reduces others. By doing so, it shapes

what we see as "real" and "important". These structures are intertwined,

since the amplification of one dimension leads to the reduction of others.

German philosopher Martin Heidegger7 argued that technology in its

essence brings-forth, it reveals. This is captured in the saying: "if all you have

is a hammer, then everything starts to look like a nail." One of Heidegger's

examples concerns a river. Heidegger said that modern energy technology

brings forth this river as an energy deposit, rather than as an ecosystem

that furthers animal and human life.

On a thermometer you can read the temperature - a number that

amplifies one aspect of the local surroundings. We make decisions based

on this number (should I wear a jacket or not?), even though we know that

temperature in combination with other measures, for example humidity

and wind speed, gives a better notion of perceived heat or cold. TI1rough

media and communications technology, people far away can make ethical

demands on us. After a natural disaster, or during some conflicts, images of

suffering people and demands can reduce the moral distance, even though

the geographical distance is significant. Through such technologies, we get

closer to people across the globe, in both work and private life. But media

technologies also reduce parts of reality not covered by them.

Furthermore, consider the so-called trolley problem,8 in which a trolley

is moving at a high speed towards five workers who for some reason do

not notice it. The brakes have malfunctioned. You, a bystander, could

pull a lever redirecting the trolley onto another track, where there is just

one person standing (who also does not notice the trolley approaching).

Would you pull the lever? Many would, since they find it better that one

person dies than five. In another version of the trolley problem, a massive

guy stands on a walkway leading over the tracks. You stand behind him

and have the chance to push him so that he falls in front of the trolley.

Thereby, his massive body would stop the trolley and the five people on the

28

Chapter 2 Awareness

a:

::,

I<(

a:

w

I-

1-

...,

1-

z

w

0

~

Iv'\

0

z

<(

a:

0

I

I-

~

<(

w

I

l-

o

track would be saved. Many would not do this. In both cases we kill one

person instead of five, so what is really the difference? Some would say that

pushing a man is more active than pulling a lever, but is that really the case?

Perhaps the man is "innocent" compared to the people on the track who

have either chosen to be there or have a higher salary due to occupational

risks. Another way to explain the difference is linked to how technology

shapes perception. Technology, in this case the lever, amplifies the distance

between us and the death of a person, making it easier for us to carry out the

action. Similarly, it might not feel as bad to kill people with drones, rather

than killing them with your own hands.

Technology shapes action

cc

::,

...

cc

......

......,z

<(

w

0

...

::,

"'

0

z

...

...

<(

0

I

::,

<(

w

Technology also shapes action, since artefacts have embedded norms,

which sociologist Madeleine Akrich9 refers to as scripts. The way in which

we ought to use technology is sometimes embedded in its very material

structure. The technology tells us how to act. A speed bump, for example,

means "Lower your driving speed". A hotel key with a large cumbersome

weight attached means "Hand me back when you leave the hotel". A door

opener that only opens if you press the button for two seconds means "Use

me, but only if you need me so much that you can press the button for two

seconds" or "Don't accidentally open me". A potato peeler says that "If you

use me it will be faster to peel the potatoes, but you will waste more potato

than if you are skilful with a knife".

The physical characteristics of the technology invite some actions, while

others are inhibited. These dimensions are also intertwined, like the abovementioned amplification and reduction. You can use a disposable coffee cup

once, twice, perhaps for an entire day, but not for a very long time. Some

printer drivers are designed, by default, to print double-sided documents,

which nudges the user into saving paper, which is good for the environment.

There are ecological shower heads that increase water pressure, making

it seem as if we use more water than we do. Pavements and traffic islands

tell drivers "Don't come here". Everywhere in society, there is technology

containing and expressing norms.

...

I

(I

Chapter 2 Awarene ss

29

SMARTPHONES AND ETHICS

Compared to a few decades ago, we now have very close access to video

cameras. How does this cha nge t he way we behave? This availability makes us

able to collect evidence of morally good and bad actions and share this with

others. What are the ethical implications of this? Does the increased abi lity to

collect evidence lead us to collect evidence rather than to interfere directly?

And how does the consta nt surveillance affect our behaviour?10

THE IT SYSTEM

An IT system developed by a third party was implemented at a workplace. Users

were informed that the data stored in the system cou ld be used for commercial

purposes and that some user data was stored on servers in another country. To

be able to work effectively within the company, the users had to accept these

conditions. Implementing a technological system, such as an IT system, has an

impact on the users.

W hen you work with technology, you are contributing to how it sh apes

perceptions and actions. You therefore have an impact on the world and

need to think about what kind of impact you would like to have.

Working together with others

Engineering work is carried out together with others at a workplace, whether

it is in the private, public, or other sectors. If "working with technology"

relates to technology, "working together with others" relates to interpersonal

relations. It fundamentally concerns that you as an engineer work together

with other people who are or are perceived to be different from you. Perhaps

they are older, younger, more or less educated, more or less knowledgeable

of technology, or have more or less work experience. Perhaps they are from a

different part of the country, from a different country or a different culture.

Perhaps you work with them face-to-face or through communications

technology. The relationships are also complicated by the fact that you

sometimes come from different organizations with different agendas.

30

Chapter 2 Awareness

a::

...

......

...z

::,

<(

a::

w

~

w

0

::,

...

v'\

0

z

<(

a::

0

...

:r

::,

<(

w

...

:r

0

Customers

Many ethical issues arise in relation to customers, both internal (in your

organization) and external (your organization's custom ers). You as an

engineer might for example have more knowledge about the technology you

sell than your customers. Are you obliged to be entirely open for example

about weaknesses in the technology? Moreover, perhaps the customer

does not really need the product you are offering. Not seldom, advanced

technology is installed in developing countries, where it is used for a few years

and then remains unused due to a lack of resources and knowledge. Should

you, as an engineer, give the customer what she n eeds or what she wants?

THE LYING ENGI NEER

Genera l Motors was criticized for knowing that the ignition system in some of

their cars was dangerous, but sti ll did not hing to solve t he problem. Suddenly

the engine could switch off, which disabled airbags, power steering, and braking.

A person was killed because of this problem, and the case was t ried in cou rt. The

chief engineer announced that he did not contribute t o the error. The prosecutor

argued that he lied and said that there is a cu lture of cover-up at General Motors.

The engineer is still employed by the company.11

------------------------■

HYPERNORMS AND MICRO NORMS

;....

<t

One ca n distinguish between the norms that are agreed by a sma ller community

(for example a family, a group, or a company) and the norms that are more

generally accepted. The former are ca lled micro norms and the latter hypernorms.

It is possible t hat micro norms - that it is acceptab le to lie to customers - deviate

from hypernorms - t hat it is unethical to lie. But if such ethically problemat ic

micro norms are exposed in public, an ethical scandal mig ht arise .

cc

,_

....

,_

~

z

UJ

<Cl

::,

,_

"'

C

z

<t

cc

0

I

,_

::,

<t

UJ

I

,_

G

Co-workers in your organization

Ethical issues also arise between co-workers. Perhaps you might experience

that someone is harassed, and need to t hink about what you should do and

whether you should interfere or let the harassed person defend herself. You

might also experience degrading ways of talking about foreigners, women,

Chapt er 2 Awareness

31

and others, and need to think about whether you have an obligation to

change the workplace culture.

Issues of fairness, for example how much people have contributed to a

certain project, will arise. It might be difficult to assess who has contributed

to some successful business deal as well as who and how many people have

contributed to some wrongdoing. Another issue related to fairness is equal

pay - it is not uncommon that two people who do exactly the same job have

different salaries due to some irrelevant factor. How can you handle that?

Perhaps you realize that your work hours are not sufficient for the work

you are expected to do or that you never work full-time but still cash out

a full-time salary. In the knowledge-based workplaces of today, it is not

as easy for managers to control the employees' work, and this poses new

ethical demands on employees and managers.

Suppliers

Suppliers want to have a good relationship with you and naturally want

you to continue being their customer. Sometimes they will give you a well-

meant gift and other times perhaps a bribe. It is not entirely clear where the

line between an acceptable gift, perhaps a keyring with the supplier's logo,

and a bribe, perhaps a briefcase full of cash, is to be found.

Perhaps a supplier has come up with an innovative idea to solve a certain

engineering problem that you face, but you already have a long-standing

relationship with another supplier. You might feel the urge to tell your

current supplier about the innovative idea, but you know that this would

not be ethically correct.

Yet another issue related to suppliers is that you have to be a competent

buyer of the services your suppliers are offering, in other words that you in

some way live up to the expertise you are expected to possess.

cc

::,

1-

<t:

cc

w

,I~

,-

z

w

0

::,

,-

Competitors

v'\

0

z

<t:

In many technology-based industries people know each other. Perhaps you

have a friend who works for a competing company. It is not unlikely that

you and your friend talk about various job-related matters, but of course

32

Chapter 2 Awareness

cc

0

:r:

1-

::,

<t:

w

:r:

l-

o

r

you try to avoid leaking information or asking for sensitive information.

But in some industries, information tends to spread. This sharing of

information, which in a way is similar to cartel-like collaboration, leads

to increased short-term profitability for the company winning the bid but

is illegal under anti-trust regulations. In some countries, it is forbidden to

meet with competitors informally. Your work can thus have a negative effect

on your personal relations.

Codes of conduct

When you work in an organization you have to follow written or unwritten

codes of conduct. When you are employed, perhaps you need to sign a

statement saying that you have read and understood the rules. But the code

might be impossible to follow, for example if your direct supervisor tells

you to do something that is not allowed by the code. And sometimes your

colleagues might talk about the code as some nonsense invented by head

office - those who know nothing about how to do business. You might

also reflect upon which kinds of deviations from the code are acceptable

and when you should report them. Do you have a responsibility that your

co-workers follow the code or is it up to each individual?

Management

a:

::,

....

<t:

a:

........

....z

~

w

0

::,

....

V,

0

z

<t:

If you become a manager, you have more impact on others, and with this,

responsibility follows. Your job might be to motivate your co-workers, but

at the same time you cannot make promises you are unable to fulfil. How

do you make sure that your co-workers do not waste time and energy on

irrelevant things? You also might reflect upon how you could control that

they act according to codes of conduct. You know that one alternative

is trust and another one is control. The technological development has

ment that the means of controlling others are more developed today

than in the past.

a::

0

I

....

::,

<t:

w

....

I

"

Chapter 2 Awareness

33

As a student

Even as a student, there are ethical dilemmas related to working together

with others. You might wonder whether you should just focus on yourself

or help others achieve their goals. Do you have particular responsibilities if

you are very knowledgeable? This dilemma is common enough to be sung

about in a Swedish children's song:

You who are so good at maths will you explain to me

who is not so clever?

Or do you use your hand to cover so that nobody will see

how far you have come in your book?12

Imagine a co-student who is generally committed to her studies but who has

some personal issues and therefore cannot finish an assignment on time.

You want to help this person although university policy forbids you to do

so. Or imagine that you find out that this person bought an essay online.

Do you report this or is it unethical to be a "snitch"?

Most have experienced the problem of having a "free-rider" in the

group, but how do we deal with it? And how do you assess how much

each student has contributed to a group project if you as a student need to

recommend individual grades for your group report? How do we measure

such contributions?

In the classroom, particularly in today's society where traditional

lecturing has lost its status, it is important that students contribute to the

teaching. Being a good student, you are of course contributing to the class,

but are you also obliged to help other students contribute by involving them,

asking them questions, and asking them to tell about their experiences?

What if someone talks too much in class, taking time from others? This

does not seem fair either.

a:

::::,

....

<(

a:

....

I~

1-

z

w

0

::::,

I-

v>

C

z

<(

a:

0

I

....

::::,

<(

w

I

I-

Q

34

Chapter 2 Awareness

Ethics in your personal life

Ethical issues are also present in various parts of your private life.

Consumption

When you buy food, there is an abundance of choices you can make and

many are related to ethics. One example is ethical meat, which is produced

from animals that are raised with care at all stages of their lives. But still

you feel that meat cannot be ethical, because animals are raised for the

specific purpose of slaughter. With technological advances, artificial meat

that grows almost like a plant is being developed. Is this ethical? Does this

not nurture dreams and visions about eating "real meat"?

As a consumer, you often need to choose between a more expensive,

environmentally friendly product and a cheaper, less environmentally

friendly product. It is an ethical choice whether to buy one or the other.

By choosing, you make an impact on the world. By drinking a can of soda,

~

>-

z

u.,

0

;:,

>-

"'

0

z

«

a::

0

:r:

>-

::,

«

u.,

:r:

~

What product is the most ethical?

Chapter 2 Awareness

35

perhaps you support a beverage company with huge pay differences between

the CEO and the average worker. When you buy a computer or a mobile

phone, perhaps you support harsh working conditions in mines and corrupt

governments that benefit from the income from these valuable minerals.

In today's capitalist society, we talk a lot about the power of consumers

and that we should "vote with our dollars". An example of this increased

consumer power is the change of the slogan for the Swedish candy Ahlgren's

Cars from "The most sold car in Sweden" to "The most bought car in

Sweden", which represents a shift from a production focus (cars are sold by

producers) to a consumption focus (cars are bought by consumers).

Perhaps the capitalist system shapes us to think first and foremost as

consumers in various aspects of life. When we travel we consume places,

rather than relating to the local inhabitants. And maybe you are a consumer

of education, rather than a student.

The choices you make as a consumer might affect the other domains of

engineering practice. For example, perhaps you only buy vegan food for the

participants of a working lunch. Or you lobby for your company to only

buy Fairtrade coffee. Or the fact that your organization supports charities

makes you do the same as a private individual.

Family matters

In family life, perhaps in a relationship with a partner, there are constant

negotiations about values. One example may concern honesty and

faithfulness. Can one have secrets in a relationship and what kind of secrets?

How should one raise one's children? Should one influence their values or

let them be fully free to develop their own? Discussions about fairness often

come up in the family context. Children exclaim "this is not fair!" regarding

what time they have to come home, what time they have to go to bed, or how

much candy they are allowed to eat. A commercial from a Swedish candy

company shows a grown-up man sitting on a train, in a suit. He opens his

briefcase, where he has a bag of candies and he takes a few pieces. A child

sees him and asks her mother "What day is it today?" Children in Sweden

usually get candy on Saturdays. The commercial's slogan: being a grown-up

has its advantages.

36

Chapter 2 Awareness

...""

....,

""

.......

::,

<(

....z

~

w

0

....::,

v'>

0

z

<(

cc

0

...

I

::,

<(

w

....

I

"

The ethics we learn in a family context can be transferred to our

workplaces. For example, we can learn about interesting practices from school

that may be applicable to the workplace. Likewise, there is a transfer from

the workplace to home. We can teach our children how one behaves at work

and which values work life is based on. Some even use methodologies from

the workplace, such as project management tools, to manage their family life.

On the street

When walking on the street, you have perhaps met people who ask you

for change. Should you help them, or should someone else take care of

them? Or should we as a society not take care of them at all? A retired

school teacher saw that a Roma family was living in a car. He saw that the

daughter sat in the car, watching movies on the phone and eating candies.

He decided to intervene and let the family live in his house. Could you have

done the same thing?

When you want to cross the street at a pedestrian crossing without

traffic lights, in many countries the cars are forced by law to let you cross.

Perhaps without reflecting, you thank them by raising your hand or nodding.

However, when you cross the street and the light is green, you probably

seldom thank the drivers who let you cross. Thanking others, or treating

others with respect, at times seems to be quite ritualistic - and rituals may

also be seen as part of ethics, understood as the norms of society. Perhaps

this is related to etiquette?

Free time

QC

::,

....

<(

QC

w

....

....

-'

....

""

w

D

::,

>-

V\

D

:z

<(

QC

0

:r:

....

::,

<(

w

:r:

....,;,

In your free time, you might practise some sport, or be engaged in politics,

and so on. Let us take sports as an example. Imagine a football game where

you are the only player to see that a goal was scored by the opposing team - the

ball crossed the goal line, but the referee did not see it. Should you have told

the referee? In lower level badminton tournaments, the players are themselves

the line judges, which at times leads to conflicts. In higher level competitions,

there are line judges. They are not supposed to be biased, but they might not

always rule correctly. You could even imagine that they are corrupt. To solve

Chapter 2 Awareness

37

the issue, hawk-eye technology has been introduced. Players can challenge the

calls by the human line judges and let the technology decide. But it happens

once in a while that the hawk-eye is wrong. Technology could be a way to

avoid ethical discussions, but what if it does not work as expected?

Popular culture

From our infancy, we read stories and sing songs, and some of these have a

moral message, for example "Itsy Bitsy Spider", which says something like:

"Keep fighting despite the fact that it might seem difficult and pointless". In

these songs and stories, we learn about heroes, villains, and how to behave.

There are ethical messages in movies, lyrics, literature, art, and so on. Ethics

is also expressed in various sayings. Even in our work life, we hear stories

about good and bad behaviour, about heroes and villains.

The purpose of this chapter was to show the ethical dimensions in the three

domains of engineering practice by means of examples. A way to increase

your awareness is to try to reflect upon things that you have previously not

reflected about. The things you are doing - what do they say about you? The

laws you follow - what is the ethics of them? The work that you are carrying

out - what is it about? The songs you are singing - what is their message?

Fostering awareness is a matter of practice. To increase awareness we must

tune in to the right wavelength, we must put on a pair of ethical glasses

through which we perceive the world. By using our imagination, we might

see beyond the wall of obviousness.

a:

::,

I-

«

a:

w

I-

I-

STUDY QUESTIONS

_,

1-

z

w

Ll

::,

Iv'\

3

4

Why is it important to be aware of ethical issues?

What does Ellul mean by technique?

Are Moses' overpasses unethical?

What are the lessons one may draw from Zizek's example of toilets?

38

Chapter 2 Awa re ness

1

2

Ll

z

«

a:

0

I

1-

::,

«

w

I

I-

"

s

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

a:

::,

,_

<(

a:

w

,_

,_

,_

~

z

w

0

::,

,_

V,

0

:z

<(

a:

0

:r:

,_

::,

<(

w

:r:

,_

..

20

What does it mean that technology shapes perception and action?

Give three examples.

How does technology affect your life? Give examples. Does

technology shape your perceptions and actions?

What is the essence of technology, according to Heidegger?

How do energy technology, thermometers, and the lever in the

trolley problem shape perception?

What is a script?

What ethical issues may arise in your relationships to customers,

co-workers, suppliers, and competitors?

What is a code of conduct and how can you relate to it?

In what way is your ethics affected by you becoming a manager?

Which ethical dilemmas might you face as a student?

How do you view your responsibility as a consumer?

Which ethical issues do you encounter in your family relationships?

If you engage in any leisurely activities, analyse the ethical rules

involved in these (for example in sports, music, or club activities).

Analyse the ethical message of some stories you read as a child.

Think about a movie or TV series you have seen recently - which

ethical values does it, or the various characters in it, reflect?

What is the moral message of these sayings?

Swedish author Vilhelm Moberg: "Take care of your life!

Because now it's your time on earth."

Mahatma Gandhi: "'An eye for an eye' will make the whole

world blind."

Shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis: "The best way to succeed in

life is to always step on toes, other people's toes."

Benjamin Franklin: "When you're good towards others, you're

good towards yourself."

The Japanese saying: "Fall seven times, get up eight."

Ralph W. Sockman: "The test of courage comes when we are in the

minority. The test of tolerance comes when we are in the majority."

Write a brief reflection about some ethical issue you have

experienced recently (working with technology, working with

others, or as a private individual).

Chapter 2 Awareness

39

r

THE LIFE PARTNER AND YOU: AWARENESS IN PRACTICE

For some time you have been part of a design team in a mechatronics company. Like

any for- profit company, you want to expand into new areas, and during a meeting the

idea of developing humanoid care robots comes up. The employees in t he company are

really excited about the idea. Given your proprietary technology in mechatronics, you

are convinced that you cou ld develop a humanoid care robot that could revo lutionize

the market. At present, no such products exist.

You also discussed the possibility of combining this with a new form of artificial

intelligence, which has been developed by a division within your company. This could